There has never been more hate in the world than there is today. It sounds like an exaggeration but when we study the term ressentiment it becomes obvious that because of our modern value system there has never been so much hate to go around. Negative as this sounds, this very same potential for hate is also the birth canal of all our progress including technologically and economically but also our social progress such as the abolishing of slavery, the freedom of all to vote and the possibility of social mobility. The modern dream of freedom and democracy casts a dark shadow; that dark shadow is ressentiment.

Friedrich Nietzsche, who first developed the term in his 1887 work On the Genealogy of Morals saw ressentiment as the root cause of Slave Morality and the Ascetic Ideal.

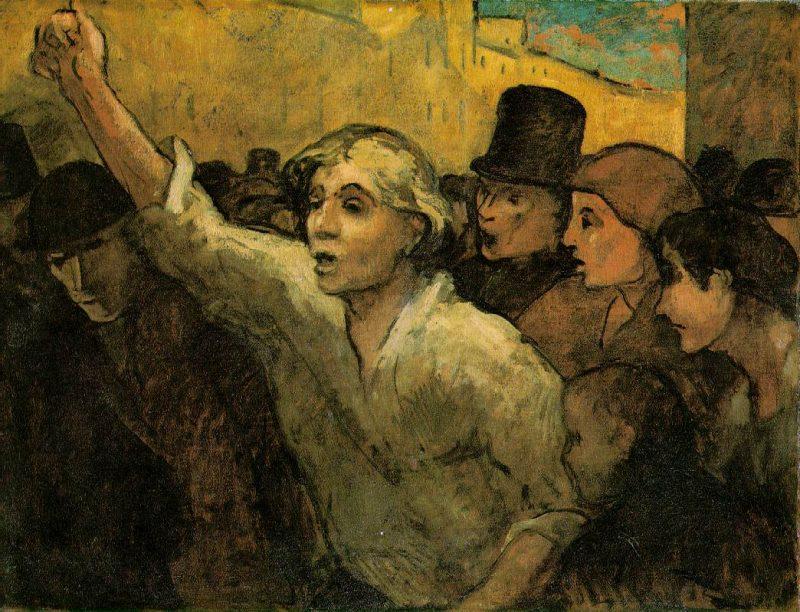

Max Scheler’s 1915 book Ressentiment took Nietzsche’s analysis further. Scheler challenged Nietzsche’s claim that ressentiment was the basis of Christianity and instead argued that the modern bourgeois values of equality and liberty — and their political manifestation democracy — have created a monstrous world of ressentiment. Scheler described the French Revolution as a “massive explosion of ressentiment”.

More recent scholars have developed this revolutionary component of ressentiment and challenged Nietzsche and Scheler’s conceptions of ressentiment as a passive emotion.

Instead they argue ressentiment is the “very content of revolutions”. It is an active force in society — the driving force behind all social change.

Ressentiment is the fundamental emotion of the Culture Wars and even more than that it is the fundamental emotion of modern times. It is an inevitable part of democracy — baked as it is into the idea of equality. And as much as it is an essential component of modernity’s favourite governance system, it is also the greatest threat to democracy — a trend we are seeing playing itself out in an increasingly unstable spiralling out of control that we are seeing in the 21st century. It is the emotional frequency of uncontained liminality.

But what is ressentiment?

Resentment and Ressentiment

Ressentiment is an emotion in the resentment family. And so before exploring ressentiment we must first explore resentment.

By resentment here we mean a sense of being wronged – of being insulted, offended or deprived unjustly. It is an emotional alarm bell signalling that our self-esteem has been attacked. It’s important to note the moral undertone here. The great 20th century philosopher of justice John Rawls suggests that resentment (and by extension ressentiment) assumes equality and hence is tied to our justice complex.

Another key distinction is between resentment and indignation. In the case of resentment the victim is ourselves; in the case of indignation the victim is somebody else. Both are moral emotions but resentment and its offspring aren’t merely morally scandalous but personal experiences of attack.

So resentment then is a moral emotion in which we are the victims. But what separates resentment from ressentiment? In their article Resentment and Ressentiment Meltzer and Musolf explore the various definitions of ressentiment in the literature and they identify two key features of the term that distinguish it from resentment:

- the chronic ongoing character of the emotional experience

- the powerlessness of the individual experiencing the emotion to take retaliatory action against the sources of their emotional storm Resentment then is the fruit of sporadic, isolated injustices whereas ressentiment is related to ongoing, lasting injustices.

Something can happen today that makes you feel resentful but you might forget it tomorrow and never think of it again or only rarely. That would be resentment. You have been wronged but it’s far from a defining theme of your life.

But when the injustice is something that you engage with daily and are powerless to affect then we’re talking about a different animal. We’ve moved from resentment to ressentiment. Whenever we feel like a David fighting a Goliath — when we feel like a bug being tortured by a giant — then we have entered the realm of ressentiment. If you feel like the Patriarchy dominates how you live your life or if you feel like liberals and their Social Justice Movement are polluting schools and destroying the culture then you’re in the throes of ressentiment.

