“the problem of the Ufos is, as you rightly say, a very fascinating one, but it is as puzzling as it is fascinating; since, in spite of all observations I know of, there is no certainty about their very nature. On the other side, there is an overwhelming material pointing to their legendary or mythological aspect. As a matter of fact the psychological aspect is so impressive, that one almost must regret that the Ufos seem to be real after all.”

— In a 1957 letter about UFOs Carl Jung

The idea of an impending end of the world is an idea that just won’t die. To the sceptical atheistic mind this idea of Judgement Day seems like an artefact of magical thinking that should have faded with the decline of religion and the rise of secular society. But this most secular century and a half in history has been characterised by a more urgent, more strongly apocalyptic set of myths than any culture preceding it.

In the late 19th century there was Marx’s fervent prophecy of the imminent and inevitable revolution of the Proletariat. We’ve had wars to end all wars, threats of imminent nuclear annihilation, and, in the 21st century, a terror of ecological catastrophe hanging over us while the Rapture of the Nerds (aka the Singularity) sits like a mirage on the near horizon. We even have a Doomsday Clock, which, in its 70-something years, has never been more than 17 minutes from midnight.

And it’s not just in our lived reality of politics and current affairs. Our collective cultural dreaming provides hundreds of very successful examples from TV shows like The Last of Us, The Walking Dead, Black Mirror and The Handmaid’s Tale to movies like Cloud Atlas, Resident Evil, Alien and Planet of the Apes and video games like Fallout, Gears of War and Mad Max.

The secular age has been an age of apocalyptic thinking. Never has religion been so far from the mainstream and the end of the world so close. There is something in this idea that bewitches us. In this instalment we are going to separate the objective status of these apocalyptic predictions and instead focus on the possibility that humanity has a psychological need for apocalypse. This isn’t to deny the reality of these doomsday predictions but merely to comment on their peculiar recurrence. To paraphrase Jung “the psychological aspect is so impressive, that one almost must regret that the apocalypse(s) seem to be real after all”.

We are going to set aside the objective truth of these apocalyptic predictions and hone in on the psychological element at play in apocalyptic thinking and see if there isn’t something about the idea of the end game that nourishes a deep need in our culture and perhaps all human culture. But first let’s talk a little more about this tradition of secular apocalypse.

Secular Apocalypse

Doomsday is the kind of thing we might expect atheistic secular culture to categorise as infantile superstition. But despite the decline of religious belief, not only has the idea of apocalypse not disappeared — it has intensified.

Within a century of the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, the world had lived through two apocalyptic wars. These wars as it turns out were only the prelude to the greatest era of apocalyptic thinking the world has ever seen: the Cold War. With the detonation of the first nuclear warhead in Los Alamos, New Mexico, the age of imminent apocalypse began. The architect of this shift, one of science’s most brilliant minds, Robert Oppenheimer appropriately echoed the apocalyptic words of the Hindu scriptural text — the Bhagavad Gita — saying

“Now I am become death the destroyer of worlds”.

And this was the shadow the world lived in for the next half a century. We even had the Doomsday Clock and much like Jesus’s words in the Gospel of Mark:

“Some of you standing here will not taste death before they see that the Kingdom of God has come in power” (Mark 9:1)

the secular era has lived under the imminent shadow of the world’s end.

This justified spate of secular apocalyptic thinking wound down with the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. The threat of nuclear annihilation faded into the background. Of course that’s not to say that danger was gone only that it was no longer an impending psychic shadow hanging over everyone.

And so it seemed that secular civilisation could do away with the idea of the end of the world. But this wasn’t to be. Within the decade people began fearing for Y2K and a few years after that the new age of secular apocalypticism exploded onto the scene.

Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth was released in 2006 and this was the real watershed moment for the end of the world crisis that grips our present era’s collective psyche. Over the past decade and a half the shade of this apocalypse has grown in intensity. Like the Incel and the Social Justice Warrior, the Doomer has become one of the meme identities of the 21st century. This new identity and its connected trends of Doomsday Prepping and Antinatalism has revealed itself to be a powerful cultural meme in the Dawkinsian sense of the word.

And the climate crisis isn’t the only active secular apocalypse on the table. We still have the threat of another world war and with it of nuclear annihilation; there have been a number of New Age predictions of the end (most famously 2012 but also 2011 and 2021) and there’s a growing eschatological movement to be found in the Technological Singularity. As well as these there’s fears about overpopulation, about demographic collapse and about the fall of the global civilisation.

In short the emergence of secular culture from the husk of religious thinking has not brought an end to apocalyptic thinking but an augmentation of it.

Again let me reiterate that this article isn’t a dismissal of the apocalypses facing us as mere psychological artefacts. Nuclear arsenals exist and the climate crisis is an overwhelming danger. But like Jung does with UFOs it is important to parse the psychological element (to ‘bracket’ in the language of the Phenomenologists) from the reality principle because something is going on in the human psyche — a carousel of catastrophising — that is an extra layer coating the realities we are facing. The question I want to ask is this: what role does the end of the world play in the collective psyche? Why do we have a seemingly imminent psychological need for the end of the world?

A History of Prediction

There is a rich historical tradition of imminent doomsday predictions. This Wikipedia page lists 168 such predictions. which are, for the most part, Christian predictions of the return of Christ and the coming of Judgement Day.

Looking through the 168 predictions, the distinction between Christian and non-Christian predictions immediately jumps out especially as we enter the modern age. But there’s another distinction worth noting. If we look at the prophets of this apocalypse we of course find the usual suspects like Jim Jones or the tele-evangelist types and their more old-school counterparts like Nostradamus. This group of prophets would be categorised today as cranks. But there’s another group that is a little more surprising. There are names that really jump out like Pope Innocent III, Pope Sylvester II, Protestant church founders Martin Luther and John Wesley and we even have an appearance from Christopher Columbus.

So, much like our own time, Apocalyptic mythology isn’t just a quality of the fringe and disillusioned, it is often a myth that is held at the core of Western culture. In this sense the predictions of these prominent figures dovetails well with the secular apocalyptic phenomena like nuclear annihilation and climate change.

Apocalyptic Themes

1. The Calendrical Apocalypse

Looking through the list of predictions, there are two major patterns pointing to two separate elements of our psychology.

