”They were poor, undernourished, cold, fearful and dead — usually following some agony — before their fortieth birthdays. After a lifetime of work their most expensive possession might have been a cow, a goat, or a pot. Famine had never been far away and diseases had been rife; among the most common were rickets, ulcers, tuberculosis, leprosy, abscesses, gangerene, tumours and cankers.”

This is the story that we moderns tell ourselves about the Middle Ages. It fits well with our story about Progress — that things were worse in the past and they keep on getting better. Science and technology have stirred humanity from their sleep of ignorance and misery.

But this isn’t the only story that can be told about the Middle Ages (though it might be the most convenient). There’s another story we can tell about this time and it’s a story that needs to be told because if the story about Progress were true, then the world would want to have been a very very shitty place in the past.

In this instalment we are going to tell this forgotten story of the Middle Ages and what it is that modern society has forgotten. Not to spoil the ending too much but what we’ve forgotten is the meaning of life and how to live it; what we’ve forgotten is the lost art of leisure.

Modern Times

But before we tell the forgotten story, let’s remind ourselves of why we might need another story. After all if you’ve been reading the propaganda of the techno-optimists you might be a little bit baffled. Aren’t things getting better?

Never has there been less poverty, less starvation, less infant mortality and a higher quality of life. This is the story that fits well with de Botton’s quote from the start of the article on the misery of the Middle Ages.

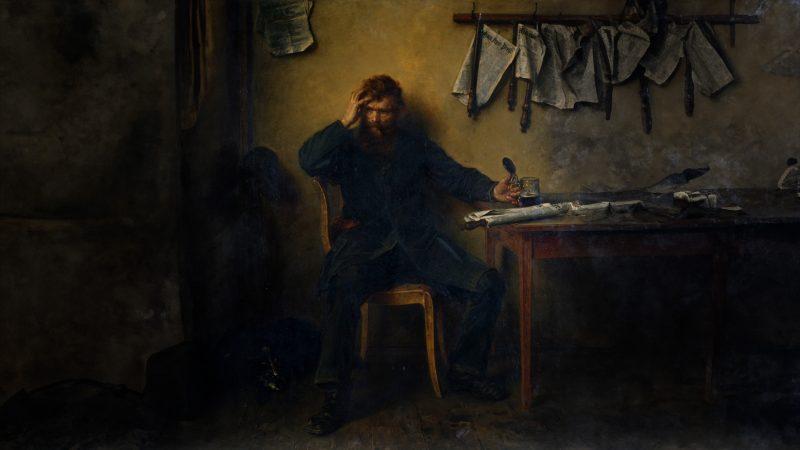

But there’s also a dark side to modern life; as we’ve discussed many times on The Living Philosophy, for every step forward in material well-being we have taken one down into the pits of psychological hell.

In his book Authentic Happiness the former head of the American Psychological Association Martin Seligman outlined the paradox: in the 40 years before the publishing of that book in 2002 the prevalence of depression had increased ten times over and the mean age of your average person’s first depressive episode had come down from 29.5 years to 14.5 years old. The paradox lies in the fact that quality of life improved more in those forty years than perhaps any other time in history.

Fast forward fifteen years and Jonathan Haidt explores the evolution of this trend with social media factored in: self-harm, depression and suicide have skyrocketed among young teens. He correlates this with the emergence of social media but if we look deeper in the data we see that social media has only amplified an already underlying trend. It’s one greater step forward in technology and one giant leap into the depths of psychological Hell.

So it’s reasonable to suppose that while life has unarguably improved in many dimensions it hasn’t improved in every way and we might want to explore possibilities for why that might be so that we can improve things further.

A reasonable way of holding these two stories together is to say that technological progress has improved the external side of life. We have smartphones, electric cars and washing machines. This is good. But it has not improved the internal side of life. So two things are true: we live better lives by any external measure and we are more miserable by any internal measure.

The Other Story

So with that minor shade of doubt cast on the narrative of progress, let’s revisit our Medieval ancestors. Between all the dying from famine and horrible diseases, the people of the Middle Ages found some time to live their lives and to be honest it sounds like we could learn a few things.

