So, last week of talking about systems and, appropriate to the acidic arc of life I’m sailing through at the moment, this week’s piece is a critique. Because it’s nice to have delved into a topic deeply, developed some sympathy for it, tested its lenses a bit and found some that you like and then to start hacking at its roots. And I wonder why I feel like I’m chasing my tail.

This article — entitled “Magical systems thinking” — comes from Works in Progress which is afaik Stripe’s publication. Not sure how I came across it but I’ve had their emails coming into my inbox for a while. Some are meh some gold. I’ll let you decide which this week’s reading was.

The first thing I learned from this article is that Systems Thinking is no small fish. I should have known this already perhaps given how much I’ve heard about the Club of Rome and how popular (Meadows’ first book) Limits to Growth was. But I still thought of it as this niche subcultural point of view. I guess I was wrong.

The second thing that jumped out was, of course, the spirited attack on Systems Thinking. It outlined a whole pile of Systems Thinking interventions governments have tried, which have utterly failed. It seems the complexity of systems outstrips our ability to effectively map them (those clouds in Meadows diagrams, it seems, were more dangerous than they seemed). This was a critique I’d been incubating myself what with the horrendous disparity between the pearl-clutching about population overload that accompanied Systems Thinking’s birth and the state of our current dilemma: demographic collapse > overpopulation.

But the real thing that grasped me from this article and why I wanted to share it, was not the negative corrosive work of critique that must be done, but the positive proposition that we can take away.