And on that note, having carved out the emotional territory of Ressentiment, let’s look at what Nietzsche has to say about it.

Nietzschean Ressentiment

By the Waters of Babylon by Evelyn de Morgan (image via Wikimedia: Public Domain)

In his 1887 work On the Genealogy of Morals Nietzsche gives us the first systematic account of ressentiment and its role in world history. This bitter child of resentment is key to his analysis of what he calls Slave Morality especially in its Judeo-Christian form but also in the form of egalitarian-socialistic ideologies.

Ressentiment is the very foundation of Slave Morality. In the first essay of the Genealogy Nietzsche writes:

”in order to exist, slave morality always first needs a hostile external world; it needs, physiologically speaking, external stimuli in order to act at all — its action is fundamentally reaction.”

Thus Slave Morality requires the trigger of the ressentiment-inducing injustice in order to come into being. And with that foundation of ressentiment in place the pressure of this pain can turn the darkness into diamonds. Nietzsche writes that:

”The slave revolt in morality begins when ressentiment itself becomes creative and gives birth to values.”

There are plenty of historical examples we can use to give substance to Nietzsche’s account. We could look at the birth of Judaism out of the destruction of Jerusalem and her temple by the Babylonians and the forced exile in Babylon of the majority of the upper class of the Jewish kingdom of Judah. This event which shattered the power of these people led to a deep deep ressentiment which we can see in the famous Psalm 137 written by the prophet Ezekiel in exile in Babylon. He writes:

”O Daughter of Babylon, doomed to destruction, blessed is he who repays you as you have done to us. Blessed is he who seizes your infants and dashes them against the rocks.“

But there wasn’t simply ressentiment. This was the end of the worship of idolatry among the Jewish people and when the religious identity crystallised. As one Biblical scholar has put it:

“The exile is the watershed. With the exile, the religion of Israel comes to an end and Judaism begins.”

With the yoke of Babylon upon the Jewish people the ressentiment that this caused gave birth to a revaluation of values — to the Slave Morality of Judaism as Nietzsche would have it.

We could also look at the birth of the Socialist and Communist movements in the late 18th and 19th centuries out of the horrendous exploitation of the newly emerged working class in the factories of the Industrial Revolution. The great ressentiment of this time led to a new birth of Slave Morality which threatened to transform the society.

This movement too had its prophets like Marx and Engels, Proudhon and Bakunin. But with the rise of the Trade Union movement the mass energy of this ressentiment faded in the West as the workers were given fairer compensation and better working conditions.

In both of these cases we have a group of people who are subjected to an enduring injustice. Out of this pressure cooker of ressentiment new narratives were born which gave meaning to the lives of these groups.

This is what Nietzsche really sees as going on in Slave Moralities. Given the blockage of their ability to revenge themselves in this world — either by the defeat of Babylon or dominance of the capitalist employers — the ressentimentful take their revenge in an imaginary world.

The Jewish people tell a story about their God and the meaning of what has happened as a punishment. This narrative keeps them as the chosen people of their God and gives a metaphysical meaning to everything that has transpired. Lacking the stomach for the material explanation of things they look to an imaginary world of Yahweh and his whims.

And in the case of the socialists and communists the other world is not a metaphysical one but it’s just as far off. These thinkers write about utopias that are to come. Marx, drawing on a Hegelian vision of a linear evolution throughout history, prophesies the inevitable rise of the proletarian people to bring about equality and an end to injustice in the world. This fervent faith in the historical inevitability of the revolution sustained Marx through a life of abject poverty and it has sustained many more since.

In both cases we see Nietzsche’s account of the ressentimentful creating another world in order to make this present one liveable. Ultimately these new narratives of the prophets of ressentiment are essentially Marx’s opium for the masses. He writes:

”This, I surmise, constitutes the actual physiological cause of ressentiment, vengefulness and the like: a desire to deaden pains by means of the affects.”

That is to say, that this Slave Morality kills the pain of our humiliation by creating a new narrative which empowers us. This ressentimentful narrative deadens our pain by making us feel special in our own story — by making us feel as if we are the truly higher status ones.

By leveraging this “other world” the slave gets their revenge. Where reality has denied them the true revenge of the deed, they compensate themselves with an imaginary revenge of Heaven and Hell or of Karma or Utopia depending on their belief system.

The lasting impression of Nietzsche’s account of ressentiment (and later Scheler’s too) is to see ressentiment as resulting in a sort of worldly resignation. The Slaves don’t take up arms against the masters. The Jewish people did nothing against the Babylonians; instead they had to wait for liberation at the hands of the Persian army who defeated the Babylonians. All the ressentimentful could do was create their Slave Morality which inverted the values of worldliness into their metaphysical valuations in which the lamb is better than the eagle.

