Once upon a time there were only two religious archetypes. One could be found in rural areas and was associated with miraculous deeds and supernatural abilities; this was the archetype of the magician. The other could be found in the urban areas with higher densities of population with their kingly courts and their centres of learning and bureaucracy; this was the archetype of the priest.

But with the unfolding of history a new religious archetype emerged. While this new archetypal figure might perform the occasional trick or miracle they were not magicians. And while they were well-versed in the priestly tradition they were not priests.

This new type emerged from the margins. They were outcasts living at the edge of the inside. They were neither insiders nor total outsiders. They were liminal entities filled with a wild impressive energy. This new archetype came to be known as the prophet.

But before we talk about the prophet let’s talk a little more about the relationship between the priests and the magicians.

Priests and Magicians

Beyond the city walls of ancient cities the world wasn’t the human playground that it is today. Wilderness wasn’t a walled off reserve where tourists went to feed the dingoes. The world was filled with a little more danger. Civilisation was the exception rather than the rule.

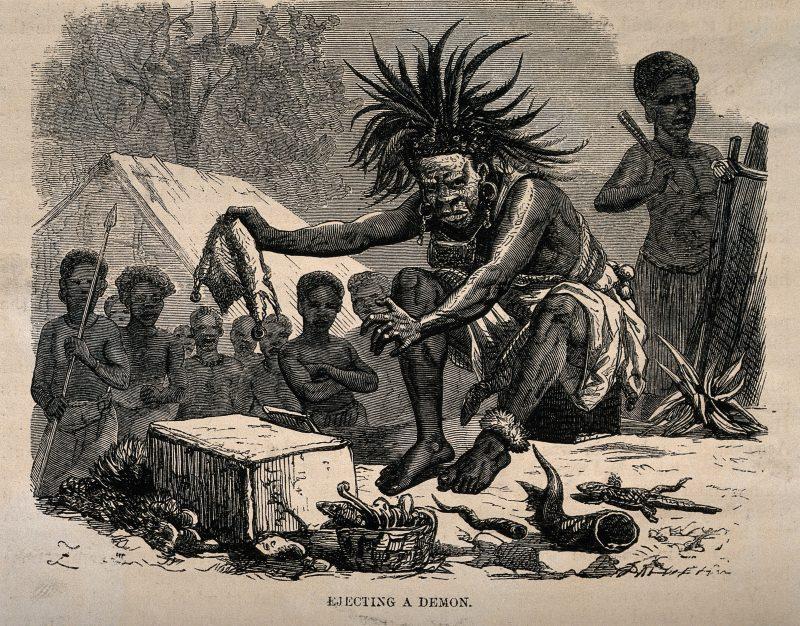

Out amongst this wilder world there were the tribes and villages which existed in a different reality to the kings and priests with their palaces and temples. And the archetypal figure of this rural world was the magician.

These magicians were what Max Weber called Charismatic figures. They could perform miraculous events like bringing rain with a rain dance or healing using their shamanic powers. They seemed to tap into forces that were supernatural.

It was around such figures and such a magical worldview that the rural form of religion orbited.

Meanwhile in the cities things were very different. At the heart of every major pre-modern civilisation there was a religion. The religion of priests had a power which rivalled that of the kings and sometimes this led to political power struggles as in the case of Tutankhamun’s parents Akhenaten and Nefertiti and the Ancient Egyptian priesthood.

The religion of the priests was a matter of routinisation — the institutionalising of such charismatic figures and turning them into saints, gods and demigods in the institutional religions of the city.

The main practice of the priestly religion was sacrifice. The magical Moses becomes the holy man of the priestly Hebrew tradition and sacrifices are offered to the god of Moses according to strict rules and procedures tightly controlled by the priestly class.

There was a certain harmony in the co-existence of these two breeds of religion. The institutionalised religion experienced no threat from the magicians of the rural world; instead they integrated these figures into their religion and institutionalised them and ordered them — using them to bolster their own religion.