And we’re not talking about the knights, dukes and kings here who obviously would have had a decent quality of life as the benefactors of the gross inequality of the times. We’re talking about the people at the bottom of the European hierarchy — the serfs and the peasants.

You see these poor folk had something we have lost — they had lives. Work was still something you did because it was necessary. Leisure was still the rule of life.

According to historians like Gregory Clark and Nora Ritchie, the average country dweller in the 16th century worked somewhere between 150 and 180 days a year. And it’s worth remembering here that the vast majority of people were country dwellers — even at the start of the 19th century 90% of people still lived on farms (a number which had dropped to less than 1% by the 21st century).

There were religious holidays and saints’ days to be celebrating not to mention multiple-day-long village festivals called “ales” to mark major events like weddings, funerals, the harvest and even lambing season. For every bout of work there was a call for a bout of community relaxation.

And on those days when they did finally get to work it wasn’t exactly the opening bell at Wall Street. Here’s how the Bishop of Durham described the work ethic of the peasant in the 1570s:

”The laboring man will take his rest long in the morning; a good piece of the day is spent afore he comes at his work. Then he must have his breakfast, though he have not earned it, at his accustomed hour, else there is grudging and murmuring […] At noon he must have his sleeping time, then his bever in the afternoon, which spendeth a great part of the day.”

For all the technological and medical backwardness of the Middle Ages there was still a sense in which their lives made sense. For the Medieval peasant work was still something you did because it was necessary. You worked today so you had shelter and food tomorrow.

They worked one day a week on the lord’s land which supposedly bought them protection. There was no saving for twenty years so their kid could go to a prestigious university; there was no saving forty years for a retirement where they could finally stop working; they had no thirty-year mortgages nor were they saddled by student debt or any debt. These are all the domain of the modern serf.

It’s obvious to everyone that the Medieval peasant’s quality of life was a lot lower but there are psychological benefits to this simplicity that our culture completely overlooks. As Oliver Burkeman explores in his book Four Thousand Weeks, the difference between the modern serf and the medieval one runs deeper than days worked. What it amounts to is a different relationship with time.

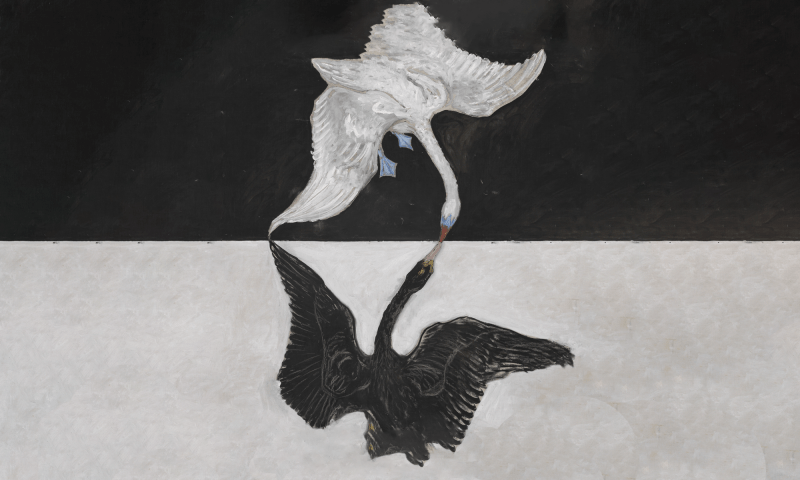

This transformation of our relationship to time happened somewhere in the past few centuries. Some, like sociologist Lewis Mumford, trace it back to the invention of the mechanical clock in the Middle Ages by monks looking to pray more consistently. Others attribute it to the Industrial Revolution and the urbanisation of the developed world. This change is best illustrated through a distinction between two ways of interacting with time. Let’s call one the intrinsic mode and the second the instrumental mode.

In the intrinsic mode we are motivated by things for their own sake; in the instrumental mode we are motivated to do things because of what they lead to; we don’t do them because they are inherently fun or meaningful but because of some benefit they’ll bring us in future.

No society has ever lived entirely in one mode or the other. You don’t boil the kettle or bring your clothes to a dry cleaner because it’s intrinsically enjoyable. You do it because you want a cup of tea or some clean clothes. With instrumentalisation we see things as valuable for what they lead to. The activity is a sacrifice now for a payoff in the future.

