Neurosis addles the brains of every philosopher because he is at odds with himself. His philosophy is then nothing but a systemized struggle with his own uncertainty. — Letter to Arnold Kiinzli, 28 February 1943

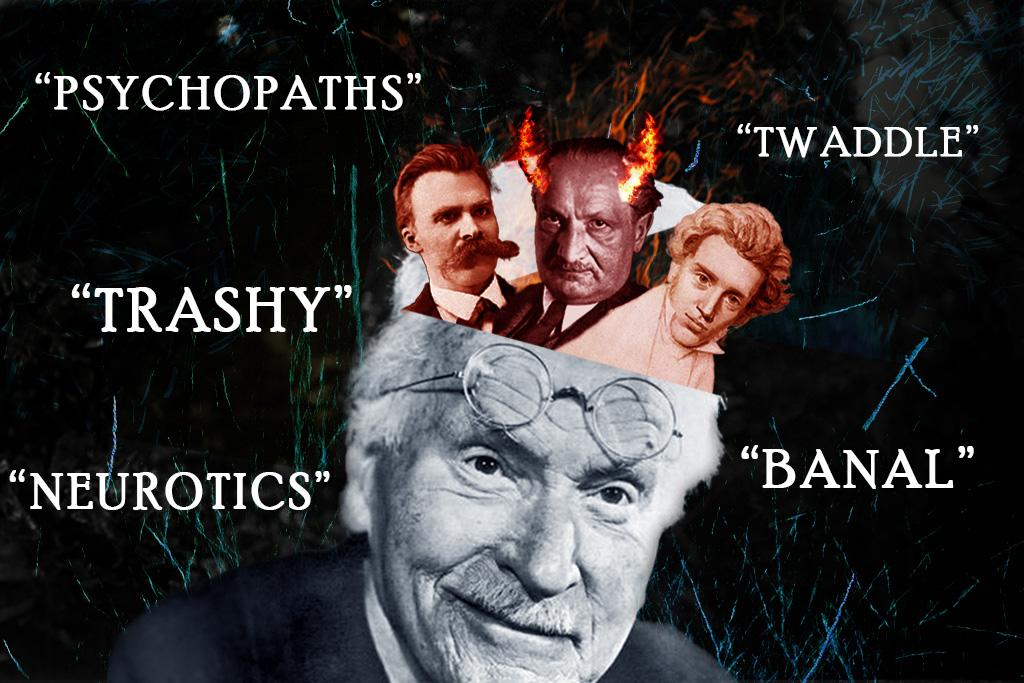

I came across this letter recently where Jung wrote some pretty salty things about the Existentialist philosophers Kierkegaard and Heidegger. My interest piqued I decided to search through Jung’s Collected Works and the collections of his letters to see what else the Swiss psychologist had to say about philosophers. What emerged was a fascinating picture of a man who really did not respect the Existentialist philosophers and didn’t have many kind words for philosophers in general. The opening quote is pretty typical in theme and tone of what he has to say.

The first surprising thing is that in the thousands of pages of this Collected Works and letters there is little mention of philosophers at all. Jung says a few nice things about Socrates, mentions Plato in passing a few times and the same with Kant. But despite his comment in one letter that “Philosophically I am old-fashioned enough not to have got beyond Kant” Jung has much less to say about the philosophers before Kant than he does about those after. And none of these things are particularly pleasant. He manages to hit all the major philosophers after Kant in this drive-by rampage: Hegel, Schopenhauer, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche and most of all Heidegger.

With the exception of Nietzsche and a little bit of Kierkegaard, Jung doesn’t seem to have read anything by these philosophers. Nietzsche stands out for him as a mixed bag: the German philosopher was both a troubled mind and a very inspiring Muse whose influence can be seen throughout Jung’s work.

This strained relationship between Jung and philosophy is all the more peculiar since he used to brag to Freud that he was adept at philosophy and Freud wasn’t. In this instalment we’re going to explore this unusual relationship between Jung and philosophy. In the first half of the article we’ll look at the various slanders Jung had for these philosophers. Then in the second half of the article I want to try and get under the mask. We are going to dig down on this comment to Freud and follow up on the cue of legendary Nietzsche translator Walter Kaufmann who saw the workings of Jung’s Shadow in these “wildly emotional” comments on philosophers. I will argue that Jung’s disdain for these philosophers he had little to no experience with speaks to the tension in his psyche between what he calls Personality №1 and Personality №2. This theme as we’ll see runs throughout his life and his work with the philosopher carrying the archetypal image of Jung’s unlived life.

Beyond their proper bounds

Jung’s attacks on the philosophers fall into two categories. Firstly he accuses the philosophers of going beyond their proper bounds. And secondly he accuses them, as in the opening quote, of being mentally ill.

In the first case the philosophers grind Jung’s gears by going beyond their proper bounds and being unscientific. In this vein we see that Jung’s critique doesn’t just apply to Heidegger and Kierkegaard but also to Hegel and German philosophy in general:

Moreover this whole intellectual perversion is a German national institution.

In one letter he says that he considers all speculations that go beyond our current capacities as being “a pretext for covering up one’s own infertility”. And in a later letter he speaks about the need for philosophical criticism to be grounded in factual knowledge if it’s not to “remain hanging in mid-air and thus to be condemned to sterility”.

In another letter he says that the Heideggerian school of philosophers “merely play verbal tricks”. In this letter to Josef Meinertz — the author of a book on psychotherapy and philosophy — he dismisses the way such philosophers deal with death:

An especially delectable morsel is the way the philosophers juggle with death. I can’t wait for the dissertation “How is Death Possible?” or “The Philosophical Foundations of Death.” Excuse these heretical fits of mine; they spring from practical experience, where the impotence of philosophical language is revealed at its starkest.

From what he’s gleaned from Meinertz’s work he says:

What Heidegger, Klages, and Jaspers have to say in this respect has never affected me very deeply, for one notices the same thing in all writers who have never had to wrestle with the practical problems of psychotherapy. They all have an astonishing facility with words, which they endow with an almost magical efficacy. If Klages had had to treat a single case of neurosis he would never have brought off that thick tome on the obnoxious spirit. Similarly, Heidegger would have lost all desire to juggle with words.

Jung is always aspiring to the ideal of science and philosophical criticism comes up short for him insofar as it fails to “meet all the requirements of the scientific attitude”.

Where philosophy fails to meet these requirements it becomes a mere reflection of the philosopher’s “unconscious subjective prejudices”. Given the private medium of letter-writing it’s fun to see Jung dabbling in a bit of salty language. In one letter he says that:

There is no thinking qua thinking, at times it is a pisspot of unconscious devils

And in another great line from one of the letters he writes regarding Kierkegaard’s concept of Anxiety:

The philosopher starts from the anxiety that possesses him and then, through reflection, turns his subjective state of being possessed into a perception of anxiety. Question: is it an object worthy of anxiety, or a poltroonery [a cowardly act] of the ego, shitting its pants?

Jung’s point here echoes Nietzsche’s line on the prejudices of philosophers from Beyond Good and Evil where he writes that:

“most of the conscious thinking of a philosopher is secretly guided and forced into certain channels by his instincts”

Of all the philosophers Jung holds a special place in his heart for Heidegger. Presumably at the time that most of these letters were being written in the 1930s Heidegger was coming into the fullness of his popularity. Jung writes that Heidegger “bristles” with the aforementioned “unconscious subjective prejudices” and he tries:

“in vain to hide behind a blown-up language”.

He describes Heidegger’s writing as “twaddle” and when a colleague of his read out some Heidegger at a conference he found it was “positively comic”:

The substance of what he read out was unutterably trashy and banal, and Brinkmann could just as well have done it to make Heidegger ridiculous

In summation then this is the first part of Jung’s critique of philosophers; he says that philosophy is a constant overstepping of its bounds. We could maybe call this a Kantian hygienics. He wants to keep to a scientific project of what can be known. He writes that:

Philosophy has still to learn that it is made by human beings and depends to an alarming degree on their psychic constitution

And this psychic constitution is on Jung’s account far too often and far too deeply neurotic.

