🛠️ A System

Donnella Meadows on what makes a system

Names for concept: a system

Origin of Concept: Systems Thinking

Where it’s popular: Systems Thinking, Metamodernism, Integral Theory, Sensemaking

Useful for: understanding Systems

“A system is an interconnected set of elements that is coherently organized in a way that achieves something.” (Meadows 2009:11)

This week’s Philosopher’s Toolkit may become part of a theme. This is ripped right from our book club reading of Donella Meadows’ Thinking in Systems. On the one hand, this is a useful concept to have in your back pocket at any time when looking at anything from a subculture to an economy to your flossing routine (or lack thereof).

But it’s also going to make our book club a whole lot easier to navigate. I remember why I stopped reading Meadows’ book a decade ago now: I got overloaded with concepts, decided I needed to give it a more attentive reading and then, as Frost would say, “way leads onto way” and I never did return. Until now.

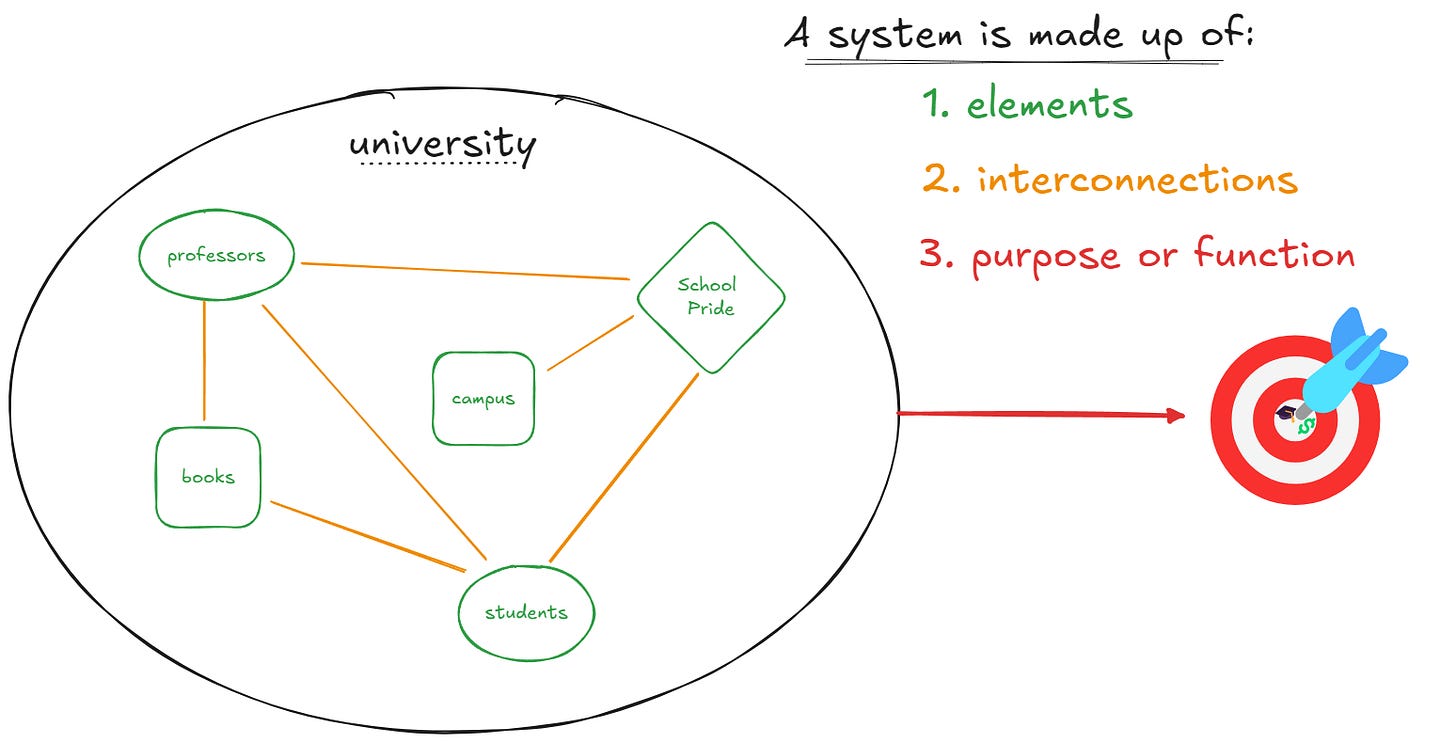

So, throat clearing complete, let’s dig in. What is a system? Well, any system, Meadows tells us, has three components:

