The history of philosophy is a tapestry composed of colourful characters. If there was a distinction for the most eccentric and colourful among this peculiar bunch, there is no doubt that Empedocles of Acragas would be in the running.

It is a rare philosopher who claims to be a god; it’s an even rarer one that raises people from the dead and cures a whole town of plague all the while strutting about dressed like a king. If Empedocles was anything, he was a rare breed.

While he is known today solely as a Presocratic philosopher, he was famous in his own time not just for philosophy but for medicine, theology, magic and politics. It seems more accurate to characterise him as a shaman who practised philosophy than as a philosopher who dabbled in shamanism.

In this article, we will talk a little about this colourful Sicilian and explore the mechanistic world philosophy that he developed and how this philosophy led him to conceive a primitive theory of evolution.

The Wise Man of Sicily

Empedocles was born in the early 5th century BCE in the polis of Acragas (now known as Agrigento) on the bottom of the Italian island Sicily. He was from a wealthy aristocratic background and his grandfather — also called Empedocles — was victorious in the horse racing at the Olympic Games in 496 BCE.

He was famous for many things, among them his generosity and his regal style of dress — he used to wear a purple robe, a golden girdle bronze sandals and a Delphic laurel wreath.

In his sixty years he accrued quite a list of accolades:

- Aristotle credited him with the invention of Rhetoric — one of the most important arts in the ancient world

- In politics, he was a champion of equality prosecuting state officials, helping to bring down an oligarchy and helping to institute a democracy in his home polis.

- In medicine, he was hailed as the founder of the Sicilian school of medicine (and as the great Roman physician Galen believed — the inventor of the science of medicine itself)

- He apparently raised a woman from the dead after her death 30 days previously

- He cured an entire town of plague (though apparently that was just his restoration of the freshwater supply)

- He was a fantastic poet adored and imitated by the greatest poet-philosopher Lucretius

- And last but not least, he was worshipped as a god in his own lifetime.

But the most famous incident from the life of Empedocles is, without a doubt, his death. There are many stories about his demise — the most famous being that he jumped into the fires of the Sicilian volcano Mt. Etna to prove that he was a god.

In some accounts, he flew up to heaven; in others, his ruse was foiled by one of his bronze slippers flying back out. This death was eternalised by the poet Matthew Arnold in the lines:

Great Empedocles, that ardent soul,

Leapt into Etna, and was roasted whole.

In all likelihood, of course, this isn’t true. However, it still stands as one among so many colourful anecdotes in the life of a man who has been regarded as everything from a materialist physicist, a shamanic magician, a mystical theologian, a healer, a democratic politician, a living god and a fraud.

The Cosmology of Empedocles

Aside from this colourful biography, Empedocles was quite the philosopher. He seems to have written two books On Nature and Purifications; that being said, there is a growing consensus among scholars that there may have been just one book or that the two may at least have been closer related than previously suspected.

On Nature is his work of cosmogony and science while Purifications contains his more mystical Pythagorean strain of thinking — more concerned with healing and magic than traditional philosophy. It’s there that we find his gnostic sort of beliefs in reincarnation as expiation for the sin of eating meat as gods and hence his ardent vegetarianism.

But what concerns us here is his work On Nature. The backdrop of this work is — like the work of Anaxagoras — to do with the great challenge to philosophy created by Parmenides’s philosophy.

In a beautiful work of poetry, Parmenides laid out a philosophical argument that seemed to make an airtight argument that everything is one and that everything is unchanging. The essence of this argument is something like: how could something have come out of nothing or go into nothing; this is impossible. But, of course, the trouble with this — as Heraclitus highlighted — was that everything is changing all the time.

The challenge for the philosophers following Parmenides was to reconcile this unchanging nature of reality with the apparent ever-changingness of nature.