A bunch of neurotics

For Jung, the philosophies of Nietzsche, Kierkegaard and Heidegger are all confessions of their own neuroticism. As we saw in the opening quote Jung puts this confessional element much more shrilly than Nietzsche:

Neurosis addles the brains of every philosopher because he is at odds with himself. His philosophy is then nothing but a systemized struggle with his own uncertainty

He launches a few broadsides at philosophers in these letters. Hegel “is fit to burst with presumption and vanity”, Nietzsche “drips with outraged sexuality”. Kierkegaard he repeatedly calls a grizzler [a term which I had to look up; grizzling it turns out means “the action, typically by a child, of crying fretfully” or as the Cambridge dictionary puts it “to cry continuously but not very loudly, or to complain all the time”; so Jung is basically calling Kierkegaard a cry-baby]. Of the Danish philosopher’s brilliance Jung writes:

“Kierkegaard was a stimulating and pioneering force precisely because of his neurosis”

True to form he holds his harshest sentiments for Heidegger going so far as to say:

Heidegger’s modus philosophandi is neurotic through and through and is ultimately rooted in his psychic crankiness. His kindred spirits, close or distant, are sitting in lunatic asylums, some as patients and some as psychiatrists on a philosophical rampage.

This neurosis is key in the content of their philosophies. Their uncertainty with themselves — the sense that they stand on ice of uncertain thickness and which may crack at any moment drowning them in the cold waters of their depths — is key to their philosophies. The doubt that such neurosis cultivates in the neurotic infects their vision of their fellow humans and of the world. As Jung puts it:

Neurosis is a justified doubt in oneself and continually poses the ultimate question of trust in man and in God. Doubt is creative if it is answered by deeds, and so is neurosis if it exonerates itself as having been a phase — a crisis which is pathological only when chronic. Neurosis is a protracted crisis degenerated into a habit, the daily catastrophe ready for use.

This neuroticism is perhaps most obvious in Kierkegaard whose philosophical attitude toward God enabled him in a neurotic way to “settle everything in the study and need not to do it in life”. In a later letter Jung reflects on this use of philosophy to bypass life in Kierkegaard, reflecting on the Danish philosopher’s broken engagement with his beloved Regine:

Reading your detailed account of Kierkegaard, I was once again struck by the discrepancy between the perpetual talk about fulfilling God’s will and reality: when God appeared to him in the shape of “Regina” he took to his heels. It was too terrible for him to have to subordinate his autocratism to the love of another person.

Ultimately Jung’s attitude towards philosophers is that they are experiencing a pathological “Hypertrophy of intellectual intuition”. He applies this diagnosis directly to Nietzsche and to Schopenhauer but presumably he’d have no problem diagnosing Kierkegaard and Heidegger with the same condition.

To summarise then Jung’s attitude towards philosophers is that they are overstepping the bounds of what is known and what emerges beyond that threshold says more about the philosopher than it does about the world. And what it says about them is usually not too flattering. What emerges is a picture of philosophers as a bunch of neurotic madmen spewing their unconscious prejudices on the world. All this seems a little one-sided so let’s take a step back now and analyse the psychoanalyst.

The Unlived Jung

In analysing what Jung has to say about the philosophers we might say that he has a philosophical point and a psychological one. The psychological one is that they’re all nuts while the philosophical one comes down to the critical threshold between what can be known and what can’t be known.

For Jung this question of what can be known is a dividing line between science and philosophy. This tension is a very personal one for Jung and exploring that tension in Jung’s psyche might just reveal why his feelings towards philosophy after Kant are so charged. Understanding this personal element in Jung’s psyche reveals an unlived life that is perhaps spilling out in Jung’s emotional dismissal.

In the autobiographical Memories Dreams Reflections Jung talks about the division in his psyche between what he called his №1 personality and his №2 personality. As a child he was aware of these two personalities and their differences:

One was the son of my parents, who went to school and was less intelligent, attentive, hardworking, decent, and clean than many other boys. The other [the №2 personality] was grown up — old, in fact — sceptical, mistrustful, remote from the world of men, but close to nature, the earth, the sun, the moon, the weather, all living creatures, and above all close to the night, to dreams, and to whatever “God” worked directly in him.

When Jung was in school and trying to decide what he would study in university he was torn between studying science on the one hand and the humane or historical studies on the other. Empiricism appealed to one side of him but meaning was what drew him to the other. He said:

“The older I grew, the more frequently I was asked by my parents and others what I wanted to be. I had no clear notions on that score. My interests drew me in different directions. On the one hand I was powerfully attracted by science, with its truths based on facts; on the other hand I was fascinated by everything to do with comparative religion. In the sciences I was drawn principally to zoology, palæontology, and geology; in the humanities to Greco-Roman, Egyptian, and prehistoric archaeology. At that time, of course, I did not realise how very much this choice of the most varied subjects corresponded to the nature of my inner dichotomy. What appealed to me in science were the concrete facts and their historical background, and in comparative religion the spiritual problems, into which philosophy also entered. In science I missed the factor of meaning; and in religion, that of empiricism. Science met, to a very large extent, the needs of №1 personality, whereas the humane or historical studies provided beneficial instruction for №2.”

Ultimately he chose the path of science but as his career developed he was drawn more and more towards the interests of №2 personality. When Jung and Freud were still cosy, and Jung was Freud’s heir apparent, the father of psychoanalysis wrote to Jung:

I know that your deepest inclinations are impelling you towards a study of the occult, and do not doubt that you will return home with a rich cargo. There is no stopping that, and it is always right for a person to follow the biddings of his own impulses. The reputation you have won with your Dementia [Freud is referring here to Jung’s highly respected work on schizophrenia which was called Dementia Praecox at the time] will stand against the charge of “mystic” for quite a while. Only don’t stay too long away from us in lush tropical colonies; it is necessary to govern at home.

Nevertheless Jung continued to feel a tension between these two personalities and their corresponding worlds. He found that if he approached the world from the perspective of №1 nature showed up as the object of scientific empirical study while from the perspective of №2 on the other hand it was experienced as the numinous and ineffable realm that he repeatedly refers to as “God’s world” in Memories, Dreams and Reflections.

Of course these forces weren’t always enemies. In fact it seems that in his period of psychotic visions between November 1913 and April 1918 that became the Red Book, it was science that kept him grounded:

My science was the only way I had of extricating myself from that chaos. Otherwise the material would have trapped me in its thicket, strangled me like jungle creepers. I took great care to try to understand every single image, every item of my psychic inventory, and to classify them scientifically — so far as this was possible — and, above all, to realize them in actual life. Jung, MDR, p. 192

A Shadow in the Looking Glass

From this brief overview of Jung’s relationship with science then we have something that’s quite revealing when it comes to his comments on the philosophers. In what Walter Kaufmann describes as Jung’s “wildly emotional overreaction” to the Existentialist philosophers we see, as Kaufmann observes, Jung’s own Shadow (though Jung himself fails to catch it on this occasion). His vitriol goes far beyond the proto-Existentialists Heidegger or Kierkegaard. As we’ve seen he goes so far as to dismiss the entire German philosophical tradition as an “intellectual perversion”

Jung’s aggressive dismissal of the philosophers may, in the end, say much more about himself than about these philosophers. Here we may have some trace of Jung’s sense of an unlived life. Jung chose the path of science but as he moved ever deeper into the waters of philosophy, spirituality and religion he found himself pulled apart on a cross. In one direction there was the desire to be a scientist and on the other to be a philosopher. The empiricism and the scepticism of the scientist always hampered his philosophical work. To use Jungian terminology his ego always wanted to be a scientist but his soul kept calling him to the humanities. Hence his words:

“I am the damnedest dilettante who ever lived. I wanted to achieve something in my science and then I was plunged in this stream of lava, and then had to classify everything.”