But as the history of modernity can well attest this is far from the case. Ressentiment doesn’t merely give birth to delusions of grandeur that serve merely to accommodate us to our unfortunate reality. In the century since Nietzsche and Scheler the power of ressentiment to impact this world has become conscious in scholars of ressentiment.

Revolutionary Ressentiment

Ressentiment and radical politics seem to be the same phenomenon viewed from the inside and the outside respectively. Every radical political group from our 21st century leftists and populists to the 20th century’s communists and fascists are driven by ressentiment. It is not a question of left or right but of radical or moderate.

The defining theme of radical politics both of the far left and the far right is a mistrust of the Establishment. On the right we can think of Trump’s language of “draining the swamp”. On the left we can think of the critiques of capitalism or in recent decades the growing emphasis on systemic racism and the patriarchy.

All this radicalism is the political fingerprint of ressentiment. As Frederic Jameson put it: “ressentiment is the very content of revolution”. And revolution is what radicals are calling for. This history of radicalism and revolution is a history of ressentiment.

When the American colonists felt the injustice of their treatment at the hands of the British they were experiencing ressentiment. When the middle and lower classes of French society were told to eat cake by the monarchy as they struggled for bread they were experiencing ressentiment. In the months after the 2020 election when Trump protesters were furious and trying to “Stop the Steal” they were filled with ressentiment. And when Black Lives Matter protestors took to the streets to protest the death of George Floyd they too were overflowing with ressentiment. The same goes for the Civil Rights Movement, the Proud Boys, the Black Panthers, the Arab Spring and Extinction Rebellion.

The furnace of hatred burns very hot and Nietzsche was mistaken in his belief that ressentiment only leads to a revaluation of this world. Indeed he himself noted that:

”the last political noblesse in Europe, that of the French seventeenth and eighteenth century, collapsed beneath the popular instincts of ressentiment”

Or as Scheler put it the French Revolution was “an enormous explosion of ressentiment”.

Jameson is not alone in amplifying this theme. Historian Hippolyte Taine looked to explain revolutions in terms of ressentiment in his work and Folger claims that revolutionary ideologies can create ressentiment.

Ressentiment in the 21st Century

The relevance of all this to our current historical moment with the so-called Culture Wars is undeniable. It seems that we need to hate and be angry in order to bring about mass change. Only by being set on fire in this way can we find the motivation to fight for change.

Our gaping wounds of ressentiment are only fuelled by the mob-like nature of the libertarian wild west that is the internet and social media. This 21st century experience provides fertile ground for the two traits that make ressentiment out of resentment.

Firstly the experience of our complete inconsequence amid the billions of posts on social media can leave us with the sense of impotence that is essential for ressentiment. And secondly the outrage porn of the social media algorithms makes the condition chronic as it feeds us post after post which reinforces the ressentimentful narrative.

We need only look at the wave of ressentiment in the red ocean outside of America’s great urban centres that we’ve looked at in recent instalments of The Living Philosophy. This radical right wave of Populism — fuelled by the prophets of Fox News — feel a bitterness against the Rich Men North of Richmond and the well-educated SJWs who are trying to take over their country through the education system.

On the other side of the trenches the Social Justice Movement has whipped up cyclones of ressentiment over the systemic racism and sexism, transphobia and of course capitalism. From BLM to #MeToo we’ve seen ressentiment reaching a boiling point on the left.

Looking at these pressure cookers of radicalism, there can be no doubt about the power of ressentiment to bring about mass change. The seeming unassailability of the monolithic abstractions like “the Establishment”, ”the System” and “the State” have proven to be anything but unassailable. These towering Leviathans may seem impossible to nudge even an inch but with the ressentiment at scale that is the internet these Leviathans are under constant siege. The ressentiment of the mob is the defining force of the 21st century.

There are many more fruitful avenues we could explore on this theme of ressentiment. It is hard to resist mapping over ressentiment with our recent explorations of Liminality but we will leave that for a possible future article.

Another theme which we’ve unfortunately excluded from this instalment is the connections between ressentiment and the modern darlings of equality and democracy. This is a theme we will certainly be returning to in a future article as we explore the ressentimentful instability that is inherent in Democracy and which goes to explain why the modern era more than any other has been characterised by ressentiment.

There has never been more hate in the world than there is today. It sounds like an exaggeration but when we study the term ressentiment it becomes obvious that because of our modern value system there has never been so much hate to go around. Negative as this sounds, this very same potential for hate is also the birth canal of all our progress including technologically and economically but also our social progress such as the abolishing of slavery, the freedom of all to vote and the possibility of social mobility. The modern dream of freedom and democracy casts a dark shadow; that dark shadow is ressentiment.

Friedrich Nietzsche, who first developed the term in his 1887 work On the Genealogy of Morals saw ressentiment as the root cause of Slave Morality and the Ascetic Ideal.