The “Roots” of the Matter

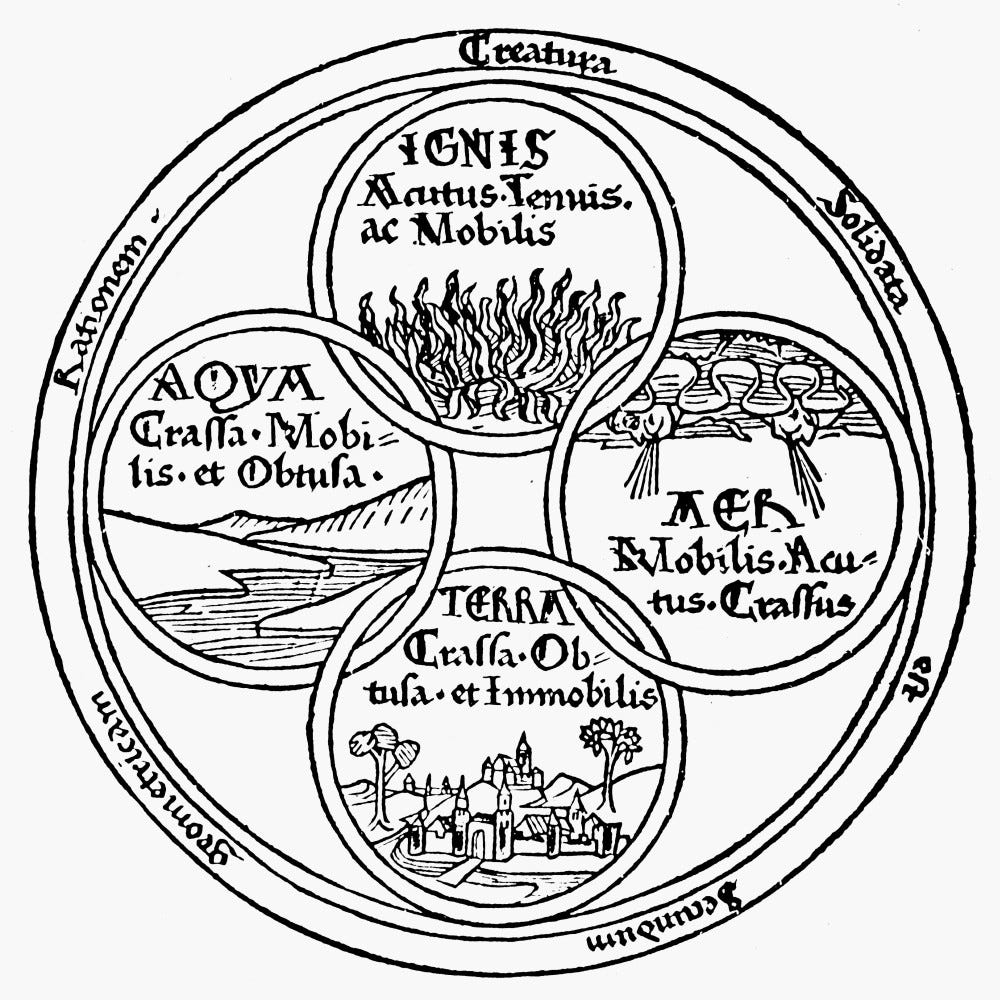

The response of Empedocles is similar to that of Anaxagoras but instead of “seeds,” which could be anything from heat or soft to dark or heavy, Empedocles calls his basic atoms “roots” and they come in four varieties — earth, air, water and fire.

The entirety of the universe is made up of these four basic elements. These individual elements of water, air, earth and fire are unchanging, eternal and innumerable; this is how Empedocles gets around Parmenides’ argument — he makes his elements eternal and unchanging but he makes them innumerable.

These elements move and concentrate in different amounts and this movement and concentration is what gives us the reality we see around us. Everything is a mix of these four elements.

A Tale of Two Forces

As well as these four elements, Empedocles also postulates two forces. Without these forces, the elements would be in an eternal stasis. It is these forces that set the world of becoming and change in motion.

These two forces are called Love and Strife.