There was something of the insecurity of the dilettante in Jung’s comment on the philosophers who criticised his collective unconscious:

I can put up with any amount of criticism so long as it is based on facts or real knowledge. But what I have experienced in the way of philosophical criticism of my concept of the collective unconscious, for instance, was characterized by lamentable ignorance on the one hand and intellectual prejudice on the other.

It seems that Jung’s relationship with philosophy was a complicated one. It is a shrill speaking to the tension between the №1 and №2 personalities. On the one hand the scientific propensities of №1 personality hate anything that goes beyond empiricism. This part of his personality which is speaking in his criticism of the philosophers is always at tension with the other part of his psyche. Jung’s criticism of the philosophers is all the more notable since as Kaufmann put it:

“Jung boasted repeatedly that he knew philosophy in general and Nietzsche in particular as Freud did not”

In a letter where he is asked about the influence of Hegel on his thinking he responds that it is non-existent since he never read the man but insofar as he was aware of Hegel he writes that:

It was always my view that Hegel was a psychologist manqué [yet another word I had to look up; The Oxford Dictionary defines manqué as: “having failed to become what one might have been”], in much the same way as I am a philosopher manqué

Here then we see that Jung has a lot of Imposter Syndrome around his philosophical side and insofar as his work goes beyond empiricism. Of course as we’ve seen with personalities №1 and №2 this is a tension that pre-dated any specialisation in psychology. But it is an amplifying factor and, as a 67-year-old who frames it this way, there seems to be a lingering sense of what could have been.

So when we look at these philosophers, in particular Heidegger, who delve deeply into what Jung describes as “God’s world” — a realm he is fatally attracted to and indulges in himself — we may yet see Jung’s greatest fears for his own work: that it is all in fact a neurotic projection of his own “unconscious subjective prejudices”. This fear is all the more real when we consider how many people have since thrown such accusations at Jung.

But we also see perhaps one of Jung’s deeper desires to have what the dilettante always desires: recognition. One can’t help but wonder whether Jung’s shrillness betrays a jealousy on his part. Hegel, Kierkegaard and Heidegger were held in high prestige. They all made a major impact on theology and there’s no doubt that Jung wanted to do the same. But the neurotic tension of this philosophical side with his scientific personality hampered this career path. In the Red Book we find the line:

“Keep it far from me, science that clever knower, that bad prison master who binds the soul and imprisons it in a lightless cell.”

This line perhaps speaks deeply to the Shadowed tension that philosophy held for Jung.

Of course all of this isn’t to say that Jung was wrong. The claims he brought against Heidegger of his wordplay is a claim that has been brought again and again in the decades since Being and Time was published in 1928. And his assessment of Kierkegaard’s abandonment of his engagement with Regine at least to my eyes seems to have hit the nail on its neurotic head.

My argument is that Jung’s reaction to these thinkers seems to betray something about himself. There’s no charity with Heidegger — no sitting on the fence or willingness to even entertain his thoughts. It’s word salad to him and that is all it will remain. The fact that other thinkers take him seriously speaks to, as he put it with Kierkegaard, “the theological neurosis of our times” rather than a potentially genuine value. When Heidegger’s words are read out at a conference he finds them comically confusing. And then of course there’s his comparison that the likes of Heidegger are in “lunatic asylums” as both patients and overzealous practitioners. There’s no will to pass over in silence that which he does not understand. Instead he greets it with dismissal and diagnosis which while perhaps warranted in the case of Kierkegaard — who Jung seems to have read at least a little of — seems rather to speak to something deeper with Heidegger of whose biography and work he knows little to nothing. At the end of one of these letters he shows some awareness of this excess:

Excuse these blasphemies! They flow from my hygienic propensities, because I hate to see so many young minds infected by Heidegger.

That crucial final clause may tell us a lot. It’s worth noting the selection of philosophers that Jung attacks. He doesn’t go after Kant or Descartes or Spinoza though each of these might equally fall into the category of a neurotic over-stepping of boundaries. As we’ve seen Jung never read philosophy beyond Kant. Given this hole in his knowledge Jung would either have to admit to being incomplete or he could take a shortcut and dismiss the work of these philosophers as neurotic. But with Kant who is central to Jung’s work there is no such accusation though the label is just as fitting.

My suspicion is that behind Jung’s hatred of seeing “so many young minds infected by Heidegger” there may lurk a mimetic, rivalrous dynamic. We see this competitive streak in Jung’s letters to Freud about psychoanalysis taking over the psychiatric society of Switzerland and how they would take over Germany together writing:

“Your (that is, our) cause is winning all along the line, so that we had the last word, in fact we’re on top of the world.”.

To this 1909 letter Freud replied:

“Aren’t we (justifiably) childish to get so much pleasure out of every least bit of recognition, when in reality it matters so little and our ultimate conquest of the world still lies so far ahead?”

The unlived life of Jung is reflected to him through the adulation of the public. Perhaps there is a sense that it should be his own works that would be much more suitable to “infect” the young minds and that his psychological theory should be “on top of the world”. If he could only see the world today and how many people feel just this way about his work through the explosive impact of Jordan Peterson on the culture.

I’ve always thought that Peterson’s blindness to the Postmodernists was completely out of step and spirit with Jung. After this I suspect there may be a deeper temperamental similarity between them than I previously suspected.

📚 Further Reading:

– Jung, C.G. *Memories, Dreams, Reflections*

– Jung, C.G., 2012. _The red book: A reader’s edition_. WW Norton & Company.

– Jung, C.G., 2015. _Letters of CG Jung: Volume I, 1906–1950_. Routledge

– Jung, C.G., 2021. _CG Jung Letters, Volume 2: 1951–1961_. Princeton University Press

– Freud, S. and Jung, C.G., 1994. _The Freud-Jung Letters: The Correspondence Between Sigmund Freud and CG Jung_. Princeton University Press.

– Nietzsche, F., 1992. _Basic Writings of Nietzsche_. Modern Library.

– Kaufmann, W. ed., 1992. _Freud, Alder, and Jung: Discovering the Mind_. Routledge.

📫The Letters

– Arnold Kiinzli, 4 February 1943

– Arnold Kiinzli, 28 February 1943

– Arnold Kiinzli, 16 March 1943

– J. Meinertz, 3 July 1939

– Pastor Bremi, 26 December 1953

– Friedrich Seifert, 31 July 1935

– Dr. Pannwitz, 27 March 1937

3 Comments

Leave A Comment

Neurosis addles the brains of every philosopher because he is at odds with himself. His philosophy is then nothing but a systemized struggle with his own uncertainty. — Letter to Arnold Kiinzli, 28 February 1943

I came across this letter recently where Jung wrote some pretty salty things about the Existentialist philosophers Kierkegaard and Heidegger. My interest piqued I decided to search through Jung’s Collected Works and the collections of his letters to see what else the Swiss psychologist had to say about philosophers. What emerged was a fascinating picture of a man who really did not respect the Existentialist philosophers and didn’t have many kind words for philosophers in general. The opening quote is pretty typical in theme and tone of what he has to say.

The first surprising thing is that in the thousands of pages of this Collected Works and letters there is little mention of philosophers at all. Jung says a few nice things about Socrates, mentions Plato in passing a few times and the same with Kant. But despite his comment in one letter that “Philosophically I am old-fashioned enough not to have got beyond Kant” Jung has much less to say about the philosophers before Kant than he does about those after. And none of these things are particularly pleasant. He manages to hit all the major philosophers after Kant in this drive-by rampage: Hegel, Schopenhauer, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche and most of all Heidegger.

With the exception of Nietzsche and a little bit of Kierkegaard, Jung doesn’t seem to have read anything by these philosophers. Nietzsche stands out for him as a mixed bag: the German philosopher was both a troubled mind and a very inspiring Muse whose influence can be seen throughout Jung’s work.