Max Scheler’s 1915 book Ressentiment took Nietzsche’s analysis further. Scheler challenged Nietzsche’s claim that ressentiment was the basis of Christianity and instead argued that the modern bourgeois values of equality and liberty — and their political manifestation democracy — have created a monstrous world of ressentiment. Scheler described the French Revolution as a “massive explosion of ressentiment”.

More recent scholars have developed this revolutionary component of ressentiment and challenged Nietzsche and Scheler’s conceptions of ressentiment as a passive emotion.

Instead they argue ressentiment is the “very content of revolutions”. It is an active force in society — the driving force behind all social change.

Ressentiment is the fundamental emotion of the Culture Wars and even more than that it is the fundamental emotion of modern times. It is an inevitable part of democracy — baked as it is into the idea of equality. And as much as it is an essential component of modernity’s favourite governance system, it is also the greatest threat to democracy — a trend we are seeing playing itself out in an increasingly unstable spiralling out of control that we are seeing in the 21st century. It is the emotional frequency of uncontained liminality.

But what is ressentiment?

Resentment and Ressentiment

Ressentiment is an emotion in the resentment family. And so before exploring ressentiment we must first explore resentment.

By resentment here we mean a sense of being wronged – of being insulted, offended or deprived unjustly. It is an emotional alarm bell signalling that our self-esteem has been attacked. It’s important to note the moral undertone here. The great 20th century philosopher of justice John Rawls suggests that resentment (and by extension ressentiment) assumes equality and hence is tied to our justice complex.

Another key distinction is between resentment and indignation. In the case of resentment the victim is ourselves; in the case of indignation the victim is somebody else. Both are moral emotions but resentment and its offspring aren’t merely morally scandalous but personal experiences of attack.

So resentment then is a moral emotion in which we are the victims. But what separates resentment from ressentiment? In their article Resentment and Ressentiment Meltzer and Musolf explore the various definitions of ressentiment in the literature and they identify two key features of the term that distinguish it from resentment:

- the chronic ongoing character of the emotional experience

- the powerlessness of the individual experiencing the emotion to take retaliatory action against the sources of their emotional storm Resentment then is the fruit of sporadic, isolated injustices whereas ressentiment is related to ongoing, lasting injustices.

Something can happen today that makes you feel resentful but you might forget it tomorrow and never think of it again or only rarely. That would be resentment. You have been wronged but it’s far from a defining theme of your life.

But when the injustice is something that you engage with daily and are powerless to affect then we’re talking about a different animal. We’ve moved from resentment to ressentiment. Whenever we feel like a David fighting a Goliath — when we feel like a bug being tortured by a giant — then we have entered the realm of ressentiment. If you feel like the Patriarchy dominates how you live your life or if you feel like liberals and their Social Justice Movement are polluting schools and destroying the culture then you’re in the throes of ressentiment.

And on that note, having carved out the emotional territory of Ressentiment, let’s look at what Nietzsche has to say about it.

Nietzschean Ressentiment

By the Waters of Babylon by Evelyn de Morgan (image via Wikimedia: Public Domain)

In his 1887 work On the Genealogy of Morals Nietzsche gives us the first systematic account of ressentiment and its role in world history. This bitter child of resentment is key to his analysis of what he calls Slave Morality especially in its Judeo-Christian form but also in the form of egalitarian-socialistic ideologies.

Ressentiment is the very foundation of Slave Morality. In the first essay of the Genealogy Nietzsche writes:

”in order to exist, slave morality always first needs a hostile external world; it needs, physiologically speaking, external stimuli in order to act at all — its action is fundamentally reaction.”

Thus Slave Morality requires the trigger of the ressentiment-inducing injustice in order to come into being. And with that foundation of ressentiment in place the pressure of this pain can turn the darkness into diamonds. Nietzsche writes that:

”The slave revolt in morality begins when ressentiment itself becomes creative and gives birth to values.”

There are plenty of historical examples we can use to give substance to Nietzsche’s account. We could look at the birth of Judaism out of the destruction of Jerusalem and her temple by the Babylonians and the forced exile in Babylon of the majority of the upper class of the Jewish kingdom of Judah. This event which shattered the power of these people led to a deep deep ressentiment which we can see in the famous Psalm 137 written by the prophet Ezekiel in exile in Babylon. He writes:

”O Daughter of Babylon, doomed to destruction, blessed is he who repays you as you have done to us. Blessed is he who seizes your infants and dashes them against the rocks.“

But there wasn’t simply ressentiment. This was the end of the worship of idolatry among the Jewish people and when the religious identity crystallised. As one Biblical scholar has put it:

“The exile is the watershed. With the exile, the religion of Israel comes to an end and Judaism begins.”

With the yoke of Babylon upon the Jewish people the ressentiment that this caused gave birth to a revaluation of values — to the Slave Morality of Judaism as Nietzsche would have it.