On the other hand think of hobbies. And we’re not talking about the kind of hobby which is or at some stage will become a side hustle. I’m talking about old-fashioned embarrassing hobbies. I’m talking about Rod Stewart spending three decades on a model train city. I’m talking about the people out there who crotchet and garden and make steam engines not because they plan on selling them or because the end product will win them some great admiration. I’m talking about hobbies that are done for love. Pure and simple.

The hobby is an exception in modern life. The difference between us citizens of modern life in comparison with the vast majority of our peers throughout history is that the majority of our lives are victims of instrumentalisation.

Even socialising has fallen prey to this trend. Once upon a time you hung out with your friends because it was intrinsically enjoyable but even something as simple as this has been colonised by the psychopathology of social media. As Bo Burnham put it in Inside:

The outside world, the non-digital world, is merely a theatrical space in which one stages and records content for the much more real, much more vital digital space. One should only engage with the outside world as one engages with a coal mine. Suit up, gather what is needed, and return to the surface.

So it’s not enough that instrumentalisation had conquered our work lives, it has now taken over our personal lives as well.

It’s not hard to connect this colonisation of instrumentalisation and the mainstreaming of Nihilism not to mention the mental health crisis and the meaning crisis. Intrinsic activities are inherently meaningful. When you’re having fun you don’t ask why. It’s only when everything you do is for some vague distant future that never arrives that you begin to question what the point of anything is.

The transformation of our relationship with time has brought humanity closer to greatness. We are moving out to the stars we are giving birth to a whole new type of being with AI we have all these shiny gadgets and cool holidays. We are closer to Nietzsche’s goal of the Übermensch. And we have never been so miserable.

Nobody is spared. The rich are probably even more damaged than the rest of us; they got where they are by being great at instrumentalisation. Unlike the Medieval or Ancient aristocracies, the modern elite the bourgeois capitalist doesn’t see work as beneath them as undignified. This couldn’t be further from the truth. They’re even further gone than the rest of us.

Conclusion

The narrative about our modern utopia is trash. Our quality of life has never been so good and our mental health so bad. The question is: why. If the trend of increasing quality of life is coupled to an impoverished internal life then we’ve got a major problem.

But maybe it’s a matter of metrics. The philosophy of modern times so far has been materialism. Materialism sees life in terms of its outer appearance. And so a person with a long span of life and a washing machine looks a lot happier to a materialist than a peasant in a hovel. By the metrics of materialism modernity has been a major success.

And so, what if we shift our metrics towards the phenomenological domain — that is to say what if we measure the good life by the internal state rather than the external one? There are a lot of signs that the materialist domination of our worldview may be waning and we are beginning to appreciate the value of the internal even though it is still a tricky domain to measure.

If so, then we needn’t become reactionaries looking to get back to the Middle Ages but reformers of modernity who are looking to turn the great machine of optimising modernity in the direction of the good life.

It’s hard to believe that a world whose entire identity is based on GDP can make this shift but it’s not outside the bounds of imagination. And so that’s the silver lining we can hope for.

”They were poor, undernourished, cold, fearful and dead — usually following some agony — before their fortieth birthdays. After a lifetime of work their most expensive possession might have been a cow, a goat, or a pot. Famine had never been far away and diseases had been rife; among the most common were rickets, ulcers, tuberculosis, leprosy, abscesses, gangerene, tumours and cankers.”

This is the story that we moderns tell ourselves about the Middle Ages. It fits well with our story about Progress — that things were worse in the past and they keep on getting better. Science and technology have stirred humanity from their sleep of ignorance and misery.

But this isn’t the only story that can be told about the Middle Ages (though it might be the most convenient). There’s another story we can tell about this time and it’s a story that needs to be told because if the story about Progress were true, then the world would want to have been a very very shitty place in the past.

In this instalment we are going to tell this forgotten story of the Middle Ages and what it is that modern society has forgotten. Not to spoil the ending too much but what we’ve forgotten is the meaning of life and how to live it; what we’ve forgotten is the lost art of leisure.