Prophets

It is into the midst of this dichotomy that the Prophet enters the scene. The Prophet is neither the ecstatic holy man of the magician nor is he the measured powerful priest.

The Prophet is a marginal — an outsider. But he’s not an alien. He’s not entirely separate. He is as the theologian Richard Rohr has put it at the “edge of the inside”. The Prophet is close enough to be well-versed in the tradition. They know the priestly tradition; they understand the system. They understand where it is broken; and more importantly they are free to criticise the tradition.

Power and the Priest

The priest cannot truly criticise their tradition. For one they are caught within the power structure of the institution. This does two things. This power structure has as Foucault would point out two different effects. On the one hand there is the traditional understanding of power as punishing. The priest is kept in line by the institution; stepping out of line is grounds for punishment or excommunication.

But there is a second more important and more insidious way that the priest is kept in line. This is through what Foucault calls the constituting nature of power. That is to say that power doesn’t just keep us in line and cow our opinions. The power structure also shapes us — shapes the way we think. We are created and moulded by this power structure. The incentive structure of the institution makes it easier to go along with the institutionalised way of doing things and accepting this imperfect path as the lesser of evils and as the closest approximation to the ideal. We are lured into conformity by the safety and comfort of the institution.

With the carrot and stick of the institutional power structure, the priest is not the source of renewal. Weber contradicts Nietzsche’s analysis from the Genealogy of Morals which sees priests as bringing about a revaluation of all values and replacing Master Morality with Slave Morality. Weber’s account instead points us towards the prophet. It is with the prophets that the message of salvation comes and it is the urgency of this message that drives the prophet even though the world might reject them and the powers that be try to do away with them. The work of the prophet isn’t an idle intellectual game; it’s an existential question — a matter of life and death.

Refusal of the Call

The prophet is outside the institutional power structure. They are outsiders — not by choice. This is a key characteristic of the prophet. They are not creatures of conscious will. The prophet is passive; rather than being a rebel or revolutionary, the prophet is merely the greatest servant or the emptiest vessel of the higher power.

As such the prophet does not choose to become an outsider nor are they born as outsiders. Prophets were once on the inside; they were once regular folk. But then they were torn from their world — not by choice but by a higher power.

Fans of Joseph Campbell will recognise the initial arc of the Hero’s Journey here with the hero’s unwillingness to go on the journey and their refusal of the call. It’s something we see play out directly in many of the Biblical prophets. The prophet Jonah tried to escape his call and ended up inside the belly of the whale-like leviathan.

The prophet is dragged on their journey by something beyond their will. This is not the charismatic cult leader confidently leading his chosen people away. This is an individual who is torn from their comfortable life and pushed into the role of prophet. A higher power calls them or gives them an illumination. They experience a shattering encounter with the truth and they cannot go back to their previous life.

There is no better example of this than the founder of Islam. Muhammad went from being a successful trader in Mecca until he had the role of prophet thrust on him by the force of revelation. He had to speak against his own tribe and their excesses and go to war with them.

But this outsider position of the prophet gives them a vantage point from which to look at their old world — a world which has become alien and intolerable to them. Being outside they are no longer controlled by the incentives of the inside. They are free to think differently and to honestly evaluate the system.

Personal Aspect and Revelation

Aside from this divine call, there are two other key elements of the prophet archetype: charisma and revelation. That is, there’s their personal exemplary lives and there is the doctrine that they reveal.

In the case of Muhammad we have the life of the prophet which is a lofty ideal that Muslims are encouraged to emulate and then there is the doctrine that was revealed through him i.e. the Quran. In the case of Jesus there is his life and then there is the truth that was revealed through him. In the case of the Buddha there is his lived example and there is the teachings — the dharma — that he revealed.

In each of these cases we can see the two elements of the prophet dancing with each other. And the degree to which each of these elements varies gives us two different types of prophetic traditions. On the one hand we have the Exemplary Prophets and on the other we have the Ethical Prophets.

