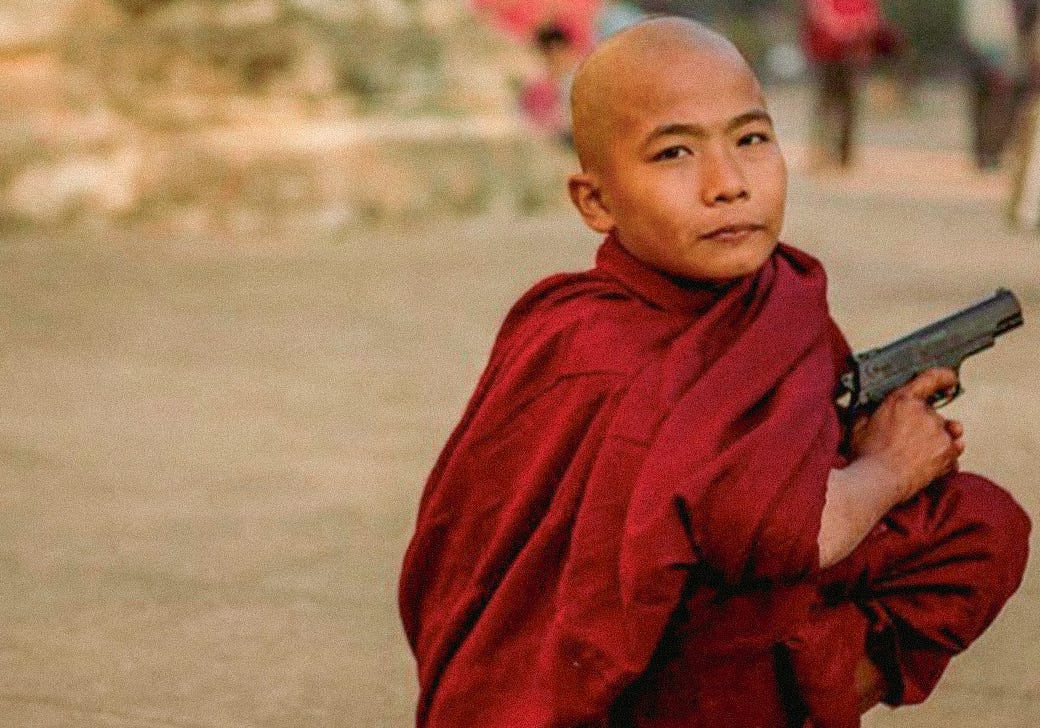

Buddhist Sleight of Hand

In which the author relfects on "The Seven Year Rule"

In the past week, I was twice recommended an article titled “The Seven Year Rule”. When I first read this two-minute article, I noted it as a possible starting point for reflection. After a second recommendation and read, I can’t resist.

The core idea is one you’ll no doubt be familiar with: how all the cells in our body change every seven years. As the author concedes, it’s not strictly true, but it’s true enough. He got it from the Dalai Lama, which should tell you what ideological job the factoid has been conscripted for. Buddhists do love to talk about impermanence and how everything’s always changing don’t they? Feeling joy? Wait a minute. Pain? It’ll be gone before you know it. All this too, shall pass. It’s a beautiful refrain (as far as it goes).

Grumpy curmudgeon that I am, it irritates me. I swear to God, one of these I’m going to become that loony popping all the balloons at a kid’s birthday party. But, I’m working on self-compassion so I’ll persist with my ravings.

What boils my bacon is the crass materialism of it all. This type of reductionism is the essence of Buddhism, and it wounds my fragile philosophical sensibility. Those of you who have practised Vipassana know what I’m talking about: any joy, suffering or pain you have is reduced to bodily sensation. Buddhism is hopelessly illiterate when it comes to emergence or systems thinking (or what is worse, I’m convinced it’s a wilful upaya-fuelled ideological ignorance). The symphony is reduced to its atomic notes and summarily dismissed. As if the whole were merely the sum of its parts. As if there were no relationships between the parts.

The Genius of Buddhism

Here’s the problem: it’s genius. It’s goddamn effective. A system cannot survive vivisection. You can destroy a system using divide and conquer. In fact, it’s probably the only way to do so. You can defuse a panic attack by wresting control of the breathing from the instinctual pattern. The best way to slay the dragon is, as Anne Lamott would say, bird by bird.