We could also look at the birth of the Socialist and Communist movements in the late 18th and 19th centuries out of the horrendous exploitation of the newly emerged working class in the factories of the Industrial Revolution. The great ressentiment of this time led to a new birth of Slave Morality which threatened to transform the society.

This movement too had its prophets like Marx and Engels, Proudhon and Bakunin. But with the rise of the Trade Union movement the mass energy of this ressentiment faded in the West as the workers were given fairer compensation and better working conditions.

In both of these cases we have a group of people who are subjected to an enduring injustice. Out of this pressure cooker of ressentiment new narratives were born which gave meaning to the lives of these groups.

This is what Nietzsche really sees as going on in Slave Moralities. Given the blockage of their ability to revenge themselves in this world — either by the defeat of Babylon or dominance of the capitalist employers — the ressentimentful take their revenge in an imaginary world.

The Jewish people tell a story about their God and the meaning of what has happened as a punishment. This narrative keeps them as the chosen people of their God and gives a metaphysical meaning to everything that has transpired. Lacking the stomach for the material explanation of things they look to an imaginary world of Yahweh and his whims.

And in the case of the socialists and communists the other world is not a metaphysical one but it’s just as far off. These thinkers write about utopias that are to come. Marx, drawing on a Hegelian vision of a linear evolution throughout history, prophesies the inevitable rise of the proletarian people to bring about equality and an end to injustice in the world. This fervent faith in the historical inevitability of the revolution sustained Marx through a life of abject poverty and it has sustained many more since.

In both cases we see Nietzsche’s account of the ressentimentful creating another world in order to make this present one liveable. Ultimately these new narratives of the prophets of ressentiment are essentially Marx’s opium for the masses. He writes:

”This, I surmise, constitutes the actual physiological cause of ressentiment, vengefulness and the like: a desire to deaden pains by means of the affects.”

That is to say, that this Slave Morality kills the pain of our humiliation by creating a new narrative which empowers us. This ressentimentful narrative deadens our pain by making us feel special in our own story — by making us feel as if we are the truly higher status ones.

By leveraging this “other world” the slave gets their revenge. Where reality has denied them the true revenge of the deed, they compensate themselves with an imaginary revenge of Heaven and Hell or of Karma or Utopia depending on their belief system.

The lasting impression of Nietzsche’s account of ressentiment (and later Scheler’s too) is to see ressentiment as resulting in a sort of worldly resignation. The Slaves don’t take up arms against the masters. The Jewish people did nothing against the Babylonians; instead they had to wait for liberation at the hands of the Persian army who defeated the Babylonians. All the ressentimentful could do was create their Slave Morality which inverted the values of worldliness into their metaphysical valuations in which the lamb is better than the eagle.

But as the history of modernity can well attest this is far from the case. Ressentiment doesn’t merely give birth to delusions of grandeur that serve merely to accommodate us to our unfortunate reality. In the century since Nietzsche and Scheler the power of ressentiment to impact this world has become conscious in scholars of ressentiment.

Revolutionary Ressentiment

Ressentiment and radical politics seem to be the same phenomenon viewed from the inside and the outside respectively. Every radical political group from our 21st century leftists and populists to the 20th century’s communists and fascists are driven by ressentiment. It is not a question of left or right but of radical or moderate.

The defining theme of radical politics both of the far left and the far right is a mistrust of the Establishment. On the right we can think of Trump’s language of “draining the swamp”. On the left we can think of the critiques of capitalism or in recent decades the growing emphasis on systemic racism and the patriarchy.

All this radicalism is the political fingerprint of ressentiment. As Frederic Jameson put it: “ressentiment is the very content of revolution”. And revolution is what radicals are calling for. This history of radicalism and revolution is a history of ressentiment.

When the American colonists felt the injustice of their treatment at the hands of the British they were experiencing ressentiment. When the middle and lower classes of French society were told to eat cake by the monarchy as they struggled for bread they were experiencing ressentiment. In the months after the 2020 election when Trump protesters were furious and trying to “Stop the Steal” they were filled with ressentiment. And when Black Lives Matter protestors took to the streets to protest the death of George Floyd they too were overflowing with ressentiment. The same goes for the Civil Rights Movement, the Proud Boys, the Black Panthers, the Arab Spring and Extinction Rebellion.

The furnace of hatred burns very hot and Nietzsche was mistaken in his belief that ressentiment only leads to a revaluation of this world. Indeed he himself noted that:

”the last political noblesse in Europe, that of the French seventeenth and eighteenth century, collapsed beneath the popular instincts of ressentiment”

Or as Scheler put it the French Revolution was “an enormous explosion of ressentiment”.

Jameson is not alone in amplifying this theme. Historian Hippolyte Taine looked to explain revolutions in terms of ressentiment in his work and Folger claims that revolutionary ideologies can create ressentiment.