Exemplary and Ethical Prophecy

In the case of exemplary prophets the primary emphasis is on how life is to be lived while the doctrine is secondary. In the case of ethical prophecy it’s the opposite — the transcendentally revealed doctrine is primary and the emphasis on behaviour is less prominent.

It’s worth noting that in both cases the two elements are important. The revelation is still important in the case of the exemplary prophet and the life of the prophet is still important in the case of an ethical prophet. Hence in the life of Muhammad his life isn’t the most important part by far but nevertheless he is an ideal for how a Muslim should conduct themselves. It’s not necessary to live like Muhammad but it is admirable.

Christianity also fits in this ethical mould. While the life of Jesus is admirable and we would do well to emulate it, the truly important element of Christianity is the revelation — is the salvation that comes from believing in Christ and the resurrection. It is the ethical component that dominates over the exemplary.

However in the case of an exemplary prophet like Buddha his teachings i.e. the dharma is obviously very important but not as important as life. In one of the famous stories of the Buddha he compares the dharma to a raft which helps us cross the river. Why he asks us would you keep carrying the raft when you have reached the other side. And so the revealed doctrine is a means to a better way of being and not the end in itself.

We can also place Stoicism, Epicureanism and Cynics like Diogenes in this category. These schools of philosophy were almost religions in the ancient world. These were schools that encouraged us to live good lives. The doctrines weren’t what mattered but the lives we led. As with Buddhism, these doctrines could enable this better life but they were not the point. For example the Epicurean poem On the Nature of Things by Lucretius teaches the doctrines of atomism and of the non-existence of an afterlife. These doctrines were important for liberating us from the fears and beliefs that keep us from living the good life.

Elitist Exemplarys

If success is measured in numbers then the ethical prophecies are infinitely more successful than the exemplary prophecies. Weber gives good reasons for this.

Exemplary prophecies like Buddhism or Stoicism put a lot of pressure on followers with their excessively high demands for conduct. There is a certain elitism to this type of school since there are not many people that are free to, or capable of, following these strict ways of life. These high demands on conduct limited the development of a mass following for the Exemplary Prophecies.

In Asia, Buddhism spread like wildfire in the cities and courts of its time but was effectively unimportant in rural areas where the magical worldview still reigned supreme. The priestly class ended up using this popular belief in magic to drive back Buddhism in both India and China effecting what Weber called a:

“transformation of the world into a magical garden”

Conclusion

By the time the age of the prophets had come to an end the landscape of religion was transformed. The magical religions existed only in the pockets where Eurasian civilisation had yet to penetrate. Meanwhile the sacrificial religions of the pre-prophetic religions were all but wiped out in the West though they fared better in the East with their ability to beat back the exemplary prophetic tradition of Buddhism.

The Prophet was a new archetype that brought in a new way of being religious. It was a revolution against the priestly religion from the inside. This rupture in the tradition brought about something new.

There have been many that have drawn comparisons between the era of the prophets and our own modern times. It is a time of liminality in which we can see the re-emergence of the exemplary prophetic traditions like Buddhism and Stoicism.

I can’t help but wonder whether this is a new age for the emergence of the Prophet archetype or perhaps whether an even newer archetype might see its day to emerge and take us into the next period of stability in our meaning system. In such a case we should probably expect it to be as different from the prophet as the prophet was from the priest or the magician. An outsider still perhaps but in what way?

Once upon a time there were only two religious archetypes. One could be found in rural areas and was associated with miraculous deeds and supernatural abilities; this was the archetype of the magician. The other could be found in the urban areas with higher densities of population with their kingly courts and their centres of learning and bureaucracy; this was the archetype of the priest.

But with the unfolding of history a new religious archetype emerged. While this new archetypal figure might perform the occasional trick or miracle they were not magicians. And while they were well-versed in the priestly tradition they were not priests.

This new type emerged from the margins. They were outcasts living at the edge of the inside. They were neither insiders nor total outsiders. They were liminal entities filled with a wild impressive energy. This new archetype came to be known as the prophet.

