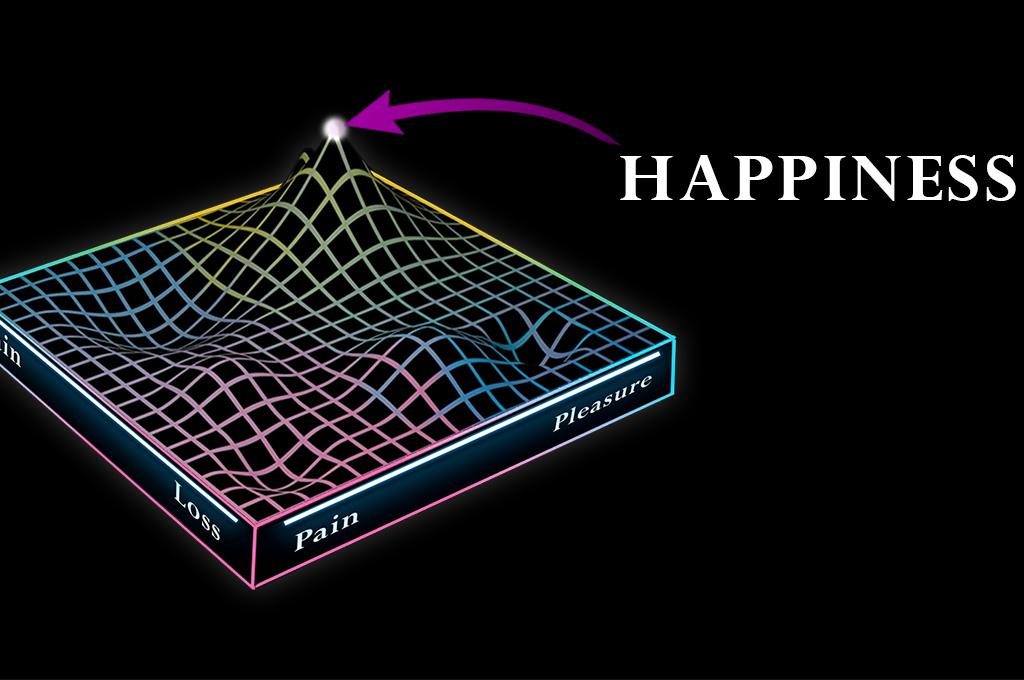

One answer is offered by the Hedonists. They tell us that the good life is simply a question of feeling good and feeling bad. We can plot this on a simple line from pain to pleasure.; the closer you are to the pleasurable end of the scale, the better your life is.

But other philosophers aren’t satisfied by this. The trouble with this pain/pleasure map of the good life is that it lacks any relationship to consequences (which can’t be measured by a moment in time). If the good life was simply about pleasure then why not take out a bank loan and have a lot of fun — take heroin, go skydiving and party like there’s no tomorrow?

The answer is simple: because there are longer-term consequences to our actions. Today’s partying is tomorrow’s hangover.

We can map these consequences by adding another line running north-south from gain to loss. We can think of gain as pleasure extended over time — of where are pleasure is trending through time.

If our actions or experiences now trend towards a lower level of future pleasure then we can call it loss; if our actions or experiences trend towards a higher level of future pleasure then we can call it gain;

With this two-dimensional map we factor in the consequences of our actions for our future as part of our life satisfaction. We integrate the element of Time which Heidegger finds so essential to the human condition. The good life then is the convergence of pleasure in the moment and the trajectory of our lives.

But this map also runs into a wall very quickly when we consider the fate of lotto winners and paraplegics. In both of these cases we see a short-term spike in opposite directions but when asked to predict how happy they will be in a couple of years the happiness of paraplegics and lottery winners is more or less the same.

And it’s not just a property of dramatic examples. There are countless stories of people achieving their long-term goals — they bought the house or they got the promotion — and instead of feeling a burst of fulfilment they find the rug ripped from under them. These events are associated with the trope of the midlife crisis but they can happen at any point in life. The simple equation of “gain-pleasure = good life” simply doesn’t fit reality.