Ressentiment in the 21st Century

The relevance of all this to our current historical moment with the so-called Culture Wars is undeniable. It seems that we need to hate and be angry in order to bring about mass change. Only by being set on fire in this way can we find the motivation to fight for change.

Our gaping wounds of ressentiment are only fuelled by the mob-like nature of the libertarian wild west that is the internet and social media. This 21st century experience provides fertile ground for the two traits that make ressentiment out of resentment.

Firstly the experience of our complete inconsequence amid the billions of posts on social media can leave us with the sense of impotence that is essential for ressentiment. And secondly the outrage porn of the social media algorithms makes the condition chronic as it feeds us post after post which reinforces the ressentimentful narrative.

We need only look at the wave of ressentiment in the red ocean outside of America’s great urban centres that we’ve looked at in recent instalments of The Living Philosophy. This radical right wave of Populism — fuelled by the prophets of Fox News — feel a bitterness against the Rich Men North of Richmond and the well-educated SJWs who are trying to take over their country through the education system.

On the other side of the trenches the Social Justice Movement has whipped up cyclones of ressentiment over the systemic racism and sexism, transphobia and of course capitalism. From BLM to #MeToo we’ve seen ressentiment reaching a boiling point on the left.

Looking at these pressure cookers of radicalism, there can be no doubt about the power of ressentiment to bring about mass change. The seeming unassailability of the monolithic abstractions like “the Establishment”, ”the System” and “the State” have proven to be anything but unassailable. These towering Leviathans may seem impossible to nudge even an inch but with the ressentiment at scale that is the internet these Leviathans are under constant siege. The ressentiment of the mob is the defining force of the 21st century.

There are many more fruitful avenues we could explore on this theme of ressentiment. It is hard to resist mapping over ressentiment with our recent explorations of Liminality but we will leave that for a possible future article.

Another theme which we’ve unfortunately excluded from this instalment is the connections between ressentiment and the modern darlings of equality and democracy. This is a theme we will certainly be returning to in a future article as we explore the ressentimentful instability that is inherent in Democracy and which goes to explain why the modern era more than any other has been characterised by ressentiment.

There has never been more hate in the world than there is today. It sounds like an exaggeration but when we study the term ressentiment it becomes obvious that because of our modern value system there has never been so much hate to go around. Negative as this sounds, this very same potential for hate is also the birth canal of all our progress including technologically and economically but also our social progress such as the abolishing of slavery, the freedom of all to vote and the possibility of social mobility. The modern dream of freedom and democracy casts a dark shadow; that dark shadow is ressentiment.

Friedrich Nietzsche, who first developed the term in his 1887 work On the Genealogy of Morals saw ressentiment as the root cause of Slave Morality and the Ascetic Ideal.

Max Scheler’s 1915 book Ressentiment took Nietzsche’s analysis further. Scheler challenged Nietzsche’s claim that ressentiment was the basis of Christianity and instead argued that the modern bourgeois values of equality and liberty — and their political manifestation democracy — have created a monstrous world of ressentiment. Scheler described the French Revolution as a “massive explosion of ressentiment”.

More recent scholars have developed this revolutionary component of ressentiment and challenged Nietzsche and Scheler’s conceptions of ressentiment as a passive emotion.

Instead they argue ressentiment is the “very content of revolutions”. It is an active force in society — the driving force behind all social change.

Ressentiment is the fundamental emotion of the Culture Wars and even more than that it is the fundamental emotion of modern times. It is an inevitable part of democracy — baked as it is into the idea of equality. And as much as it is an essential component of modernity’s favourite governance system, it is also the greatest threat to democracy — a trend we are seeing playing itself out in an increasingly unstable spiralling out of control that we are seeing in the 21st century. It is the emotional frequency of uncontained liminality.

But what is ressentiment?

Resentment and Ressentiment

Ressentiment is an emotion in the resentment family. And so before exploring ressentiment we must first explore resentment.

By resentment here we mean a sense of being wronged – of being insulted, offended or deprived unjustly. It is an emotional alarm bell signalling that our self-esteem has been attacked. It’s important to note the moral undertone here. The great 20th century philosopher of justice John Rawls suggests that resentment (and by extension ressentiment) assumes equality and hence is tied to our justice complex.

Another key distinction is between resentment and indignation. In the case of resentment the victim is ourselves; in the case of indignation the victim is somebody else. Both are moral emotions but resentment and its offspring aren’t merely morally scandalous but personal experiences of attack.

So resentment then is a moral emotion in which we are the victims. But what separates resentment from ressentiment? In their article Resentment and Ressentiment Meltzer and Musolf explore the various definitions of ressentiment in the literature and they identify two key features of the term that distinguish it from resentment:

- the chronic ongoing character of the emotional experience

- the powerlessness of the individual experiencing the emotion to take retaliatory action against the sources of their emotional storm Resentment then is the fruit of sporadic, isolated injustices whereas ressentiment is related to ongoing, lasting injustices.