The first major theme is the calendar. Dozens of these historical predictions are based on significant dates. That this would be particularly acute in the Christian cultural sphere is unsurprising given the nature of Jesus’s teachings. In his book Jesus Interrupted Biblical scholar Bart Ehrman writes:

“For over a century now, since the landmark publication of Albert Schweitzer’s masterpiece, The Quest of the Historical Jesus, the majority of scholars in Europe and North America have understood Jesus as a Jewish apocalyptic prophet”

“The early Christians, like Jesus before them, and John the Baptist before him, were apocalyptically minded Jews, expecting the imminent end of the age.”

In the Gospel of Mark, Matthew and Luke, Jesus predicts that before many of those he’s talking to die, the kingdom of heaven will have arrived. As he put it in the Gospel of Mark:

“Some of you standing here will not taste death before they see that the Kingdom of God has come in power” (Mark 9:1)

When this prophecy failed to come to fruition, the scholars of prophecy did what they always do: they shifted the goalposts. When we come to the first millennium there’s a surge of Doomsday predictions that crop up. It started with the millennium itself and then it was pushed out 33 years to be a thousand years after the resurrection. There were similar predictions with the second millennium in 2000.

Columbus’s prophecy, along with those of several other prophets, was based on a reading of Biblical history. He believed that the world would end 7000 years after creation which by his reckoning was 1658.

This fascination with the calendar isn’t tethered to Christianity — though it does seem to be tied to Christian cultures. The two major examples in this vein are the supposed end of the Mayan Long Count calendar in December 2012 and the prophesied end of the age of computers with Y2K in 2000.

In summary then, this first category of Doomsday prophecy seems to be a Western Christian tradition. It’s not clear why the Christian culture should be more fascinated with this form of apocalypse than other cultures. Obviously the Christian emphasis on Apocalypse in the New Testament lays a solid groundwork but despite this also being a key element of the Islamic tradition it is almost unheard of in that tradition to try and pin the end of the world on a specific year. This may have something to do with the nature of the calendar since the Western Gregorian calendar is solar while the Islamic calendar is lunar. The entirely solar character of the Gregorian calendar (and the Julian calendar before it) may be significant in general in this regard if we think of the lunar calendar of Islam and the hybrid lunisolar calendars common elsewhere.

This vein of apocalyptic thinking has a separate psychological footprint and aside from Y2K it is much less common in the secular tradition of apocalypse so let’s move on to the more universal theme in humanity’s apocalyptic thinking.

2. The Chaotic Womb of Apocalypse

The more universal apocalyptic tradition has nothing to do with the calendar and is a tradition with a rich history inside and outside of Western history.

In 2015 The Diplomat published an article titled The Apocalypse Psyche: A Look at Chinese Eschatology. Eschatology is a technical theological term which the Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines as:

1: a branch of theology concerned with the final events in the history of the world or of humankind 2: a belief concerning death, the end of the world, or the ultimate destiny of humankind

This article in The Diplomat looks at the political role of eschatological thinking in the history of China:

In China, an apocalypse best highlights the shift in power and the birth of a new form of governance.

The article talks about a Taoist text written in the 5th century AD called The Divine Incantations Scripture (太上洞渊神咒经) which speaks about

“the return of a messianic figure who will take the faithful and destroy the rest of society and create a new society based upon Taoist teachings.”

A few centuries earlier the idea of Apocalypse was used to undermine the Han Dynasty during the Yellow Turban Rebellion of 184–205 AD. At this time many Taoists proclaimed that the inequality of the time — when “the massive peasant classes worked for a pittance and faced heavy taxation” — would end in a period of destruction out of which a new order of society would be reborn.

Moving westward, the Pew Research Centre conducted a poll in 2012 among Muslims across the world from East Asia to Sub-Saharan Africa and Europe. This poll asked participants about their belief in a number of Muslim doctrines. The poll found that 50% or more of respondents in a number of Muslim-majority countries expected the Mahdi (the final redeemer according to Islam) to return during their lifetime. The countries where this belief was highest were Afghanistan where 83% believed this and Iraq where 72% believed this. When we connect the American invasions of these countries in the decade preceding this poll and The Diplomat author’s connection between apocalyptic thinking and social upheaval, the psychology underpinning these numbers becomes less surprising.

Chaos in Western History

The same pattern shows up throughout history.

Jesus’s doomsday work — along with John the Baptist before him and Paul after him — can be seen against the backdrop of the Roman conquest of Israel and of the Western world in general. Israel had become a part of Rome just sixty years before Jesus’s birth and in that time there had been two civil wars and a transformation of Rome from a republic into an empire. Three decades after Jesus’s death there began the Jewish-Roman wars during which the Second Temple was destroyed.

In England’s 17th century civil wars there were fervent apocalyptic expectations among radical parliamentary sects that were shared by the likes of Oliver Cromwell and John Milton.

In the late 18th century the French Revolution triggered an even greater deluge of apocalyptic feeling. There was a surge of preachers who interpreted events in France in terms of Biblical prophecies. In 1791 Thomas Holcroft wrote:

“Hey for the New Jerusalem! The millennium!”

The Romantic poets of England all got caught up in this fury. During the French Revolution Coleridge summarised his expectation as:

“The French Revolution. Millennium. Universal Redemption. Conclusion.”

Blake speaks of a revolutionary “son of fire” moving from America to France and heralding a new age:

“Empire is no more! and now the lion & wolf shall cease”

Meanwhile Wordsworth in the concluded 1793’s Descriptive Sketches with the enthusiastic prophecy that the French Revolution was the beginning of the fulfilment of the Book of Revelation.

The Chaotic 19th Century

Of course the language of apocalypse at this time is still very recognisably Christian and couched in the Christian worldview. But as we enter the middle of the 19th century and the death of God begins in Germany with works like The Life of Jesus by David Strauss uncovering the historical Jesus and then on the other hand Darwin’s work on evolution being published things begin to take a turn for the atheistic.

The 19th century was a time of dramatic social upheaval. This was the time when Europe as a whole was moving from the age of Feudalism into the age of industrialised modernity. Capitalism was beginning its takeover of the world.

This liminal period brought with it idealistic dreams and terrifying realities. This was the peak of Utopian Socialist thinking and it was a time of revolution. In the 1820s there were revolutions in Spain, Portugal, Greece and Russia. In the 1830s there were revolutions in Belgium, France, Italy, Poland, Portugal and Switzerland. The European pressure cooker exploded in 1848. This momentous year saw a wave of revolutions spread across Europe — the greatest wave of revolutions the continent has ever seen. It began in Sicily then France and from there it spread across the entire continent with the exceptions of Russia, Spain, and the Scandinavian countries.

