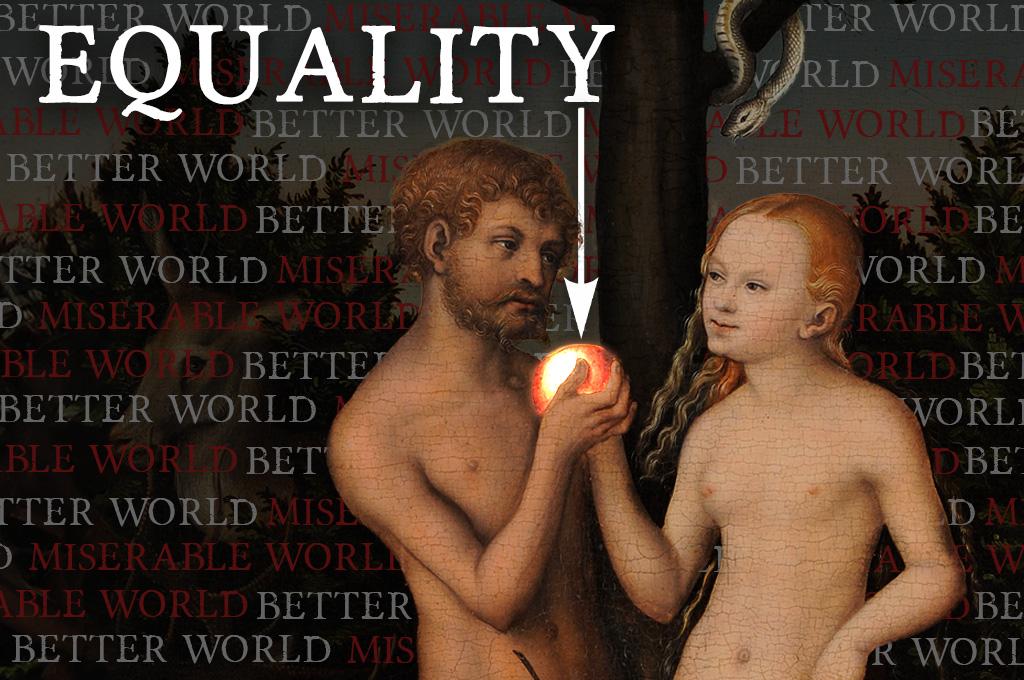

There’s an old saying that ignorance is bliss. When it comes down to it this is the lingering question of the Garden of Eden and it is the question of modernity; We can frame it like this:

Would you rather be happier or live in a better world?

Would you rather the ignorant bliss of Eden or would you like your eyes opened to knowledge of good and evil though this knowledge breaks your heart?

Our modern faith assumes that these two go together but history and practical experience has taught us otherwise. The fruit of the great modern project of liberty, equality and democracy was not what we expected. Like Adam and Eve we expected a sweet improvement on our former state. Instead we have found the fruit bitter and now we must toil the hard earth outside the Eden of our ignorance.

We expected our material, technological and social progress to bring with it progress in happiness and well-being. This has not been the case.

From the American War of Independence and the French Revolution to the Civil Rights Movement and the Arab Spring, the doctrine of equality has brought us closer to the image of Paradise but paradoxically it has left us feeling more and more like Hell.

The terrible beauty of modernity has made us more equal but also more hateful, more depressed and more envious. We keep telling ourselves that if only this were improved or that was improved then utopia would ensue. But few of us believe in this utopian horizon anymore. Disoriented we have collapsed into a rudderless crisis where we wholeheartedly embrace the crisis of the day and just as readily move on to the next one tomorrow as our algorithm and feeds demand. The cause of the day drives the cause of yesterday from our mind; what remains is the feeling of outrage and anger at the state of the world.

In this instalment we are going to look at this mixed brew of equality and its connection to the previous instalments’s subject ressentiment. We’ll look at the early days of America and how social media has turbocharged our productive discontent in the 21st century.