Something can happen today that makes you feel resentful but you might forget it tomorrow and never think of it again or only rarely. That would be resentment. You have been wronged but it’s far from a defining theme of your life.

But when the injustice is something that you engage with daily and are powerless to affect then we’re talking about a different animal. We’ve moved from resentment to ressentiment. Whenever we feel like a David fighting a Goliath — when we feel like a bug being tortured by a giant — then we have entered the realm of ressentiment. If you feel like the Patriarchy dominates how you live your life or if you feel like liberals and their Social Justice Movement are polluting schools and destroying the culture then you’re in the throes of ressentiment.

And on that note, having carved out the emotional territory of Ressentiment, let’s look at what Nietzsche has to say about it.

Nietzschean Ressentiment

By the Waters of Babylon by Evelyn de Morgan (image via Wikimedia: Public Domain)

In his 1887 work On the Genealogy of Morals Nietzsche gives us the first systematic account of ressentiment and its role in world history. This bitter child of resentment is key to his analysis of what he calls Slave Morality especially in its Judeo-Christian form but also in the form of egalitarian-socialistic ideologies.

Ressentiment is the very foundation of Slave Morality. In the first essay of the Genealogy Nietzsche writes:

”in order to exist, slave morality always first needs a hostile external world; it needs, physiologically speaking, external stimuli in order to act at all — its action is fundamentally reaction.”

Thus Slave Morality requires the trigger of the ressentiment-inducing injustice in order to come into being. And with that foundation of ressentiment in place the pressure of this pain can turn the darkness into diamonds. Nietzsche writes that:

”The slave revolt in morality begins when ressentiment itself becomes creative and gives birth to values.”

There are plenty of historical examples we can use to give substance to Nietzsche’s account. We could look at the birth of Judaism out of the destruction of Jerusalem and her temple by the Babylonians and the forced exile in Babylon of the majority of the upper class of the Jewish kingdom of Judah. This event which shattered the power of these people led to a deep deep ressentiment which we can see in the famous Psalm 137 written by the prophet Ezekiel in exile in Babylon. He writes:

”O Daughter of Babylon, doomed to destruction, blessed is he who repays you as you have done to us. Blessed is he who seizes your infants and dashes them against the rocks.“

But there wasn’t simply ressentiment. This was the end of the worship of idolatry among the Jewish people and when the religious identity crystallised. As one Biblical scholar has put it:

“The exile is the watershed. With the exile, the religion of Israel comes to an end and Judaism begins.”

With the yoke of Babylon upon the Jewish people the ressentiment that this caused gave birth to a revaluation of values — to the Slave Morality of Judaism as Nietzsche would have it.

We could also look at the birth of the Socialist and Communist movements in the late 18th and 19th centuries out of the horrendous exploitation of the newly emerged working class in the factories of the Industrial Revolution. The great ressentiment of this time led to a new birth of Slave Morality which threatened to transform the society.

This movement too had its prophets like Marx and Engels, Proudhon and Bakunin. But with the rise of the Trade Union movement the mass energy of this ressentiment faded in the West as the workers were given fairer compensation and better working conditions.

In both of these cases we have a group of people who are subjected to an enduring injustice. Out of this pressure cooker of ressentiment new narratives were born which gave meaning to the lives of these groups.

This is what Nietzsche really sees as going on in Slave Moralities. Given the blockage of their ability to revenge themselves in this world — either by the defeat of Babylon or dominance of the capitalist employers — the ressentimentful take their revenge in an imaginary world.

The Jewish people tell a story about their God and the meaning of what has happened as a punishment. This narrative keeps them as the chosen people of their God and gives a metaphysical meaning to everything that has transpired. Lacking the stomach for the material explanation of things they look to an imaginary world of Yahweh and his whims.

And in the case of the socialists and communists the other world is not a metaphysical one but it’s just as far off. These thinkers write about utopias that are to come. Marx, drawing on a Hegelian vision of a linear evolution throughout history, prophesies the inevitable rise of the proletarian people to bring about equality and an end to injustice in the world. This fervent faith in the historical inevitability of the revolution sustained Marx through a life of abject poverty and it has sustained many more since.

In both cases we see Nietzsche’s account of the ressentimentful creating another world in order to make this present one liveable. Ultimately these new narratives of the prophets of ressentiment are essentially Marx’s opium for the masses. He writes:

”This, I surmise, constitutes the actual physiological cause of ressentiment, vengefulness and the like: a desire to deaden pains by means of the affects.”

That is to say, that this Slave Morality kills the pain of our humiliation by creating a new narrative which empowers us. This ressentimentful narrative deadens our pain by making us feel special in our own story — by making us feel as if we are the truly higher status ones.