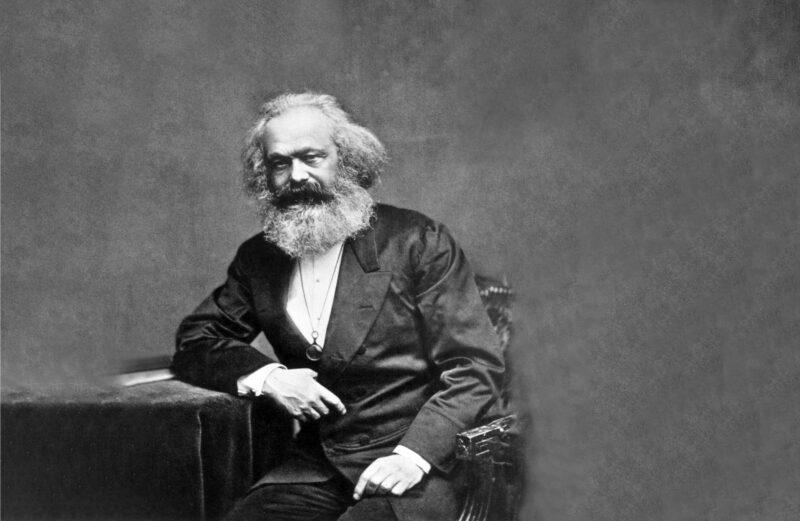

It is against the backdrop of these decades of revolution that Marxism was born. At the core of Marx’s thinking was the prophecy of the uprising of the proletariat. Marx was working off a Hegelian vision of history in which history’s progression is seen much like the butterfly’s evolution from the caterpillar. When Marx first moved to London in 1849 he believed the next phase of historical evolution was imminent — that widespread Proletarian revolution across the continent was imminent. He and Engels made prediction after prediction for this revolution until ultimately Marx had to accept that it might not come immediately.

Nevertheless, his whole career he continued to believe in the inevitable toppling of Capitalism by Communism. It was as inevitable as the summer following the spring. This prophecy was at the heart of the Marxist spirit and drove the revolutionary movement into the 20th century.

The Cold War with its climate of nuclear apocalypse had a similar backdrop with the two wars to end all wars.

The Chaotic 21st Century

And with the 21st century the upheaval of life continues at a social level. The economic and social disruption of Neoliberalism and digital life has led to a disruption of all stability. As rapid transformation has taken over, the apocalyptic rhetoric has increased in shrillness once again.

The appropriately named Millennials and the Generation Z that follow them are growing up in a world of incredible abundance but find that in many ways they have missed the party. The cost of entry to the party has left millions saddled with unmanageable debt. This combined with the skyrocketing cost of property and with university education becoming a (very expensive) commonplace, generations of discontented and disenfranchised youth without the crippling demands to feed themselves have become conscious of a raw deal.

The end of the world in this scenario gives urgency and archetypal charge to the idea of a climate crisis.

Inheriting a world with high entry costs, the environment plundered and a ticking timer attached has created a breeding ground for discontent with the system. As the Bourbons learned with the French Revolution, when the wealth disparity reaches extremes and the lower classes feel cheated, they feel they have nothing to lose by toppling the system. This is the feeling of many Millennials and Gen Z today.

This might be one explanation for why the climate crisis has become such a politically charged issue. It is the end of the world scenario that gives an eschatological urgency to the social problems felt by the Millennials. It is a bludgeon of rebuttal that can be wielded by a disaffected class. In the past, such social unrest has led to the formation of Islam and the wars that surrounded it; the creation of Christianity; and the terrors of the French Revolution.

The end of the world in this scenario gives urgency and archetypal charge to the idea of a climate crisis.

Examining the psychological fervour around the Climate Crisis we can see one of the universal patterns of human history: when the world changes the archetypal unconscious of humanity vomits into the everyday world. As with all archetypal eruptions, it is bipolar. As the social upheaval at the emergence of Islam and Christianity brought a divine revelation of hope it also brought with it a terrifying end to history. The same goes for the Taoist myths in Ancient China.

We find this same pattern recurring throughout the secular age of modernity. In the 19th century there were dreams of a Utopian world where the Kingdom of Heaven would finally find its home on Earth. But with these visions of greatness there emerged a vision of a holy war between the classes that would be needed to bring about this transition. In the 21st century political instability has brought visions of horror with Climate Change but also dreams of a Socialist future in the leftist camps and the vision of techno-utopia that is the Singularity in the nerd camp.

There are still many questions to be asked and answered as to the nature of this psychological need for apocalypse. We might ask whether such attitudes are the laying bare of human biases when their model of the world breaks down. We might wonder whether there is an evolutionary component and whether such an archetypal splitting of utopian and dystopian thinking is adaptive to creating new order out of the disintegration of the social chaos. I suspect that this psychology can be meaningfully illuminated by the anthropological idea of Liminality which we will be covering in a future instalment.

For now I hope this article has provoked some thought and added a new way of looking at events in the world and offers the possibility of seeing the psychological shadows of the ages separate from the topical content of the day. Once again none of this psychological dissection is meant to detract from the reality of the crises that face us. It is merely a way of sobering us up from archetypal intoxication so that we are more able to communicate and cooperate rather than playing out archetypal dramas. This seems to be something of a theme on the channel and it brings to mind the instalment on the Jordan Peterson and Olivia Wilde debacle.

One Comment

Leave A Comment

“the problem of the Ufos is, as you rightly say, a very fascinating one, but it is as puzzling as it is fascinating; since, in spite of all observations I know of, there is no certainty about their very nature. On the other side, there is an overwhelming material pointing to their legendary or mythological aspect. As a matter of fact the psychological aspect is so impressive, that one almost must regret that the Ufos seem to be real after all.”

— In a 1957 letter about UFOs Carl Jung

The idea of an impending end of the world is an idea that just won’t die. To the sceptical atheistic mind this idea of Judgement Day seems like an artefact of magical thinking that should have faded with the decline of religion and the rise of secular society. But this most secular century and a half in history has been characterised by a more urgent, more strongly apocalyptic set of myths than any culture preceding it.

In the late 19th century there was Marx’s fervent prophecy of the imminent and inevitable revolution of the Proletariat. We’ve had wars to end all wars, threats of imminent nuclear annihilation, and, in the 21st century, a terror of ecological catastrophe hanging over us while the Rapture of the Nerds (aka the Singularity) sits like a mirage on the near horizon. We even have a Doomsday Clock, which, in its 70-something years, has never been more than 17 minutes from midnight.