Modern Times

But before we tell the forgotten story, let’s remind ourselves of why we might need another story. After all if you’ve been reading the propaganda of the techno-optimists you might be a little bit baffled. Aren’t things getting better?

Never has there been less poverty, less starvation, less infant mortality and a higher quality of life. This is the story that fits well with de Botton’s quote from the start of the article on the misery of the Middle Ages.

But there’s also a dark side to modern life; as we’ve discussed many times on The Living Philosophy, for every step forward in material well-being we have taken one down into the pits of psychological hell.

In his book Authentic Happiness the former head of the American Psychological Association Martin Seligman outlined the paradox: in the 40 years before the publishing of that book in 2002 the prevalence of depression had increased ten times over and the mean age of your average person’s first depressive episode had come down from 29.5 years to 14.5 years old. The paradox lies in the fact that quality of life improved more in those forty years than perhaps any other time in history.

Fast forward fifteen years and Jonathan Haidt explores the evolution of this trend with social media factored in: self-harm, depression and suicide have skyrocketed among young teens. He correlates this with the emergence of social media but if we look deeper in the data we see that social media has only amplified an already underlying trend. It’s one greater step forward in technology and one giant leap into the depths of psychological Hell.

So it’s reasonable to suppose that while life has unarguably improved in many dimensions it hasn’t improved in every way and we might want to explore possibilities for why that might be so that we can improve things further.

A reasonable way of holding these two stories together is to say that technological progress has improved the external side of life. We have smartphones, electric cars and washing machines. This is good. But it has not improved the internal side of life. So two things are true: we live better lives by any external measure and we are more miserable by any internal measure.

The Other Story

So with that minor shade of doubt cast on the narrative of progress, let’s revisit our Medieval ancestors. Between all the dying from famine and horrible diseases, the people of the Middle Ages found some time to live their lives and to be honest it sounds like we could learn a few things.

And we’re not talking about the knights, dukes and kings here who obviously would have had a decent quality of life as the benefactors of the gross inequality of the times. We’re talking about the people at the bottom of the European hierarchy — the serfs and the peasants.

You see these poor folk had something we have lost — they had lives. Work was still something you did because it was necessary. Leisure was still the rule of life.

According to historians like Gregory Clark and Nora Ritchie, the average country dweller in the 16th century worked somewhere between 150 and 180 days a year. And it’s worth remembering here that the vast majority of people were country dwellers — even at the start of the 19th century 90% of people still lived on farms (a number which had dropped to less than 1% by the 21st century).

There were religious holidays and saints’ days to be celebrating not to mention multiple-day-long village festivals called “ales” to mark major events like weddings, funerals, the harvest and even lambing season. For every bout of work there was a call for a bout of community relaxation.

And on those days when they did finally get to work it wasn’t exactly the opening bell at Wall Street. Here’s how the Bishop of Durham described the work ethic of the peasant in the 1570s:

”The laboring man will take his rest long in the morning; a good piece of the day is spent afore he comes at his work. Then he must have his breakfast, though he have not earned it, at his accustomed hour, else there is grudging and murmuring […] At noon he must have his sleeping time, then his bever in the afternoon, which spendeth a great part of the day.”

For all the technological and medical backwardness of the Middle Ages there was still a sense in which their lives made sense. For the Medieval peasant work was still something you did because it was necessary. You worked today so you had shelter and food tomorrow.

They worked one day a week on the lord’s land which supposedly bought them protection. There was no saving for twenty years so their kid could go to a prestigious university; there was no saving forty years for a retirement where they could finally stop working; they had no thirty-year mortgages nor were they saddled by student debt or any debt. These are all the domain of the modern serf.

It’s obvious to everyone that the Medieval peasant’s quality of life was a lot lower but there are psychological benefits to this simplicity that our culture completely overlooks. As Oliver Burkeman explores in his book Four Thousand Weeks, the difference between the modern serf and the medieval one runs deeper than days worked. What it amounts to is a different relationship with time.

This transformation of our relationship to time happened somewhere in the past few centuries. Some, like sociologist Lewis Mumford, trace it back to the invention of the mechanical clock in the Middle Ages by monks looking to pray more consistently. Others attribute it to the Industrial Revolution and the urbanisation of the developed world. This change is best illustrated through a distinction between two ways of interacting with time. Let’s call one the intrinsic mode and the second the instrumental mode.