Eudaimonia: the third dimension

The term eudaimonia is an Ancient Greek word used by ancient philosophers like Socrates, Aristotle and the Stoics. It is sometimes translated as happiness, other times as flourishing, satisfaction or fulfilment but none of these quite captures the full meaning of the term. The best way to understand what eudaimonia is, is by looking at its much more common and familiar opposite depression.

In his book Become Who You Are — from which this video’s triple axis theory of the good life is being drawn — the author Ryan Bush outlines the four core traits to the experience of depression:

- Low mood

- Low vitality

- Low self-esteem

- Strong sense of self

By inverting these lows to highs we can form a picture of what eudaimonia is:

- High mood

- High vitality

- High self-esteem

- Strong sense of self (Note that both depression and eudaimonia share the strong sense of self — we’ll return to this point a little later.)

How to Eudaimonia

The natural next question is: how do we reach eudaimonia? It’s fairly obvious that we reach pleasure by increasing our positive emotions and that we increase gain by improving our circumstances but how exactly do we move towards eudaimonia and away from depression?

With the pop culture portrayal of depression as sadness and lethargy we might think that pleasure might be the solution but while this may temporarily impact the first and second components of depression i.e. low mood and low vitality, the effect will be short-lived.

That is because low mood and low vitality are symptoms. The deeper cause is the third component: low self-esteem. We can shoot the arrows of pleasure high in the sky but the gravity of depression’s low self-esteem will drag our mood and vitality back to the level of our self-esteem. This z-axis of depression/eudaimonia is the hidden force of gravity that pulls lotto winners and paraplegics back into alignment with each other. And so if we wish to become happier then it is towards this deeper root that we must direct our attention.

On this front we have two options. We can try to change component three — our low-self-esteem — or we can go after component four — depression’s strong sense of self.

The Spiritual Path: happiness by non-attachment

In the latter case we can reduce our experience of depression by weakening our sense of self. This is the path of spirituality. The ego as the spiritual writers tell us, is the source of all human misery. Hence by destroying —or to put it more spiritually by transcending — the ego we can reach a state of deep content away from the nagging voice of the monkey-mind ego.

But there is a white lie in the spiritual account.

In Become Who You Are, Bush presents a suitable analogy for this:

Imagine you are at home one cold winter night and you have a HVAC unit which is capable of being both a radiator and an air conditioner. Anyway this one cold night the unit malfunctions and instead of giving out lovely warm air it starts blowing out freezing cold air.

You don’t know anything about how to repair one of these things and meanwhile your room is growing increasingly unliveable by the minute.

You can take a chance on trying to figure out how to repair the thing; if you are successful you will have a very nice situation. Or you could take a golf club to the unit and in so doing destroy any chance of getting some warm air coming out but by the same token the room doesn’t get any colder. Do you try and fix the machine? Or do you destroy it and accept reality as it is?

The spiritual path in this (admittedly rather loaded) analogy is the way of the golf club. You destroy the unit and abandon your strong sense of self in order to form a relationship with reality as it is.

So much for the attack on component four. If we are not looking to go after our strong sense of self then it seems the best path forward is via component three: improving our self-esteem.

The Neuroscience of Self-Esteem

Before we look at how we do this let’s first examine Bush’s account of the neuroscience of self-esteem.

The Default Mode Network is a network of centres across the brain including the medial Pre-Frontal Cortex, the posterior cingulate cortex, the precuneus, and the angular gyrus.

The Default Mode Network is best known for being active when we are not focussed on the outside world for example when we are daydreaming or when our minds are wandering — hence the “default” in Default Mode Network.

When we are engaged in a task the Default Mode Network is usually downregulated; but rather tellingly if the task that we are engaged in is a self-oriented task like reflecting on something from our past or thinking about our future then the network lights up.

Some areas of the Default Mode Network control the release of serotonin which is connected in with our sense of relative status and value of ourselves and others. Another key subsystem is responsible for our ability to take the perspective of others and get inside what they are thinking and feeling.

What emerges is a brain network that is fundamental to our self-esteem — something which a 2016 paper by a Chinese team in Chongqing made explicit when they concluded that “[Trait Self-Esteem] is linked to core regions in the default mode network”.

Another group of researchers, Davey et al in 2016 went a step further and suggested that the Default Mode Network is the neurological basis for the conscious awareness of the self. All of this fits nicely with those studies which have found meditation decreases activity in the Default Mode Network and that psychedelics interrupt activity in this network as well.