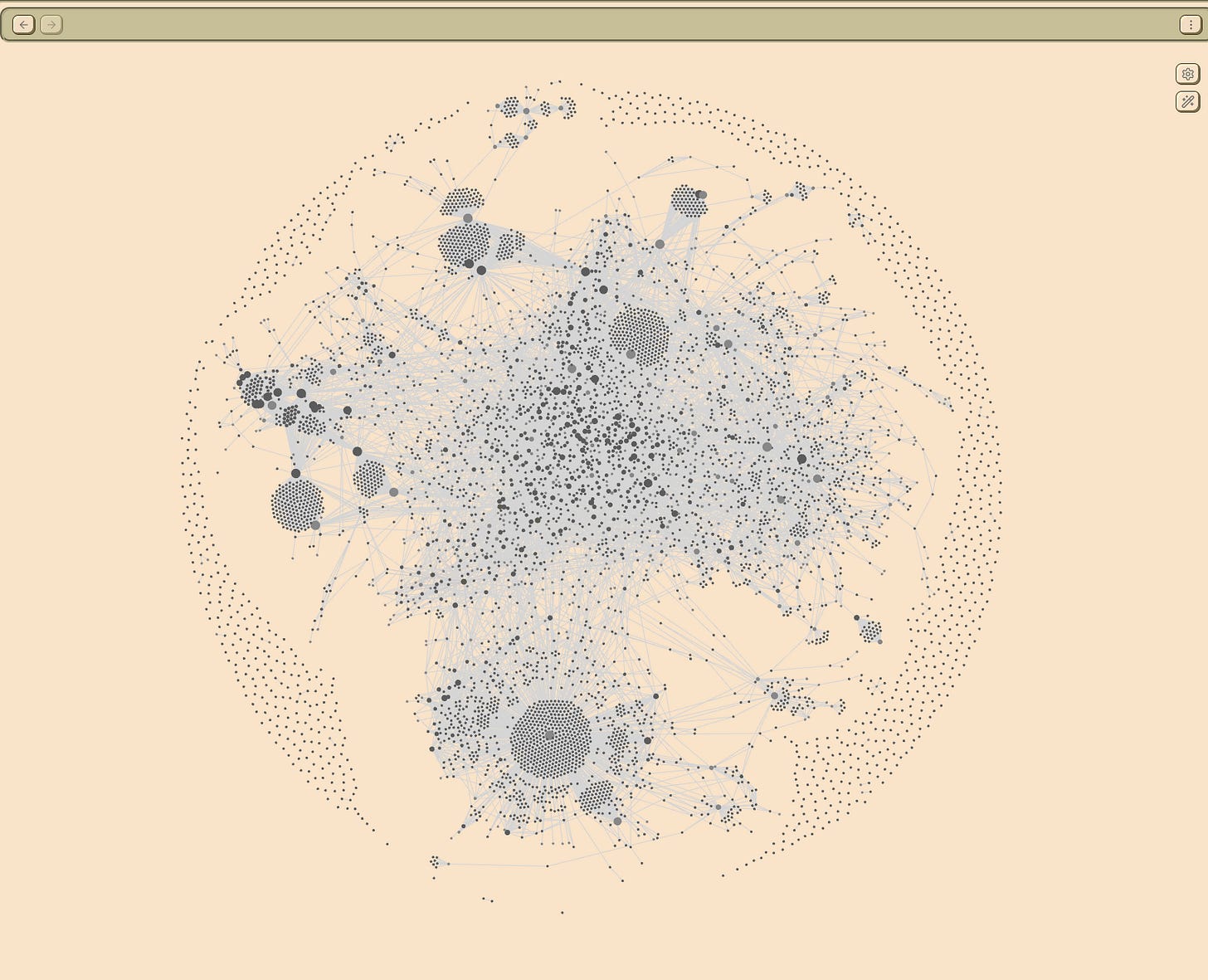

The takeaway for me was this: start small. Don’t go messing with complex systems. Start over. Start small. Build a system that works then add to it. It’s such a simple realisation, but as I write this in my Obsidian vault, where I have attempted to give birth to many complex emergent systems, I am aware that I write in a graveyard of big systems ambition. The past year I’ve been content to work in the ashes. But I grow more inspired by the idea of starting something simple and small that works. Then I’ll build upon that.

As I begin to work on the Jungian Masters here in Limerick, I am contemplating what shape my scholarly system will take. I’m nervous about having a run at my Zettelkasten system again, but I’m scared by the ghosts of notetaking systems past — the cities of thought whose empty ruins I still sometimes wander through, sad at the dreams that could have been. Why, in the 21st century, does it feel like there are so many basic things still needing to be worked out? There’s so much talk of second brains and second minds. The veterans among us know it for the frothy sales pitch it is. Or, perhaps more charitably, it is merely the enthusiastic proselytising of the starry-eyed novices. We all fell on our knees before the grandeur of Nikolas Luhmann’s Zettelkasten. But we were bowing down before a complex system that had decades to grow into what it was. We suffered from the same audacity as the Systems Thinkers and their complex diagrams (which ultimately proved to be all-too-simple): how to start humbly? How to start simply? With Gall’s Law:

“A complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from a simple system that worked. A complex system designed from scratch never works and cannot be patched up to make it work. You have to start over with a working simple system.”

A few notable quotes from the article:

“our successes, when they do come, are invariably the result of starting small. As the systems we have built slip further beyond our collective control, it is these simple working systems that offer us the best path back.”

“With the failure of his World Model, Forrester had fallen into the same trap as his MIT students. Systems analysis works best under specific conditions: when the system is static; when you can dismantle and examine it closely; when it involves few moving parts rather than many; and when you can iterate fixes through multiple attempts.”

“Starting with a working simple system and evolving from there is how we went from the water wheel in Godalming to the modern electric grid. It is how we went from a hunk of germanium, gold foil, and hand-soldered wires in 1947 to transistors being etched onto silicon wafers in their trillions today.”

“Le Chatelier’s Principle [the idea that the system always kicks back] provided an answer: systems should not be thought of as benign entities that will faithfully carry out their creators’ intentions. Rather, over time, they come to oppose their own proper functioning.”

“The long-term promise of a small working system is that over time it can supplant the old, broken one and produce results on a larger scale.”

“As systems become more complex, they become more chaotic, not less. The best solution remains humility, and a simple system that works.”

In the end, this is what I’m taking away from this flirtation with systems thinking the past couple of months.

Systems are gorgeous. They are miraculous. The idea that a whole can be greater than the sum of its parts is dazzling, especially when it stretches beyond the domain of life into the abstract domain of culture, where our relationships with each other become alive in a way that is not quite human. The miracle of emergence is overwhelming.

Yet, it is more complex than we can hope to architect. Is this not the reason the socialist Communist states failed across the world while the free market bloomed? So, to be candid, my takeaway is Voltaire’s “il faut cultiver notre jardin” (we must cultivate our garden). But this isn’t the fatalist capitulation it might seem — the collapse into “desperate narcissism” that some leftist commentators might see. Instead, this act of gardening is the humble beginnings of a new cosmos.

"Elements and Relations" by Martin Zwick is my only properly "systems" book, but it's wonderful. Highly recommend.

Thanks for this wonderful series!