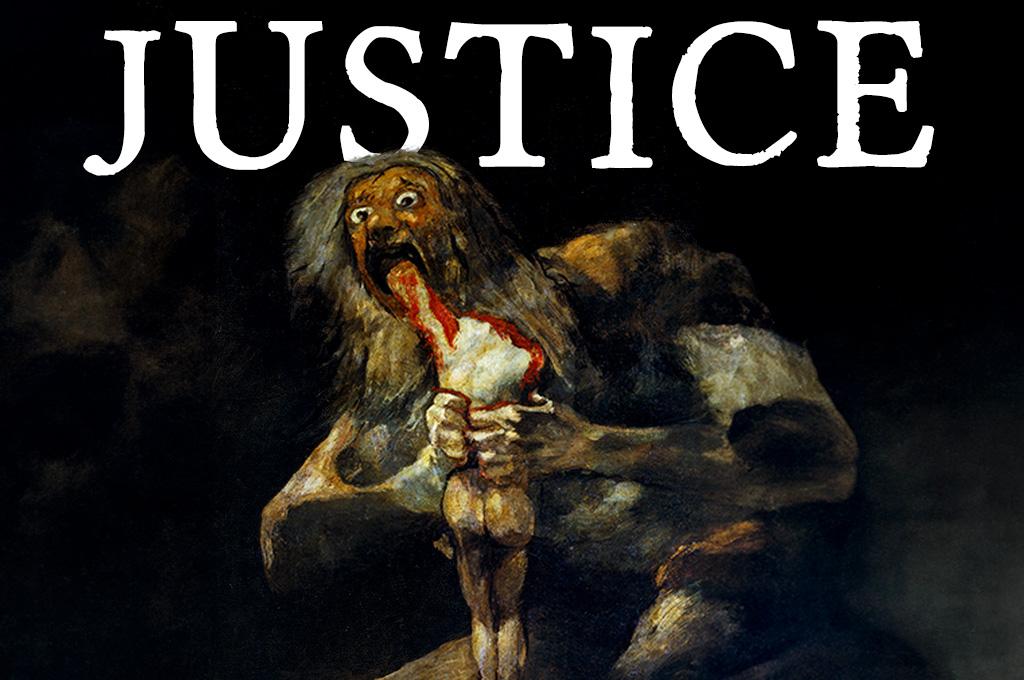

We tend to think of justice as a noble ideal we should strive for and vengeance as a small negative pettiness driven by the darker angels of our nature. But when we drill down on the mechanisms of justice a different image emerges. As the French philosopher and anthropologist René Girard has put it:

“public vengeance is the exclusive property of well-policed societies, and our society calls it the judicial system.”

Nowhere is this Shadow of justice more evident than in our attitude towards criminals; or more accurately our attitudes because we are conflicted when it comes to criminals. We speak two different languages in this domain that often contradict each other; they are the languages of punishment and rehabilitation. This is reflective of the deeper nature of justice that Girard and before him Nietzsche excavated.

These languages pull us in opposite directions; they seem like two different answers to the same question but in fact they are two different human needs striving to be met in the same space. On the one hand we have the thirst for revenge on the part of the victim (and society in general) and over against this we have the desire to create a better society.

In this instalment we are going to focus in on the former — the Shadow side of justice with its origins in vengeance. But it is worth dwelling on the latter for a moment as it serves to bring this Shadow into clearer relief.

Rehabilitation vs Punishment

We are all aware of the horrors of prison. It is covered so commonly in popular culture that we might think of it as fictional but the data says otherwise.

One survey of male prisoners in the midwestern United States found that 21% of inmates said that they had experienced at least one episode of pressured or forced sexual contact since incarcerated in their state, 7% reported that they had been raped, and 4% reported that they had been raped in the last 26 to 30 months.

And aside from the abominable safety of the prisoners we are also aware that this system does not serve a rehabilitating purpose. It is well known that prison doesn’t rehabilitate criminals but instead it turns amateurs into professionals and creates criminal networks and gang affiliations. Within three years of release 68% of prisoners in the United States will reoffend and land right back where they started.