We can see then that our destruction of the HVAC unit in the analogy earlier is neuroscientifically speaking the de-emphasis on the central importance of the Default Mode Network. Meditation takes us out of this monkey mind and psychedelics can bring about an ego death through the disruption of this network.

All of this fits well with the idea that the Default Mode Network is the centre of our self-esteem in the brain and that the path of spirituality works by weakening this sense of self rather than improving it i.e. taking a bat to the HVAC machine.

So how do we fix the HVAC machine? How do we raise our self-esteem so that we are warmed by the tropical air of eudaimonia rather than frozen by the cold air of depression?

The answer will sound strange to the 21st-century ear but would sound commonplace to an Ancient Greek or Roman ear. The answer is virtue.

Virtue: the royal road to Eudaimonia

The beating heart of Stoicism — one that is more or less absent from the 21st-century Neo-Stoic revival — is the Stoic axiom that “virtue is sufficient for happiness/eudaimonia”. When Socrates chose death over an escape into exile via bribery, he was choosing virtue. When Cato the Younger chose Civil War in Ancient Rome over compromise with Caesar’s tyranny he was choosing virtue. When Diogenes was hugging icy statues or whacking off in the marketplace he was choosing a life of virtue.

Virtue sounds prudish and self-righteous to the 21st-century ear. It is more commonly heard in the phrase “virtue signalling” as a way of criticising performative moralising than it is in the context of the good life. But it was not this way for the Greeks and Romans.

The word that Aristotle uses for virtue is areté — which can also be translated as excellence. The Olympic athlete is virtuous; Nobel Prize winners are virtuous; those who embody excellence are, in this Ancient Greek sense, virtuous.

Virtue then is anything that is admirable. It’s not simply about external success. This is where the lotto winner falls down —they aren’t admired for their experience of luck. The lotto win can provide them with opportunities to be virtuous — for example by setting up a business or donating to charity — but the win isn’t inherently virtuous because luck isn’t admirable (though it is undoubtedly desirable).

The same goes for ill-gotten gains. We might have admired Elizabeth Holmes or Sam Bankman-Fried because they seemed to be brilliant minds and businesspeople but when their enterprises were revealed to be rotten to the core we realised that virtue wasn’t there. It was an illusion of virtue.

Virtue is admirability. When we feel admirable our self-esteem rises.

Because of the Default Mode Network we don’t need to be recognised for this in order to be happy. We don’t need to rely on the external scorecard of social status when we’ve got an internal meter that’s keeping score for us in-house. When we are living an admirable life our self-esteem by definition rises.

When it comes to Holmes or SBG we can see that what is admirable is not wealth. It’s not outward success. Outward success is at best a mere reflection of admirability since society is an outgrowth of humanity and thus what is esteemed by humans correlates with status in society.

But we also admire those who are not necessarily successful or high-status but those who are good parents, who display integrity, who are honest or hard-working or courageous or creative. These virtues aren’t the kind that market Capitalism rewards but being universal values, our internal scorecards do.

The virtuous life then exists on a separate axis to gain/loss and pain/pleasure. In being honest or acting with integrity we are being admirable even if we end up losing a job or a relationship. The landscape of the 3D overview sees our sense of well-being not entirely de-coupled from gain and pleasure but marching to its own drummer. More gain can enable more possibility to be virtuous but is not inherently a step towards the ultimate well-being in life that is eudaimonia.

Given this relative decoupling of gain and eudaimonia, what we have to orient ourselves by is not the outward signs of gain but the life of virtue. It is not about how much other people see our virtue. Who we are signalling to is not those outside but the judge in our head — that default network which in those idle moments wafts us with warm feelings of eudaimonia or cold feelings of depression based on its evaluation of how admirable we are.

So what is the good life? Ryan Bush boils it down to this simple equation:

E = nVs

In plain English that’s Eudaimonia, E, equals net Virtue self-signalled. That is to say that the good life can be measured by the total amount of virtue that we signal to ourselves. Or, as the ancients put it: “virtue is sufficient for eudaimonia.”