Democracy in America

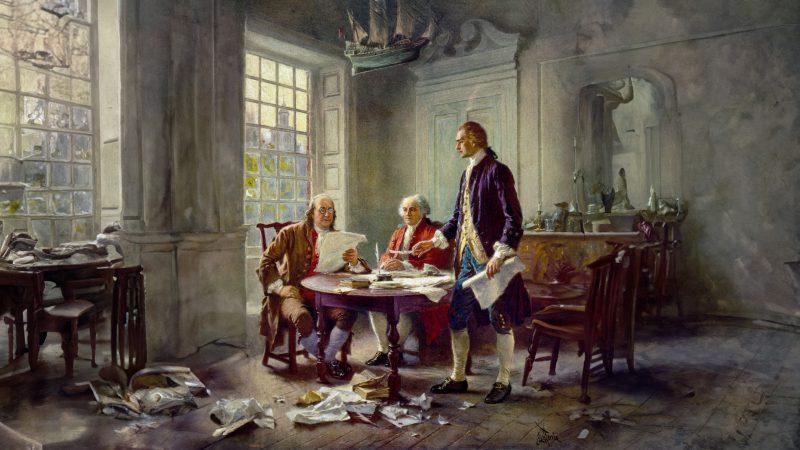

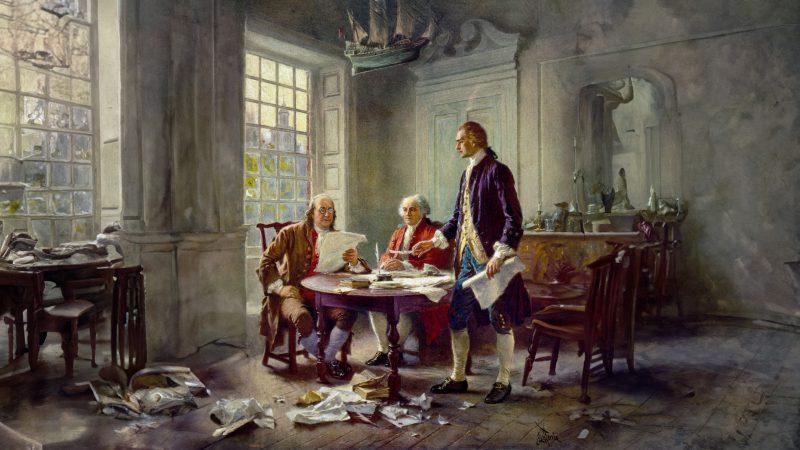

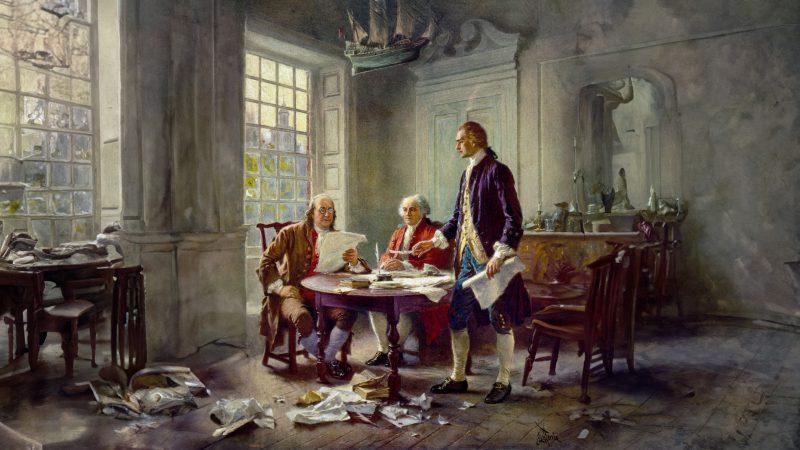

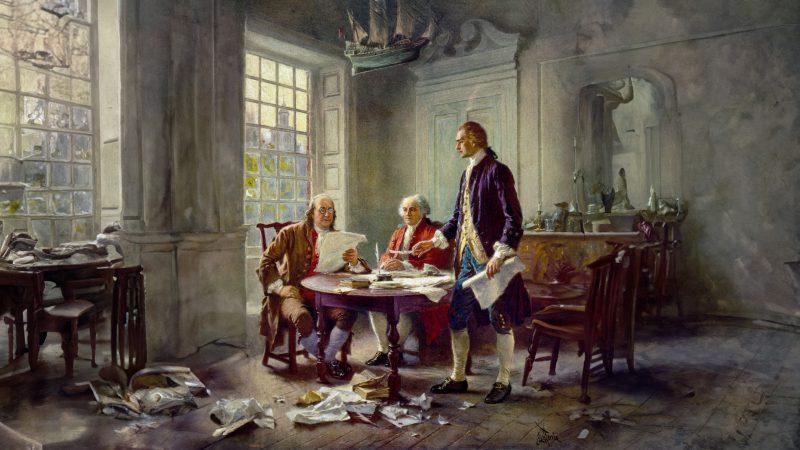

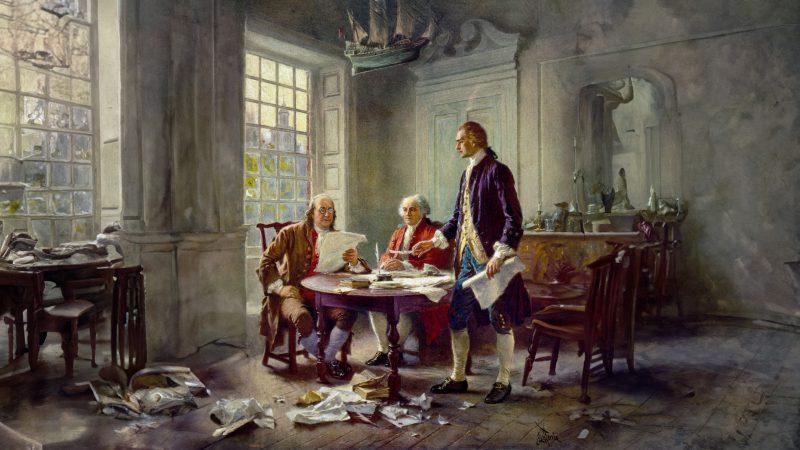

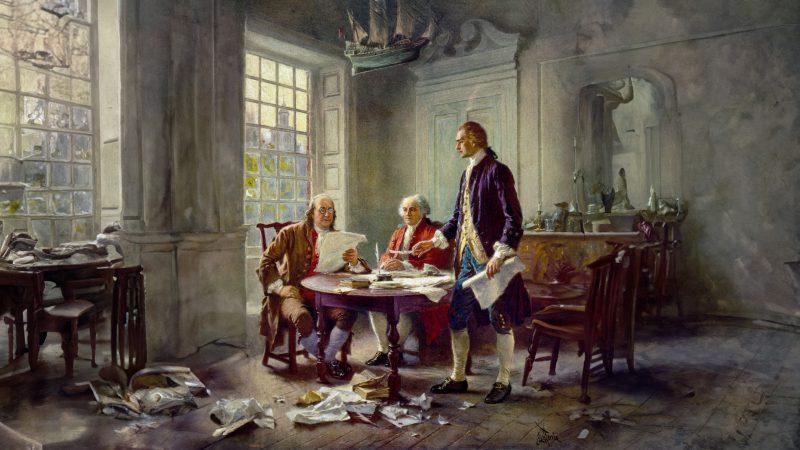

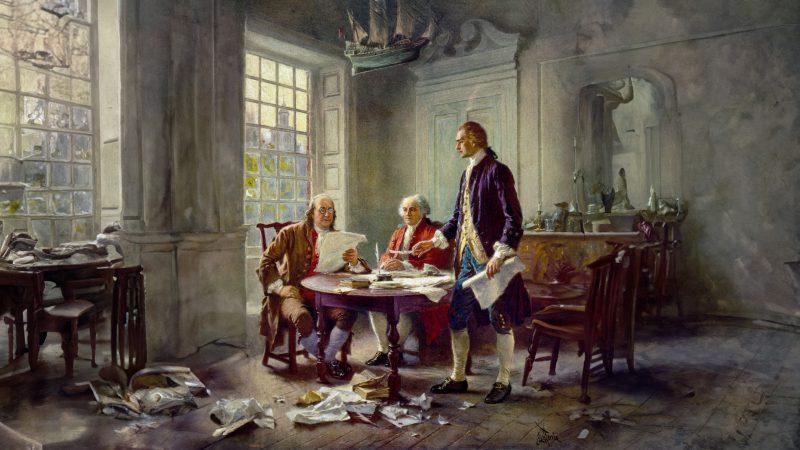

Writing the Declaration of Independence, 1776 by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris (Image via: Wikimedia: Public Domain)

When the American War of Independence was concluded, America’s Founding Fathers established their new nation on the values of the Enlightenment. From Hobbes and Locke to Rousseau and Voltaire a new modern worldview emerged into existence with the Modern era.

This worldview transformed the Medieval Feudalistic ethic which saw rulers as chosen by God and replaced it with the idea of the Social Contract whereby these rulers were servants of the people whose purpose was to ensure the protection and well-being of their subjects. Thus this attitude changed the way people looked at their leaders. And it opened the path to revolution when leaders failed to uphold their duties.

Another key theme of Enlightenment thought was individualism. The English philosopher John Locke emphasised, a century before the American Revolution, the rights of individuals which he formulated as “life, liberty and property” — a phrase that Thomas Jefferson was to slightly adapt when writing the Declaration of Independence to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”.

The rights of the individual became sacred and the equality of all individuals was a foundational belief of this new creed. Liberty was the Enlightenment’s dream for her children — so long as this liberty didn’t interfere with that of others: “your freedom to swing your fist” as the old saying goes “ends at my nose”.