In the intrinsic mode we are motivated by things for their own sake; in the instrumental mode we are motivated to do things because of what they lead to; we don’t do them because they are inherently fun or meaningful but because of some benefit they’ll bring us in future.

No society has ever lived entirely in one mode or the other. You don’t boil the kettle or bring your clothes to a dry cleaner because it’s intrinsically enjoyable. You do it because you want a cup of tea or some clean clothes. With instrumentalisation we see things as valuable for what they lead to. The activity is a sacrifice now for a payoff in the future.

On the other hand think of hobbies. And we’re not talking about the kind of hobby which is or at some stage will become a side hustle. I’m talking about old-fashioned embarrassing hobbies. I’m talking about Rod Stewart spending three decades on a model train city. I’m talking about the people out there who crotchet and garden and make steam engines not because they plan on selling them or because the end product will win them some great admiration. I’m talking about hobbies that are done for love. Pure and simple.

The hobby is an exception in modern life. The difference between us citizens of modern life in comparison with the vast majority of our peers throughout history is that the majority of our lives are victims of instrumentalisation.

Even socialising has fallen prey to this trend. Once upon a time you hung out with your friends because it was intrinsically enjoyable but even something as simple as this has been colonised by the psychopathology of social media. As Bo Burnham put it in Inside:

The outside world, the non-digital world, is merely a theatrical space in which one stages and records content for the much more real, much more vital digital space. One should only engage with the outside world as one engages with a coal mine. Suit up, gather what is needed, and return to the surface.

So it’s not enough that instrumentalisation had conquered our work lives, it has now taken over our personal lives as well.

It’s not hard to connect this colonisation of instrumentalisation and the mainstreaming of Nihilism not to mention the mental health crisis and the meaning crisis. Intrinsic activities are inherently meaningful. When you’re having fun you don’t ask why. It’s only when everything you do is for some vague distant future that never arrives that you begin to question what the point of anything is.

The transformation of our relationship with time has brought humanity closer to greatness. We are moving out to the stars we are giving birth to a whole new type of being with AI we have all these shiny gadgets and cool holidays. We are closer to Nietzsche’s goal of the Übermensch. And we have never been so miserable.

Nobody is spared. The rich are probably even more damaged than the rest of us; they got where they are by being great at instrumentalisation. Unlike the Medieval or Ancient aristocracies, the modern elite the bourgeois capitalist doesn’t see work as beneath them as undignified. This couldn’t be further from the truth. They’re even further gone than the rest of us.

Conclusion

The narrative about our modern utopia is trash. Our quality of life has never been so good and our mental health so bad. The question is: why. If the trend of increasing quality of life is coupled to an impoverished internal life then we’ve got a major problem.

But maybe it’s a matter of metrics. The philosophy of modern times so far has been materialism. Materialism sees life in terms of its outer appearance. And so a person with a long span of life and a washing machine looks a lot happier to a materialist than a peasant in a hovel. By the metrics of materialism modernity has been a major success.

And so, what if we shift our metrics towards the phenomenological domain — that is to say what if we measure the good life by the internal state rather than the external one? There are a lot of signs that the materialist domination of our worldview may be waning and we are beginning to appreciate the value of the internal even though it is still a tricky domain to measure.

If so, then we needn’t become reactionaries looking to get back to the Middle Ages but reformers of modernity who are looking to turn the great machine of optimising modernity in the direction of the good life.

It’s hard to believe that a world whose entire identity is based on GDP can make this shift but it’s not outside the bounds of imagination. And so that’s the silver lining we can hope for.

”They were poor, undernourished, cold, fearful and dead — usually following some agony — before their fortieth birthdays. After a lifetime of work their most expensive possession might have been a cow, a goat, or a pot. Famine had never been far away and diseases had been rife; among the most common were rickets, ulcers, tuberculosis, leprosy, abscesses, gangerene, tumours and cankers.”

This is the story that we moderns tell ourselves about the Middle Ages. It fits well with our story about Progress — that things were worse in the past and they keep on getting better. Science and technology have stirred humanity from their sleep of ignorance and misery.