That’s everything for this instalment; if you’ve enjoyed it I’d highly recommend Ryan Bush’s book Become Who You Are which will be coming out in on the 27th of February (pre-order a copy on the Designing the Mind website here). You can also watch the long-form podcast I did with Ryan for Patreon members here.

One answer is offered by the Hedonists. They tell us that the good life is simply a question of feeling good and feeling bad. We can plot this on a simple line from pain to pleasure.; the closer you are to the pleasurable end of the scale, the better your life is.

But other philosophers aren’t satisfied by this. The trouble with this pain/pleasure map of the good life is that it lacks any relationship to consequences (which can’t be measured by a moment in time). If the good life was simply about pleasure then why not take out a bank loan and have a lot of fun — take heroin, go skydiving and party like there’s no tomorrow?

The answer is simple: because there are longer-term consequences to our actions. Today’s partying is tomorrow’s hangover.

We can map these consequences by adding another line running north-south from gain to loss. We can think of gain as pleasure extended over time — of where are pleasure is trending through time.

If our actions or experiences now trend towards a lower level of future pleasure then we can call it loss; if our actions or experiences trend towards a higher level of future pleasure then we can call it gain;

With this two-dimensional map we factor in the consequences of our actions for our future as part of our life satisfaction. We integrate the element of Time which Heidegger finds so essential to the human condition. The good life then is the convergence of pleasure in the moment and the trajectory of our lives.

But this map also runs into a wall very quickly when we consider the fate of lotto winners and paraplegics. In both of these cases we see a short-term spike in opposite directions but when asked to predict how happy they will be in a couple of years the happiness of paraplegics and lottery winners is more or less the same.

And it’s not just a property of dramatic examples. There are countless stories of people achieving their long-term goals — they bought the house or they got the promotion — and instead of feeling a burst of fulfilment they find the rug ripped from under them. These events are associated with the trope of the midlife crisis but they can happen at any point in life. The simple equation of “gain-pleasure = good life” simply doesn’t fit reality.

Eudaimonia: the third dimension

The term eudaimonia is an Ancient Greek word used by ancient philosophers like Socrates, Aristotle and the Stoics. It is sometimes translated as happiness, other times as flourishing, satisfaction or fulfilment but none of these quite captures the full meaning of the term. The best way to understand what eudaimonia is, is by looking at its much more common and familiar opposite depression.

In his book Become Who You Are — from which this video’s triple axis theory of the good life is being drawn — the author Ryan Bush outlines the four core traits to the experience of depression:

- Low mood

- Low vitality

- Low self-esteem

- Strong sense of self

By inverting these lows to highs we can form a picture of what eudaimonia is:

- High mood

- High vitality

- High self-esteem

- Strong sense of self (Note that both depression and eudaimonia share the strong sense of self — we’ll return to this point a little later.)

How to Eudaimonia

The natural next question is: how do we reach eudaimonia? It’s fairly obvious that we reach pleasure by increasing our positive emotions and that we increase gain by improving our circumstances but how exactly do we move towards eudaimonia and away from depression?

With the pop culture portrayal of depression as sadness and lethargy we might think that pleasure might be the solution but while this may temporarily impact the first and second components of depression i.e. low mood and low vitality, the effect will be short-lived.

That is because low mood and low vitality are symptoms. The deeper cause is the third component: low self-esteem. We can shoot the arrows of pleasure high in the sky but the gravity of depression’s low self-esteem will drag our mood and vitality back to the level of our self-esteem. This z-axis of depression/eudaimonia is the hidden force of gravity that pulls lotto winners and paraplegics back into alignment with each other. And so if we wish to become happier then it is towards this deeper root that we must direct our attention.

On this front we have two options. We can try to change component three — our low-self-esteem — or we can go after component four — depression’s strong sense of self.

The Spiritual Path: happiness by non-attachment

In the latter case we can reduce our experience of depression by weakening our sense of self. This is the path of spirituality. The ego as the spiritual writers tell us, is the source of all human misery. Hence by destroying —or to put it more spiritually by transcending — the ego we can reach a state of deep content away from the nagging voice of the monkey-mind ego.

But there is a white lie in the spiritual account.

In Become Who You Are, Bush presents a suitable analogy for this:

Imagine you are at home one cold winter night and you have a HVAC unit which is capable of being both a radiator and an air conditioner. Anyway this one cold night the unit malfunctions and instead of giving out lovely warm air it starts blowing out freezing cold air.