These two themes converged in the rise of modernity’s anointed form of governance: democracy. While the Founding Fathers initially defended themselves against accusations from Europe that their nation was a democracy, it’s an idea Americans soon came to embrace and in more recent times it’s become such an unquestioned good that it justifies the invasion of other nations who must also be liberated whether they like it or not.

Democracy emphasises the value of the individual and styles itself as government of the people by the people. As modernity and democracy have matured, the Enlightenment promises of liberty and equality have become increasingly realised in democratic nations across the world.

The vote was extended from the landed elite to all free men then women. Slavery was abolished and these freed individuals given more rights (after their fair share of struggle to shake the system from its hypocritical slumber).

Where status had been attached to more fixed traits in the hereditary aristocratic hierarchies of the Medieval, in the modern egalitarian societies, one’s value in society was no longer determined at birth. Now one’s achievements as an individual were supposed to determine their status. A new era was born of unheard of freedom and possibility. Social mobility was possible and the so-called American Dream wrapped itself around the hearts of Americans and aspiring immigrants from across the world.

The doctrine of equality quickly took root in the American nation. In 1791, the geographer Jedidiah Morse (whose son developed Morse code) wrote of New England:

“where every man thinks himself at least as good as his neighbours, and believes that all mankind have, or ought to possess, equal rights.”

The Shadow of Equality

But it was not long before the dark side of equality began to rear its head. The shining beacon of liberty and equality at a social level cast a deep and dark shadow at the level of individual psychology. This better world put a heavy burden on the heart of each individual.

In his 1835 work Democracy in America, the French writer Alexis de Tocqueville writes about what he has discerned about American society from his travels in the new nation. In a chapter titled “Why the Americans are Often So Restless in the Midst of Their Prosperity” he writes:

“When all the prerogatives of birth and fortune have been abolished, when every profession is open to everyone, an ambitious man may think it is easy to launch himself on a great career and feel that he has been called to no common destiny. But this is a delusion which experience quickly corrects. When inequality is the general rule in society, the greatest inequalities attract no attention. But when everything is more or less level, the slightest variation is noticed… That is the reason for the strange melancholy often haunting inhabitants of democracies in the midst of abundance and of that disgust with life sometimes gripping them even in calm and easy circumstances.”

The egalitarian democracies of modern times cultivate an attitude of equality in us. From the President or Prime Minister to the men or women on the street, we are all equal. This levelling of society unleashes all the torrents of envy an inherently unequal society keeps in check. We are drowning in comparison. As Alain de Botton puts it in his book Status Anxiety:

“the more people we take to be our equals and compare ourselves to, the more people there will be to envy.”

When we were all peasants whose biggest shift in circumstances was a move to another lord’s land, this was a non-problem. But when our siblings and our former classmates or our Facebook friends can become millionaire entrepreneurs or celebrities or sports stars this ceases to be a trivial problem.

This is the great Pandora’s Box that was opened by the egalitarian liberty of modern democratic society. In Democracy in America de Tocqueville talks about how this shift affected the psychology of servants.

At first, the unlimited possibility brought a cheerfulness. But when these delusions of grandeur crashed against the cliffs of experience for the majority of individuals the mood shifted.

These servants could no longer be happy simply as servants since the press and public opinion imprinted on them their ability to become businessmen, judges, scientists or presidents. And so, as de Tocqueville noted, as time passed and the majority failed to pull off this rise by the bootstraps

“their mood darkened, that bitterness took hold and choked their spirits and their hatred of themselves and their masters grew fierce.”

In the 21st Century

This trend towards discontent did not disappear with the generations. This may serve to illuminate a quote that we’ve meditated upon in the past on The Living Philosophy. It’s what I call the Seligman Diagnosis from Martin Seligman — who as head of the American Psychological Association founded the Positive Psychology movement — in his 2002 book Authentic Happiness:

“Mounting over the last forty years in every wealthy country on the globe, there has been a startling increase in depression. Depression is now ten times as prevalent as it was in 1960, and it strikes at a much younger age. The mean age of a person’s first episode of depression forty years ago was 29.5, while today it is 14.5 years. This is a paradox, since every objective indicator of well-being—purchasing power, amount of education, availability of music, and nutrition—has been going north, while every indicator of subjective well-being has been going south. How is this epidemic to be explained?”

In The Social Dilemma, Jonathan Haidt shows how the intervening decades since Seligman’s work has only served to send this pattern into overdrive:

The sense of comparison which our modern egalitarian worldview birthed and which democracy universally mandated created a crushing level of comparison in the citizens of this new era. Social Media is not the demon that created the Mental Health crisis; it is the technology which took the underlying pattern and amplified it — democratising the misery of comparison.

So what are we to do?

Medieval Eden

The Middle Ages were no picnic. The vast majority of the population of Medieval Europe were peasants. They were as Alain de Botton put it:

“poor, undernourished, cold fearful and dead — usually following some agony — before their fortieth birthdays. After a lifetime of work their most expensive possession might have been a cow, a goat or a pot. Famine had never been far away and diseases had been rife; among the most common were rickets, ulcers, tuberculosis, leprosy, abscesses, gangrene, tumours and cankers.”

In short, Medieval life was far from ideal. Viewed from the outside it was a miserable existence. As serfs they weren’t entirely free; the most common type of serf — the villein — would have to pay their lord for loss of income just to move away to another holding if for example they were unfortunate enough to fall in love with someone outside their lord’s domain. The national government — or rather the kingdom’s government — was no better. And all this without mentioning the rather frequent horrors of war.

Despite all this, the Medieval wasn’t entirely worse than the modern era that has followed. So says de Tocqueville who had seen the world from both sides; he writes:

“When royal power supported by aristocracies governed nations, society, despite all its wretchedness, enjoyed several types of happiness which are difficult to appreciate today. Having never conceived the possibility of a social state other than the one they knew and never expecting to become equal to their leaders, the people did not question their rights. They felt neither repugnance nor degradation in submitting to severities, which seemed to them like inevitable ills sent by God. The serf considered his inferiority as an effect of the immutable order of nature. Consequently a sort of goodwill was established between classes so differently favoured by fortune. One found inequality in society, but men’s souls were not degraded thereby.”

What to do with Equality

With the opening of the Pandora’s Box of equality two psychological coping strategies have emerged. One reaction is to take the paradigm for granted and to strive to realise the promise of the world of equality. This usually entails working as hard as we can at jobs we don’t like and filling the void of our falling short of our ideal with all the nice things that signal to others we’ve reached it. Houses, cars, holidays, handbags or saunas. We plunge ourselves into debt so we can at least create an illusion of running a good race. In short, keeping up with the Joneses.

The other option is ressentiment. The problem isn’t equality, assumes the mind of ressentiment, the problem is that equality hasn’t been fully realised; the problem is that the world is still unjustly unequal. Were things to be justly arranged according to equality and liberty then things would be better; people would be happy.