Love is the force of attraction; it brings the elements together in harmony. Strife on the other hand separates the elements apart causing them to seek their own kind.

The struggle between these two forces for dominance of the universe creates a cyclical pattern with four phases.

1. Love’s Hegemony:

At one end of the cycle Love rules the roost and Strife is excluded. Everything is all one spherical perfect undistinguished oneness and while they are not fused into one mass they are indistinguishable from the others. In this state no matter or life can exist because all the elements are so melded into one. This is how Empedocles describes it:

There neither the swift limbs of the sun are discerned, nor the shaggy force of earth nor the sea.

Thus by the dense concealment of Harmonia is held fast a rounded sphere, exulting in its joyous solitude. (B27)

2. The Weakening of Love:

As this most divine stage of Love’s hegemony begins to weaken Strife begins to grow in power and starts to separate the elements out until there is enough separation that matter begins to form and the world and life come into existence.

3. Strife’s Hegemony:

As this process continues Strife reaches a state of total domination and again we get an acosmic state that Empedocles called “the whirl” where matter and life cease to be because all the elements are separated out into their own kinds — water with water, air with air and so on.

4. The Weakening of Strife:

And then once again the dominance of Strife begins to wane and Love begins to grow in power and we have once again the emergence of matter the world and life. And eventually this brings us back to the start of the cycle where Love rules the roost.

The great wheel of time then has four phases — two extremes where one force dominates and in between these extremes a time where neither completely rules. These in-betweens are the cosmic eras where life is possible. This is what Empedocles is referring to when he says “double is the birth of mortal things, double their death.”

Of course there is a difference between these two phases of life. One is leaving Strife and heading towards Love and the other is heading the opposite way. According to Empedocles, our cosmos exists in the fall from Love towards Strife. He thinks of our present world as a:

“Joyless place, where bloodshed, anger, and tribes of other spirits of death and squalid diseases, rotting, and works of dissolution wander in darkness through the meadow of disaster.”

In the moral decline of our world, he sees humanity as having fallen from a golden age and hurtling towards Strife; this dovetails with his theological views on the fall of man.

On the Origin of Species

It is also in these in-between states of life that the Sicilian’s philosopher’s bizarre theory of evolution takes place.

In the early phases of Love and Strife we don’t immediately get the organisms as we know them. At first we get certain random configurations of different body parts. And in these early stages of life we get all sorts of bizarre creations:

Wobbly-footed with countless hands. (B60)

(Plutarch, Against Colotes 1123B)Many grew with faces and chests on both sides, man-faced ox-progeny, and some to the contrary rose up as ox-headed things with the form of men, compounded partly from men and partly from women, fitted with shadowy parts. (B61)

(Aelian, The Nature of Animals 16.29)

But as things progress things begin to fall into place and our own world of order begins to emerge:

But when divinity was mixed to a greater extent with divinity, these things began to fall together, however they chanced to meet, and many others in addition arose continuously. (B59)

(Simplicius, Commentary on Aristotle’s On the Heavens 587.20, 23)

It’s not quite Darwin’s On the Origin of Species but it’s pretty spectacular to see this early emergence of an evolutionary theory considering it took a further two millennia before Darwin showed up with his slightly more worked out version.

Of course, rather than starting with an organism that evolves these bits as in Darwinian evolution, in Empedocles’s evolution you start with the bits and they evolve into organisms. It’s a bizarre hypothesis but one can’t help but admire the colourfulness and originality and given the rest of his philosophy and the shape of his life, we couldn’t expect more than this from the shaman of Sicily.

The history of philosophy is a tapestry composed of colourful characters. If there was a distinction for the most eccentric and colourful among this peculiar bunch, there is no doubt that Empedocles of Acragas would be in the running.

It is a rare philosopher who claims to be a god; it’s an even rarer one that raises people from the dead and cures a whole town of plague all the while strutting about dressed like a king. If Empedocles was anything, he was a rare breed.