You don’t know anything about how to repair one of these things and meanwhile your room is growing increasingly unliveable by the minute.

You can take a chance on trying to figure out how to repair the thing; if you are successful you will have a very nice situation. Or you could take a golf club to the unit and in so doing destroy any chance of getting some warm air coming out but by the same token the room doesn’t get any colder. Do you try and fix the machine? Or do you destroy it and accept reality as it is?

The spiritual path in this (admittedly rather loaded) analogy is the way of the golf club. You destroy the unit and abandon your strong sense of self in order to form a relationship with reality as it is.

So much for the attack on component four. If we are not looking to go after our strong sense of self then it seems the best path forward is via component three: improving our self-esteem.

The Neuroscience of Self-Esteem

Before we look at how we do this let’s first examine Bush’s account of the neuroscience of self-esteem.

The Default Mode Network is a network of centres across the brain including the medial Pre-Frontal Cortex, the posterior cingulate cortex, the precuneus, and the angular gyrus.

The Default Mode Network is best known for being active when we are not focussed on the outside world for example when we are daydreaming or when our minds are wandering — hence the “default” in Default Mode Network.

When we are engaged in a task the Default Mode Network is usually downregulated; but rather tellingly if the task that we are engaged in is a self-oriented task like reflecting on something from our past or thinking about our future then the network lights up.

Some areas of the Default Mode Network control the release of serotonin which is connected in with our sense of relative status and value of ourselves and others. Another key subsystem is responsible for our ability to take the perspective of others and get inside what they are thinking and feeling.

What emerges is a brain network that is fundamental to our self-esteem — something which a 2016 paper by a Chinese team in Chongqing made explicit when they concluded that “[Trait Self-Esteem] is linked to core regions in the default mode network”.

Another group of researchers, Davey et al in 2016 went a step further and suggested that the Default Mode Network is the neurological basis for the conscious awareness of the self. All of this fits nicely with those studies which have found meditation decreases activity in the Default Mode Network and that psychedelics interrupt activity in this network as well.

We can see then that our destruction of the HVAC unit in the analogy earlier is neuroscientifically speaking the de-emphasis on the central importance of the Default Mode Network. Meditation takes us out of this monkey mind and psychedelics can bring about an ego death through the disruption of this network.

All of this fits well with the idea that the Default Mode Network is the centre of our self-esteem in the brain and that the path of spirituality works by weakening this sense of self rather than improving it i.e. taking a bat to the HVAC machine.

So how do we fix the HVAC machine? How do we raise our self-esteem so that we are warmed by the tropical air of eudaimonia rather than frozen by the cold air of depression?

The answer will sound strange to the 21st-century ear but would sound commonplace to an Ancient Greek or Roman ear. The answer is virtue.

Virtue: the royal road to Eudaimonia

The beating heart of Stoicism — one that is more or less absent from the 21st-century Neo-Stoic revival — is the Stoic axiom that “virtue is sufficient for happiness/eudaimonia”. When Socrates chose death over an escape into exile via bribery, he was choosing virtue. When Cato the Younger chose Civil War in Ancient Rome over compromise with Caesar’s tyranny he was choosing virtue. When Diogenes was hugging icy statues or whacking off in the marketplace he was choosing a life of virtue.

Virtue sounds prudish and self-righteous to the 21st-century ear. It is more commonly heard in the phrase “virtue signalling” as a way of criticising performative moralising than it is in the context of the good life. But it was not this way for the Greeks and Romans.

The word that Aristotle uses for virtue is areté — which can also be translated as excellence. The Olympic athlete is virtuous; Nobel Prize winners are virtuous; those who embody excellence are, in this Ancient Greek sense, virtuous.

Virtue then is anything that is admirable. It’s not simply about external success. This is where the lotto winner falls down —they aren’t admired for their experience of luck. The lotto win can provide them with opportunities to be virtuous — for example by setting up a business or donating to charity — but the win isn’t inherently virtuous because luck isn’t admirable (though it is undoubtedly desirable).

The same goes for ill-gotten gains. We might have admired Elizabeth Holmes or Sam Bankman-Fried because they seemed to be brilliant minds and businesspeople but when their enterprises were revealed to be rotten to the core we realised that virtue wasn’t there. It was an illusion of virtue.