And so filled with hatred for the injustices for the hypocritical machine we try to change it. We protest, we sing songs about better worlds and of rich men north of Richmond and content ourselves with the knowledge that maybe we are good enough but the world isn’t. Those with more money, more connections, the right gender, skin colour, nationality or creed succeed because this world is built for them. If only the world were truly equal then we could all be content.

But if the argument of this article is sound, then both of these approaches — the American Dreamer and the ressentimentful activist — are working off false premises. They are blinded by the value of liberty and equality. They think that a little more salt water will quench their thirst. But what if they are wrong? What if equality is the obstacle, not the way?

The Limitations of Meritocracy

The dream of Thomas Jefferson was to “create an opening for the aristocracy of virtue and talent” to replace the old aristocracy of privilege. Seen from the vantage point of general happiness, this dream embodies the worst of both worlds.

The end result is a world of inequality — where the majority are miserable. In the Jeffersonian utopia, those with the highest IQ have the competitive advantage. The aristocratic order is still fixed at birth but one must wait to see how the chips will land.

Of course it’s not so simple as that. An individual with higher trait industriousness (i.e. more temperamentally inclined to hard work) will outperform their similarly intelligent peers. And so in this aristocracy of virtue and talent we are incentivised to sacrifice more and more for this talent and virtue. One’s status in such a meritocracy is never guaranteed. It is always precarious. And so we are incentivised to sacrifice that which doesn’t advance us: the moments of small-talk and silence and gossip that once bound our communities together have been optimised out — victims or the modern fetish against friction; victims of the scrambling for the peak that the status anxiety of equality drives us to.

As any soldier of ressentiment will tell you, we do not live in a world where the aristocracy of privilege has been dissolved. Inherited wealth, connections, and pigmentation still account for much of our upper echelons. But we live in enough of an approximation to Jefferson’s utopia to realise its costs.

In a world of Instagram and LinkedIn we are as Yeats put it “sick with desire/And fastened to a dying animal”. We are playing a game in which there must be losers and we are playing at a scale where the winners are warped by their success into something more like a machine than a human. Technology has turbocharged the egalitarian dystopia of the Enlightenment value system.

And so here we stand. Behind us a Medieval world of inequality, disease and deprivation; around us a world of sci-fi abundance which amounts to the old water water everywhere but not a drop to drink. Our modern value system tells us what need is more equality, more liberty.

We live in a better world; but we’ve never been more miserable. And so we’ve returned to our opening question: the value of Eden’s fruit. From the outside there is no comparison. Modern life has overabundant food, air conditioning and automobiles; we have smartphones, refrigerators and low infant mortality rates. The Medieval by comparison had none of these things.

Seen from the inside however a different story emerges. While the material externalities might fool us, it is not obvious that modern humans are any happier than Medieval humans. We live in a better world — of this there is no doubt. We have all the material benefits of progress. And we have all the social benefits of progress — the liberty and equality we’ve been harping on about. But we live in a world where suicide is the second biggest killer of men. We live in a world where depression and self-harm are affecting more people and at younger ages. We live in a world of abundance but like the Buddhist realm of Hungry Ghosts we are unable to gain an ounce of satisfaction from this.

And even if we could change this state of affairs, it is unclear that we ought to if we value our survival. This modern capitalist society, by its very dedication to growth at the cost of the individual, can, has and does outcompete every other social arrangement at least over the short- to mid-term. This evolutionary force pushes us even beyond this planet. We are it seems victims of a Nature that as Tennyson put it is “red in tooth and claw”. Our contentment is a sacrifice at the altar of evolutionary competition.

It seems we are the victims of a Faustian pact. We have truth and power and a freer world but inside our souls have become deserts.

We know that the economy must grow but it’s no longer clear why. If it’s not making a happier world then why? Other than survival what is the purpose of it all? What are we doing here?

There’s an old saying that ignorance is bliss. When it comes down to it this is the lingering question of the Garden of Eden and it is the question of modernity; We can frame it like this:

Would you rather be happier or live in a better world?

Would you rather the ignorant bliss of Eden or would you like your eyes opened to knowledge of good and evil though this knowledge breaks your heart?

Our modern faith assumes that these two go together but history and practical experience has taught us otherwise. The fruit of the great modern project of liberty, equality and democracy was not what we expected. Like Adam and Eve we expected a sweet improvement on our former state. Instead we have found the fruit bitter and now we must toil the hard earth outside the Eden of our ignorance.

We expected our material, technological and social progress to bring with it progress in happiness and well-being. This has not been the case.

From the American War of Independence and the French Revolution to the Civil Rights Movement and the Arab Spring, the doctrine of equality has brought us closer to the image of Paradise but paradoxically it has left us feeling more and more like Hell.

The terrible beauty of modernity has made us more equal but also more hateful, more depressed and more envious. We keep telling ourselves that if only this were improved or that was improved then utopia would ensue. But few of us believe in this utopian horizon anymore. Disoriented we have collapsed into a rudderless crisis where we wholeheartedly embrace the crisis of the day and just as readily move on to the next one tomorrow as our algorithm and feeds demand. The cause of the day drives the cause of yesterday from our mind; what remains is the feeling of outrage and anger at the state of the world.

In this instalment we are going to look at this mixed brew of equality and its connection to the previous instalments’s subject ressentiment. We’ll look at the early days of America and how social media has turbocharged our productive discontent in the 21st century.