But before we talk about the prophet let’s talk a little more about the relationship between the priests and the magicians.

Priests and Magicians

Beyond the city walls of ancient cities the world wasn’t the human playground that it is today. Wilderness wasn’t a walled off reserve where tourists went to feed the dingoes. The world was filled with a little more danger. Civilisation was the exception rather than the rule.

Out amongst this wilder world there were the tribes and villages which existed in a different reality to the kings and priests with their palaces and temples. And the archetypal figure of this rural world was the magician.

These magicians were what Max Weber called Charismatic figures. They could perform miraculous events like bringing rain with a rain dance or healing using their shamanic powers. They seemed to tap into forces that were supernatural.

It was around such figures and such a magical worldview that the rural form of religion orbited.

Meanwhile in the cities things were very different. At the heart of every major pre-modern civilisation there was a religion. The religion of priests had a power which rivalled that of the kings and sometimes this led to political power struggles as in the case of Tutankhamun’s parents Akhenaten and Nefertiti and the Ancient Egyptian priesthood.

The religion of the priests was a matter of routinisation — the institutionalising of such charismatic figures and turning them into saints, gods and demigods in the institutional religions of the city.

The main practice of the priestly religion was sacrifice. The magical Moses becomes the holy man of the priestly Hebrew tradition and sacrifices are offered to the god of Moses according to strict rules and procedures tightly controlled by the priestly class.

There was a certain harmony in the co-existence of these two breeds of religion. The institutionalised religion experienced no threat from the magicians of the rural world; instead they integrated these figures into their religion and institutionalised them and ordered them — using them to bolster their own religion.

Prophets

It is into the midst of this dichotomy that the Prophet enters the scene. The Prophet is neither the ecstatic holy man of the magician nor is he the measured powerful priest.

The Prophet is a marginal — an outsider. But he’s not an alien. He’s not entirely separate. He is as the theologian Richard Rohr has put it at the “edge of the inside”. The Prophet is close enough to be well-versed in the tradition. They know the priestly tradition; they understand the system. They understand where it is broken; and more importantly they are free to criticise the tradition.

Power and the Priest

The priest cannot truly criticise their tradition. For one they are caught within the power structure of the institution. This does two things. This power structure has as Foucault would point out two different effects. On the one hand there is the traditional understanding of power as punishing. The priest is kept in line by the institution; stepping out of line is grounds for punishment or excommunication.

But there is a second more important and more insidious way that the priest is kept in line. This is through what Foucault calls the constituting nature of power. That is to say that power doesn’t just keep us in line and cow our opinions. The power structure also shapes us — shapes the way we think. We are created and moulded by this power structure. The incentive structure of the institution makes it easier to go along with the institutionalised way of doing things and accepting this imperfect path as the lesser of evils and as the closest approximation to the ideal. We are lured into conformity by the safety and comfort of the institution.

With the carrot and stick of the institutional power structure, the priest is not the source of renewal. Weber contradicts Nietzsche’s analysis from the Genealogy of Morals which sees priests as bringing about a revaluation of all values and replacing Master Morality with Slave Morality. Weber’s account instead points us towards the prophet. It is with the prophets that the message of salvation comes and it is the urgency of this message that drives the prophet even though the world might reject them and the powers that be try to do away with them. The work of the prophet isn’t an idle intellectual game; it’s an existential question — a matter of life and death.