Virtue is admirability. When we feel admirable our self-esteem rises.

Because of the Default Mode Network we don’t need to be recognised for this in order to be happy. We don’t need to rely on the external scorecard of social status when we’ve got an internal meter that’s keeping score for us in-house. When we are living an admirable life our self-esteem by definition rises.

When it comes to Holmes or SBG we can see that what is admirable is not wealth. It’s not outward success. Outward success is at best a mere reflection of admirability since society is an outgrowth of humanity and thus what is esteemed by humans correlates with status in society.

But we also admire those who are not necessarily successful or high-status but those who are good parents, who display integrity, who are honest or hard-working or courageous or creative. These virtues aren’t the kind that market Capitalism rewards but being universal values, our internal scorecards do.

The virtuous life then exists on a separate axis to gain/loss and pain/pleasure. In being honest or acting with integrity we are being admirable even if we end up losing a job or a relationship. The landscape of the 3D overview sees our sense of well-being not entirely de-coupled from gain and pleasure but marching to its own drummer. More gain can enable more possibility to be virtuous but is not inherently a step towards the ultimate well-being in life that is eudaimonia.

Given this relative decoupling of gain and eudaimonia, what we have to orient ourselves by is not the outward signs of gain but the life of virtue. It is not about how much other people see our virtue. Who we are signalling to is not those outside but the judge in our head — that default network which in those idle moments wafts us with warm feelings of eudaimonia or cold feelings of depression based on its evaluation of how admirable we are.

So what is the good life? Ryan Bush boils it down to this simple equation:

E = nVs

In plain English that’s Eudaimonia, E, equals net Virtue self-signalled. That is to say that the good life can be measured by the total amount of virtue that we signal to ourselves. Or, as the ancients put it: “virtue is sufficient for eudaimonia.”

That’s everything for this instalment; if you’ve enjoyed it I’d highly recommend Ryan Bush’s book Become Who You Are which will be coming out in on the 27th of February (pre-order a copy on the Designing the Mind website here). You can also watch the long-form podcast I did with Ryan for Patreon members here.

One answer is offered by the Hedonists. They tell us that the good life is simply a question of feeling good and feeling bad. We can plot this on a simple line from pain to pleasure.; the closer you are to the pleasurable end of the scale, the better your life is.

But other philosophers aren’t satisfied by this. The trouble with this pain/pleasure map of the good life is that it lacks any relationship to consequences (which can’t be measured by a moment in time). If the good life was simply about pleasure then why not take out a bank loan and have a lot of fun — take heroin, go skydiving and party like there’s no tomorrow?

The answer is simple: because there are longer-term consequences to our actions. Today’s partying is tomorrow’s hangover.

We can map these consequences by adding another line running north-south from gain to loss. We can think of gain as pleasure extended over time — of where are pleasure is trending through time.

If our actions or experiences now trend towards a lower level of future pleasure then we can call it loss; if our actions or experiences trend towards a higher level of future pleasure then we can call it gain;

With this two-dimensional map we factor in the consequences of our actions for our future as part of our life satisfaction. We integrate the element of Time which Heidegger finds so essential to the human condition. The good life then is the convergence of pleasure in the moment and the trajectory of our lives.

But this map also runs into a wall very quickly when we consider the fate of lotto winners and paraplegics. In both of these cases we see a short-term spike in opposite directions but when asked to predict how happy they will be in a couple of years the happiness of paraplegics and lottery winners is more or less the same.

And it’s not just a property of dramatic examples. There are countless stories of people achieving their long-term goals — they bought the house or they got the promotion — and instead of feeling a burst of fulfilment they find the rug ripped from under them. These events are associated with the trope of the midlife crisis but they can happen at any point in life. The simple equation of “gain-pleasure = good life” simply doesn’t fit reality.

Eudaimonia: the third dimension

The term eudaimonia is an Ancient Greek word used by ancient philosophers like Socrates, Aristotle and the Stoics. It is sometimes translated as happiness, other times as flourishing, satisfaction or fulfilment but none of these quite captures the full meaning of the term. The best way to understand what eudaimonia is, is by looking at its much more common and familiar opposite depression.