This strained relationship between Jung and philosophy is all the more peculiar since he used to brag to Freud that he was adept at philosophy and Freud wasn’t. In this instalment we’re going to explore this unusual relationship between Jung and philosophy. In the first half of the article we’ll look at the various slanders Jung had for these philosophers. Then in the second half of the article I want to try and get under the mask. We are going to dig down on this comment to Freud and follow up on the cue of legendary Nietzsche translator Walter Kaufmann who saw the workings of Jung’s Shadow in these “wildly emotional” comments on philosophers. I will argue that Jung’s disdain for these philosophers he had little to no experience with speaks to the tension in his psyche between what he calls Personality №1 and Personality №2. This theme as we’ll see runs throughout his life and his work with the philosopher carrying the archetypal image of Jung’s unlived life.

Beyond their proper bounds

Jung’s attacks on the philosophers fall into two categories. Firstly he accuses the philosophers of going beyond their proper bounds. And secondly he accuses them, as in the opening quote, of being mentally ill.

In the first case the philosophers grind Jung’s gears by going beyond their proper bounds and being unscientific. In this vein we see that Jung’s critique doesn’t just apply to Heidegger and Kierkegaard but also to Hegel and German philosophy in general:

Moreover this whole intellectual perversion is a German national institution.

In one letter he says that he considers all speculations that go beyond our current capacities as being “a pretext for covering up one’s own infertility”. And in a later letter he speaks about the need for philosophical criticism to be grounded in factual knowledge if it’s not to “remain hanging in mid-air and thus to be condemned to sterility”.

In another letter he says that the Heideggerian school of philosophers “merely play verbal tricks”. In this letter to Josef Meinertz — the author of a book on psychotherapy and philosophy — he dismisses the way such philosophers deal with death:

An especially delectable morsel is the way the philosophers juggle with death. I can’t wait for the dissertation “How is Death Possible?” or “The Philosophical Foundations of Death.” Excuse these heretical fits of mine; they spring from practical experience, where the impotence of philosophical language is revealed at its starkest.

From what he’s gleaned from Meinertz’s work he says:

What Heidegger, Klages, and Jaspers have to say in this respect has never affected me very deeply, for one notices the same thing in all writers who have never had to wrestle with the practical problems of psychotherapy. They all have an astonishing facility with words, which they endow with an almost magical efficacy. If Klages had had to treat a single case of neurosis he would never have brought off that thick tome on the obnoxious spirit. Similarly, Heidegger would have lost all desire to juggle with words.

Jung is always aspiring to the ideal of science and philosophical criticism comes up short for him insofar as it fails to “meet all the requirements of the scientific attitude”.

Where philosophy fails to meet these requirements it becomes a mere reflection of the philosopher’s “unconscious subjective prejudices”. Given the private medium of letter-writing it’s fun to see Jung dabbling in a bit of salty language. In one letter he says that:

There is no thinking qua thinking, at times it is a pisspot of unconscious devils

And in another great line from one of the letters he writes regarding Kierkegaard’s concept of Anxiety:

The philosopher starts from the anxiety that possesses him and then, through reflection, turns his subjective state of being possessed into a perception of anxiety. Question: is it an object worthy of anxiety, or a poltroonery [a cowardly act] of the ego, shitting its pants?

Jung’s point here echoes Nietzsche’s line on the prejudices of philosophers from Beyond Good and Evil where he writes that:

“most of the conscious thinking of a philosopher is secretly guided and forced into certain channels by his instincts”

Of all the philosophers Jung holds a special place in his heart for Heidegger. Presumably at the time that most of these letters were being written in the 1930s Heidegger was coming into the fullness of his popularity. Jung writes that Heidegger “bristles” with the aforementioned “unconscious subjective prejudices” and he tries:

“in vain to hide behind a blown-up language”.

He describes Heidegger’s writing as “twaddle” and when a colleague of his read out some Heidegger at a conference he found it was “positively comic”:

The substance of what he read out was unutterably trashy and banal, and Brinkmann could just as well have done it to make Heidegger ridiculous

In summation then this is the first part of Jung’s critique of philosophers; he says that philosophy is a constant overstepping of its bounds. We could maybe call this a Kantian hygienics. He wants to keep to a scientific project of what can be known. He writes that:

Philosophy has still to learn that it is made by human beings and depends to an alarming degree on their psychic constitution

And this psychic constitution is on Jung’s account far too often and far too deeply neurotic.

A bunch of neurotics

For Jung, the philosophies of Nietzsche, Kierkegaard and Heidegger are all confessions of their own neuroticism. As we saw in the opening quote Jung puts this confessional element much more shrilly than Nietzsche:

Neurosis addles the brains of every philosopher because he is at odds with himself. His philosophy is then nothing but a systemized struggle with his own uncertainty

He launches a few broadsides at philosophers in these letters. Hegel “is fit to burst with presumption and vanity”, Nietzsche “drips with outraged sexuality”. Kierkegaard he repeatedly calls a grizzler [a term which I had to look up; grizzling it turns out means “the action, typically by a child, of crying fretfully” or as the Cambridge dictionary puts it “to cry continuously but not very loudly, or to complain all the time”; so Jung is basically calling Kierkegaard a cry-baby]. Of the Danish philosopher’s brilliance Jung writes:

“Kierkegaard was a stimulating and pioneering force precisely because of his neurosis”

True to form he holds his harshest sentiments for Heidegger going so far as to say:

Heidegger’s modus philosophandi is neurotic through and through and is ultimately rooted in his psychic crankiness. His kindred spirits, close or distant, are sitting in lunatic asylums, some as patients and some as psychiatrists on a philosophical rampage.

This neurosis is key in the content of their philosophies. Their uncertainty with themselves — the sense that they stand on ice of uncertain thickness and which may crack at any moment drowning them in the cold waters of their depths — is key to their philosophies. The doubt that such neurosis cultivates in the neurotic infects their vision of their fellow humans and of the world. As Jung puts it:

Neurosis is a justified doubt in oneself and continually poses the ultimate question of trust in man and in God. Doubt is creative if it is answered by deeds, and so is neurosis if it exonerates itself as having been a phase — a crisis which is pathological only when chronic. Neurosis is a protracted crisis degenerated into a habit, the daily catastrophe ready for use.

This neuroticism is perhaps most obvious in Kierkegaard whose philosophical attitude toward God enabled him in a neurotic way to “settle everything in the study and need not to do it in life”. In a later letter Jung reflects on this use of philosophy to bypass life in Kierkegaard, reflecting on the Danish philosopher’s broken engagement with his beloved Regine:

Reading your detailed account of Kierkegaard, I was once again struck by the discrepancy between the perpetual talk about fulfilling God’s will and reality: when God appeared to him in the shape of “Regina” he took to his heels. It was too terrible for him to have to subordinate his autocratism to the love of another person.

Ultimately Jung’s attitude towards philosophers is that they are experiencing a pathological “Hypertrophy of intellectual intuition”. He applies this diagnosis directly to Nietzsche and to Schopenhauer but presumably he’d have no problem diagnosing Kierkegaard and Heidegger with the same condition.

To summarise then Jung’s attitude towards philosophers is that they are overstepping the bounds of what is known and what emerges beyond that threshold says more about the philosopher than it does about the world. And what it says about them is usually not too flattering. What emerges is a picture of philosophers as a bunch of neurotic madmen spewing their unconscious prejudices on the world. All this seems a little one-sided so let’s take a step back now and analyse the psychoanalyst.

The Unlived Jung

In analysing what Jung has to say about the philosophers we might say that he has a philosophical point and a psychological one. The psychological one is that they’re all nuts while the philosophical one comes down to the critical threshold between what can be known and what can’t be known.

For Jung this question of what can be known is a dividing line between science and philosophy. This tension is a very personal one for Jung and exploring that tension in Jung’s psyche might just reveal why his feelings towards philosophy after Kant are so charged. Understanding this personal element in Jung’s psyche reveals an unlived life that is perhaps spilling out in Jung’s emotional dismissal.