And it’s not just in our lived reality of politics and current affairs. Our collective cultural dreaming provides hundreds of very successful examples from TV shows like The Last of Us, The Walking Dead, Black Mirror and The Handmaid’s Tale to movies like Cloud Atlas, Resident Evil, Alien and Planet of the Apes and video games like Fallout, Gears of War and Mad Max.

The secular age has been an age of apocalyptic thinking. Never has religion been so far from the mainstream and the end of the world so close. There is something in this idea that bewitches us. In this instalment we are going to separate the objective status of these apocalyptic predictions and instead focus on the possibility that humanity has a psychological need for apocalypse. This isn’t to deny the reality of these doomsday predictions but merely to comment on their peculiar recurrence. To paraphrase Jung “the psychological aspect is so impressive, that one almost must regret that the apocalypse(s) seem to be real after all”.

We are going to set aside the objective truth of these apocalyptic predictions and hone in on the psychological element at play in apocalyptic thinking and see if there isn’t something about the idea of the end game that nourishes a deep need in our culture and perhaps all human culture. But first let’s talk a little more about this tradition of secular apocalypse.

Secular Apocalypse

Doomsday is the kind of thing we might expect atheistic secular culture to categorise as infantile superstition. But despite the decline of religious belief, not only has the idea of apocalypse not disappeared — it has intensified.

Within a century of the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, the world had lived through two apocalyptic wars. These wars as it turns out were only the prelude to the greatest era of apocalyptic thinking the world has ever seen: the Cold War. With the detonation of the first nuclear warhead in Los Alamos, New Mexico, the age of imminent apocalypse began. The architect of this shift, one of science’s most brilliant minds, Robert Oppenheimer appropriately echoed the apocalyptic words of the Hindu scriptural text — the Bhagavad Gita — saying

“Now I am become death the destroyer of worlds”.

And this was the shadow the world lived in for the next half a century. We even had the Doomsday Clock and much like Jesus’s words in the Gospel of Mark:

“Some of you standing here will not taste death before they see that the Kingdom of God has come in power” (Mark 9:1)

the secular era has lived under the imminent shadow of the world’s end.

This justified spate of secular apocalyptic thinking wound down with the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. The threat of nuclear annihilation faded into the background. Of course that’s not to say that danger was gone only that it was no longer an impending psychic shadow hanging over everyone.

And so it seemed that secular civilisation could do away with the idea of the end of the world. But this wasn’t to be. Within the decade people began fearing for Y2K and a few years after that the new age of secular apocalypticism exploded onto the scene.

Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth was released in 2006 and this was the real watershed moment for the end of the world crisis that grips our present era’s collective psyche. Over the past decade and a half the shade of this apocalypse has grown in intensity. Like the Incel and the Social Justice Warrior, the Doomer has become one of the meme identities of the 21st century. This new identity and its connected trends of Doomsday Prepping and Antinatalism has revealed itself to be a powerful cultural meme in the Dawkinsian sense of the word.

And the climate crisis isn’t the only active secular apocalypse on the table. We still have the threat of another world war and with it of nuclear annihilation; there have been a number of New Age predictions of the end (most famously 2012 but also 2011 and 2021) and there’s a growing eschatological movement to be found in the Technological Singularity. As well as these there’s fears about overpopulation, about demographic collapse and about the fall of the global civilisation.

In short the emergence of secular culture from the husk of religious thinking has not brought an end to apocalyptic thinking but an augmentation of it.

Again let me reiterate that this article isn’t a dismissal of the apocalypses facing us as mere psychological artefacts. Nuclear arsenals exist and the climate crisis is an overwhelming danger. But like Jung does with UFOs it is important to parse the psychological element (to ‘bracket’ in the language of the Phenomenologists) from the reality principle because something is going on in the human psyche — a carousel of catastrophising — that is an extra layer coating the realities we are facing. The question I want to ask is this: what role does the end of the world play in the collective psyche? Why do we have a seemingly imminent psychological need for the end of the world?

A History of Prediction

There is a rich historical tradition of imminent doomsday predictions. This Wikipedia page lists 168 such predictions. which are, for the most part, Christian predictions of the return of Christ and the coming of Judgement Day.

Looking through the 168 predictions, the distinction between Christian and non-Christian predictions immediately jumps out especially as we enter the modern age. But there’s another distinction worth noting. If we look at the prophets of this apocalypse we of course find the usual suspects like Jim Jones or the tele-evangelist types and their more old-school counterparts like Nostradamus. This group of prophets would be categorised today as cranks. But there’s another group that is a little more surprising. There are names that really jump out like Pope Innocent III, Pope Sylvester II, Protestant church founders Martin Luther and John Wesley and we even have an appearance from Christopher Columbus.

So, much like our own time, Apocalyptic mythology isn’t just a quality of the fringe and disillusioned, it is often a myth that is held at the core of Western culture. In this sense the predictions of these prominent figures dovetails well with the secular apocalyptic phenomena like nuclear annihilation and climate change.

Apocalyptic Themes

1. The Calendrical Apocalypse

Looking through the list of predictions, there are two major patterns pointing to two separate elements of our psychology.

The first major theme is the calendar. Dozens of these historical predictions are based on significant dates. That this would be particularly acute in the Christian cultural sphere is unsurprising given the nature of Jesus’s teachings. In his book Jesus Interrupted Biblical scholar Bart Ehrman writes:

“For over a century now, since the landmark publication of Albert Schweitzer’s masterpiece, The Quest of the Historical Jesus, the majority of scholars in Europe and North America have understood Jesus as a Jewish apocalyptic prophet”

“The early Christians, like Jesus before them, and John the Baptist before him, were apocalyptically minded Jews, expecting the imminent end of the age.”

In the Gospel of Mark, Matthew and Luke, Jesus predicts that before many of those he’s talking to die, the kingdom of heaven will have arrived. As he put it in the Gospel of Mark:

“Some of you standing here will not taste death before they see that the Kingdom of God has come in power” (Mark 9:1)

When this prophecy failed to come to fruition, the scholars of prophecy did what they always do: they shifted the goalposts. When we come to the first millennium there’s a surge of Doomsday predictions that crop up. It started with the millennium itself and then it was pushed out 33 years to be a thousand years after the resurrection. There were similar predictions with the second millennium in 2000.

Columbus’s prophecy, along with those of several other prophets, was based on a reading of Biblical history. He believed that the world would end 7000 years after creation which by his reckoning was 1658.

This fascination with the calendar isn’t tethered to Christianity — though it does seem to be tied to Christian cultures. The two major examples in this vein are the supposed end of the Mayan Long Count calendar in December 2012 and the prophesied end of the age of computers with Y2K in 2000.