In short the institution of prison makes society worse over time. It is a networking hub for criminality which creates and organises the crime of the future through its dystopian organisation.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. In the 1980s Norway was in a similar state with a recidivism rate of 60-70%. Today that rate has come down to a 20% reoffence rate after one year or 25% after five years. This isn’t due to harsher punishments but quite the opposite. Norway is famous for its so-called open prisons like Halden Prison south of Oslo which has a library and a fully equipped music studio. Rehabilitation, it seems, works.

So why does the rehabilitation model work in Norway but not elsewhere? The argument of this article is that the other drive operating in the criminal sphere takes precedence: the drive for vengeance.

A study in Britain found that while exactly zero Labour Members of Parliament and 20% of Tory MPs supported the death penalty, 50% of the population do. By comparison surveys in the US and Norway have found that 69% of Americans support the death penalty while only 25% of Norwegians do.

It’s a rather tenuous starting point but it seems that there is a greater vengefulness in some populations and this seems to be connected to the emphasis of rehabilitation vs punishment as a way of dealing with criminals.

And so, the argument of this article is that the reason why we accept the horrors of prison is not because we think it improves society but because it satisfies our psychological hunger for revenge. This is not just as victims of crime but as objective citizens reflecting on crimes that had no effect on our lives. We relish the punishment of the wrong-doer. The entire Marvel franchise is built on this principle of justice as punishment and of the demonisation of the wrong-doer.

The better angels of our nature believe in rehabilitation but there is a darker vengeful side to us that believes more strongly in punishment.

As much as we are drawn to the wisdom of the rehabilitation model — which speaks to the old sacred ideas of mercy and forgiveness — we just can’t seem to escape the darker side of justice — even in our metaphysics.

Jesus was different because he believed that God was all-loving and all-merciful. This is the revaluation of the Gospels — the loving of your enemy and the turning of the other cheek. But the New Testament couldn’t sustain this tone beyond the Gospels and the book concludes with the Book of Revelations. This is where the fire and brimstone, the eternal damnation of those who do wrong comes in. If you aren’t good then the devil will shove a burning pitchfork up your ass for all eternity.

While Jesus would have us forgive the prodigal son and slay the fattened calf for him, the good son who remains at home would prefer some degree of vengeance which recognises his loyalty and punishes the bad deeds of his prodigal brother.

And so here we see the familiar tension play out again between rehabilitation and punishment — forgiveness and vengeance. It is debatable which Christianity has been more influential historically — the vengeful fire and brimstone or the loving Communitas of the Gospels. From the vantage point of Irish Catholic culture it certainly seems to be the very un-Jesus punishment element.

Even then, in our most loving and forgiving religions like Christianity, we can’t escape the snapback to the dark origins of justice. So rather than turning away from this collective Shadow, in this article we are going to drill down on this darker foundation of justice and see the true value of this noble ideal.

The Dark Side of Justice

“Wherever justice is practiced and maintained one sees a strong power seeking a means of putting an end to the senseless raging of ressentiment among the weaker powers that stand under it (whether they be groups or individuals) — partly by taking the object of ressentiment out of the hands of revenge.” — Friedrich Nietzsche, The Genealogy of Morals

This is Nietzsche’s diagnosis of the true workings of justice. Where a society without a judicial system leaves resentment and ressentiment build up among its members and is always at risk of an outburst of vigilante revenge, societies with a judicial system take this power out of the hands of the bitter and vengeful individuals.

As Nietzsche frames it, the judicial system takes revenge out of the hands of the affected and carves for itself a monopoly on vengeance.

Nevertheless, despite the shared essence of vengeance and justice, their presence in the world is very different. Girard writes:

“He who exacts his own vengeance is said to “take the law into his own hands.” There is no difference of principle between private and public vengeance; but on the social level, the difference is enormous. Under the public system, an act of vengeance is no longer avenged; the process is terminated, the danger of escalation averted.”

It is worth paying special attention to this final line when seeking to understand the meaning and value of justice: “the danger of escalation averted.”

These quotes regarding vengeance and justice came from Girard’s great work Violence and the Sacred. Girard argues that the purpose of sacrifice in tribal and traditional societies is the same as the justice system in more complex societies: putting an end to vengeance.

Vengeance, on Girard’s account, is like a contagion spreading through the society; a cultural wildfire that can potentially devastate the entire society; he writes:

“Vengeance professes to be an act of reprisal, and every reprisal calls for another reprisal. The crime to which the act of reprisal addresses itself is almost never an unprecedented offense; in almost every case it has been committed in revenge for some prior crime.