By leveraging this “other world” the slave gets their revenge. Where reality has denied them the true revenge of the deed, they compensate themselves with an imaginary revenge of Heaven and Hell or of Karma or Utopia depending on their belief system.

The lasting impression of Nietzsche’s account of ressentiment (and later Scheler’s too) is to see ressentiment as resulting in a sort of worldly resignation. The Slaves don’t take up arms against the masters. The Jewish people did nothing against the Babylonians; instead they had to wait for liberation at the hands of the Persian army who defeated the Babylonians. All the ressentimentful could do was create their Slave Morality which inverted the values of worldliness into their metaphysical valuations in which the lamb is better than the eagle.

But as the history of modernity can well attest this is far from the case. Ressentiment doesn’t merely give birth to delusions of grandeur that serve merely to accommodate us to our unfortunate reality. In the century since Nietzsche and Scheler the power of ressentiment to impact this world has become conscious in scholars of ressentiment.

Revolutionary Ressentiment

Ressentiment and radical politics seem to be the same phenomenon viewed from the inside and the outside respectively. Every radical political group from our 21st century leftists and populists to the 20th century’s communists and fascists are driven by ressentiment. It is not a question of left or right but of radical or moderate.

The defining theme of radical politics both of the far left and the far right is a mistrust of the Establishment. On the right we can think of Trump’s language of “draining the swamp”. On the left we can think of the critiques of capitalism or in recent decades the growing emphasis on systemic racism and the patriarchy.

All this radicalism is the political fingerprint of ressentiment. As Frederic Jameson put it: “ressentiment is the very content of revolution”. And revolution is what radicals are calling for. This history of radicalism and revolution is a history of ressentiment.

When the American colonists felt the injustice of their treatment at the hands of the British they were experiencing ressentiment. When the middle and lower classes of French society were told to eat cake by the monarchy as they struggled for bread they were experiencing ressentiment. In the months after the 2020 election when Trump protesters were furious and trying to “Stop the Steal” they were filled with ressentiment. And when Black Lives Matter protestors took to the streets to protest the death of George Floyd they too were overflowing with ressentiment. The same goes for the Civil Rights Movement, the Proud Boys, the Black Panthers, the Arab Spring and Extinction Rebellion.

The furnace of hatred burns very hot and Nietzsche was mistaken in his belief that ressentiment only leads to a revaluation of this world. Indeed he himself noted that:

”the last political noblesse in Europe, that of the French seventeenth and eighteenth century, collapsed beneath the popular instincts of ressentiment”

Or as Scheler put it the French Revolution was “an enormous explosion of ressentiment”.

Jameson is not alone in amplifying this theme. Historian Hippolyte Taine looked to explain revolutions in terms of ressentiment in his work and Folger claims that revolutionary ideologies can create ressentiment.

Ressentiment in the 21st Century

The relevance of all this to our current historical moment with the so-called Culture Wars is undeniable. It seems that we need to hate and be angry in order to bring about mass change. Only by being set on fire in this way can we find the motivation to fight for change.

Our gaping wounds of ressentiment are only fuelled by the mob-like nature of the libertarian wild west that is the internet and social media. This 21st century experience provides fertile ground for the two traits that make ressentiment out of resentment.

Firstly the experience of our complete inconsequence amid the billions of posts on social media can leave us with the sense of impotence that is essential for ressentiment. And secondly the outrage porn of the social media algorithms makes the condition chronic as it feeds us post after post which reinforces the ressentimentful narrative.

We need only look at the wave of ressentiment in the red ocean outside of America’s great urban centres that we’ve looked at in recent instalments of The Living Philosophy. This radical right wave of Populism — fuelled by the prophets of Fox News — feel a bitterness against the Rich Men North of Richmond and the well-educated SJWs who are trying to take over their country through the education system.

On the other side of the trenches the Social Justice Movement has whipped up cyclones of ressentiment over the systemic racism and sexism, transphobia and of course capitalism. From BLM to #MeToo we’ve seen ressentiment reaching a boiling point on the left.

Looking at these pressure cookers of radicalism, there can be no doubt about the power of ressentiment to bring about mass change. The seeming unassailability of the monolithic abstractions like “the Establishment”, ”the System” and “the State” have proven to be anything but unassailable. These towering Leviathans may seem impossible to nudge even an inch but with the ressentiment at scale that is the internet these Leviathans are under constant siege. The ressentiment of the mob is the defining force of the 21st century.

There are many more fruitful avenues we could explore on this theme of ressentiment. It is hard to resist mapping over ressentiment with our recent explorations of Liminality but we will leave that for a possible future article.

Another theme which we’ve unfortunately excluded from this instalment is the connections between ressentiment and the modern darlings of equality and democracy. This is a theme we will certainly be returning to in a future article as we explore the ressentimentful instability that is inherent in Democracy and which goes to explain why the modern era more than any other has been characterised by ressentiment.