While he is known today solely as a Presocratic philosopher, he was famous in his own time not just for philosophy but for medicine, theology, magic and politics. It seems more accurate to characterise him as a shaman who practised philosophy than as a philosopher who dabbled in shamanism.

In this article, we will talk a little about this colourful Sicilian and explore the mechanistic world philosophy that he developed and how this philosophy led him to conceive a primitive theory of evolution.

The Wise Man of Sicily

Empedocles was born in the early 5th century BCE in the polis of Acragas (now known as Agrigento) on the bottom of the Italian island Sicily. He was from a wealthy aristocratic background and his grandfather — also called Empedocles — was victorious in the horse racing at the Olympic Games in 496 BCE.

He was famous for many things, among them his generosity and his regal style of dress — he used to wear a purple robe, a golden girdle bronze sandals and a Delphic laurel wreath.

In his sixty years he accrued quite a list of accolades:

- Aristotle credited him with the invention of Rhetoric — one of the most important arts in the ancient world

- In politics, he was a champion of equality prosecuting state officials, helping to bring down an oligarchy and helping to institute a democracy in his home polis.

- In medicine, he was hailed as the founder of the Sicilian school of medicine (and as the great Roman physician Galen believed — the inventor of the science of medicine itself)

- He apparently raised a woman from the dead after her death 30 days previously

- He cured an entire town of plague (though apparently that was just his restoration of the freshwater supply)

- He was a fantastic poet adored and imitated by the greatest poet-philosopher Lucretius

- And last but not least, he was worshipped as a god in his own lifetime.

But the most famous incident from the life of Empedocles is, without a doubt, his death. There are many stories about his demise — the most famous being that he jumped into the fires of the Sicilian volcano Mt. Etna to prove that he was a god.

In some accounts, he flew up to heaven; in others, his ruse was foiled by one of his bronze slippers flying back out. This death was eternalised by the poet Matthew Arnold in the lines:

Great Empedocles, that ardent soul,

Leapt into Etna, and was roasted whole.

In all likelihood, of course, this isn’t true. However, it still stands as one among so many colourful anecdotes in the life of a man who has been regarded as everything from a materialist physicist, a shamanic magician, a mystical theologian, a healer, a democratic politician, a living god and a fraud.

The Cosmology of Empedocles

Aside from this colourful biography, Empedocles was quite the philosopher. He seems to have written two books On Nature and Purifications; that being said, there is a growing consensus among scholars that there may have been just one book or that the two may at least have been closer related than previously suspected.

On Nature is his work of cosmogony and science while Purifications contains his more mystical Pythagorean strain of thinking — more concerned with healing and magic than traditional philosophy. It’s there that we find his gnostic sort of beliefs in reincarnation as expiation for the sin of eating meat as gods and hence his ardent vegetarianism.

But what concerns us here is his work On Nature. The backdrop of this work is — like the work of Anaxagoras — to do with the great challenge to philosophy created by Parmenides’s philosophy.

In a beautiful work of poetry, Parmenides laid out a philosophical argument that seemed to make an airtight argument that everything is one and that everything is unchanging. The essence of this argument is something like: how could something have come out of nothing or go into nothing; this is impossible. But, of course, the trouble with this — as Heraclitus highlighted — was that everything is changing all the time.

The challenge for the philosophers following Parmenides was to reconcile this unchanging nature of reality with the apparent ever-changingness of nature.

The “Roots” of the Matter

The response of Empedocles is similar to that of Anaxagoras but instead of “seeds,” which could be anything from heat or soft to dark or heavy, Empedocles calls his basic atoms “roots” and they come in four varieties — earth, air, water and fire.

The entirety of the universe is made up of these four basic elements. These individual elements of water, air, earth and fire are unchanging, eternal and innumerable; this is how Empedocles gets around Parmenides’ argument — he makes his elements eternal and unchanging but he makes them innumerable.

These elements move and concentrate in different amounts and this movement and concentration is what gives us the reality we see around us. Everything is a mix of these four elements.