In summary then, this first category of Doomsday prophecy seems to be a Western Christian tradition. It’s not clear why the Christian culture should be more fascinated with this form of apocalypse than other cultures. Obviously the Christian emphasis on Apocalypse in the New Testament lays a solid groundwork but despite this also being a key element of the Islamic tradition it is almost unheard of in that tradition to try and pin the end of the world on a specific year. This may have something to do with the nature of the calendar since the Western Gregorian calendar is solar while the Islamic calendar is lunar. The entirely solar character of the Gregorian calendar (and the Julian calendar before it) may be significant in general in this regard if we think of the lunar calendar of Islam and the hybrid lunisolar calendars common elsewhere.

This vein of apocalyptic thinking has a separate psychological footprint and aside from Y2K it is much less common in the secular tradition of apocalypse so let’s move on to the more universal theme in humanity’s apocalyptic thinking.

2. The Chaotic Womb of Apocalypse

The more universal apocalyptic tradition has nothing to do with the calendar and is a tradition with a rich history inside and outside of Western history.

In 2015 The Diplomat published an article titled The Apocalypse Psyche: A Look at Chinese Eschatology. Eschatology is a technical theological term which the Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines as:

1: a branch of theology concerned with the final events in the history of the world or of humankind 2: a belief concerning death, the end of the world, or the ultimate destiny of humankind

This article in The Diplomat looks at the political role of eschatological thinking in the history of China:

In China, an apocalypse best highlights the shift in power and the birth of a new form of governance.

The article talks about a Taoist text written in the 5th century AD called The Divine Incantations Scripture (太上洞渊神咒经) which speaks about

“the return of a messianic figure who will take the faithful and destroy the rest of society and create a new society based upon Taoist teachings.”

A few centuries earlier the idea of Apocalypse was used to undermine the Han Dynasty during the Yellow Turban Rebellion of 184–205 AD. At this time many Taoists proclaimed that the inequality of the time — when “the massive peasant classes worked for a pittance and faced heavy taxation” — would end in a period of destruction out of which a new order of society would be reborn.

Moving westward, the Pew Research Centre conducted a poll in 2012 among Muslims across the world from East Asia to Sub-Saharan Africa and Europe. This poll asked participants about their belief in a number of Muslim doctrines. The poll found that 50% or more of respondents in a number of Muslim-majority countries expected the Mahdi (the final redeemer according to Islam) to return during their lifetime. The countries where this belief was highest were Afghanistan where 83% believed this and Iraq where 72% believed this. When we connect the American invasions of these countries in the decade preceding this poll and The Diplomat author’s connection between apocalyptic thinking and social upheaval, the psychology underpinning these numbers becomes less surprising.

Chaos in Western History

The same pattern shows up throughout history.

Jesus’s doomsday work — along with John the Baptist before him and Paul after him — can be seen against the backdrop of the Roman conquest of Israel and of the Western world in general. Israel had become a part of Rome just sixty years before Jesus’s birth and in that time there had been two civil wars and a transformation of Rome from a republic into an empire. Three decades after Jesus’s death there began the Jewish-Roman wars during which the Second Temple was destroyed.

In England’s 17th century civil wars there were fervent apocalyptic expectations among radical parliamentary sects that were shared by the likes of Oliver Cromwell and John Milton.

In the late 18th century the French Revolution triggered an even greater deluge of apocalyptic feeling. There was a surge of preachers who interpreted events in France in terms of Biblical prophecies. In 1791 Thomas Holcroft wrote:

“Hey for the New Jerusalem! The millennium!”

The Romantic poets of England all got caught up in this fury. During the French Revolution Coleridge summarised his expectation as:

“The French Revolution. Millennium. Universal Redemption. Conclusion.”

Blake speaks of a revolutionary “son of fire” moving from America to France and heralding a new age:

“Empire is no more! and now the lion & wolf shall cease”

Meanwhile Wordsworth in the concluded 1793’s Descriptive Sketches with the enthusiastic prophecy that the French Revolution was the beginning of the fulfilment of the Book of Revelation.

The Chaotic 19th Century

Of course the language of apocalypse at this time is still very recognisably Christian and couched in the Christian worldview. But as we enter the middle of the 19th century and the death of God begins in Germany with works like The Life of Jesus by David Strauss uncovering the historical Jesus and then on the other hand Darwin’s work on evolution being published things begin to take a turn for the atheistic.

The 19th century was a time of dramatic social upheaval. This was the time when Europe as a whole was moving from the age of Feudalism into the age of industrialised modernity. Capitalism was beginning its takeover of the world.

This liminal period brought with it idealistic dreams and terrifying realities. This was the peak of Utopian Socialist thinking and it was a time of revolution. In the 1820s there were revolutions in Spain, Portugal, Greece and Russia. In the 1830s there were revolutions in Belgium, France, Italy, Poland, Portugal and Switzerland. The European pressure cooker exploded in 1848. This momentous year saw a wave of revolutions spread across Europe — the greatest wave of revolutions the continent has ever seen. It began in Sicily then France and from there it spread across the entire continent with the exceptions of Russia, Spain, and the Scandinavian countries.

It is against the backdrop of these decades of revolution that Marxism was born. At the core of Marx’s thinking was the prophecy of the uprising of the proletariat. Marx was working off a Hegelian vision of history in which history’s progression is seen much like the butterfly’s evolution from the caterpillar. When Marx first moved to London in 1849 he believed the next phase of historical evolution was imminent — that widespread Proletarian revolution across the continent was imminent. He and Engels made prediction after prediction for this revolution until ultimately Marx had to accept that it might not come immediately.

Nevertheless, his whole career he continued to believe in the inevitable toppling of Capitalism by Communism. It was as inevitable as the summer following the spring. This prophecy was at the heart of the Marxist spirit and drove the revolutionary movement into the 20th century.

The Cold War with its climate of nuclear apocalypse had a similar backdrop with the two wars to end all wars.

The Chaotic 21st Century

And with the 21st century the upheaval of life continues at a social level. The economic and social disruption of Neoliberalism and digital life has led to a disruption of all stability. As rapid transformation has taken over, the apocalyptic rhetoric has increased in shrillness once again.

The appropriately named Millennials and the Generation Z that follow them are growing up in a world of incredible abundance but find that in many ways they have missed the party. The cost of entry to the party has left millions saddled with unmanageable debt. This combined with the skyrocketing cost of property and with university education becoming a (very expensive) commonplace, generations of discontented and disenfranchised youth without the crippling demands to feed themselves have become conscious of a raw deal.