But this isn’t the only story that can be told about the Middle Ages (though it might be the most convenient). There’s another story we can tell about this time and it’s a story that needs to be told because if the story about Progress were true, then the world would want to have been a very very shitty place in the past.

In this instalment we are going to tell this forgotten story of the Middle Ages and what it is that modern society has forgotten. Not to spoil the ending too much but what we’ve forgotten is the meaning of life and how to live it; what we’ve forgotten is the lost art of leisure.

Modern Times

But before we tell the forgotten story, let’s remind ourselves of why we might need another story. After all if you’ve been reading the propaganda of the techno-optimists you might be a little bit baffled. Aren’t things getting better?

Never has there been less poverty, less starvation, less infant mortality and a higher quality of life. This is the story that fits well with de Botton’s quote from the start of the article on the misery of the Middle Ages.

But there’s also a dark side to modern life; as we’ve discussed many times on The Living Philosophy, for every step forward in material well-being we have taken one down into the pits of psychological hell.

In his book Authentic Happiness the former head of the American Psychological Association Martin Seligman outlined the paradox: in the 40 years before the publishing of that book in 2002 the prevalence of depression had increased ten times over and the mean age of your average person’s first depressive episode had come down from 29.5 years to 14.5 years old. The paradox lies in the fact that quality of life improved more in those forty years than perhaps any other time in history.

Fast forward fifteen years and Jonathan Haidt explores the evolution of this trend with social media factored in: self-harm, depression and suicide have skyrocketed among young teens. He correlates this with the emergence of social media but if we look deeper in the data we see that social media has only amplified an already underlying trend. It’s one greater step forward in technology and one giant leap into the depths of psychological Hell.

So it’s reasonable to suppose that while life has unarguably improved in many dimensions it hasn’t improved in every way and we might want to explore possibilities for why that might be so that we can improve things further.

A reasonable way of holding these two stories together is to say that technological progress has improved the external side of life. We have smartphones, electric cars and washing machines. This is good. But it has not improved the internal side of life. So two things are true: we live better lives by any external measure and we are more miserable by any internal measure.

The Other Story

So with that minor shade of doubt cast on the narrative of progress, let’s revisit our Medieval ancestors. Between all the dying from famine and horrible diseases, the people of the Middle Ages found some time to live their lives and to be honest it sounds like we could learn a few things.

And we’re not talking about the knights, dukes and kings here who obviously would have had a decent quality of life as the benefactors of the gross inequality of the times. We’re talking about the people at the bottom of the European hierarchy — the serfs and the peasants.

You see these poor folk had something we have lost — they had lives. Work was still something you did because it was necessary. Leisure was still the rule of life.

According to historians like Gregory Clark and Nora Ritchie, the average country dweller in the 16th century worked somewhere between 150 and 180 days a year. And it’s worth remembering here that the vast majority of people were country dwellers — even at the start of the 19th century 90% of people still lived on farms (a number which had dropped to less than 1% by the 21st century).

There were religious holidays and saints’ days to be celebrating not to mention multiple-day-long village festivals called “ales” to mark major events like weddings, funerals, the harvest and even lambing season. For every bout of work there was a call for a bout of community relaxation.

And on those days when they did finally get to work it wasn’t exactly the opening bell at Wall Street. Here’s how the Bishop of Durham described the work ethic of the peasant in the 1570s:

”The laboring man will take his rest long in the morning; a good piece of the day is spent afore he comes at his work. Then he must have his breakfast, though he have not earned it, at his accustomed hour, else there is grudging and murmuring […] At noon he must have his sleeping time, then his bever in the afternoon, which spendeth a great part of the day.”

For all the technological and medical backwardness of the Middle Ages there was still a sense in which their lives made sense. For the Medieval peasant work was still something you did because it was necessary. You worked today so you had shelter and food tomorrow.

They worked one day a week on the lord’s land which supposedly bought them protection. There was no saving for twenty years so their kid could go to a prestigious university; there was no saving forty years for a retirement where they could finally stop working; they had no thirty-year mortgages nor were they saddled by student debt or any debt. These are all the domain of the modern serf.