“Vengeance then, is an interminable, infinitely repetitive process. Every time it turns up in some part of the community, it threatens to involve the whole social body. There is the risk that the act of vengeance will initiate a chain reaction whose consequences will quickly prove fatal to any society of modest size. The multiplication of reprisals instantaneously puts the very existence of a society in jeopardy, and that is why it is universally proscribed.”

There are countless examples we can give of this chain reaction even in our world of judicial systems. Here in Ireland we could speak of the Troubles where the killing of a Unionist — the camp that wished to remain a part of the United Kingdom — was avenged by the death of a Nationalist — those who wanted a united Ireland. While this historical cause was the origin of the conflict, before long it descended into a series of revenge killings as tit was repaid by tat. This chain of reprisals spilt out of the direct perpetrators. It was simply enough to have the wrong creed or area code to get caught up in this bloody circle of vengeance.

The same dynamics underpin all gang wars from those here in Limerick a couple of decades ago to the Crips and the Bloods of Los Angeles or the conflict between the East Coast and West Coast rappers in the 1990s. One act of violence leads to a reprisal which triggers another and yet another in turn setting off the Girardian chain reaction.

The Hegemony of Justice

This brings us back to Nietzsche’s quote. Justice is a stronger power putting an end to the raging fires of vengeful violence spreading through the community. The stronger hand of institutional justice proclaims the final word. Those who disagree with this judgement will be crushed by the power of this superior justice.

That at least is the idea but of course this doesn’t always go off without a hitch. When the American Federal government moved against slavery in the 19th century, the Southern State slave-owners didn’t accept this as final. Instead they went to war with the institutional power — seeking to revenge themselves on it and reclaim their dominance.

We might also think of the smaller-scale guerrilla movements like the French Resistance during the Second World War, the Black Panthers or the Irish Revolutionaries a century ago and see that one can fight the system in asymmetric warfare also.

These exceptions tie in with our previous explorations into the power of ressentiment to mobilise radical movements which bring about mass social change.

The ideal is that all ressentiment and vengefulness falls on the powerful shoulders of society’s judicial system. So long as the energy is channelled in this direction there may be wars and civil wars, there may be revolutions and protests but what is avoided is a pandemic of revenge spreading through civil society.

The judicial system has the final word. If one side is unhappy they will either have to work within the power of the justice system — with appeals and retrials or they can take the law into their own hands and in turn face the vengeance of the justice system.

Success in such an endeavour usually takes the form of revolution or highly organised gang hierarchies operating in constant tension with the law.

The role of the justice system is to get in the middle of this raging ressentiment and direct all this hatred towards itself. So long as this judicial big brother — whether it’s the court systems and state apparatus of modern states or the Feudalistic hierarchy ending with the king of the Medieval — has the power to backup its claims then society can enjoy a high level of stability. The buck always ends with the greater power of the judicial system. It is this cultural innovation that put an end to the pandemics of revenge spreading through a society.

Justice then is merely its own form of vengeance. It is the glorified legal vengeance of the powerful which takes upon itself the anger and hatred of its victims.

As such it should not surprise us that society tends to care little for the abuse in prisons. These people after all are suffering our collective vengeance. They are the sacrificial victims of complex society. And no matter how much we flatter ourselves with the language of rehabilitation or the mercy of Jesus, we must remember the true origin of justice and that is the vengeful punishing which keeps a lid on the chain reaction of violence that would spread through a society without punishment.

Further Avenues for Research

Looking at Cancel Culture through this lens is a promising avenue of fruitful future research. The libertarian wild-west of the internet which promises ultimate individualism and delivers only mob-psychology has led to an extra-judicial vengefulness.

It would be interesting to consider the implications of this extra-judicial nature of Cancel Culture and whether it is a potential Pandora’s Box setting off a vengeful chain reaction in society. It would be worth doing a comparison between Cancel Culture and the emergence of the Crips and Bloods in LA in the 1970s due to the failures of the judicial system whereby wholesale discrimination against black people moving to LA led to the formation of these gangs and ultimately to the gang war between them. We might also consider whether Cancel Culture is a new wave of justice energy that will be integrated into or prohibited by the monolithic judicial systems of our nations.