The end of the world in this scenario gives urgency and archetypal charge to the idea of a climate crisis.

Inheriting a world with high entry costs, the environment plundered and a ticking timer attached has created a breeding ground for discontent with the system. As the Bourbons learned with the French Revolution, when the wealth disparity reaches extremes and the lower classes feel cheated, they feel they have nothing to lose by toppling the system. This is the feeling of many Millennials and Gen Z today.

This might be one explanation for why the climate crisis has become such a politically charged issue. It is the end of the world scenario that gives an eschatological urgency to the social problems felt by the Millennials. It is a bludgeon of rebuttal that can be wielded by a disaffected class. In the past, such social unrest has led to the formation of Islam and the wars that surrounded it; the creation of Christianity; and the terrors of the French Revolution.

The end of the world in this scenario gives urgency and archetypal charge to the idea of a climate crisis.

Examining the psychological fervour around the Climate Crisis we can see one of the universal patterns of human history: when the world changes the archetypal unconscious of humanity vomits into the everyday world. As with all archetypal eruptions, it is bipolar. As the social upheaval at the emergence of Islam and Christianity brought a divine revelation of hope it also brought with it a terrifying end to history. The same goes for the Taoist myths in Ancient China.

We find this same pattern recurring throughout the secular age of modernity. In the 19th century there were dreams of a Utopian world where the Kingdom of Heaven would finally find its home on Earth. But with these visions of greatness there emerged a vision of a holy war between the classes that would be needed to bring about this transition. In the 21st century political instability has brought visions of horror with Climate Change but also dreams of a Socialist future in the leftist camps and the vision of techno-utopia that is the Singularity in the nerd camp.

There are still many questions to be asked and answered as to the nature of this psychological need for apocalypse. We might ask whether such attitudes are the laying bare of human biases when their model of the world breaks down. We might wonder whether there is an evolutionary component and whether such an archetypal splitting of utopian and dystopian thinking is adaptive to creating new order out of the disintegration of the social chaos. I suspect that this psychology can be meaningfully illuminated by the anthropological idea of Liminality which we will be covering in a future instalment.

For now I hope this article has provoked some thought and added a new way of looking at events in the world and offers the possibility of seeing the psychological shadows of the ages separate from the topical content of the day. Once again none of this psychological dissection is meant to detract from the reality of the crises that face us. It is merely a way of sobering us up from archetypal intoxication so that we are more able to communicate and cooperate rather than playing out archetypal dramas. This seems to be something of a theme on the channel and it brings to mind the instalment on the Jordan Peterson and Olivia Wilde debacle.

One Comment

-

Your work is a vital resource in today’s fast-paced world.

Leave A Comment

“the problem of the Ufos is, as you rightly say, a very fascinating one, but it is as puzzling as it is fascinating; since, in spite of all observations I know of, there is no certainty about their very nature. On the other side, there is an overwhelming material pointing to their legendary or mythological aspect. As a matter of fact the psychological aspect is so impressive, that one almost must regret that the Ufos seem to be real after all.”

— In a 1957 letter about UFOs Carl Jung

The idea of an impending end of the world is an idea that just won’t die. To the sceptical atheistic mind this idea of Judgement Day seems like an artefact of magical thinking that should have faded with the decline of religion and the rise of secular society. But this most secular century and a half in history has been characterised by a more urgent, more strongly apocalyptic set of myths than any culture preceding it.

In the late 19th century there was Marx’s fervent prophecy of the imminent and inevitable revolution of the Proletariat. We’ve had wars to end all wars, threats of imminent nuclear annihilation, and, in the 21st century, a terror of ecological catastrophe hanging over us while the Rapture of the Nerds (aka the Singularity) sits like a mirage on the near horizon. We even have a Doomsday Clock, which, in its 70-something years, has never been more than 17 minutes from midnight.

And it’s not just in our lived reality of politics and current affairs. Our collective cultural dreaming provides hundreds of very successful examples from TV shows like The Last of Us, The Walking Dead, Black Mirror and The Handmaid’s Tale to movies like Cloud Atlas, Resident Evil, Alien and Planet of the Apes and video games like Fallout, Gears of War and Mad Max.

The secular age has been an age of apocalyptic thinking. Never has religion been so far from the mainstream and the end of the world so close. There is something in this idea that bewitches us. In this instalment we are going to separate the objective status of these apocalyptic predictions and instead focus on the possibility that humanity has a psychological need for apocalypse. This isn’t to deny the reality of these doomsday predictions but merely to comment on their peculiar recurrence. To paraphrase Jung “the psychological aspect is so impressive, that one almost must regret that the apocalypse(s) seem to be real after all”.

We are going to set aside the objective truth of these apocalyptic predictions and hone in on the psychological element at play in apocalyptic thinking and see if there isn’t something about the idea of the end game that nourishes a deep need in our culture and perhaps all human culture. But first let’s talk a little more about this tradition of secular apocalypse.

Secular Apocalypse

Doomsday is the kind of thing we might expect atheistic secular culture to categorise as infantile superstition. But despite the decline of religious belief, not only has the idea of apocalypse not disappeared — it has intensified.

Within a century of the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, the world had lived through two apocalyptic wars. These wars as it turns out were only the prelude to the greatest era of apocalyptic thinking the world has ever seen: the Cold War. With the detonation of the first nuclear warhead in Los Alamos, New Mexico, the age of imminent apocalypse began. The architect of this shift, one of science’s most brilliant minds, Robert Oppenheimer appropriately echoed the apocalyptic words of the Hindu scriptural text — the Bhagavad Gita — saying

“Now I am become death the destroyer of worlds”.

And this was the shadow the world lived in for the next half a century. We even had the Doomsday Clock and much like Jesus’s words in the Gospel of Mark:

“Some of you standing here will not taste death before they see that the Kingdom of God has come in power” (Mark 9:1)

the secular era has lived under the imminent shadow of the world’s end.

This justified spate of secular apocalyptic thinking wound down with the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. The threat of nuclear annihilation faded into the background. Of course that’s not to say that danger was gone only that it was no longer an impending psychic shadow hanging over everyone.

And so it seemed that secular civilisation could do away with the idea of the end of the world. But this wasn’t to be. Within the decade people began fearing for Y2K and a few years after that the new age of secular apocalypticism exploded onto the scene.

Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth was released in 2006 and this was the real watershed moment for the end of the world crisis that grips our present era’s collective psyche. Over the past decade and a half the shade of this apocalypse has grown in intensity. Like the Incel and the Social Justice Warrior, the Doomer has become one of the meme identities of the 21st century. This new identity and its connected trends of Doomsday Prepping and Antinatalism has revealed itself to be a powerful cultural meme in the Dawkinsian sense of the word.