Democracy in America

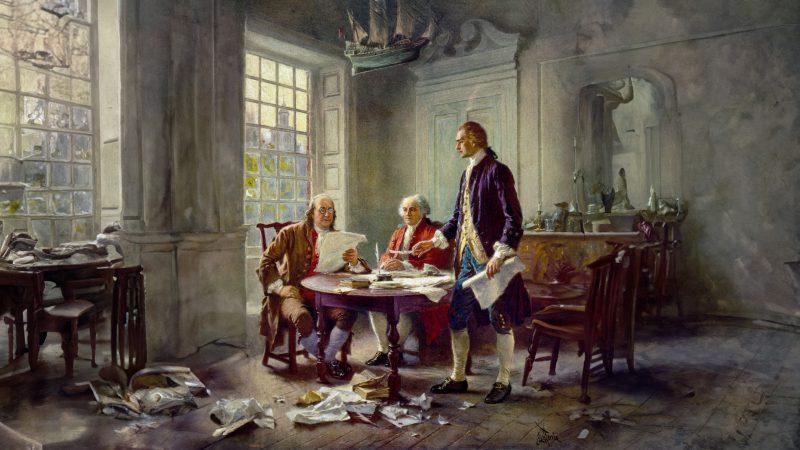

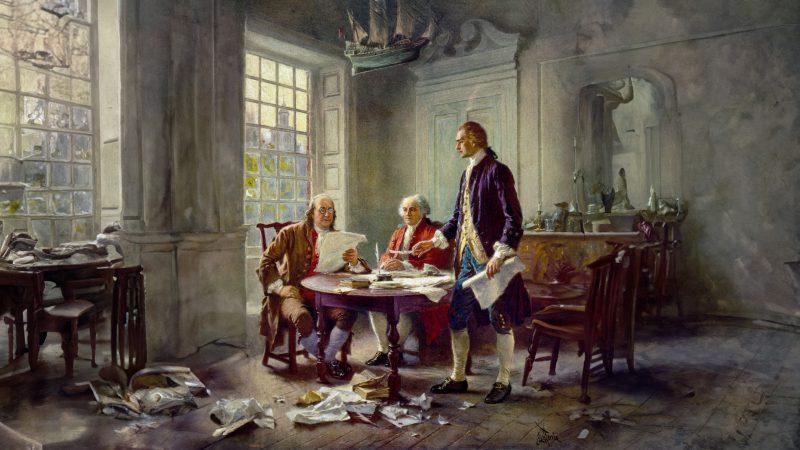

Writing the Declaration of Independence, 1776 by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris (Image via: Wikimedia: Public Domain)

When the American War of Independence was concluded, America’s Founding Fathers established their new nation on the values of the Enlightenment. From Hobbes and Locke to Rousseau and Voltaire a new modern worldview emerged into existence with the Modern era.

This worldview transformed the Medieval Feudalistic ethic which saw rulers as chosen by God and replaced it with the idea of the Social Contract whereby these rulers were servants of the people whose purpose was to ensure the protection and well-being of their subjects. Thus this attitude changed the way people looked at their leaders. And it opened the path to revolution when leaders failed to uphold their duties.

Another key theme of Enlightenment thought was individualism. The English philosopher John Locke emphasised, a century before the American Revolution, the rights of individuals which he formulated as “life, liberty and property” — a phrase that Thomas Jefferson was to slightly adapt when writing the Declaration of Independence to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”.

The rights of the individual became sacred and the equality of all individuals was a foundational belief of this new creed. Liberty was the Enlightenment’s dream for her children — so long as this liberty didn’t interfere with that of others: “your freedom to swing your fist” as the old saying goes “ends at my nose”.

These two themes converged in the rise of modernity’s anointed form of governance: democracy. While the Founding Fathers initially defended themselves against accusations from Europe that their nation was a democracy, it’s an idea Americans soon came to embrace and in more recent times it’s become such an unquestioned good that it justifies the invasion of other nations who must also be liberated whether they like it or not.

Democracy emphasises the value of the individual and styles itself as government of the people by the people. As modernity and democracy have matured, the Enlightenment promises of liberty and equality have become increasingly realised in democratic nations across the world.

The vote was extended from the landed elite to all free men then women. Slavery was abolished and these freed individuals given more rights (after their fair share of struggle to shake the system from its hypocritical slumber).

Where status had been attached to more fixed traits in the hereditary aristocratic hierarchies of the Medieval, in the modern egalitarian societies, one’s value in society was no longer determined at birth. Now one’s achievements as an individual were supposed to determine their status. A new era was born of unheard of freedom and possibility. Social mobility was possible and the so-called American Dream wrapped itself around the hearts of Americans and aspiring immigrants from across the world.

The doctrine of equality quickly took root in the American nation. In 1791, the geographer Jedidiah Morse (whose son developed Morse code) wrote of New England:

“where every man thinks himself at least as good as his neighbours, and believes that all mankind have, or ought to possess, equal rights.”

The Shadow of Equality

But it was not long before the dark side of equality began to rear its head. The shining beacon of liberty and equality at a social level cast a deep and dark shadow at the level of individual psychology. This better world put a heavy burden on the heart of each individual.

In his 1835 work Democracy in America, the French writer Alexis de Tocqueville writes about what he has discerned about American society from his travels in the new nation. In a chapter titled “Why the Americans are Often So Restless in the Midst of Their Prosperity” he writes:

“When all the prerogatives of birth and fortune have been abolished, when every profession is open to everyone, an ambitious man may think it is easy to launch himself on a great career and feel that he has been called to no common destiny. But this is a delusion which experience quickly corrects. When inequality is the general rule in society, the greatest inequalities attract no attention. But when everything is more or less level, the slightest variation is noticed… That is the reason for the strange melancholy often haunting inhabitants of democracies in the midst of abundance and of that disgust with life sometimes gripping them even in calm and easy circumstances.”

The egalitarian democracies of modern times cultivate an attitude of equality in us. From the President or Prime Minister to the men or women on the street, we are all equal. This levelling of society unleashes all the torrents of envy an inherently unequal society keeps in check. We are drowning in comparison. As Alain de Botton puts it in his book Status Anxiety:

“the more people we take to be our equals and compare ourselves to, the more people there will be to envy.”

When we were all peasants whose biggest shift in circumstances was a move to another lord’s land, this was a non-problem. But when our siblings and our former classmates or our Facebook friends can become millionaire entrepreneurs or celebrities or sports stars this ceases to be a trivial problem.

This is the great Pandora’s Box that was opened by the egalitarian liberty of modern democratic society. In Democracy in America de Tocqueville talks about how this shift affected the psychology of servants.

At first, the unlimited possibility brought a cheerfulness. But when these delusions of grandeur crashed against the cliffs of experience for the majority of individuals the mood shifted.

These servants could no longer be happy simply as servants since the press and public opinion imprinted on them their ability to become businessmen, judges, scientists or presidents. And so, as de Tocqueville noted, as time passed and the majority failed to pull off this rise by the bootstraps

“their mood darkened, that bitterness took hold and choked their spirits and their hatred of themselves and their masters grew fierce.”

In the 21st Century

This trend towards discontent did not disappear with the generations. This may serve to illuminate a quote that we’ve meditated upon in the past on The Living Philosophy. It’s what I call the Seligman Diagnosis from Martin Seligman — who as head of the American Psychological Association founded the Positive Psychology movement — in his 2002 book Authentic Happiness:

“Mounting over the last forty years in every wealthy country on the globe, there has been a startling increase in depression. Depression is now ten times as prevalent as it was in 1960, and it strikes at a much younger age. The mean age of a person’s first episode of depression forty years ago was 29.5, while today it is 14.5 years. This is a paradox, since every objective indicator of well-being—purchasing power, amount of education, availability of music, and nutrition—has been going north, while every indicator of subjective well-being has been going south. How is this epidemic to be explained?”

In The Social Dilemma, Jonathan Haidt shows how the intervening decades since Seligman’s work has only served to send this pattern into overdrive:

The sense of comparison which our modern egalitarian worldview birthed and which democracy universally mandated created a crushing level of comparison in the citizens of this new era. Social Media is not the demon that created the Mental Health crisis; it is the technology which took the underlying pattern and amplified it — democratising the misery of comparison.

So what are we to do?