Another point worthy of further study is the question of why the rehabilitative perspective prevails in countries like Iceland and Norway. My hunch is that it relates to wealth and social equality but that is just a starting point.

We tend to think of justice as a noble ideal we should strive for and vengeance as a small negative pettiness driven by the darker angels of our nature. But when we drill down on the mechanisms of justice a different image emerges. As the French philosopher and anthropologist René Girard has put it:

“public vengeance is the exclusive property of well-policed societies, and our society calls it the judicial system.”

Nowhere is this Shadow of justice more evident than in our attitude towards criminals; or more accurately our attitudes because we are conflicted when it comes to criminals. We speak two different languages in this domain that often contradict each other; they are the languages of punishment and rehabilitation. This is reflective of the deeper nature of justice that Girard and before him Nietzsche excavated.

These languages pull us in opposite directions; they seem like two different answers to the same question but in fact they are two different human needs striving to be met in the same space. On the one hand we have the thirst for revenge on the part of the victim (and society in general) and over against this we have the desire to create a better society.

In this instalment we are going to focus in on the former — the Shadow side of justice with its origins in vengeance. But it is worth dwelling on the latter for a moment as it serves to bring this Shadow into clearer relief.

Rehabilitation vs Punishment

We are all aware of the horrors of prison. It is covered so commonly in popular culture that we might think of it as fictional but the data says otherwise.

One survey of male prisoners in the midwestern United States found that 21% of inmates said that they had experienced at least one episode of pressured or forced sexual contact since incarcerated in their state, 7% reported that they had been raped, and 4% reported that they had been raped in the last 26 to 30 months.

And aside from the abominable safety of the prisoners we are also aware that this system does not serve a rehabilitating purpose. It is well known that prison doesn’t rehabilitate criminals but instead it turns amateurs into professionals and creates criminal networks and gang affiliations. Within three years of release 68% of prisoners in the United States will reoffend and land right back where they started.

In short the institution of prison makes society worse over time. It is a networking hub for criminality which creates and organises the crime of the future through its dystopian organisation.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. In the 1980s Norway was in a similar state with a recidivism rate of 60-70%. Today that rate has come down to a 20% reoffence rate after one year or 25% after five years. This isn’t due to harsher punishments but quite the opposite. Norway is famous for its so-called open prisons like Halden Prison south of Oslo which has a library and a fully equipped music studio. Rehabilitation, it seems, works.

So why does the rehabilitation model work in Norway but not elsewhere? The argument of this article is that the other drive operating in the criminal sphere takes precedence: the drive for vengeance.

A study in Britain found that while exactly zero Labour Members of Parliament and 20% of Tory MPs supported the death penalty, 50% of the population do. By comparison surveys in the US and Norway have found that 69% of Americans support the death penalty while only 25% of Norwegians do.

It’s a rather tenuous starting point but it seems that there is a greater vengefulness in some populations and this seems to be connected to the emphasis of rehabilitation vs punishment as a way of dealing with criminals.

And so, the argument of this article is that the reason why we accept the horrors of prison is not because we think it improves society but because it satisfies our psychological hunger for revenge. This is not just as victims of crime but as objective citizens reflecting on crimes that had no effect on our lives. We relish the punishment of the wrong-doer. The entire Marvel franchise is built on this principle of justice as punishment and of the demonisation of the wrong-doer.

The better angels of our nature believe in rehabilitation but there is a darker vengeful side to us that believes more strongly in punishment.

As much as we are drawn to the wisdom of the rehabilitation model — which speaks to the old sacred ideas of mercy and forgiveness — we just can’t seem to escape the darker side of justice — even in our metaphysics.

Jesus was different because he believed that God was all-loving and all-merciful. This is the revaluation of the Gospels — the loving of your enemy and the turning of the other cheek. But the New Testament couldn’t sustain this tone beyond the Gospels and the book concludes with the Book of Revelations. This is where the fire and brimstone, the eternal damnation of those who do wrong comes in. If you aren’t good then the devil will shove a burning pitchfork up your ass for all eternity.

While Jesus would have us forgive the prodigal son and slay the fattened calf for him, the good son who remains at home would prefer some degree of vengeance which recognises his loyalty and punishes the bad deeds of his prodigal brother.