And the climate crisis isn’t the only active secular apocalypse on the table. We still have the threat of another world war and with it of nuclear annihilation; there have been a number of New Age predictions of the end (most famously 2012 but also 2011 and 2021) and there’s a growing eschatological movement to be found in the Technological Singularity. As well as these there’s fears about overpopulation, about demographic collapse and about the fall of the global civilisation.

In short the emergence of secular culture from the husk of religious thinking has not brought an end to apocalyptic thinking but an augmentation of it.

Again let me reiterate that this article isn’t a dismissal of the apocalypses facing us as mere psychological artefacts. Nuclear arsenals exist and the climate crisis is an overwhelming danger. But like Jung does with UFOs it is important to parse the psychological element (to ‘bracket’ in the language of the Phenomenologists) from the reality principle because something is going on in the human psyche — a carousel of catastrophising — that is an extra layer coating the realities we are facing. The question I want to ask is this: what role does the end of the world play in the collective psyche? Why do we have a seemingly imminent psychological need for the end of the world?

A History of Prediction

There is a rich historical tradition of imminent doomsday predictions. This Wikipedia page lists 168 such predictions. which are, for the most part, Christian predictions of the return of Christ and the coming of Judgement Day.

Looking through the 168 predictions, the distinction between Christian and non-Christian predictions immediately jumps out especially as we enter the modern age. But there’s another distinction worth noting. If we look at the prophets of this apocalypse we of course find the usual suspects like Jim Jones or the tele-evangelist types and their more old-school counterparts like Nostradamus. This group of prophets would be categorised today as cranks. But there’s another group that is a little more surprising. There are names that really jump out like Pope Innocent III, Pope Sylvester II, Protestant church founders Martin Luther and John Wesley and we even have an appearance from Christopher Columbus.

So, much like our own time, Apocalyptic mythology isn’t just a quality of the fringe and disillusioned, it is often a myth that is held at the core of Western culture. In this sense the predictions of these prominent figures dovetails well with the secular apocalyptic phenomena like nuclear annihilation and climate change.

Apocalyptic Themes

1. The Calendrical Apocalypse

Looking through the list of predictions, there are two major patterns pointing to two separate elements of our psychology.

The first major theme is the calendar. Dozens of these historical predictions are based on significant dates. That this would be particularly acute in the Christian cultural sphere is unsurprising given the nature of Jesus’s teachings. In his book Jesus Interrupted Biblical scholar Bart Ehrman writes:

“For over a century now, since the landmark publication of Albert Schweitzer’s masterpiece, The Quest of the Historical Jesus, the majority of scholars in Europe and North America have understood Jesus as a Jewish apocalyptic prophet”

“The early Christians, like Jesus before them, and John the Baptist before him, were apocalyptically minded Jews, expecting the imminent end of the age.”

In the Gospel of Mark, Matthew and Luke, Jesus predicts that before many of those he’s talking to die, the kingdom of heaven will have arrived. As he put it in the Gospel of Mark:

“Some of you standing here will not taste death before they see that the Kingdom of God has come in power” (Mark 9:1)

When this prophecy failed to come to fruition, the scholars of prophecy did what they always do: they shifted the goalposts. When we come to the first millennium there’s a surge of Doomsday predictions that crop up. It started with the millennium itself and then it was pushed out 33 years to be a thousand years after the resurrection. There were similar predictions with the second millennium in 2000.

Columbus’s prophecy, along with those of several other prophets, was based on a reading of Biblical history. He believed that the world would end 7000 years after creation which by his reckoning was 1658.

This fascination with the calendar isn’t tethered to Christianity — though it does seem to be tied to Christian cultures. The two major examples in this vein are the supposed end of the Mayan Long Count calendar in December 2012 and the prophesied end of the age of computers with Y2K in 2000.

In summary then, this first category of Doomsday prophecy seems to be a Western Christian tradition. It’s not clear why the Christian culture should be more fascinated with this form of apocalypse than other cultures. Obviously the Christian emphasis on Apocalypse in the New Testament lays a solid groundwork but despite this also being a key element of the Islamic tradition it is almost unheard of in that tradition to try and pin the end of the world on a specific year. This may have something to do with the nature of the calendar since the Western Gregorian calendar is solar while the Islamic calendar is lunar. The entirely solar character of the Gregorian calendar (and the Julian calendar before it) may be significant in general in this regard if we think of the lunar calendar of Islam and the hybrid lunisolar calendars common elsewhere.

This vein of apocalyptic thinking has a separate psychological footprint and aside from Y2K it is much less common in the secular tradition of apocalypse so let’s move on to the more universal theme in humanity’s apocalyptic thinking.

2. The Chaotic Womb of Apocalypse

The more universal apocalyptic tradition has nothing to do with the calendar and is a tradition with a rich history inside and outside of Western history.

In 2015 The Diplomat published an article titled The Apocalypse Psyche: A Look at Chinese Eschatology. Eschatology is a technical theological term which the Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines as:

1: a branch of theology concerned with the final events in the history of the world or of humankind 2: a belief concerning death, the end of the world, or the ultimate destiny of humankind

This article in The Diplomat looks at the political role of eschatological thinking in the history of China:

In China, an apocalypse best highlights the shift in power and the birth of a new form of governance.

The article talks about a Taoist text written in the 5th century AD called The Divine Incantations Scripture (太上洞渊神咒经) which speaks about

“the return of a messianic figure who will take the faithful and destroy the rest of society and create a new society based upon Taoist teachings.”

A few centuries earlier the idea of Apocalypse was used to undermine the Han Dynasty during the Yellow Turban Rebellion of 184–205 AD. At this time many Taoists proclaimed that the inequality of the time — when “the massive peasant classes worked for a pittance and faced heavy taxation” — would end in a period of destruction out of which a new order of society would be reborn.

Moving westward, the Pew Research Centre conducted a poll in 2012 among Muslims across the world from East Asia to Sub-Saharan Africa and Europe. This poll asked participants about their belief in a number of Muslim doctrines. The poll found that 50% or more of respondents in a number of Muslim-majority countries expected the Mahdi (the final redeemer according to Islam) to return during their lifetime. The countries where this belief was highest were Afghanistan where 83% believed this and Iraq where 72% believed this. When we connect the American invasions of these countries in the decade preceding this poll and The Diplomat author’s connection between apocalyptic thinking and social upheaval, the psychology underpinning these numbers becomes less surprising.