Medieval Eden

The Middle Ages were no picnic. The vast majority of the population of Medieval Europe were peasants. They were as Alain de Botton put it:

“poor, undernourished, cold fearful and dead — usually following some agony — before their fortieth birthdays. After a lifetime of work their most expensive possession might have been a cow, a goat or a pot. Famine had never been far away and diseases had been rife; among the most common were rickets, ulcers, tuberculosis, leprosy, abscesses, gangrene, tumours and cankers.”

In short, Medieval life was far from ideal. Viewed from the outside it was a miserable existence. As serfs they weren’t entirely free; the most common type of serf — the villein — would have to pay their lord for loss of income just to move away to another holding if for example they were unfortunate enough to fall in love with someone outside their lord’s domain. The national government — or rather the kingdom’s government — was no better. And all this without mentioning the rather frequent horrors of war.

Despite all this, the Medieval wasn’t entirely worse than the modern era that has followed. So says de Tocqueville who had seen the world from both sides; he writes:

“When royal power supported by aristocracies governed nations, society, despite all its wretchedness, enjoyed several types of happiness which are difficult to appreciate today. Having never conceived the possibility of a social state other than the one they knew and never expecting to become equal to their leaders, the people did not question their rights. They felt neither repugnance nor degradation in submitting to severities, which seemed to them like inevitable ills sent by God. The serf considered his inferiority as an effect of the immutable order of nature. Consequently a sort of goodwill was established between classes so differently favoured by fortune. One found inequality in society, but men’s souls were not degraded thereby.”

What to do with Equality

With the opening of the Pandora’s Box of equality two psychological coping strategies have emerged. One reaction is to take the paradigm for granted and to strive to realise the promise of the world of equality. This usually entails working as hard as we can at jobs we don’t like and filling the void of our falling short of our ideal with all the nice things that signal to others we’ve reached it. Houses, cars, holidays, handbags or saunas. We plunge ourselves into debt so we can at least create an illusion of running a good race. In short, keeping up with the Joneses.

The other option is ressentiment. The problem isn’t equality, assumes the mind of ressentiment, the problem is that equality hasn’t been fully realised; the problem is that the world is still unjustly unequal. Were things to be justly arranged according to equality and liberty then things would be better; people would be happy.

And so filled with hatred for the injustices for the hypocritical machine we try to change it. We protest, we sing songs about better worlds and of rich men north of Richmond and content ourselves with the knowledge that maybe we are good enough but the world isn’t. Those with more money, more connections, the right gender, skin colour, nationality or creed succeed because this world is built for them. If only the world were truly equal then we could all be content.

But if the argument of this article is sound, then both of these approaches — the American Dreamer and the ressentimentful activist — are working off false premises. They are blinded by the value of liberty and equality. They think that a little more salt water will quench their thirst. But what if they are wrong? What if equality is the obstacle, not the way?

The Limitations of Meritocracy

The dream of Thomas Jefferson was to “create an opening for the aristocracy of virtue and talent” to replace the old aristocracy of privilege. Seen from the vantage point of general happiness, this dream embodies the worst of both worlds.

The end result is a world of inequality — where the majority are miserable. In the Jeffersonian utopia, those with the highest IQ have the competitive advantage. The aristocratic order is still fixed at birth but one must wait to see how the chips will land.

Of course it’s not so simple as that. An individual with higher trait industriousness (i.e. more temperamentally inclined to hard work) will outperform their similarly intelligent peers. And so in this aristocracy of virtue and talent we are incentivised to sacrifice more and more for this talent and virtue. One’s status in such a meritocracy is never guaranteed. It is always precarious. And so we are incentivised to sacrifice that which doesn’t advance us: the moments of small-talk and silence and gossip that once bound our communities together have been optimised out — victims or the modern fetish against friction; victims of the scrambling for the peak that the status anxiety of equality drives us to.

As any soldier of ressentiment will tell you, we do not live in a world where the aristocracy of privilege has been dissolved. Inherited wealth, connections, and pigmentation still account for much of our upper echelons. But we live in enough of an approximation to Jefferson’s utopia to realise its costs.

In a world of Instagram and LinkedIn we are as Yeats put it “sick with desire/And fastened to a dying animal”. We are playing a game in which there must be losers and we are playing at a scale where the winners are warped by their success into something more like a machine than a human. Technology has turbocharged the egalitarian dystopia of the Enlightenment value system.

And so here we stand. Behind us a Medieval world of inequality, disease and deprivation; around us a world of sci-fi abundance which amounts to the old water water everywhere but not a drop to drink. Our modern value system tells us what need is more equality, more liberty.

We live in a better world; but we’ve never been more miserable. And so we’ve returned to our opening question: the value of Eden’s fruit. From the outside there is no comparison. Modern life has overabundant food, air conditioning and automobiles; we have smartphones, refrigerators and low infant mortality rates. The Medieval by comparison had none of these things.

Seen from the inside however a different story emerges. While the material externalities might fool us, it is not obvious that modern humans are any happier than Medieval humans. We live in a better world — of this there is no doubt. We have all the material benefits of progress. And we have all the social benefits of progress — the liberty and equality we’ve been harping on about. But we live in a world where suicide is the second biggest killer of men. We live in a world where depression and self-harm are affecting more people and at younger ages. We live in a world of abundance but like the Buddhist realm of Hungry Ghosts we are unable to gain an ounce of satisfaction from this.

And even if we could change this state of affairs, it is unclear that we ought to if we value our survival. This modern capitalist society, by its very dedication to growth at the cost of the individual, can, has and does outcompete every other social arrangement at least over the short- to mid-term. This evolutionary force pushes us even beyond this planet. We are it seems victims of a Nature that as Tennyson put it is “red in tooth and claw”. Our contentment is a sacrifice at the altar of evolutionary competition.

It seems we are the victims of a Faustian pact. We have truth and power and a freer world but inside our souls have become deserts.

We know that the economy must grow but it’s no longer clear why. If it’s not making a happier world then why? Other than survival what is the purpose of it all? What are we doing here?

There’s an old saying that ignorance is bliss. When it comes down to it this is the lingering question of the Garden of Eden and it is the question of modernity; We can frame it like this:

Would you rather be happier or live in a better world?

Would you rather the ignorant bliss of Eden or would you like your eyes opened to knowledge of good and evil though this knowledge breaks your heart?

Our modern faith assumes that these two go together but history and practical experience has taught us otherwise. The fruit of the great modern project of liberty, equality and democracy was not what we expected. Like Adam and Eve we expected a sweet improvement on our former state. Instead we have found the fruit bitter and now we must toil the hard earth outside the Eden of our ignorance.

We expected our material, technological and social progress to bring with it progress in happiness and well-being. This has not been the case.

From the American War of Independence and the French Revolution to the Civil Rights Movement and the Arab Spring, the doctrine of equality has brought us closer to the image of Paradise but paradoxically it has left us feeling more and more like Hell.