And so here we see the familiar tension play out again between rehabilitation and punishment — forgiveness and vengeance. It is debatable which Christianity has been more influential historically — the vengeful fire and brimstone or the loving Communitas of the Gospels. From the vantage point of Irish Catholic culture it certainly seems to be the very un-Jesus punishment element.

Even then, in our most loving and forgiving religions like Christianity, we can’t escape the snapback to the dark origins of justice. So rather than turning away from this collective Shadow, in this article we are going to drill down on this darker foundation of justice and see the true value of this noble ideal.

The Dark Side of Justice

“Wherever justice is practiced and maintained one sees a strong power seeking a means of putting an end to the senseless raging of ressentiment among the weaker powers that stand under it (whether they be groups or individuals) — partly by taking the object of ressentiment out of the hands of revenge.” — Friedrich Nietzsche, The Genealogy of Morals

This is Nietzsche’s diagnosis of the true workings of justice. Where a society without a judicial system leaves resentment and ressentiment build up among its members and is always at risk of an outburst of vigilante revenge, societies with a judicial system take this power out of the hands of the bitter and vengeful individuals.

As Nietzsche frames it, the judicial system takes revenge out of the hands of the affected and carves for itself a monopoly on vengeance.

Nevertheless, despite the shared essence of vengeance and justice, their presence in the world is very different. Girard writes:

“He who exacts his own vengeance is said to “take the law into his own hands.” There is no difference of principle between private and public vengeance; but on the social level, the difference is enormous. Under the public system, an act of vengeance is no longer avenged; the process is terminated, the danger of escalation averted.”

It is worth paying special attention to this final line when seeking to understand the meaning and value of justice: “the danger of escalation averted.”

These quotes regarding vengeance and justice came from Girard’s great work Violence and the Sacred. Girard argues that the purpose of sacrifice in tribal and traditional societies is the same as the justice system in more complex societies: putting an end to vengeance.

Vengeance, on Girard’s account, is like a contagion spreading through the society; a cultural wildfire that can potentially devastate the entire society; he writes:

“Vengeance professes to be an act of reprisal, and every reprisal calls for another reprisal. The crime to which the act of reprisal addresses itself is almost never an unprecedented offense; in almost every case it has been committed in revenge for some prior crime.

“Vengeance then, is an interminable, infinitely repetitive process. Every time it turns up in some part of the community, it threatens to involve the whole social body. There is the risk that the act of vengeance will initiate a chain reaction whose consequences will quickly prove fatal to any society of modest size. The multiplication of reprisals instantaneously puts the very existence of a society in jeopardy, and that is why it is universally proscribed.”

There are countless examples we can give of this chain reaction even in our world of judicial systems. Here in Ireland we could speak of the Troubles where the killing of a Unionist — the camp that wished to remain a part of the United Kingdom — was avenged by the death of a Nationalist — those who wanted a united Ireland. While this historical cause was the origin of the conflict, before long it descended into a series of revenge killings as tit was repaid by tat. This chain of reprisals spilt out of the direct perpetrators. It was simply enough to have the wrong creed or area code to get caught up in this bloody circle of vengeance.

The same dynamics underpin all gang wars from those here in Limerick a couple of decades ago to the Crips and the Bloods of Los Angeles or the conflict between the East Coast and West Coast rappers in the 1990s. One act of violence leads to a reprisal which triggers another and yet another in turn setting off the Girardian chain reaction.

The Hegemony of Justice

This brings us back to Nietzsche’s quote. Justice is a stronger power putting an end to the raging fires of vengeful violence spreading through the community. The stronger hand of institutional justice proclaims the final word. Those who disagree with this judgement will be crushed by the power of this superior justice.

That at least is the idea but of course this doesn’t always go off without a hitch. When the American Federal government moved against slavery in the 19th century, the Southern State slave-owners didn’t accept this as final. Instead they went to war with the institutional power — seeking to revenge themselves on it and reclaim their dominance.

We might also think of the smaller-scale guerrilla movements like the French Resistance during the Second World War, the Black Panthers or the Irish Revolutionaries a century ago and see that one can fight the system in asymmetric warfare also.

These exceptions tie in with our previous explorations into the power of ressentiment to mobilise radical movements which bring about mass social change.

The ideal is that all ressentiment and vengefulness falls on the powerful shoulders of society’s judicial system. So long as the energy is channelled in this direction there may be wars and civil wars, there may be revolutions and protests but what is avoided is a pandemic of revenge spreading through civil society.