A Tale of Two Forces

As well as these four elements, Empedocles also postulates two forces. Without these forces, the elements would be in an eternal stasis. It is these forces that set the world of becoming and change in motion.

These two forces are called Love and Strife.

Love is the force of attraction; it brings the elements together in harmony. Strife on the other hand separates the elements apart causing them to seek their own kind.

The struggle between these two forces for dominance of the universe creates a cyclical pattern with four phases.

1. Love’s Hegemony:

At one end of the cycle Love rules the roost and Strife is excluded. Everything is all one spherical perfect undistinguished oneness and while they are not fused into one mass they are indistinguishable from the others. In this state no matter or life can exist because all the elements are so melded into one. This is how Empedocles describes it:

There neither the swift limbs of the sun are discerned, nor the shaggy force of earth nor the sea.

Thus by the dense concealment of Harmonia is held fast a rounded sphere, exulting in its joyous solitude. (B27)

2. The Weakening of Love:

As this most divine stage of Love’s hegemony begins to weaken Strife begins to grow in power and starts to separate the elements out until there is enough separation that matter begins to form and the world and life come into existence.

3. Strife’s Hegemony:

As this process continues Strife reaches a state of total domination and again we get an acosmic state that Empedocles called “the whirl” where matter and life cease to be because all the elements are separated out into their own kinds — water with water, air with air and so on.

4. The Weakening of Strife:

And then once again the dominance of Strife begins to wane and Love begins to grow in power and we have once again the emergence of matter the world and life. And eventually this brings us back to the start of the cycle where Love rules the roost.

The great wheel of time then has four phases — two extremes where one force dominates and in between these extremes a time where neither completely rules. These in-betweens are the cosmic eras where life is possible. This is what Empedocles is referring to when he says “double is the birth of mortal things, double their death.”

Of course there is a difference between these two phases of life. One is leaving Strife and heading towards Love and the other is heading the opposite way. According to Empedocles, our cosmos exists in the fall from Love towards Strife. He thinks of our present world as a:

“Joyless place, where bloodshed, anger, and tribes of other spirits of death and squalid diseases, rotting, and works of dissolution wander in darkness through the meadow of disaster.”

In the moral decline of our world, he sees humanity as having fallen from a golden age and hurtling towards Strife; this dovetails with his theological views on the fall of man.

On the Origin of Species

It is also in these in-between states of life that the Sicilian’s philosopher’s bizarre theory of evolution takes place.

In the early phases of Love and Strife we don’t immediately get the organisms as we know them. At first we get certain random configurations of different body parts. And in these early stages of life we get all sorts of bizarre creations:

Wobbly-footed with countless hands. (B60)

(Plutarch, Against Colotes 1123B)Many grew with faces and chests on both sides, man-faced ox-progeny, and some to the contrary rose up as ox-headed things with the form of men, compounded partly from men and partly from women, fitted with shadowy parts. (B61)

(Aelian, The Nature of Animals 16.29)

But as things progress things begin to fall into place and our own world of order begins to emerge:

But when divinity was mixed to a greater extent with divinity, these things began to fall together, however they chanced to meet, and many others in addition arose continuously. (B59)

(Simplicius, Commentary on Aristotle’s On the Heavens 587.20, 23)

It’s not quite Darwin’s On the Origin of Species but it’s pretty spectacular to see this early emergence of an evolutionary theory considering it took a further two millennia before Darwin showed up with his slightly more worked out version.

Of course, rather than starting with an organism that evolves these bits as in Darwinian evolution, in Empedocles’s evolution you start with the bits and they evolve into organisms. It’s a bizarre hypothesis but one can’t help but admire the colourfulness and originality and given the rest of his philosophy and the shape of his life, we couldn’t expect more than this from the shaman of Sicily.

Leave A Comment

The history of philosophy is a tapestry composed of colourful characters. If there was a distinction for the most eccentric and colourful among this peculiar bunch, there is no doubt that Empedocles of Acragas would be in the running.