Refusal of the Call

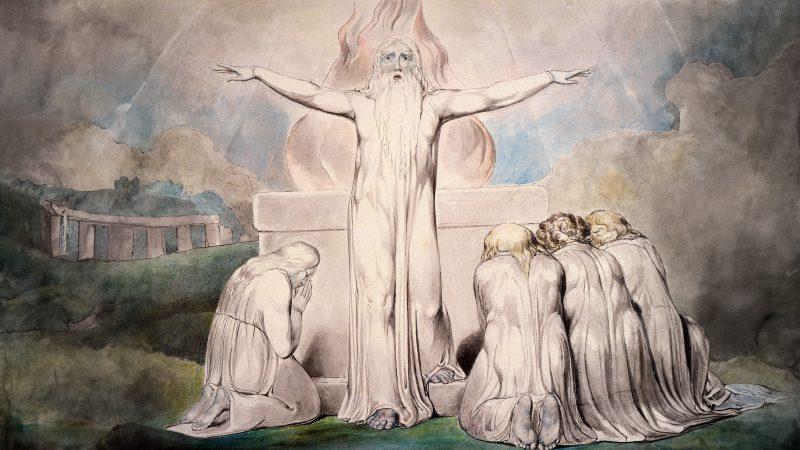

The prophet is outside the institutional power structure. They are outsiders — not by choice. This is a key characteristic of the prophet. They are not creatures of conscious will. The prophet is passive; rather than being a rebel or revolutionary, the prophet is merely the greatest servant or the emptiest vessel of the higher power.

As such the prophet does not choose to become an outsider nor are they born as outsiders. Prophets were once on the inside; they were once regular folk. But then they were torn from their world — not by choice but by a higher power.

Fans of Joseph Campbell will recognise the initial arc of the Hero’s Journey here with the hero’s unwillingness to go on the journey and their refusal of the call. It’s something we see play out directly in many of the Biblical prophets. The prophet Jonah tried to escape his call and ended up inside the belly of the whale-like leviathan.

The prophet is dragged on their journey by something beyond their will. This is not the charismatic cult leader confidently leading his chosen people away. This is an individual who is torn from their comfortable life and pushed into the role of prophet. A higher power calls them or gives them an illumination. They experience a shattering encounter with the truth and they cannot go back to their previous life.

There is no better example of this than the founder of Islam. Muhammad went from being a successful trader in Mecca until he had the role of prophet thrust on him by the force of revelation. He had to speak against his own tribe and their excesses and go to war with them.

But this outsider position of the prophet gives them a vantage point from which to look at their old world — a world which has become alien and intolerable to them. Being outside they are no longer controlled by the incentives of the inside. They are free to think differently and to honestly evaluate the system.

Personal Aspect and Revelation

Aside from this divine call, there are two other key elements of the prophet archetype: charisma and revelation. That is, there’s their personal exemplary lives and there is the doctrine that they reveal.

In the case of Muhammad we have the life of the prophet which is a lofty ideal that Muslims are encouraged to emulate and then there is the doctrine that was revealed through him i.e. the Quran. In the case of Jesus there is his life and then there is the truth that was revealed through him. In the case of the Buddha there is his lived example and there is the teachings — the dharma — that he revealed.

In each of these cases we can see the two elements of the prophet dancing with each other. And the degree to which each of these elements varies gives us two different types of prophetic traditions. On the one hand we have the Exemplary Prophets and on the other we have the Ethical Prophets.

Exemplary and Ethical Prophecy

In the case of exemplary prophets the primary emphasis is on how life is to be lived while the doctrine is secondary. In the case of ethical prophecy it’s the opposite — the transcendentally revealed doctrine is primary and the emphasis on behaviour is less prominent.

It’s worth noting that in both cases the two elements are important. The revelation is still important in the case of the exemplary prophet and the life of the prophet is still important in the case of an ethical prophet. Hence in the life of Muhammad his life isn’t the most important part by far but nevertheless he is an ideal for how a Muslim should conduct themselves. It’s not necessary to live like Muhammad but it is admirable.

Christianity also fits in this ethical mould. While the life of Jesus is admirable and we would do well to emulate it, the truly important element of Christianity is the revelation — is the salvation that comes from believing in Christ and the resurrection. It is the ethical component that dominates over the exemplary.

However in the case of an exemplary prophet like Buddha his teachings i.e. the dharma is obviously very important but not as important as life. In one of the famous stories of the Buddha he compares the dharma to a raft which helps us cross the river. Why he asks us would you keep carrying the raft when you have reached the other side. And so the revealed doctrine is a means to a better way of being and not the end in itself.