In the autobiographical Memories Dreams Reflections Jung talks about the division in his psyche between what he called his №1 personality and his №2 personality. As a child he was aware of these two personalities and their differences:

One was the son of my parents, who went to school and was less intelligent, attentive, hardworking, decent, and clean than many other boys. The other [the №2 personality] was grown up — old, in fact — sceptical, mistrustful, remote from the world of men, but close to nature, the earth, the sun, the moon, the weather, all living creatures, and above all close to the night, to dreams, and to whatever “God” worked directly in him.

When Jung was in school and trying to decide what he would study in university he was torn between studying science on the one hand and the humane or historical studies on the other. Empiricism appealed to one side of him but meaning was what drew him to the other. He said:

“The older I grew, the more frequently I was asked by my parents and others what I wanted to be. I had no clear notions on that score. My interests drew me in different directions. On the one hand I was powerfully attracted by science, with its truths based on facts; on the other hand I was fascinated by everything to do with comparative religion. In the sciences I was drawn principally to zoology, palæontology, and geology; in the humanities to Greco-Roman, Egyptian, and prehistoric archaeology. At that time, of course, I did not realise how very much this choice of the most varied subjects corresponded to the nature of my inner dichotomy. What appealed to me in science were the concrete facts and their historical background, and in comparative religion the spiritual problems, into which philosophy also entered. In science I missed the factor of meaning; and in religion, that of empiricism. Science met, to a very large extent, the needs of №1 personality, whereas the humane or historical studies provided beneficial instruction for №2.”

Ultimately he chose the path of science but as his career developed he was drawn more and more towards the interests of №2 personality. When Jung and Freud were still cosy, and Jung was Freud’s heir apparent, the father of psychoanalysis wrote to Jung:

I know that your deepest inclinations are impelling you towards a study of the occult, and do not doubt that you will return home with a rich cargo. There is no stopping that, and it is always right for a person to follow the biddings of his own impulses. The reputation you have won with your Dementia [Freud is referring here to Jung’s highly respected work on schizophrenia which was called Dementia Praecox at the time] will stand against the charge of “mystic” for quite a while. Only don’t stay too long away from us in lush tropical colonies; it is necessary to govern at home.

Nevertheless Jung continued to feel a tension between these two personalities and their corresponding worlds. He found that if he approached the world from the perspective of №1 nature showed up as the object of scientific empirical study while from the perspective of №2 on the other hand it was experienced as the numinous and ineffable realm that he repeatedly refers to as “God’s world” in Memories, Dreams and Reflections.

Of course these forces weren’t always enemies. In fact it seems that in his period of psychotic visions between November 1913 and April 1918 that became the Red Book, it was science that kept him grounded:

My science was the only way I had of extricating myself from that chaos. Otherwise the material would have trapped me in its thicket, strangled me like jungle creepers. I took great care to try to understand every single image, every item of my psychic inventory, and to classify them scientifically — so far as this was possible — and, above all, to realize them in actual life. Jung, MDR, p. 192

A Shadow in the Looking Glass

From this brief overview of Jung’s relationship with science then we have something that’s quite revealing when it comes to his comments on the philosophers. In what Walter Kaufmann describes as Jung’s “wildly emotional overreaction” to the Existentialist philosophers we see, as Kaufmann observes, Jung’s own Shadow (though Jung himself fails to catch it on this occasion). His vitriol goes far beyond the proto-Existentialists Heidegger or Kierkegaard. As we’ve seen he goes so far as to dismiss the entire German philosophical tradition as an “intellectual perversion”

Jung’s aggressive dismissal of the philosophers may, in the end, say much more about himself than about these philosophers. Here we may have some trace of Jung’s sense of an unlived life. Jung chose the path of science but as he moved ever deeper into the waters of philosophy, spirituality and religion he found himself pulled apart on a cross. In one direction there was the desire to be a scientist and on the other to be a philosopher. The empiricism and the scepticism of the scientist always hampered his philosophical work. To use Jungian terminology his ego always wanted to be a scientist but his soul kept calling him to the humanities. Hence his words:

“I am the damnedest dilettante who ever lived. I wanted to achieve something in my science and then I was plunged in this stream of lava, and then had to classify everything.”

There was something of the insecurity of the dilettante in Jung’s comment on the philosophers who criticised his collective unconscious:

I can put up with any amount of criticism so long as it is based on facts or real knowledge. But what I have experienced in the way of philosophical criticism of my concept of the collective unconscious, for instance, was characterized by lamentable ignorance on the one hand and intellectual prejudice on the other.

It seems that Jung’s relationship with philosophy was a complicated one. It is a shrill speaking to the tension between the №1 and №2 personalities. On the one hand the scientific propensities of №1 personality hate anything that goes beyond empiricism. This part of his personality which is speaking in his criticism of the philosophers is always at tension with the other part of his psyche. Jung’s criticism of the philosophers is all the more notable since as Kaufmann put it:

“Jung boasted repeatedly that he knew philosophy in general and Nietzsche in particular as Freud did not”

In a letter where he is asked about the influence of Hegel on his thinking he responds that it is non-existent since he never read the man but insofar as he was aware of Hegel he writes that:

It was always my view that Hegel was a psychologist manqué [yet another word I had to look up; The Oxford Dictionary defines manqué as: “having failed to become what one might have been”], in much the same way as I am a philosopher manqué

Here then we see that Jung has a lot of Imposter Syndrome around his philosophical side and insofar as his work goes beyond empiricism. Of course as we’ve seen with personalities №1 and №2 this is a tension that pre-dated any specialisation in psychology. But it is an amplifying factor and, as a 67-year-old who frames it this way, there seems to be a lingering sense of what could have been.

So when we look at these philosophers, in particular Heidegger, who delve deeply into what Jung describes as “God’s world” — a realm he is fatally attracted to and indulges in himself — we may yet see Jung’s greatest fears for his own work: that it is all in fact a neurotic projection of his own “unconscious subjective prejudices”. This fear is all the more real when we consider how many people have since thrown such accusations at Jung.

But we also see perhaps one of Jung’s deeper desires to have what the dilettante always desires: recognition. One can’t help but wonder whether Jung’s shrillness betrays a jealousy on his part. Hegel, Kierkegaard and Heidegger were held in high prestige. They all made a major impact on theology and there’s no doubt that Jung wanted to do the same. But the neurotic tension of this philosophical side with his scientific personality hampered this career path. In the Red Book we find the line:

“Keep it far from me, science that clever knower, that bad prison master who binds the soul and imprisons it in a lightless cell.”

This line perhaps speaks deeply to the Shadowed tension that philosophy held for Jung.

Of course all of this isn’t to say that Jung was wrong. The claims he brought against Heidegger of his wordplay is a claim that has been brought again and again in the decades since Being and Time was published in 1928. And his assessment of Kierkegaard’s abandonment of his engagement with Regine at least to my eyes seems to have hit the nail on its neurotic head.

My argument is that Jung’s reaction to these thinkers seems to betray something about himself. There’s no charity with Heidegger — no sitting on the fence or willingness to even entertain his thoughts. It’s word salad to him and that is all it will remain. The fact that other thinkers take him seriously speaks to, as he put it with Kierkegaard, “the theological neurosis of our times” rather than a potentially genuine value. When Heidegger’s words are read out at a conference he finds them comically confusing. And then of course there’s his comparison that the likes of Heidegger are in “lunatic asylums” as both patients and overzealous practitioners. There’s no will to pass over in silence that which he does not understand. Instead he greets it with dismissal and diagnosis which while perhaps warranted in the case of Kierkegaard — who Jung seems to have read at least a little of — seems rather to speak to something deeper with Heidegger of whose biography and work he knows little to nothing. At the end of one of these letters he shows some awareness of this excess:

Excuse these blasphemies! They flow from my hygienic propensities, because I hate to see so many young minds infected by Heidegger.