Chaos in Western History

The same pattern shows up throughout history.

Jesus’s doomsday work — along with John the Baptist before him and Paul after him — can be seen against the backdrop of the Roman conquest of Israel and of the Western world in general. Israel had become a part of Rome just sixty years before Jesus’s birth and in that time there had been two civil wars and a transformation of Rome from a republic into an empire. Three decades after Jesus’s death there began the Jewish-Roman wars during which the Second Temple was destroyed.

In England’s 17th century civil wars there were fervent apocalyptic expectations among radical parliamentary sects that were shared by the likes of Oliver Cromwell and John Milton.

In the late 18th century the French Revolution triggered an even greater deluge of apocalyptic feeling. There was a surge of preachers who interpreted events in France in terms of Biblical prophecies. In 1791 Thomas Holcroft wrote:

“Hey for the New Jerusalem! The millennium!”

The Romantic poets of England all got caught up in this fury. During the French Revolution Coleridge summarised his expectation as:

“The French Revolution. Millennium. Universal Redemption. Conclusion.”

Blake speaks of a revolutionary “son of fire” moving from America to France and heralding a new age:

“Empire is no more! and now the lion & wolf shall cease”

Meanwhile Wordsworth in the concluded 1793’s Descriptive Sketches with the enthusiastic prophecy that the French Revolution was the beginning of the fulfilment of the Book of Revelation.

The Chaotic 19th Century

Of course the language of apocalypse at this time is still very recognisably Christian and couched in the Christian worldview. But as we enter the middle of the 19th century and the death of God begins in Germany with works like The Life of Jesus by David Strauss uncovering the historical Jesus and then on the other hand Darwin’s work on evolution being published things begin to take a turn for the atheistic.

The 19th century was a time of dramatic social upheaval. This was the time when Europe as a whole was moving from the age of Feudalism into the age of industrialised modernity. Capitalism was beginning its takeover of the world.

This liminal period brought with it idealistic dreams and terrifying realities. This was the peak of Utopian Socialist thinking and it was a time of revolution. In the 1820s there were revolutions in Spain, Portugal, Greece and Russia. In the 1830s there were revolutions in Belgium, France, Italy, Poland, Portugal and Switzerland. The European pressure cooker exploded in 1848. This momentous year saw a wave of revolutions spread across Europe — the greatest wave of revolutions the continent has ever seen. It began in Sicily then France and from there it spread across the entire continent with the exceptions of Russia, Spain, and the Scandinavian countries.

It is against the backdrop of these decades of revolution that Marxism was born. At the core of Marx’s thinking was the prophecy of the uprising of the proletariat. Marx was working off a Hegelian vision of history in which history’s progression is seen much like the butterfly’s evolution from the caterpillar. When Marx first moved to London in 1849 he believed the next phase of historical evolution was imminent — that widespread Proletarian revolution across the continent was imminent. He and Engels made prediction after prediction for this revolution until ultimately Marx had to accept that it might not come immediately.

Nevertheless, his whole career he continued to believe in the inevitable toppling of Capitalism by Communism. It was as inevitable as the summer following the spring. This prophecy was at the heart of the Marxist spirit and drove the revolutionary movement into the 20th century.

The Cold War with its climate of nuclear apocalypse had a similar backdrop with the two wars to end all wars.

The Chaotic 21st Century

And with the 21st century the upheaval of life continues at a social level. The economic and social disruption of Neoliberalism and digital life has led to a disruption of all stability. As rapid transformation has taken over, the apocalyptic rhetoric has increased in shrillness once again.

The appropriately named Millennials and the Generation Z that follow them are growing up in a world of incredible abundance but find that in many ways they have missed the party. The cost of entry to the party has left millions saddled with unmanageable debt. This combined with the skyrocketing cost of property and with university education becoming a (very expensive) commonplace, generations of discontented and disenfranchised youth without the crippling demands to feed themselves have become conscious of a raw deal.

The end of the world in this scenario gives urgency and archetypal charge to the idea of a climate crisis.

Inheriting a world with high entry costs, the environment plundered and a ticking timer attached has created a breeding ground for discontent with the system. As the Bourbons learned with the French Revolution, when the wealth disparity reaches extremes and the lower classes feel cheated, they feel they have nothing to lose by toppling the system. This is the feeling of many Millennials and Gen Z today.

This might be one explanation for why the climate crisis has become such a politically charged issue. It is the end of the world scenario that gives an eschatological urgency to the social problems felt by the Millennials. It is a bludgeon of rebuttal that can be wielded by a disaffected class. In the past, such social unrest has led to the formation of Islam and the wars that surrounded it; the creation of Christianity; and the terrors of the French Revolution.

The end of the world in this scenario gives urgency and archetypal charge to the idea of a climate crisis.

Examining the psychological fervour around the Climate Crisis we can see one of the universal patterns of human history: when the world changes the archetypal unconscious of humanity vomits into the everyday world. As with all archetypal eruptions, it is bipolar. As the social upheaval at the emergence of Islam and Christianity brought a divine revelation of hope it also brought with it a terrifying end to history. The same goes for the Taoist myths in Ancient China.

We find this same pattern recurring throughout the secular age of modernity. In the 19th century there were dreams of a Utopian world where the Kingdom of Heaven would finally find its home on Earth. But with these visions of greatness there emerged a vision of a holy war between the classes that would be needed to bring about this transition. In the 21st century political instability has brought visions of horror with Climate Change but also dreams of a Socialist future in the leftist camps and the vision of techno-utopia that is the Singularity in the nerd camp.

There are still many questions to be asked and answered as to the nature of this psychological need for apocalypse. We might ask whether such attitudes are the laying bare of human biases when their model of the world breaks down. We might wonder whether there is an evolutionary component and whether such an archetypal splitting of utopian and dystopian thinking is adaptive to creating new order out of the disintegration of the social chaos. I suspect that this psychology can be meaningfully illuminated by the anthropological idea of Liminality which we will be covering in a future instalment.

For now I hope this article has provoked some thought and added a new way of looking at events in the world and offers the possibility of seeing the psychological shadows of the ages separate from the topical content of the day. Once again none of this psychological dissection is meant to detract from the reality of the crises that face us. It is merely a way of sobering us up from archetypal intoxication so that we are more able to communicate and cooperate rather than playing out archetypal dramas. This seems to be something of a theme on the channel and it brings to mind the instalment on the Jordan Peterson and Olivia Wilde debacle.

One Comment

-

Your work is a vital resource in today’s fast-paced world.

Your work is a vital resource in today’s fast-paced world.