We can also place Stoicism, Epicureanism and Cynics like Diogenes in this category. These schools of philosophy were almost religions in the ancient world. These were schools that encouraged us to live good lives. The doctrines weren’t what mattered but the lives we led. As with Buddhism, these doctrines could enable this better life but they were not the point. For example the Epicurean poem On the Nature of Things by Lucretius teaches the doctrines of atomism and of the non-existence of an afterlife. These doctrines were important for liberating us from the fears and beliefs that keep us from living the good life.

Elitist Exemplarys

If success is measured in numbers then the ethical prophecies are infinitely more successful than the exemplary prophecies. Weber gives good reasons for this.

Exemplary prophecies like Buddhism or Stoicism put a lot of pressure on followers with their excessively high demands for conduct. There is a certain elitism to this type of school since there are not many people that are free to, or capable of, following these strict ways of life. These high demands on conduct limited the development of a mass following for the Exemplary Prophecies.

In Asia, Buddhism spread like wildfire in the cities and courts of its time but was effectively unimportant in rural areas where the magical worldview still reigned supreme. The priestly class ended up using this popular belief in magic to drive back Buddhism in both India and China effecting what Weber called a:

“transformation of the world into a magical garden”

Conclusion

By the time the age of the prophets had come to an end the landscape of religion was transformed. The magical religions existed only in the pockets where Eurasian civilisation had yet to penetrate. Meanwhile the sacrificial religions of the pre-prophetic religions were all but wiped out in the West though they fared better in the East with their ability to beat back the exemplary prophetic tradition of Buddhism.

The Prophet was a new archetype that brought in a new way of being religious. It was a revolution against the priestly religion from the inside. This rupture in the tradition brought about something new.

There have been many that have drawn comparisons between the era of the prophets and our own modern times. It is a time of liminality in which we can see the re-emergence of the exemplary prophetic traditions like Buddhism and Stoicism.

I can’t help but wonder whether this is a new age for the emergence of the Prophet archetype or perhaps whether an even newer archetype might see its day to emerge and take us into the next period of stability in our meaning system. In such a case we should probably expect it to be as different from the prophet as the prophet was from the priest or the magician. An outsider still perhaps but in what way?

Once upon a time there were only two religious archetypes. One could be found in rural areas and was associated with miraculous deeds and supernatural abilities; this was the archetype of the magician. The other could be found in the urban areas with higher densities of population with their kingly courts and their centres of learning and bureaucracy; this was the archetype of the priest.

But with the unfolding of history a new religious archetype emerged. While this new archetypal figure might perform the occasional trick or miracle they were not magicians. And while they were well-versed in the priestly tradition they were not priests.

This new type emerged from the margins. They were outcasts living at the edge of the inside. They were neither insiders nor total outsiders. They were liminal entities filled with a wild impressive energy. This new archetype came to be known as the prophet.

But before we talk about the prophet let’s talk a little more about the relationship between the priests and the magicians.

Priests and Magicians

Beyond the city walls of ancient cities the world wasn’t the human playground that it is today. Wilderness wasn’t a walled off reserve where tourists went to feed the dingoes. The world was filled with a little more danger. Civilisation was the exception rather than the rule.

Out amongst this wilder world there were the tribes and villages which existed in a different reality to the kings and priests with their palaces and temples. And the archetypal figure of this rural world was the magician.

These magicians were what Max Weber called Charismatic figures. They could perform miraculous events like bringing rain with a rain dance or healing using their shamanic powers. They seemed to tap into forces that were supernatural.

It was around such figures and such a magical worldview that the rural form of religion orbited.

Meanwhile in the cities things were very different. At the heart of every major pre-modern civilisation there was a religion. The religion of priests had a power which rivalled that of the kings and sometimes this led to political power struggles as in the case of Tutankhamun’s parents Akhenaten and Nefertiti and the Ancient Egyptian priesthood.