That crucial final clause may tell us a lot. It’s worth noting the selection of philosophers that Jung attacks. He doesn’t go after Kant or Descartes or Spinoza though each of these might equally fall into the category of a neurotic over-stepping of boundaries. As we’ve seen Jung never read philosophy beyond Kant. Given this hole in his knowledge Jung would either have to admit to being incomplete or he could take a shortcut and dismiss the work of these philosophers as neurotic. But with Kant who is central to Jung’s work there is no such accusation though the label is just as fitting.

My suspicion is that behind Jung’s hatred of seeing “so many young minds infected by Heidegger” there may lurk a mimetic, rivalrous dynamic. We see this competitive streak in Jung’s letters to Freud about psychoanalysis taking over the psychiatric society of Switzerland and how they would take over Germany together writing:

“Your (that is, our) cause is winning all along the line, so that we had the last word, in fact we’re on top of the world.”.

To this 1909 letter Freud replied:

“Aren’t we (justifiably) childish to get so much pleasure out of every least bit of recognition, when in reality it matters so little and our ultimate conquest of the world still lies so far ahead?”

The unlived life of Jung is reflected to him through the adulation of the public. Perhaps there is a sense that it should be his own works that would be much more suitable to “infect” the young minds and that his psychological theory should be “on top of the world”. If he could only see the world today and how many people feel just this way about his work through the explosive impact of Jordan Peterson on the culture.

I’ve always thought that Peterson’s blindness to the Postmodernists was completely out of step and spirit with Jung. After this I suspect there may be a deeper temperamental similarity between them than I previously suspected.

📚 Further Reading:

– Jung, C.G. *Memories, Dreams, Reflections*

– Jung, C.G., 2012. _The red book: A reader’s edition_. WW Norton & Company.

– Jung, C.G., 2015. _Letters of CG Jung: Volume I, 1906–1950_. Routledge

– Jung, C.G., 2021. _CG Jung Letters, Volume 2: 1951–1961_. Princeton University Press

– Freud, S. and Jung, C.G., 1994. _The Freud-Jung Letters: The Correspondence Between Sigmund Freud and CG Jung_. Princeton University Press.

– Nietzsche, F., 1992. _Basic Writings of Nietzsche_. Modern Library.

– Kaufmann, W. ed., 1992. _Freud, Alder, and Jung: Discovering the Mind_. Routledge.

📫The Letters

– Arnold Kiinzli, 4 February 1943

– Arnold Kiinzli, 28 February 1943

– Arnold Kiinzli, 16 March 1943

– J. Meinertz, 3 July 1939

– Pastor Bremi, 26 December 1953

– Friedrich Seifert, 31 July 1935

– Dr. Pannwitz, 27 March 1937

3 Comments

-

I came across this on YouTube last night and thoroughly enjoyed it – learned a lot AND it was funny. Thank you.

-

really interesting discussion ….. i wonder what potential ART , writ large , might have in building bridges between these various disciplines … one look @ the red book is argument enough to show that in jung we are dealing with a true artist … also terence mckenna’s claim / observation that science is merely a ‘ minor art ‘ might be relevant here …. & if you see philosophers through the lens of an artist it could be said that they’re just being creative with words … final point : you could easily throw in to this mix jung’s reductionist readings of joyce & picasso ….

Leave A Comment

Neurosis addles the brains of every philosopher because he is at odds with himself. His philosophy is then nothing but a systemized struggle with his own uncertainty. — Letter to Arnold Kiinzli, 28 February 1943

I came across this letter recently where Jung wrote some pretty salty things about the Existentialist philosophers Kierkegaard and Heidegger. My interest piqued I decided to search through Jung’s Collected Works and the collections of his letters to see what else the Swiss psychologist had to say about philosophers. What emerged was a fascinating picture of a man who really did not respect the Existentialist philosophers and didn’t have many kind words for philosophers in general. The opening quote is pretty typical in theme and tone of what he has to say.

The first surprising thing is that in the thousands of pages of this Collected Works and letters there is little mention of philosophers at all. Jung says a few nice things about Socrates, mentions Plato in passing a few times and the same with Kant. But despite his comment in one letter that “Philosophically I am old-fashioned enough not to have got beyond Kant” Jung has much less to say about the philosophers before Kant than he does about those after. And none of these things are particularly pleasant. He manages to hit all the major philosophers after Kant in this drive-by rampage: Hegel, Schopenhauer, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche and most of all Heidegger.

With the exception of Nietzsche and a little bit of Kierkegaard, Jung doesn’t seem to have read anything by these philosophers. Nietzsche stands out for him as a mixed bag: the German philosopher was both a troubled mind and a very inspiring Muse whose influence can be seen throughout Jung’s work.

This strained relationship between Jung and philosophy is all the more peculiar since he used to brag to Freud that he was adept at philosophy and Freud wasn’t. In this instalment we’re going to explore this unusual relationship between Jung and philosophy. In the first half of the article we’ll look at the various slanders Jung had for these philosophers. Then in the second half of the article I want to try and get under the mask. We are going to dig down on this comment to Freud and follow up on the cue of legendary Nietzsche translator Walter Kaufmann who saw the workings of Jung’s Shadow in these “wildly emotional” comments on philosophers. I will argue that Jung’s disdain for these philosophers he had little to no experience with speaks to the tension in his psyche between what he calls Personality №1 and Personality №2. This theme as we’ll see runs throughout his life and his work with the philosopher carrying the archetypal image of Jung’s unlived life.

Beyond their proper bounds

Jung’s attacks on the philosophers fall into two categories. Firstly he accuses the philosophers of going beyond their proper bounds. And secondly he accuses them, as in the opening quote, of being mentally ill.

In the first case the philosophers grind Jung’s gears by going beyond their proper bounds and being unscientific. In this vein we see that Jung’s critique doesn’t just apply to Heidegger and Kierkegaard but also to Hegel and German philosophy in general:

Moreover this whole intellectual perversion is a German national institution.

In one letter he says that he considers all speculations that go beyond our current capacities as being “a pretext for covering up one’s own infertility”. And in a later letter he speaks about the need for philosophical criticism to be grounded in factual knowledge if it’s not to “remain hanging in mid-air and thus to be condemned to sterility”.

In another letter he says that the Heideggerian school of philosophers “merely play verbal tricks”. In this letter to Josef Meinertz — the author of a book on psychotherapy and philosophy — he dismisses the way such philosophers deal with death:

An especially delectable morsel is the way the philosophers juggle with death. I can’t wait for the dissertation “How is Death Possible?” or “The Philosophical Foundations of Death.” Excuse these heretical fits of mine; they spring from practical experience, where the impotence of philosophical language is revealed at its starkest.

From what he’s gleaned from Meinertz’s work he says:

What Heidegger, Klages, and Jaspers have to say in this respect has never affected me very deeply, for one notices the same thing in all writers who have never had to wrestle with the practical problems of psychotherapy. They all have an astonishing facility with words, which they endow with an almost magical efficacy. If Klages had had to treat a single case of neurosis he would never have brought off that thick tome on the obnoxious spirit. Similarly, Heidegger would have lost all desire to juggle with words.

Jung is always aspiring to the ideal of science and philosophical criticism comes up short for him insofar as it fails to “meet all the requirements of the scientific attitude”.

Where philosophy fails to meet these requirements it becomes a mere reflection of the philosopher’s “unconscious subjective prejudices”. Given the private medium of letter-writing it’s fun to see Jung dabbling in a bit of salty language. In one letter he says that:

There is no thinking qua thinking, at times it is a pisspot of unconscious devils

And in another great line from one of the letters he writes regarding Kierkegaard’s concept of Anxiety:

The philosopher starts from the anxiety that possesses him and then, through reflection, turns his subjective state of being possessed into a perception of anxiety. Question: is it an object worthy of anxiety, or a poltroonery [a cowardly act] of the ego, shitting its pants?