The terrible beauty of modernity has made us more equal but also more hateful, more depressed and more envious. We keep telling ourselves that if only this were improved or that was improved then utopia would ensue. But few of us believe in this utopian horizon anymore. Disoriented we have collapsed into a rudderless crisis where we wholeheartedly embrace the crisis of the day and just as readily move on to the next one tomorrow as our algorithm and feeds demand. The cause of the day drives the cause of yesterday from our mind; what remains is the feeling of outrage and anger at the state of the world.

In this instalment we are going to look at this mixed brew of equality and its connection to the previous instalments’s subject ressentiment. We’ll look at the early days of America and how social media has turbocharged our productive discontent in the 21st century.

Democracy in America

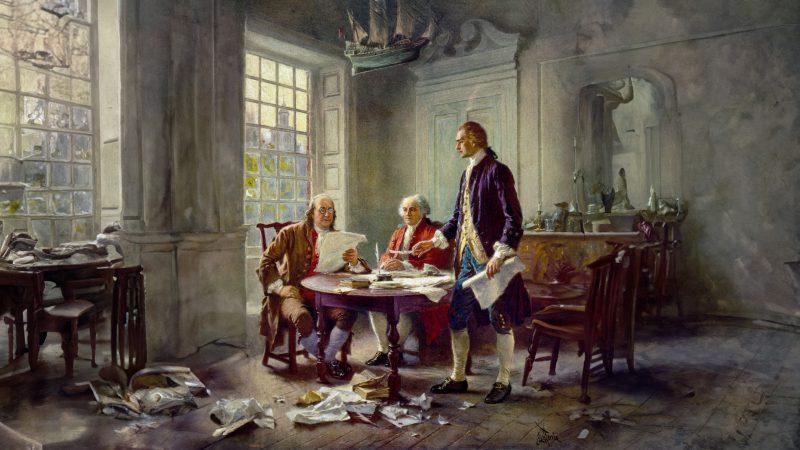

Writing the Declaration of Independence, 1776 by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris (Image via: Wikimedia: Public Domain)

When the American War of Independence was concluded, America’s Founding Fathers established their new nation on the values of the Enlightenment. From Hobbes and Locke to Rousseau and Voltaire a new modern worldview emerged into existence with the Modern era.

This worldview transformed the Medieval Feudalistic ethic which saw rulers as chosen by God and replaced it with the idea of the Social Contract whereby these rulers were servants of the people whose purpose was to ensure the protection and well-being of their subjects. Thus this attitude changed the way people looked at their leaders. And it opened the path to revolution when leaders failed to uphold their duties.

Another key theme of Enlightenment thought was individualism. The English philosopher John Locke emphasised, a century before the American Revolution, the rights of individuals which he formulated as “life, liberty and property” — a phrase that Thomas Jefferson was to slightly adapt when writing the Declaration of Independence to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”.

The rights of the individual became sacred and the equality of all individuals was a foundational belief of this new creed. Liberty was the Enlightenment’s dream for her children — so long as this liberty didn’t interfere with that of others: “your freedom to swing your fist” as the old saying goes “ends at my nose”.

These two themes converged in the rise of modernity’s anointed form of governance: democracy. While the Founding Fathers initially defended themselves against accusations from Europe that their nation was a democracy, it’s an idea Americans soon came to embrace and in more recent times it’s become such an unquestioned good that it justifies the invasion of other nations who must also be liberated whether they like it or not.

Democracy emphasises the value of the individual and styles itself as government of the people by the people. As modernity and democracy have matured, the Enlightenment promises of liberty and equality have become increasingly realised in democratic nations across the world.

The vote was extended from the landed elite to all free men then women. Slavery was abolished and these freed individuals given more rights (after their fair share of struggle to shake the system from its hypocritical slumber).

Where status had been attached to more fixed traits in the hereditary aristocratic hierarchies of the Medieval, in the modern egalitarian societies, one’s value in society was no longer determined at birth. Now one’s achievements as an individual were supposed to determine their status. A new era was born of unheard of freedom and possibility. Social mobility was possible and the so-called American Dream wrapped itself around the hearts of Americans and aspiring immigrants from across the world.

The doctrine of equality quickly took root in the American nation. In 1791, the geographer Jedidiah Morse (whose son developed Morse code) wrote of New England:

“where every man thinks himself at least as good as his neighbours, and believes that all mankind have, or ought to possess, equal rights.”

The Shadow of Equality

But it was not long before the dark side of equality began to rear its head. The shining beacon of liberty and equality at a social level cast a deep and dark shadow at the level of individual psychology. This better world put a heavy burden on the heart of each individual.

In his 1835 work Democracy in America, the French writer Alexis de Tocqueville writes about what he has discerned about American society from his travels in the new nation. In a chapter titled “Why the Americans are Often So Restless in the Midst of Their Prosperity” he writes:

“When all the prerogatives of birth and fortune have been abolished, when every profession is open to everyone, an ambitious man may think it is easy to launch himself on a great career and feel that he has been called to no common destiny. But this is a delusion which experience quickly corrects. When inequality is the general rule in society, the greatest inequalities attract no attention. But when everything is more or less level, the slightest variation is noticed… That is the reason for the strange melancholy often haunting inhabitants of democracies in the midst of abundance and of that disgust with life sometimes gripping them even in calm and easy circumstances.”

The egalitarian democracies of modern times cultivate an attitude of equality in us. From the President or Prime Minister to the men or women on the street, we are all equal. This levelling of society unleashes all the torrents of envy an inherently unequal society keeps in check. We are drowning in comparison. As Alain de Botton puts it in his book Status Anxiety:

“the more people we take to be our equals and compare ourselves to, the more people there will be to envy.”

When we were all peasants whose biggest shift in circumstances was a move to another lord’s land, this was a non-problem. But when our siblings and our former classmates or our Facebook friends can become millionaire entrepreneurs or celebrities or sports stars this ceases to be a trivial problem.

This is the great Pandora’s Box that was opened by the egalitarian liberty of modern democratic society. In Democracy in America de Tocqueville talks about how this shift affected the psychology of servants.

At first, the unlimited possibility brought a cheerfulness. But when these delusions of grandeur crashed against the cliffs of experience for the majority of individuals the mood shifted.

These servants could no longer be happy simply as servants since the press and public opinion imprinted on them their ability to become businessmen, judges, scientists or presidents. And so, as de Tocqueville noted, as time passed and the majority failed to pull off this rise by the bootstraps

“their mood darkened, that bitterness took hold and choked their spirits and their hatred of themselves and their masters grew fierce.”