The thing about wrestling with the emergent system is that, at this level of analysis, it recreates itself. It’s too big for your will. And so, from a purely pragmatic stance, Buddhism is nothing short of genius.

You short-circuit this system of human psyche—which, as Heidegger noted, is extended across past, present and future—by eliminating two-thirds of it. Bye bye past. Bye bye future. The monster, already a fraction of its true self, is hobbled. Of course the system keeps trying to leak but anytime your mind strays towards past or future, you simply chop off those tentacles and keep it trapped in the here and now.

Now you take this temporally mutilated version of the system and you break it down further. You dissect the amputated remnants of your experience into its constituent parts. This emergent god of fury possessing you can be decomposed into sensations: clenched jaw, flaring nostrils, quickened breathing, clenched fists, blood coursing into your limbs. Sitting still amid this raging storm, you let it burn itself out. You rob it of its fuel: past, future, breath, action. You let it burn all this fuel up until, like any fire, it chokes and dies.

Congratulations, you have killed the beast.

But it’s still wrong

Now can we talk about how mistaken it is? It’s obvious why this reductionist religion has taken off so much in the West. The modern world is built on reductionism. Science is the great vivisectionist of systems. The advancement of knowledge has been built (and could only have been built) on a bird by bird basis. The complexity of systems are a nightmare to understand. But if you break them up into teeny tiny little parts—by isolating your variables using good laboratory conditions and experimental controls—you tune out all the noise and what you’re left with is that sweet, sweet signal. This was the low-hanging fruit which early science reaped by the bushel.

But once you step into waters where this becomes more challenging, for example, ecology, nutrition or psychology, the difficulties multiply exponentially. It turns out that parts of a system behave differently when stripped of their context. Kahneman’s work on human bias paints a picture of machines riddled with bad code. But this was lab coat kind of research. Gary Klein’s work on these same biases makes us look like well-adapted organisms. You can be wrong and still win (the meta-irony given our subject matter hasn’t eluded me).

The problem with the seven-year rule and with the Buddhist perspective in general is that, like good propaganda, its truth is partial. Its reductionism gives it power but it is built on a warped foundation (this is before we mention the more creative pragmatic additions like karma and reincarnation).

The seven-year rule is materially reductionist; it puts our identity into the quantity of atoms rather than the quality of relationship. You can have two collections of the same atoms: one, a puddle of water (with some interesting trace elements) and the other, your aunt Lucy. Same molecular soup; very different puddles. We are so far from being a quantity of atoms; we are a system.

Zooming further out, Buddhism is more broadly reductionist. As Heidegger noted, we are not creatures of the mere present; our minds are naturally extended across past, present and future. That’s why it’s so goddamn hard to keep your mind in the present. It’s unnatural. It’s like a river standing still.

Love is not merely a collection of sensations. Like the puddle and your aunt Lucy, the atoms of the experience don’t make the experience; the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Willoughby Britton’s research on adverse meditative experiences comes to mind here. The following is a first-hand account she collected from a woman struggling after a meditation retreat:

“‘I had two young children,’ another meditator said. ‘I couldn’t feel anything about them. I went through all the routines, you know: the bedtime routine, getting them ready and kissing them and all of that stuff, but there was no emotional connection. It was like I was dead.'”

Love, like anger and our other emotions, is not merely a cluster of sensations. They are the chemical messages coursing through the system that is human community. They are the blood of human society—the lifeforce moving throughout the organism. Emotions are the myelin sheath shooting signals throughout the system far beyond the body which first hosted them. They are deeply connected with action. You can short-circuit this system. But you don’t just remove emotions; you risk dissolving the ties that bind us. When the Buddhist magic deconstructed this mother’s love, her relationship with her kids was left a hollow routine.

Such are the powers of a half-truth. Were it in my power, above the entranceway to every meditation retreat, I would inscribe the eternal words of Ben Parker, “with great power comes great responsibility”. And on the cover page of every sutra, the words of Hamlet, “There are more things in Heaven and Earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

Yeah, sutric Buddhism is plenty life denying. You could say its about seeing that form is emptiness. It is. But the Heart Sutra adds: emptiness is form. Supposedly, arahants have a heart attack upon hearing that second bit.

What a beautiful article