The judicial system has the final word. If one side is unhappy they will either have to work within the power of the justice system — with appeals and retrials or they can take the law into their own hands and in turn face the vengeance of the justice system.

Success in such an endeavour usually takes the form of revolution or highly organised gang hierarchies operating in constant tension with the law.

The role of the justice system is to get in the middle of this raging ressentiment and direct all this hatred towards itself. So long as this judicial big brother — whether it’s the court systems and state apparatus of modern states or the Feudalistic hierarchy ending with the king of the Medieval — has the power to backup its claims then society can enjoy a high level of stability. The buck always ends with the greater power of the judicial system. It is this cultural innovation that put an end to the pandemics of revenge spreading through a society.

Justice then is merely its own form of vengeance. It is the glorified legal vengeance of the powerful which takes upon itself the anger and hatred of its victims.

As such it should not surprise us that society tends to care little for the abuse in prisons. These people after all are suffering our collective vengeance. They are the sacrificial victims of complex society. And no matter how much we flatter ourselves with the language of rehabilitation or the mercy of Jesus, we must remember the true origin of justice and that is the vengeful punishing which keeps a lid on the chain reaction of violence that would spread through a society without punishment.

Further Avenues for Research

Looking at Cancel Culture through this lens is a promising avenue of fruitful future research. The libertarian wild-west of the internet which promises ultimate individualism and delivers only mob-psychology has led to an extra-judicial vengefulness.

It would be interesting to consider the implications of this extra-judicial nature of Cancel Culture and whether it is a potential Pandora’s Box setting off a vengeful chain reaction in society. It would be worth doing a comparison between Cancel Culture and the emergence of the Crips and Bloods in LA in the 1970s due to the failures of the judicial system whereby wholesale discrimination against black people moving to LA led to the formation of these gangs and ultimately to the gang war between them. We might also consider whether Cancel Culture is a new wave of justice energy that will be integrated into or prohibited by the monolithic judicial systems of our nations.

Another point worthy of further study is the question of why the rehabilitative perspective prevails in countries like Iceland and Norway. My hunch is that it relates to wealth and social equality but that is just a starting point.

We tend to think of justice as a noble ideal we should strive for and vengeance as a small negative pettiness driven by the darker angels of our nature. But when we drill down on the mechanisms of justice a different image emerges. As the French philosopher and anthropologist René Girard has put it:

“public vengeance is the exclusive property of well-policed societies, and our society calls it the judicial system.”

Nowhere is this Shadow of justice more evident than in our attitude towards criminals; or more accurately our attitudes because we are conflicted when it comes to criminals. We speak two different languages in this domain that often contradict each other; they are the languages of punishment and rehabilitation. This is reflective of the deeper nature of justice that Girard and before him Nietzsche excavated.

These languages pull us in opposite directions; they seem like two different answers to the same question but in fact they are two different human needs striving to be met in the same space. On the one hand we have the thirst for revenge on the part of the victim (and society in general) and over against this we have the desire to create a better society.

In this instalment we are going to focus in on the former — the Shadow side of justice with its origins in vengeance. But it is worth dwelling on the latter for a moment as it serves to bring this Shadow into clearer relief.

Rehabilitation vs Punishment

We are all aware of the horrors of prison. It is covered so commonly in popular culture that we might think of it as fictional but the data says otherwise.

One survey of male prisoners in the midwestern United States found that 21% of inmates said that they had experienced at least one episode of pressured or forced sexual contact since incarcerated in their state, 7% reported that they had been raped, and 4% reported that they had been raped in the last 26 to 30 months.

And aside from the abominable safety of the prisoners we are also aware that this system does not serve a rehabilitating purpose. It is well known that prison doesn’t rehabilitate criminals but instead it turns amateurs into professionals and creates criminal networks and gang affiliations. Within three years of release 68% of prisoners in the United States will reoffend and land right back where they started.

In short the institution of prison makes society worse over time. It is a networking hub for criminality which creates and organises the crime of the future through its dystopian organisation.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. In the 1980s Norway was in a similar state with a recidivism rate of 60-70%. Today that rate has come down to a 20% reoffence rate after one year or 25% after five years. This isn’t due to harsher punishments but quite the opposite. Norway is famous for its so-called open prisons like Halden Prison south of Oslo which has a library and a fully equipped music studio. Rehabilitation, it seems, works.

