🛠️Paradigm, A Brief Guide

I'm still feeling my way around this Philosopher's Toolkit idea. I'm seeing it a little like lego: these are the building blocks of philosophies. I have this sense that in getting down to these building blocks, the possibility of building new wholes becomes possible. It's an experiment. If nothing else, it's a good resource for these concepts in future. Also, I'm going to try illustrating ideas more. I'm finding visualising the learning makes it more concrete for me and makes the whole thing land more easily on the eye. I'm flirting with the thought of building out a visual dictionary of concepts to be linked to in future articles — so, like lego, we can build something bigger together.

Category: Metacartography; Fundamentals

Names for concept: Paradigm

Thinker of Origin: Thomas Kuhn

School of Origin: Philosophy of Science

Where it’s popular: everywhere from Business Gurus talking about Paradigm Shifts to the history of ideas, Philosophy of Science, Sensemaking, Critical Theory and beyond

Why it matters:

Gives us a more accurate map of how human belief systems work.

Shows we are not rational animals but social animals and this is a better lens for understanding human endeavours.

In his (quite literally) Paradigm-defining work, Thomas Kuhn made an argument that had all the Scientism adherents spitting their dummies out. That work, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, has gone on to become one of the most referenced academic works in history and one of the most influential and controversial books of the 20th century. Its release in 1962 triggered a hornet’s nest of activity in response. The accusation of relativist was thrown about with some weight (had it been a decade later, the word Postmodernist would undoubtedly have been the insult of choice).

The traditional myth of Scientism has humanity emerging from the mire of ignorance somewhere around the 16th century and since then our proximity to truth has been narrowing daily as the giant heap of scientific knowledge piles up. It’s a story of linear accumulation in which scientists driven by noble triumvirate of curiosity, reason and intellect have been winning the war against ignorance.

Kuhn’s narrative is a little less flattering.

Having studied the history of science, Kuhn was struck by the contrast between the reality of scientific history and the narrative he and every other student of the sciences is given in their undergraduate courses and textbooks. Instead of seeing science as a logical process of epistemic rigour, Kuhn’s model of science is more sociological and evolutionary. Scientists are less heroic warriors of truth and more puzzle-solvers — taking already established knowledge and trying to move it forward one step.

Like all puzzle-solvers, scientists work within narrow confines. The work of science is like solving a crossword — you are already working within a given structure, and it is your job to find the answers that fit within that structure. If you’re trying to solve a Rubik’s cube or a chess puzzle, there is a whole cluster of pre-determined implications. The solution for a start: with a Rubik’s cube, your goal is to get each piece on a side with other pieces of the same colour, with the chess puzzle, you are usually trying to find the checkmate. But it’s not just the solution that’s determined, but the method for arriving at the solution. You are not supposed to solve the Rubik’s cube as my brother did when we were young: by firing it off a wall and putting it back together in the right way. With the chess puzzle, you must operate within the standard rules of chess — you can’t declare the rooks’ new ability to leapfrog pawns.

This is what Kuhn means by the term paradigm: it’s the structural container within which scientists work.

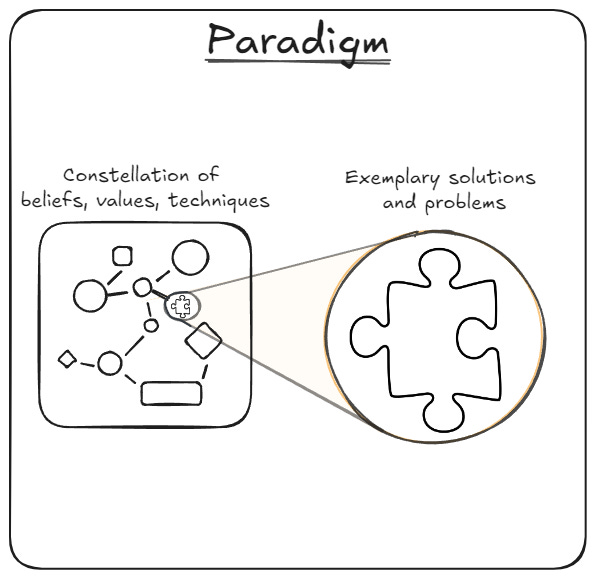

“the term ‘paradigm’ is used in two different senses. On the one hand, it stands for the entire constellation of beliefs, values, techniques, and so on shared by the members of a given community. On the other, it denotes one sort of element in that constellation, the concrete puzzle-solutions which, employed as models or examples, can replace explicit rules as a basis for the solution of the remaining puzzles of normal science.” (p.175)

So we have two main pieces.

The first is the constellation of beliefs, values and practices the community share — Kuhn calls this the sociological element.

The second is a subset of this — it’s the example set by the paradigm creator whether that’s Newton, Darwin or Lavoisier. Their work sets an example for what a good solution looks like. It also acts like a compass, pointing the paradigm’s scientists towards certain types of problems that need solving. It tells them how to do their work and it tells them what that work should be.

To learn more about paradigms, check out the video on it from a couple of years back here. And a second one that goes more in-depth about Kuhn's theory of science's evolution here.

I love this idea, James. I’m a visual learner and this makes total sense to me. (And by the way, my son at age 4 “solved” the rubics cube, after he discovered that the colors on the squares peeled off! That’s one way to solve that puzzle. 😆).