In the 21st Century

This trend towards discontent did not disappear with the generations. This may serve to illuminate a quote that we’ve meditated upon in the past on The Living Philosophy. It’s what I call the Seligman Diagnosis from Martin Seligman — who as head of the American Psychological Association founded the Positive Psychology movement — in his 2002 book Authentic Happiness:

“Mounting over the last forty years in every wealthy country on the globe, there has been a startling increase in depression. Depression is now ten times as prevalent as it was in 1960, and it strikes at a much younger age. The mean age of a person’s first episode of depression forty years ago was 29.5, while today it is 14.5 years. This is a paradox, since every objective indicator of well-being—purchasing power, amount of education, availability of music, and nutrition—has been going north, while every indicator of subjective well-being has been going south. How is this epidemic to be explained?”

In The Social Dilemma, Jonathan Haidt shows how the intervening decades since Seligman’s work has only served to send this pattern into overdrive:

The sense of comparison which our modern egalitarian worldview birthed and which democracy universally mandated created a crushing level of comparison in the citizens of this new era. Social Media is not the demon that created the Mental Health crisis; it is the technology which took the underlying pattern and amplified it — democratising the misery of comparison.

So what are we to do?

Medieval Eden

The Middle Ages were no picnic. The vast majority of the population of Medieval Europe were peasants. They were as Alain de Botton put it:

“poor, undernourished, cold fearful and dead — usually following some agony — before their fortieth birthdays. After a lifetime of work their most expensive possession might have been a cow, a goat or a pot. Famine had never been far away and diseases had been rife; among the most common were rickets, ulcers, tuberculosis, leprosy, abscesses, gangrene, tumours and cankers.”

In short, Medieval life was far from ideal. Viewed from the outside it was a miserable existence. As serfs they weren’t entirely free; the most common type of serf — the villein — would have to pay their lord for loss of income just to move away to another holding if for example they were unfortunate enough to fall in love with someone outside their lord’s domain. The national government — or rather the kingdom’s government — was no better. And all this without mentioning the rather frequent horrors of war.

Despite all this, the Medieval wasn’t entirely worse than the modern era that has followed. So says de Tocqueville who had seen the world from both sides; he writes:

“When royal power supported by aristocracies governed nations, society, despite all its wretchedness, enjoyed several types of happiness which are difficult to appreciate today. Having never conceived the possibility of a social state other than the one they knew and never expecting to become equal to their leaders, the people did not question their rights. They felt neither repugnance nor degradation in submitting to severities, which seemed to them like inevitable ills sent by God. The serf considered his inferiority as an effect of the immutable order of nature. Consequently a sort of goodwill was established between classes so differently favoured by fortune. One found inequality in society, but men’s souls were not degraded thereby.”

What to do with Equality

With the opening of the Pandora’s Box of equality two psychological coping strategies have emerged. One reaction is to take the paradigm for granted and to strive to realise the promise of the world of equality. This usually entails working as hard as we can at jobs we don’t like and filling the void of our falling short of our ideal with all the nice things that signal to others we’ve reached it. Houses, cars, holidays, handbags or saunas. We plunge ourselves into debt so we can at least create an illusion of running a good race. In short, keeping up with the Joneses.

The other option is ressentiment. The problem isn’t equality, assumes the mind of ressentiment, the problem is that equality hasn’t been fully realised; the problem is that the world is still unjustly unequal. Were things to be justly arranged according to equality and liberty then things would be better; people would be happy.

And so filled with hatred for the injustices for the hypocritical machine we try to change it. We protest, we sing songs about better worlds and of rich men north of Richmond and content ourselves with the knowledge that maybe we are good enough but the world isn’t. Those with more money, more connections, the right gender, skin colour, nationality or creed succeed because this world is built for them. If only the world were truly equal then we could all be content.

But if the argument of this article is sound, then both of these approaches — the American Dreamer and the ressentimentful activist — are working off false premises. They are blinded by the value of liberty and equality. They think that a little more salt water will quench their thirst. But what if they are wrong? What if equality is the obstacle, not the way?

The Limitations of Meritocracy

The dream of Thomas Jefferson was to “create an opening for the aristocracy of virtue and talent” to replace the old aristocracy of privilege. Seen from the vantage point of general happiness, this dream embodies the worst of both worlds.

The end result is a world of inequality — where the majority are miserable. In the Jeffersonian utopia, those with the highest IQ have the competitive advantage. The aristocratic order is still fixed at birth but one must wait to see how the chips will land.

Of course it’s not so simple as that. An individual with higher trait industriousness (i.e. more temperamentally inclined to hard work) will outperform their similarly intelligent peers. And so in this aristocracy of virtue and talent we are incentivised to sacrifice more and more for this talent and virtue. One’s status in such a meritocracy is never guaranteed. It is always precarious. And so we are incentivised to sacrifice that which doesn’t advance us: the moments of small-talk and silence and gossip that once bound our communities together have been optimised out — victims or the modern fetish against friction; victims of the scrambling for the peak that the status anxiety of equality drives us to.

As any soldier of ressentiment will tell you, we do not live in a world where the aristocracy of privilege has been dissolved. Inherited wealth, connections, and pigmentation still account for much of our upper echelons. But we live in enough of an approximation to Jefferson’s utopia to realise its costs.

In a world of Instagram and LinkedIn we are as Yeats put it “sick with desire/And fastened to a dying animal”. We are playing a game in which there must be losers and we are playing at a scale where the winners are warped by their success into something more like a machine than a human. Technology has turbocharged the egalitarian dystopia of the Enlightenment value system.

And so here we stand. Behind us a Medieval world of inequality, disease and deprivation; around us a world of sci-fi abundance which amounts to the old water water everywhere but not a drop to drink. Our modern value system tells us what need is more equality, more liberty.

We live in a better world; but we’ve never been more miserable. And so we’ve returned to our opening question: the value of Eden’s fruit. From the outside there is no comparison. Modern life has overabundant food, air conditioning and automobiles; we have smartphones, refrigerators and low infant mortality rates. The Medieval by comparison had none of these things.

Seen from the inside however a different story emerges. While the material externalities might fool us, it is not obvious that modern humans are any happier than Medieval humans. We live in a better world — of this there is no doubt. We have all the material benefits of progress. And we have all the social benefits of progress — the liberty and equality we’ve been harping on about. But we live in a world where suicide is the second biggest killer of men. We live in a world where depression and self-harm are affecting more people and at younger ages. We live in a world of abundance but like the Buddhist realm of Hungry Ghosts we are unable to gain an ounce of satisfaction from this.

And even if we could change this state of affairs, it is unclear that we ought to if we value our survival. This modern capitalist society, by its very dedication to growth at the cost of the individual, can, has and does outcompete every other social arrangement at least over the short- to mid-term. This evolutionary force pushes us even beyond this planet. We are it seems victims of a Nature that as Tennyson put it is “red in tooth and claw”. Our contentment is a sacrifice at the altar of evolutionary competition.

It seems we are the victims of a Faustian pact. We have truth and power and a freer world but inside our souls have become deserts.

We know that the economy must grow but it’s no longer clear why. If it’s not making a happier world then why? Other than survival what is the purpose of it all? What are we doing here?