So why does the rehabilitation model work in Norway but not elsewhere? The argument of this article is that the other drive operating in the criminal sphere takes precedence: the drive for vengeance.

A study in Britain found that while exactly zero Labour Members of Parliament and 20% of Tory MPs supported the death penalty, 50% of the population do. By comparison surveys in the US and Norway have found that 69% of Americans support the death penalty while only 25% of Norwegians do.

It’s a rather tenuous starting point but it seems that there is a greater vengefulness in some populations and this seems to be connected to the emphasis of rehabilitation vs punishment as a way of dealing with criminals.

And so, the argument of this article is that the reason why we accept the horrors of prison is not because we think it improves society but because it satisfies our psychological hunger for revenge. This is not just as victims of crime but as objective citizens reflecting on crimes that had no effect on our lives. We relish the punishment of the wrong-doer. The entire Marvel franchise is built on this principle of justice as punishment and of the demonisation of the wrong-doer.

The better angels of our nature believe in rehabilitation but there is a darker vengeful side to us that believes more strongly in punishment.

As much as we are drawn to the wisdom of the rehabilitation model — which speaks to the old sacred ideas of mercy and forgiveness — we just can’t seem to escape the darker side of justice — even in our metaphysics.

Jesus was different because he believed that God was all-loving and all-merciful. This is the revaluation of the Gospels — the loving of your enemy and the turning of the other cheek. But the New Testament couldn’t sustain this tone beyond the Gospels and the book concludes with the Book of Revelations. This is where the fire and brimstone, the eternal damnation of those who do wrong comes in. If you aren’t good then the devil will shove a burning pitchfork up your ass for all eternity.

While Jesus would have us forgive the prodigal son and slay the fattened calf for him, the good son who remains at home would prefer some degree of vengeance which recognises his loyalty and punishes the bad deeds of his prodigal brother.

And so here we see the familiar tension play out again between rehabilitation and punishment — forgiveness and vengeance. It is debatable which Christianity has been more influential historically — the vengeful fire and brimstone or the loving Communitas of the Gospels. From the vantage point of Irish Catholic culture it certainly seems to be the very un-Jesus punishment element.

Even then, in our most loving and forgiving religions like Christianity, we can’t escape the snapback to the dark origins of justice. So rather than turning away from this collective Shadow, in this article we are going to drill down on this darker foundation of justice and see the true value of this noble ideal.

The Dark Side of Justice

“Wherever justice is practiced and maintained one sees a strong power seeking a means of putting an end to the senseless raging of ressentiment among the weaker powers that stand under it (whether they be groups or individuals) — partly by taking the object of ressentiment out of the hands of revenge.” — Friedrich Nietzsche, The Genealogy of Morals

This is Nietzsche’s diagnosis of the true workings of justice. Where a society without a judicial system leaves resentment and ressentiment build up among its members and is always at risk of an outburst of vigilante revenge, societies with a judicial system take this power out of the hands of the bitter and vengeful individuals.

As Nietzsche frames it, the judicial system takes revenge out of the hands of the affected and carves for itself a monopoly on vengeance.

Nevertheless, despite the shared essence of vengeance and justice, their presence in the world is very different. Girard writes:

“He who exacts his own vengeance is said to “take the law into his own hands.” There is no difference of principle between private and public vengeance; but on the social level, the difference is enormous. Under the public system, an act of vengeance is no longer avenged; the process is terminated, the danger of escalation averted.”

It is worth paying special attention to this final line when seeking to understand the meaning and value of justice: “the danger of escalation averted.”

These quotes regarding vengeance and justice came from Girard’s great work Violence and the Sacred. Girard argues that the purpose of sacrifice in tribal and traditional societies is the same as the justice system in more complex societies: putting an end to vengeance.

Vengeance, on Girard’s account, is like a contagion spreading through the society; a cultural wildfire that can potentially devastate the entire society; he writes:

“Vengeance professes to be an act of reprisal, and every reprisal calls for another reprisal. The crime to which the act of reprisal addresses itself is almost never an unprecedented offense; in almost every case it has been committed in revenge for some prior crime.