It’s obvious to everyone that the Medieval peasant’s quality of life was a lot lower but there are psychological benefits to this simplicity that our culture completely overlooks. As Oliver Burkeman explores in his book Four Thousand Weeks, the difference between the modern serf and the medieval one runs deeper than days worked. What it amounts to is a different relationship with time.

This transformation of our relationship to time happened somewhere in the past few centuries. Some, like sociologist Lewis Mumford, trace it back to the invention of the mechanical clock in the Middle Ages by monks looking to pray more consistently. Others attribute it to the Industrial Revolution and the urbanisation of the developed world. This change is best illustrated through a distinction between two ways of interacting with time. Let’s call one the intrinsic mode and the second the instrumental mode.

In the intrinsic mode we are motivated by things for their own sake; in the instrumental mode we are motivated to do things because of what they lead to; we don’t do them because they are inherently fun or meaningful but because of some benefit they’ll bring us in future.

No society has ever lived entirely in one mode or the other. You don’t boil the kettle or bring your clothes to a dry cleaner because it’s intrinsically enjoyable. You do it because you want a cup of tea or some clean clothes. With instrumentalisation we see things as valuable for what they lead to. The activity is a sacrifice now for a payoff in the future.

On the other hand think of hobbies. And we’re not talking about the kind of hobby which is or at some stage will become a side hustle. I’m talking about old-fashioned embarrassing hobbies. I’m talking about Rod Stewart spending three decades on a model train city. I’m talking about the people out there who crotchet and garden and make steam engines not because they plan on selling them or because the end product will win them some great admiration. I’m talking about hobbies that are done for love. Pure and simple.

The hobby is an exception in modern life. The difference between us citizens of modern life in comparison with the vast majority of our peers throughout history is that the majority of our lives are victims of instrumentalisation.

Even socialising has fallen prey to this trend. Once upon a time you hung out with your friends because it was intrinsically enjoyable but even something as simple as this has been colonised by the psychopathology of social media. As Bo Burnham put it in Inside:

The outside world, the non-digital world, is merely a theatrical space in which one stages and records content for the much more real, much more vital digital space. One should only engage with the outside world as one engages with a coal mine. Suit up, gather what is needed, and return to the surface.

So it’s not enough that instrumentalisation had conquered our work lives, it has now taken over our personal lives as well.

It’s not hard to connect this colonisation of instrumentalisation and the mainstreaming of Nihilism not to mention the mental health crisis and the meaning crisis. Intrinsic activities are inherently meaningful. When you’re having fun you don’t ask why. It’s only when everything you do is for some vague distant future that never arrives that you begin to question what the point of anything is.

The transformation of our relationship with time has brought humanity closer to greatness. We are moving out to the stars we are giving birth to a whole new type of being with AI we have all these shiny gadgets and cool holidays. We are closer to Nietzsche’s goal of the Übermensch. And we have never been so miserable.

Nobody is spared. The rich are probably even more damaged than the rest of us; they got where they are by being great at instrumentalisation. Unlike the Medieval or Ancient aristocracies, the modern elite the bourgeois capitalist doesn’t see work as beneath them as undignified. This couldn’t be further from the truth. They’re even further gone than the rest of us.

Conclusion

The narrative about our modern utopia is trash. Our quality of life has never been so good and our mental health so bad. The question is: why. If the trend of increasing quality of life is coupled to an impoverished internal life then we’ve got a major problem.

But maybe it’s a matter of metrics. The philosophy of modern times so far has been materialism. Materialism sees life in terms of its outer appearance. And so a person with a long span of life and a washing machine looks a lot happier to a materialist than a peasant in a hovel. By the metrics of materialism modernity has been a major success.

And so, what if we shift our metrics towards the phenomenological domain — that is to say what if we measure the good life by the internal state rather than the external one? There are a lot of signs that the materialist domination of our worldview may be waning and we are beginning to appreciate the value of the internal even though it is still a tricky domain to measure.

If so, then we needn’t become reactionaries looking to get back to the Middle Ages but reformers of modernity who are looking to turn the great machine of optimising modernity in the direction of the good life.

It’s hard to believe that a world whose entire identity is based on GDP can make this shift but it’s not outside the bounds of imagination. And so that’s the silver lining we can hope for.