The religion of the priests was a matter of routinisation — the institutionalising of such charismatic figures and turning them into saints, gods and demigods in the institutional religions of the city.

The main practice of the priestly religion was sacrifice. The magical Moses becomes the holy man of the priestly Hebrew tradition and sacrifices are offered to the god of Moses according to strict rules and procedures tightly controlled by the priestly class.

There was a certain harmony in the co-existence of these two breeds of religion. The institutionalised religion experienced no threat from the magicians of the rural world; instead they integrated these figures into their religion and institutionalised them and ordered them — using them to bolster their own religion.

Prophets

It is into the midst of this dichotomy that the Prophet enters the scene. The Prophet is neither the ecstatic holy man of the magician nor is he the measured powerful priest.

The Prophet is a marginal — an outsider. But he’s not an alien. He’s not entirely separate. He is as the theologian Richard Rohr has put it at the “edge of the inside”. The Prophet is close enough to be well-versed in the tradition. They know the priestly tradition; they understand the system. They understand where it is broken; and more importantly they are free to criticise the tradition.

Power and the Priest

The priest cannot truly criticise their tradition. For one they are caught within the power structure of the institution. This does two things. This power structure has as Foucault would point out two different effects. On the one hand there is the traditional understanding of power as punishing. The priest is kept in line by the institution; stepping out of line is grounds for punishment or excommunication.

But there is a second more important and more insidious way that the priest is kept in line. This is through what Foucault calls the constituting nature of power. That is to say that power doesn’t just keep us in line and cow our opinions. The power structure also shapes us — shapes the way we think. We are created and moulded by this power structure. The incentive structure of the institution makes it easier to go along with the institutionalised way of doing things and accepting this imperfect path as the lesser of evils and as the closest approximation to the ideal. We are lured into conformity by the safety and comfort of the institution.

With the carrot and stick of the institutional power structure, the priest is not the source of renewal. Weber contradicts Nietzsche’s analysis from the Genealogy of Morals which sees priests as bringing about a revaluation of all values and replacing Master Morality with Slave Morality. Weber’s account instead points us towards the prophet. It is with the prophets that the message of salvation comes and it is the urgency of this message that drives the prophet even though the world might reject them and the powers that be try to do away with them. The work of the prophet isn’t an idle intellectual game; it’s an existential question — a matter of life and death.

Refusal of the Call

The prophet is outside the institutional power structure. They are outsiders — not by choice. This is a key characteristic of the prophet. They are not creatures of conscious will. The prophet is passive; rather than being a rebel or revolutionary, the prophet is merely the greatest servant or the emptiest vessel of the higher power.

As such the prophet does not choose to become an outsider nor are they born as outsiders. Prophets were once on the inside; they were once regular folk. But then they were torn from their world — not by choice but by a higher power.

Fans of Joseph Campbell will recognise the initial arc of the Hero’s Journey here with the hero’s unwillingness to go on the journey and their refusal of the call. It’s something we see play out directly in many of the Biblical prophets. The prophet Jonah tried to escape his call and ended up inside the belly of the whale-like leviathan.

The prophet is dragged on their journey by something beyond their will. This is not the charismatic cult leader confidently leading his chosen people away. This is an individual who is torn from their comfortable life and pushed into the role of prophet. A higher power calls them or gives them an illumination. They experience a shattering encounter with the truth and they cannot go back to their previous life.

There is no better example of this than the founder of Islam. Muhammad went from being a successful trader in Mecca until he had the role of prophet thrust on him by the force of revelation. He had to speak against his own tribe and their excesses and go to war with them.

But this outsider position of the prophet gives them a vantage point from which to look at their old world — a world which has become alien and intolerable to them. Being outside they are no longer controlled by the incentives of the inside. They are free to think differently and to honestly evaluate the system.

Personal Aspect and Revelation

Aside from this divine call, there are two other key elements of the prophet archetype: charisma and revelation. That is, there’s their personal exemplary lives and there is the doctrine that they reveal.