In his book Become Who You Are — from which this video’s triple axis theory of the good life is being drawn — the author Ryan Bush outlines the four core traits to the experience of depression:

- Low mood

- Low vitality

- Low self-esteem

- Strong sense of self

By inverting these lows to highs we can form a picture of what eudaimonia is:

- High mood

- High vitality

- High self-esteem

- Strong sense of self (Note that both depression and eudaimonia share the strong sense of self — we’ll return to this point a little later.)

How to Eudaimonia

The natural next question is: how do we reach eudaimonia? It’s fairly obvious that we reach pleasure by increasing our positive emotions and that we increase gain by improving our circumstances but how exactly do we move towards eudaimonia and away from depression?

With the pop culture portrayal of depression as sadness and lethargy we might think that pleasure might be the solution but while this may temporarily impact the first and second components of depression i.e. low mood and low vitality, the effect will be short-lived.

That is because low mood and low vitality are symptoms. The deeper cause is the third component: low self-esteem. We can shoot the arrows of pleasure high in the sky but the gravity of depression’s low self-esteem will drag our mood and vitality back to the level of our self-esteem. This z-axis of depression/eudaimonia is the hidden force of gravity that pulls lotto winners and paraplegics back into alignment with each other. And so if we wish to become happier then it is towards this deeper root that we must direct our attention.

On this front we have two options. We can try to change component three — our low-self-esteem — or we can go after component four — depression’s strong sense of self.

The Spiritual Path: happiness by non-attachment

In the latter case we can reduce our experience of depression by weakening our sense of self. This is the path of spirituality. The ego as the spiritual writers tell us, is the source of all human misery. Hence by destroying —or to put it more spiritually by transcending — the ego we can reach a state of deep content away from the nagging voice of the monkey-mind ego.

But there is a white lie in the spiritual account.

In Become Who You Are, Bush presents a suitable analogy for this:

Imagine you are at home one cold winter night and you have a HVAC unit which is capable of being both a radiator and an air conditioner. Anyway this one cold night the unit malfunctions and instead of giving out lovely warm air it starts blowing out freezing cold air.

You don’t know anything about how to repair one of these things and meanwhile your room is growing increasingly unliveable by the minute.

You can take a chance on trying to figure out how to repair the thing; if you are successful you will have a very nice situation. Or you could take a golf club to the unit and in so doing destroy any chance of getting some warm air coming out but by the same token the room doesn’t get any colder. Do you try and fix the machine? Or do you destroy it and accept reality as it is?

The spiritual path in this (admittedly rather loaded) analogy is the way of the golf club. You destroy the unit and abandon your strong sense of self in order to form a relationship with reality as it is.

So much for the attack on component four. If we are not looking to go after our strong sense of self then it seems the best path forward is via component three: improving our self-esteem.

The Neuroscience of Self-Esteem

Before we look at how we do this let’s first examine Bush’s account of the neuroscience of self-esteem.

The Default Mode Network is a network of centres across the brain including the medial Pre-Frontal Cortex, the posterior cingulate cortex, the precuneus, and the angular gyrus.

The Default Mode Network is best known for being active when we are not focussed on the outside world for example when we are daydreaming or when our minds are wandering — hence the “default” in Default Mode Network.

When we are engaged in a task the Default Mode Network is usually downregulated; but rather tellingly if the task that we are engaged in is a self-oriented task like reflecting on something from our past or thinking about our future then the network lights up.

Some areas of the Default Mode Network control the release of serotonin which is connected in with our sense of relative status and value of ourselves and others. Another key subsystem is responsible for our ability to take the perspective of others and get inside what they are thinking and feeling.

What emerges is a brain network that is fundamental to our self-esteem — something which a 2016 paper by a Chinese team in Chongqing made explicit when they concluded that “[Trait Self-Esteem] is linked to core regions in the default mode network”.

Another group of researchers, Davey et al in 2016 went a step further and suggested that the Default Mode Network is the neurological basis for the conscious awareness of the self. All of this fits nicely with those studies which have found meditation decreases activity in the Default Mode Network and that psychedelics interrupt activity in this network as well.