“Vengeance then, is an interminable, infinitely repetitive process. Every time it turns up in some part of the community, it threatens to involve the whole social body. There is the risk that the act of vengeance will initiate a chain reaction whose consequences will quickly prove fatal to any society of modest size. The multiplication of reprisals instantaneously puts the very existence of a society in jeopardy, and that is why it is universally proscribed.”

There are countless examples we can give of this chain reaction even in our world of judicial systems. Here in Ireland we could speak of the Troubles where the killing of a Unionist — the camp that wished to remain a part of the United Kingdom — was avenged by the death of a Nationalist — those who wanted a united Ireland. While this historical cause was the origin of the conflict, before long it descended into a series of revenge killings as tit was repaid by tat. This chain of reprisals spilt out of the direct perpetrators. It was simply enough to have the wrong creed or area code to get caught up in this bloody circle of vengeance.

The same dynamics underpin all gang wars from those here in Limerick a couple of decades ago to the Crips and the Bloods of Los Angeles or the conflict between the East Coast and West Coast rappers in the 1990s. One act of violence leads to a reprisal which triggers another and yet another in turn setting off the Girardian chain reaction.

The Hegemony of Justice

This brings us back to Nietzsche’s quote. Justice is a stronger power putting an end to the raging fires of vengeful violence spreading through the community. The stronger hand of institutional justice proclaims the final word. Those who disagree with this judgement will be crushed by the power of this superior justice.

That at least is the idea but of course this doesn’t always go off without a hitch. When the American Federal government moved against slavery in the 19th century, the Southern State slave-owners didn’t accept this as final. Instead they went to war with the institutional power — seeking to revenge themselves on it and reclaim their dominance.

We might also think of the smaller-scale guerrilla movements like the French Resistance during the Second World War, the Black Panthers or the Irish Revolutionaries a century ago and see that one can fight the system in asymmetric warfare also.

These exceptions tie in with our previous explorations into the power of ressentiment to mobilise radical movements which bring about mass social change.

The ideal is that all ressentiment and vengefulness falls on the powerful shoulders of society’s judicial system. So long as the energy is channelled in this direction there may be wars and civil wars, there may be revolutions and protests but what is avoided is a pandemic of revenge spreading through civil society.

The judicial system has the final word. If one side is unhappy they will either have to work within the power of the justice system — with appeals and retrials or they can take the law into their own hands and in turn face the vengeance of the justice system.

Success in such an endeavour usually takes the form of revolution or highly organised gang hierarchies operating in constant tension with the law.

The role of the justice system is to get in the middle of this raging ressentiment and direct all this hatred towards itself. So long as this judicial big brother — whether it’s the court systems and state apparatus of modern states or the Feudalistic hierarchy ending with the king of the Medieval — has the power to backup its claims then society can enjoy a high level of stability. The buck always ends with the greater power of the judicial system. It is this cultural innovation that put an end to the pandemics of revenge spreading through a society.

Justice then is merely its own form of vengeance. It is the glorified legal vengeance of the powerful which takes upon itself the anger and hatred of its victims.

As such it should not surprise us that society tends to care little for the abuse in prisons. These people after all are suffering our collective vengeance. They are the sacrificial victims of complex society. And no matter how much we flatter ourselves with the language of rehabilitation or the mercy of Jesus, we must remember the true origin of justice and that is the vengeful punishing which keeps a lid on the chain reaction of violence that would spread through a society without punishment.

Further Avenues for Research

Looking at Cancel Culture through this lens is a promising avenue of fruitful future research. The libertarian wild-west of the internet which promises ultimate individualism and delivers only mob-psychology has led to an extra-judicial vengefulness.

It would be interesting to consider the implications of this extra-judicial nature of Cancel Culture and whether it is a potential Pandora’s Box setting off a vengeful chain reaction in society. It would be worth doing a comparison between Cancel Culture and the emergence of the Crips and Bloods in LA in the 1970s due to the failures of the judicial system whereby wholesale discrimination against black people moving to LA led to the formation of these gangs and ultimately to the gang war between them. We might also consider whether Cancel Culture is a new wave of justice energy that will be integrated into or prohibited by the monolithic judicial systems of our nations.

Another point worthy of further study is the question of why the rehabilitative perspective prevails in countries like Iceland and Norway. My hunch is that it relates to wealth and social equality but that is just a starting point.