It is a rare philosopher who claims to be a god; it’s an even rarer one that raises people from the dead and cures a whole town of plague all the while strutting about dressed like a king. If Empedocles was anything, he was a rare breed.

While he is known today solely as a Presocratic philosopher, he was famous in his own time not just for philosophy but for medicine, theology, magic and politics. It seems more accurate to characterise him as a shaman who practised philosophy than as a philosopher who dabbled in shamanism.

In this article, we will talk a little about this colourful Sicilian and explore the mechanistic world philosophy that he developed and how this philosophy led him to conceive a primitive theory of evolution.

The Wise Man of Sicily

Empedocles was born in the early 5th century BCE in the polis of Acragas (now known as Agrigento) on the bottom of the Italian island Sicily. He was from a wealthy aristocratic background and his grandfather — also called Empedocles — was victorious in the horse racing at the Olympic Games in 496 BCE.

He was famous for many things, among them his generosity and his regal style of dress — he used to wear a purple robe, a golden girdle bronze sandals and a Delphic laurel wreath.

In his sixty years he accrued quite a list of accolades:

- Aristotle credited him with the invention of Rhetoric — one of the most important arts in the ancient world

- In politics, he was a champion of equality prosecuting state officials, helping to bring down an oligarchy and helping to institute a democracy in his home polis.

- In medicine, he was hailed as the founder of the Sicilian school of medicine (and as the great Roman physician Galen believed — the inventor of the science of medicine itself)

- He apparently raised a woman from the dead after her death 30 days previously

- He cured an entire town of plague (though apparently that was just his restoration of the freshwater supply)

- He was a fantastic poet adored and imitated by the greatest poet-philosopher Lucretius

- And last but not least, he was worshipped as a god in his own lifetime.

But the most famous incident from the life of Empedocles is, without a doubt, his death. There are many stories about his demise — the most famous being that he jumped into the fires of the Sicilian volcano Mt. Etna to prove that he was a god.

In some accounts, he flew up to heaven; in others, his ruse was foiled by one of his bronze slippers flying back out. This death was eternalised by the poet Matthew Arnold in the lines:

Great Empedocles, that ardent soul,

Leapt into Etna, and was roasted whole.

In all likelihood, of course, this isn’t true. However, it still stands as one among so many colourful anecdotes in the life of a man who has been regarded as everything from a materialist physicist, a shamanic magician, a mystical theologian, a healer, a democratic politician, a living god and a fraud.

The Cosmology of Empedocles

Aside from this colourful biography, Empedocles was quite the philosopher. He seems to have written two books On Nature and Purifications; that being said, there is a growing consensus among scholars that there may have been just one book or that the two may at least have been closer related than previously suspected.

On Nature is his work of cosmogony and science while Purifications contains his more mystical Pythagorean strain of thinking — more concerned with healing and magic than traditional philosophy. It’s there that we find his gnostic sort of beliefs in reincarnation as expiation for the sin of eating meat as gods and hence his ardent vegetarianism.

But what concerns us here is his work On Nature. The backdrop of this work is — like the work of Anaxagoras — to do with the great challenge to philosophy created by Parmenides’s philosophy.

In a beautiful work of poetry, Parmenides laid out a philosophical argument that seemed to make an airtight argument that everything is one and that everything is unchanging. The essence of this argument is something like: how could something have come out of nothing or go into nothing; this is impossible. But, of course, the trouble with this — as Heraclitus highlighted — was that everything is changing all the time.

The challenge for the philosophers following Parmenides was to reconcile this unchanging nature of reality with the apparent ever-changingness of nature.

The “Roots” of the Matter

The response of Empedocles is similar to that of Anaxagoras but instead of “seeds,” which could be anything from heat or soft to dark or heavy, Empedocles calls his basic atoms “roots” and they come in four varieties — earth, air, water and fire.

The entirety of the universe is made up of these four basic elements. These individual elements of water, air, earth and fire are unchanging, eternal and innumerable; this is how Empedocles gets around Parmenides’ argument — he makes his elements eternal and unchanging but he makes them innumerable.