Elements

Interconnections

Function or Purpose

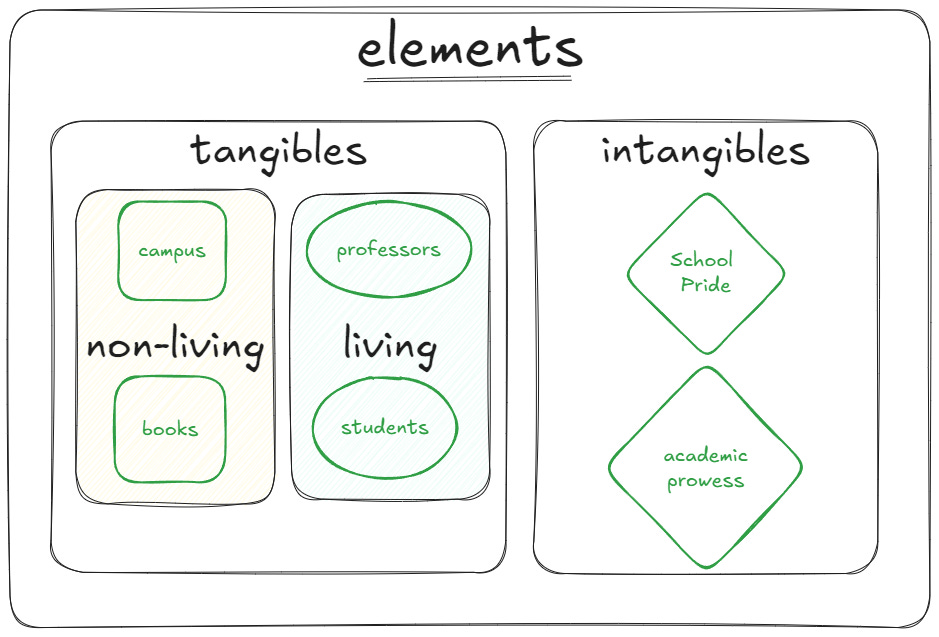

1. Elements

The elements in a system are the things. They’re the pieces of the system that you can point to. In the system of a forest, we have the trees, the soil, the mycelial network, the moss, the birds, the animals, the streams etc. As you can see, the elements of a system can be both living and non-living.

When it comes to human systems, we can see that elements aren’t even necessarily tangible. In the system of a university, as well as students, administrators, buildings and books, you have intangibles like school pride and academic prowess.

2. Interconnections

If elements are like the nodes in a network, the interconnections are the links (or “edges”) that join them together. There are two types of interconnections:

Physical flows: interconnections can be physical flows like water flowing through the xylem of the tree, or students flowing through the university's campus.

Informational flows: they can also be informational flows. In the tree example, we can think of the drop in pressure in water-carrying vessels signals the roots to take in more water when leaves lose water on a sunny day. Meanwhile, in the university system, we can think of a host of informational interconnections: the standards for admission, the requirements for degrees, the examinations and grades, the budgets and money flows, the gossip, and the education itself

3. Function or Purpose

The third component of a system is a function or a purpose. As you can see, we have two terms here:

Function: generally used for nonhuman systems

Purpose: generally used for human systems. Though as Meadows notes, “the distinction is not absolute, since so many systems have both human and nonhuman elements” (Meadows 2009:15)

This distinction confused me a bit, but I think I've figured it out: when a system contains humans as an element, we will usually use the word purpose: universities have a purpose, a football team has a purpose, the economy has a purpose.

But when a system doesn't contain humans, they are spoken of using the language of functions, even if they contain living beings. So we can speak of the function of an air-conditioning system, the function of your digestive system, the function of a plant.

I guess the idea is that the more predictable and mechanic the behaviour of a system is, the more we use the language of functions? I’m not wild about this distinction, but there you have it.

Anyway, the function/purpose of the system is its telos — the end it is trying to bring about. Let’s look again at Meadows’ definition of a system quoted at the start of the article:

“A system is an interconnected set of elements that is coherently organized in a way that achieves something.” (Meadows 2009:11)

So the function/purpose of a system is the “something” the system seeks to achieve. Let’s look at a few examples. In our tree example, we can quote Meadows talking about plants:

“One function of a plant is to bear seeds and create more plants.” (Meadows 2009:15)

In the university example:

“The purpose of a university is to discover and preserve knowledge and pass it on to new generations” (Meadows 2009:15)

Reflections

This is a neat little concept. I’m with her as far as elements and interconnections go, but when it comes to the function/purpose piece, I’m not sold. And it’s not just because of the distinction between function and purpose. This ties in with a broader discomfort I have with entelechy and teleology (see the second instalment from our previous book club on Ken Wilber’s Theory of Everything. See also my first appearance on Brendan Graham Dempsey’s Metamodern Spirituality).

I’ve been mulling over this a bit. We do design systems with an end in mind. And we can speak about certain goals of an organism like survival and reproduction. I have talked previously about the metrics we optimise for and their danger (see the episode on beauty). I’ve also been meaning to write about Goodhart’s Law, which is the idea that “when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

All of which to say, I’m on board for integrating the language of metrics and goals into this. When we’re solving the climate crisis, we’re not talking about ecosystem preservation or forestation, we’re talking about CO2 in the atmosphere. And when we talk about the economy, we are focused on GDP as the measure. These metrics impact the nature of the system. That’s an important thing to talk about.

I think then, my discomfort is less from the theoretical role that this third component is playing than with the framing of it in teleological terms as “functions” and “purposes”. It seems to me that this smuggles in some ideology, and I am not here for it.

I hope this was helpful for those of you reading along with the book club. I’ve finished reading next week’s chapter. There are more key concepts that could do with this treatment, and so this will undoubtedly become a theme in future instalments.

Bibliography:

Meadows, D. 2009. Thinking in Systems London: Earthscan

This has been another instalment of The Philosopher’s Toolkit. For an introduction to the series see here (substack) here (Patreon). It was inspired by two things: Deleuze’s definition of philosophy as “forming, inventing and fabricating concepts” and the old saying that “if all you have is a hammer, every problem begins to look like a nail”. The aim of the Philosopher’s Toolkit is to give you more tools for interacting with the world.

Thank you for highlighting that function and purpose it was what stumped me when I first come upon it a couple of years ago and did a similar put down and now I'm picked up

Great takeaways! “Good hart’s Law”-“when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” Could you elaborate for us? Does this affect the maxim “to begin with the end in mind”? And cautions us against preconceived assured outcomes?

Thank you. This was very interesting to read.