We can see then that our destruction of the HVAC unit in the analogy earlier is neuroscientifically speaking the de-emphasis on the central importance of the Default Mode Network. Meditation takes us out of this monkey mind and psychedelics can bring about an ego death through the disruption of this network.

All of this fits well with the idea that the Default Mode Network is the centre of our self-esteem in the brain and that the path of spirituality works by weakening this sense of self rather than improving it i.e. taking a bat to the HVAC machine.

So how do we fix the HVAC machine? How do we raise our self-esteem so that we are warmed by the tropical air of eudaimonia rather than frozen by the cold air of depression?

The answer will sound strange to the 21st-century ear but would sound commonplace to an Ancient Greek or Roman ear. The answer is virtue.

Virtue: the royal road to Eudaimonia

The beating heart of Stoicism — one that is more or less absent from the 21st-century Neo-Stoic revival — is the Stoic axiom that “virtue is sufficient for happiness/eudaimonia”. When Socrates chose death over an escape into exile via bribery, he was choosing virtue. When Cato the Younger chose Civil War in Ancient Rome over compromise with Caesar’s tyranny he was choosing virtue. When Diogenes was hugging icy statues or whacking off in the marketplace he was choosing a life of virtue.

Virtue sounds prudish and self-righteous to the 21st-century ear. It is more commonly heard in the phrase “virtue signalling” as a way of criticising performative moralising than it is in the context of the good life. But it was not this way for the Greeks and Romans.

The word that Aristotle uses for virtue is areté — which can also be translated as excellence. The Olympic athlete is virtuous; Nobel Prize winners are virtuous; those who embody excellence are, in this Ancient Greek sense, virtuous.

Virtue then is anything that is admirable. It’s not simply about external success. This is where the lotto winner falls down —they aren’t admired for their experience of luck. The lotto win can provide them with opportunities to be virtuous — for example by setting up a business or donating to charity — but the win isn’t inherently virtuous because luck isn’t admirable (though it is undoubtedly desirable).

The same goes for ill-gotten gains. We might have admired Elizabeth Holmes or Sam Bankman-Fried because they seemed to be brilliant minds and businesspeople but when their enterprises were revealed to be rotten to the core we realised that virtue wasn’t there. It was an illusion of virtue.

Virtue is admirability. When we feel admirable our self-esteem rises.

Because of the Default Mode Network we don’t need to be recognised for this in order to be happy. We don’t need to rely on the external scorecard of social status when we’ve got an internal meter that’s keeping score for us in-house. When we are living an admirable life our self-esteem by definition rises.

When it comes to Holmes or SBG we can see that what is admirable is not wealth. It’s not outward success. Outward success is at best a mere reflection of admirability since society is an outgrowth of humanity and thus what is esteemed by humans correlates with status in society.

But we also admire those who are not necessarily successful or high-status but those who are good parents, who display integrity, who are honest or hard-working or courageous or creative. These virtues aren’t the kind that market Capitalism rewards but being universal values, our internal scorecards do.

The virtuous life then exists on a separate axis to gain/loss and pain/pleasure. In being honest or acting with integrity we are being admirable even if we end up losing a job or a relationship. The landscape of the 3D overview sees our sense of well-being not entirely de-coupled from gain and pleasure but marching to its own drummer. More gain can enable more possibility to be virtuous but is not inherently a step towards the ultimate well-being in life that is eudaimonia.

Given this relative decoupling of gain and eudaimonia, what we have to orient ourselves by is not the outward signs of gain but the life of virtue. It is not about how much other people see our virtue. Who we are signalling to is not those outside but the judge in our head — that default network which in those idle moments wafts us with warm feelings of eudaimonia or cold feelings of depression based on its evaluation of how admirable we are.

So what is the good life? Ryan Bush boils it down to this simple equation:

E = nVs

In plain English that’s Eudaimonia, E, equals net Virtue self-signalled. That is to say that the good life can be measured by the total amount of virtue that we signal to ourselves. Or, as the ancients put it: “virtue is sufficient for eudaimonia.”

That’s everything for this instalment; if you’ve enjoyed it I’d highly recommend Ryan Bush’s book Become Who You Are which will be coming out in on the 27th of February (pre-order a copy on the Designing the Mind website here). You can also watch the long-form podcast I did with Ryan for Patreon members here.