In the case of Muhammad we have the life of the prophet which is a lofty ideal that Muslims are encouraged to emulate and then there is the doctrine that was revealed through him i.e. the Quran. In the case of Jesus there is his life and then there is the truth that was revealed through him. In the case of the Buddha there is his lived example and there is the teachings — the dharma — that he revealed.

In each of these cases we can see the two elements of the prophet dancing with each other. And the degree to which each of these elements varies gives us two different types of prophetic traditions. On the one hand we have the Exemplary Prophets and on the other we have the Ethical Prophets.

Exemplary and Ethical Prophecy

In the case of exemplary prophets the primary emphasis is on how life is to be lived while the doctrine is secondary. In the case of ethical prophecy it’s the opposite — the transcendentally revealed doctrine is primary and the emphasis on behaviour is less prominent.

It’s worth noting that in both cases the two elements are important. The revelation is still important in the case of the exemplary prophet and the life of the prophet is still important in the case of an ethical prophet. Hence in the life of Muhammad his life isn’t the most important part by far but nevertheless he is an ideal for how a Muslim should conduct themselves. It’s not necessary to live like Muhammad but it is admirable.

Christianity also fits in this ethical mould. While the life of Jesus is admirable and we would do well to emulate it, the truly important element of Christianity is the revelation — is the salvation that comes from believing in Christ and the resurrection. It is the ethical component that dominates over the exemplary.

However in the case of an exemplary prophet like Buddha his teachings i.e. the dharma is obviously very important but not as important as life. In one of the famous stories of the Buddha he compares the dharma to a raft which helps us cross the river. Why he asks us would you keep carrying the raft when you have reached the other side. And so the revealed doctrine is a means to a better way of being and not the end in itself.

We can also place Stoicism, Epicureanism and Cynics like Diogenes in this category. These schools of philosophy were almost religions in the ancient world. These were schools that encouraged us to live good lives. The doctrines weren’t what mattered but the lives we led. As with Buddhism, these doctrines could enable this better life but they were not the point. For example the Epicurean poem On the Nature of Things by Lucretius teaches the doctrines of atomism and of the non-existence of an afterlife. These doctrines were important for liberating us from the fears and beliefs that keep us from living the good life.

Elitist Exemplarys

If success is measured in numbers then the ethical prophecies are infinitely more successful than the exemplary prophecies. Weber gives good reasons for this.

Exemplary prophecies like Buddhism or Stoicism put a lot of pressure on followers with their excessively high demands for conduct. There is a certain elitism to this type of school since there are not many people that are free to, or capable of, following these strict ways of life. These high demands on conduct limited the development of a mass following for the Exemplary Prophecies.

In Asia, Buddhism spread like wildfire in the cities and courts of its time but was effectively unimportant in rural areas where the magical worldview still reigned supreme. The priestly class ended up using this popular belief in magic to drive back Buddhism in both India and China effecting what Weber called a:

“transformation of the world into a magical garden”

Conclusion

By the time the age of the prophets had come to an end the landscape of religion was transformed. The magical religions existed only in the pockets where Eurasian civilisation had yet to penetrate. Meanwhile the sacrificial religions of the pre-prophetic religions were all but wiped out in the West though they fared better in the East with their ability to beat back the exemplary prophetic tradition of Buddhism.

The Prophet was a new archetype that brought in a new way of being religious. It was a revolution against the priestly religion from the inside. This rupture in the tradition brought about something new.

There have been many that have drawn comparisons between the era of the prophets and our own modern times. It is a time of liminality in which we can see the re-emergence of the exemplary prophetic traditions like Buddhism and Stoicism.

I can’t help but wonder whether this is a new age for the emergence of the Prophet archetype or perhaps whether an even newer archetype might see its day to emerge and take us into the next period of stability in our meaning system. In such a case we should probably expect it to be as different from the prophet as the prophet was from the priest or the magician. An outsider still perhaps but in what way?