Jung’s point here echoes Nietzsche’s line on the prejudices of philosophers from Beyond Good and Evil where he writes that:

“most of the conscious thinking of a philosopher is secretly guided and forced into certain channels by his instincts”

Of all the philosophers Jung holds a special place in his heart for Heidegger. Presumably at the time that most of these letters were being written in the 1930s Heidegger was coming into the fullness of his popularity. Jung writes that Heidegger “bristles” with the aforementioned “unconscious subjective prejudices” and he tries:

“in vain to hide behind a blown-up language”.

He describes Heidegger’s writing as “twaddle” and when a colleague of his read out some Heidegger at a conference he found it was “positively comic”:

The substance of what he read out was unutterably trashy and banal, and Brinkmann could just as well have done it to make Heidegger ridiculous

In summation then this is the first part of Jung’s critique of philosophers; he says that philosophy is a constant overstepping of its bounds. We could maybe call this a Kantian hygienics. He wants to keep to a scientific project of what can be known. He writes that:

Philosophy has still to learn that it is made by human beings and depends to an alarming degree on their psychic constitution

And this psychic constitution is on Jung’s account far too often and far too deeply neurotic.

A bunch of neurotics

For Jung, the philosophies of Nietzsche, Kierkegaard and Heidegger are all confessions of their own neuroticism. As we saw in the opening quote Jung puts this confessional element much more shrilly than Nietzsche:

Neurosis addles the brains of every philosopher because he is at odds with himself. His philosophy is then nothing but a systemized struggle with his own uncertainty

He launches a few broadsides at philosophers in these letters. Hegel “is fit to burst with presumption and vanity”, Nietzsche “drips with outraged sexuality”. Kierkegaard he repeatedly calls a grizzler [a term which I had to look up; grizzling it turns out means “the action, typically by a child, of crying fretfully” or as the Cambridge dictionary puts it “to cry continuously but not very loudly, or to complain all the time”; so Jung is basically calling Kierkegaard a cry-baby]. Of the Danish philosopher’s brilliance Jung writes:

“Kierkegaard was a stimulating and pioneering force precisely because of his neurosis”

True to form he holds his harshest sentiments for Heidegger going so far as to say:

Heidegger’s modus philosophandi is neurotic through and through and is ultimately rooted in his psychic crankiness. His kindred spirits, close or distant, are sitting in lunatic asylums, some as patients and some as psychiatrists on a philosophical rampage.

This neurosis is key in the content of their philosophies. Their uncertainty with themselves — the sense that they stand on ice of uncertain thickness and which may crack at any moment drowning them in the cold waters of their depths — is key to their philosophies. The doubt that such neurosis cultivates in the neurotic infects their vision of their fellow humans and of the world. As Jung puts it:

Neurosis is a justified doubt in oneself and continually poses the ultimate question of trust in man and in God. Doubt is creative if it is answered by deeds, and so is neurosis if it exonerates itself as having been a phase — a crisis which is pathological only when chronic. Neurosis is a protracted crisis degenerated into a habit, the daily catastrophe ready for use.

This neuroticism is perhaps most obvious in Kierkegaard whose philosophical attitude toward God enabled him in a neurotic way to “settle everything in the study and need not to do it in life”. In a later letter Jung reflects on this use of philosophy to bypass life in Kierkegaard, reflecting on the Danish philosopher’s broken engagement with his beloved Regine:

Reading your detailed account of Kierkegaard, I was once again struck by the discrepancy between the perpetual talk about fulfilling God’s will and reality: when God appeared to him in the shape of “Regina” he took to his heels. It was too terrible for him to have to subordinate his autocratism to the love of another person.

Ultimately Jung’s attitude towards philosophers is that they are experiencing a pathological “Hypertrophy of intellectual intuition”. He applies this diagnosis directly to Nietzsche and to Schopenhauer but presumably he’d have no problem diagnosing Kierkegaard and Heidegger with the same condition.

To summarise then Jung’s attitude towards philosophers is that they are overstepping the bounds of what is known and what emerges beyond that threshold says more about the philosopher than it does about the world. And what it says about them is usually not too flattering. What emerges is a picture of philosophers as a bunch of neurotic madmen spewing their unconscious prejudices on the world. All this seems a little one-sided so let’s take a step back now and analyse the psychoanalyst.

The Unlived Jung

In analysing what Jung has to say about the philosophers we might say that he has a philosophical point and a psychological one. The psychological one is that they’re all nuts while the philosophical one comes down to the critical threshold between what can be known and what can’t be known.

For Jung this question of what can be known is a dividing line between science and philosophy. This tension is a very personal one for Jung and exploring that tension in Jung’s psyche might just reveal why his feelings towards philosophy after Kant are so charged. Understanding this personal element in Jung’s psyche reveals an unlived life that is perhaps spilling out in Jung’s emotional dismissal.

In the autobiographical Memories Dreams Reflections Jung talks about the division in his psyche between what he called his №1 personality and his №2 personality. As a child he was aware of these two personalities and their differences:

One was the son of my parents, who went to school and was less intelligent, attentive, hardworking, decent, and clean than many other boys. The other [the №2 personality] was grown up — old, in fact — sceptical, mistrustful, remote from the world of men, but close to nature, the earth, the sun, the moon, the weather, all living creatures, and above all close to the night, to dreams, and to whatever “God” worked directly in him.

When Jung was in school and trying to decide what he would study in university he was torn between studying science on the one hand and the humane or historical studies on the other. Empiricism appealed to one side of him but meaning was what drew him to the other. He said:

“The older I grew, the more frequently I was asked by my parents and others what I wanted to be. I had no clear notions on that score. My interests drew me in different directions. On the one hand I was powerfully attracted by science, with its truths based on facts; on the other hand I was fascinated by everything to do with comparative religion. In the sciences I was drawn principally to zoology, palæontology, and geology; in the humanities to Greco-Roman, Egyptian, and prehistoric archaeology. At that time, of course, I did not realise how very much this choice of the most varied subjects corresponded to the nature of my inner dichotomy. What appealed to me in science were the concrete facts and their historical background, and in comparative religion the spiritual problems, into which philosophy also entered. In science I missed the factor of meaning; and in religion, that of empiricism. Science met, to a very large extent, the needs of №1 personality, whereas the humane or historical studies provided beneficial instruction for №2.”

Ultimately he chose the path of science but as his career developed he was drawn more and more towards the interests of №2 personality. When Jung and Freud were still cosy, and Jung was Freud’s heir apparent, the father of psychoanalysis wrote to Jung:

I know that your deepest inclinations are impelling you towards a study of the occult, and do not doubt that you will return home with a rich cargo. There is no stopping that, and it is always right for a person to follow the biddings of his own impulses. The reputation you have won with your Dementia [Freud is referring here to Jung’s highly respected work on schizophrenia which was called Dementia Praecox at the time] will stand against the charge of “mystic” for quite a while. Only don’t stay too long away from us in lush tropical colonies; it is necessary to govern at home.

Nevertheless Jung continued to feel a tension between these two personalities and their corresponding worlds. He found that if he approached the world from the perspective of №1 nature showed up as the object of scientific empirical study while from the perspective of №2 on the other hand it was experienced as the numinous and ineffable realm that he repeatedly refers to as “God’s world” in Memories, Dreams and Reflections.

Of course these forces weren’t always enemies. In fact it seems that in his period of psychotic visions between November 1913 and April 1918 that became the Red Book, it was science that kept him grounded:

My science was the only way I had of extricating myself from that chaos. Otherwise the material would have trapped me in its thicket, strangled me like jungle creepers. I took great care to try to understand every single image, every item of my psychic inventory, and to classify them scientifically — so far as this was possible — and, above all, to realize them in actual life. Jung, MDR, p. 192

A Shadow in the Looking Glass

From this brief overview of Jung’s relationship with science then we have something that’s quite revealing when it comes to his comments on the philosophers. In what Walter Kaufmann describes as Jung’s “wildly emotional overreaction” to the Existentialist philosophers we see, as Kaufmann observes, Jung’s own Shadow (though Jung himself fails to catch it on this occasion). His vitriol goes far beyond the proto-Existentialists Heidegger or Kierkegaard. As we’ve seen he goes so far as to dismiss the entire German philosophical tradition as an “intellectual perversion”

Jung’s aggressive dismissal of the philosophers may, in the end, say much more about himself than about these philosophers. Here we may have some trace of Jung’s sense of an unlived life. Jung chose the path of science but as he moved ever deeper into the waters of philosophy, spirituality and religion he found himself pulled apart on a cross. In one direction there was the desire to be a scientist and on the other to be a philosopher. The empiricism and the scepticism of the scientist always hampered his philosophical work. To use Jungian terminology his ego always wanted to be a scientist but his soul kept calling him to the humanities. Hence his words:

“I am the damnedest dilettante who ever lived. I wanted to achieve something in my science and then I was plunged in this stream of lava, and then had to classify everything.”