These elements move and concentrate in different amounts and this movement and concentration is what gives us the reality we see around us. Everything is a mix of these four elements.

A Tale of Two Forces

As well as these four elements, Empedocles also postulates two forces. Without these forces, the elements would be in an eternal stasis. It is these forces that set the world of becoming and change in motion.

These two forces are called Love and Strife.

Love is the force of attraction; it brings the elements together in harmony. Strife on the other hand separates the elements apart causing them to seek their own kind.

The struggle between these two forces for dominance of the universe creates a cyclical pattern with four phases.

1. Love’s Hegemony:

At one end of the cycle Love rules the roost and Strife is excluded. Everything is all one spherical perfect undistinguished oneness and while they are not fused into one mass they are indistinguishable from the others. In this state no matter or life can exist because all the elements are so melded into one. This is how Empedocles describes it:

There neither the swift limbs of the sun are discerned, nor the shaggy force of earth nor the sea.

Thus by the dense concealment of Harmonia is held fast a rounded sphere, exulting in its joyous solitude. (B27)

2. The Weakening of Love:

As this most divine stage of Love’s hegemony begins to weaken Strife begins to grow in power and starts to separate the elements out until there is enough separation that matter begins to form and the world and life come into existence.

3. Strife’s Hegemony:

As this process continues Strife reaches a state of total domination and again we get an acosmic state that Empedocles called “the whirl” where matter and life cease to be because all the elements are separated out into their own kinds — water with water, air with air and so on.

4. The Weakening of Strife:

And then once again the dominance of Strife begins to wane and Love begins to grow in power and we have once again the emergence of matter the world and life. And eventually this brings us back to the start of the cycle where Love rules the roost.

The great wheel of time then has four phases — two extremes where one force dominates and in between these extremes a time where neither completely rules. These in-betweens are the cosmic eras where life is possible. This is what Empedocles is referring to when he says “double is the birth of mortal things, double their death.”

Of course there is a difference between these two phases of life. One is leaving Strife and heading towards Love and the other is heading the opposite way. According to Empedocles, our cosmos exists in the fall from Love towards Strife. He thinks of our present world as a:

“Joyless place, where bloodshed, anger, and tribes of other spirits of death and squalid diseases, rotting, and works of dissolution wander in darkness through the meadow of disaster.”

In the moral decline of our world, he sees humanity as having fallen from a golden age and hurtling towards Strife; this dovetails with his theological views on the fall of man.

On the Origin of Species

It is also in these in-between states of life that the Sicilian’s philosopher’s bizarre theory of evolution takes place.

In the early phases of Love and Strife we don’t immediately get the organisms as we know them. At first we get certain random configurations of different body parts. And in these early stages of life we get all sorts of bizarre creations:

Wobbly-footed with countless hands. (B60)

(Plutarch, Against Colotes 1123B)Many grew with faces and chests on both sides, man-faced ox-progeny, and some to the contrary rose up as ox-headed things with the form of men, compounded partly from men and partly from women, fitted with shadowy parts. (B61)

(Aelian, The Nature of Animals 16.29)

But as things progress things begin to fall into place and our own world of order begins to emerge:

But when divinity was mixed to a greater extent with divinity, these things began to fall together, however they chanced to meet, and many others in addition arose continuously. (B59)

(Simplicius, Commentary on Aristotle’s On the Heavens 587.20, 23)

It’s not quite Darwin’s On the Origin of Species but it’s pretty spectacular to see this early emergence of an evolutionary theory considering it took a further two millennia before Darwin showed up with his slightly more worked out version.

Of course, rather than starting with an organism that evolves these bits as in Darwinian evolution, in Empedocles’s evolution you start with the bits and they evolve into organisms. It’s a bizarre hypothesis but one can’t help but admire the colourfulness and originality and given the rest of his philosophy and the shape of his life, we couldn’t expect more than this from the shaman of Sicily.