There was something of the insecurity of the dilettante in Jung’s comment on the philosophers who criticised his collective unconscious:

I can put up with any amount of criticism so long as it is based on facts or real knowledge. But what I have experienced in the way of philosophical criticism of my concept of the collective unconscious, for instance, was characterized by lamentable ignorance on the one hand and intellectual prejudice on the other.

It seems that Jung’s relationship with philosophy was a complicated one. It is a shrill speaking to the tension between the №1 and №2 personalities. On the one hand the scientific propensities of №1 personality hate anything that goes beyond empiricism. This part of his personality which is speaking in his criticism of the philosophers is always at tension with the other part of his psyche. Jung’s criticism of the philosophers is all the more notable since as Kaufmann put it:

“Jung boasted repeatedly that he knew philosophy in general and Nietzsche in particular as Freud did not”

In a letter where he is asked about the influence of Hegel on his thinking he responds that it is non-existent since he never read the man but insofar as he was aware of Hegel he writes that:

It was always my view that Hegel was a psychologist manqué [yet another word I had to look up; The Oxford Dictionary defines manqué as: “having failed to become what one might have been”], in much the same way as I am a philosopher manqué

Here then we see that Jung has a lot of Imposter Syndrome around his philosophical side and insofar as his work goes beyond empiricism. Of course as we’ve seen with personalities №1 and №2 this is a tension that pre-dated any specialisation in psychology. But it is an amplifying factor and, as a 67-year-old who frames it this way, there seems to be a lingering sense of what could have been.

So when we look at these philosophers, in particular Heidegger, who delve deeply into what Jung describes as “God’s world” — a realm he is fatally attracted to and indulges in himself — we may yet see Jung’s greatest fears for his own work: that it is all in fact a neurotic projection of his own “unconscious subjective prejudices”. This fear is all the more real when we consider how many people have since thrown such accusations at Jung.

But we also see perhaps one of Jung’s deeper desires to have what the dilettante always desires: recognition. One can’t help but wonder whether Jung’s shrillness betrays a jealousy on his part. Hegel, Kierkegaard and Heidegger were held in high prestige. They all made a major impact on theology and there’s no doubt that Jung wanted to do the same. But the neurotic tension of this philosophical side with his scientific personality hampered this career path. In the Red Book we find the line:

“Keep it far from me, science that clever knower, that bad prison master who binds the soul and imprisons it in a lightless cell.”

This line perhaps speaks deeply to the Shadowed tension that philosophy held for Jung.

Of course all of this isn’t to say that Jung was wrong. The claims he brought against Heidegger of his wordplay is a claim that has been brought again and again in the decades since Being and Time was published in 1928. And his assessment of Kierkegaard’s abandonment of his engagement with Regine at least to my eyes seems to have hit the nail on its neurotic head.

My argument is that Jung’s reaction to these thinkers seems to betray something about himself. There’s no charity with Heidegger — no sitting on the fence or willingness to even entertain his thoughts. It’s word salad to him and that is all it will remain. The fact that other thinkers take him seriously speaks to, as he put it with Kierkegaard, “the theological neurosis of our times” rather than a potentially genuine value. When Heidegger’s words are read out at a conference he finds them comically confusing. And then of course there’s his comparison that the likes of Heidegger are in “lunatic asylums” as both patients and overzealous practitioners. There’s no will to pass over in silence that which he does not understand. Instead he greets it with dismissal and diagnosis which while perhaps warranted in the case of Kierkegaard — who Jung seems to have read at least a little of — seems rather to speak to something deeper with Heidegger of whose biography and work he knows little to nothing. At the end of one of these letters he shows some awareness of this excess:

Excuse these blasphemies! They flow from my hygienic propensities, because I hate to see so many young minds infected by Heidegger.

That crucial final clause may tell us a lot. It’s worth noting the selection of philosophers that Jung attacks. He doesn’t go after Kant or Descartes or Spinoza though each of these might equally fall into the category of a neurotic over-stepping of boundaries. As we’ve seen Jung never read philosophy beyond Kant. Given this hole in his knowledge Jung would either have to admit to being incomplete or he could take a shortcut and dismiss the work of these philosophers as neurotic. But with Kant who is central to Jung’s work there is no such accusation though the label is just as fitting.

My suspicion is that behind Jung’s hatred of seeing “so many young minds infected by Heidegger” there may lurk a mimetic, rivalrous dynamic. We see this competitive streak in Jung’s letters to Freud about psychoanalysis taking over the psychiatric society of Switzerland and how they would take over Germany together writing:

“Your (that is, our) cause is winning all along the line, so that we had the last word, in fact we’re on top of the world.”.

To this 1909 letter Freud replied:

“Aren’t we (justifiably) childish to get so much pleasure out of every least bit of recognition, when in reality it matters so little and our ultimate conquest of the world still lies so far ahead?”

The unlived life of Jung is reflected to him through the adulation of the public. Perhaps there is a sense that it should be his own works that would be much more suitable to “infect” the young minds and that his psychological theory should be “on top of the world”. If he could only see the world today and how many people feel just this way about his work through the explosive impact of Jordan Peterson on the culture.

I’ve always thought that Peterson’s blindness to the Postmodernists was completely out of step and spirit with Jung. After this I suspect there may be a deeper temperamental similarity between them than I previously suspected.

📚 Further Reading:

– Jung, C.G. *Memories, Dreams, Reflections*

– Jung, C.G., 2012. _The red book: A reader’s edition_. WW Norton & Company.

– Jung, C.G., 2015. _Letters of CG Jung: Volume I, 1906–1950_. Routledge

– Jung, C.G., 2021. _CG Jung Letters, Volume 2: 1951–1961_. Princeton University Press

– Freud, S. and Jung, C.G., 1994. _The Freud-Jung Letters: The Correspondence Between Sigmund Freud and CG Jung_. Princeton University Press.

– Nietzsche, F., 1992. _Basic Writings of Nietzsche_. Modern Library.

– Kaufmann, W. ed., 1992. _Freud, Alder, and Jung: Discovering the Mind_. Routledge.

📫The Letters

– Arnold Kiinzli, 4 February 1943

– Arnold Kiinzli, 28 February 1943

– Arnold Kiinzli, 16 March 1943

– J. Meinertz, 3 July 1939

– Pastor Bremi, 26 December 1953

– Friedrich Seifert, 31 July 1935

– Dr. Pannwitz, 27 March 1937

3 Comments

-

I came across this on YouTube last night and thoroughly enjoyed it – learned a lot AND it was funny. Thank you.

-

really interesting discussion ….. i wonder what potential ART , writ large , might have in building bridges between these various disciplines … one look @ the red book is argument enough to show that in jung we are dealing with a true artist … also terence mckenna’s claim / observation that science is merely a ‘ minor art ‘ might be relevant here …. & if you see philosophers through the lens of an artist it could be said that they’re just being creative with words … final point : you could easily throw in to this mix jung’s reductionist readings of joyce & picasso ….

I came across this on YouTube last night and thoroughly enjoyed it – learned a lot AND it was funny. Thank you.

Thanks a million Rosie! Glad you enjoyed it and always nice to have the humour recognised as well!

really interesting discussion ….. i wonder what potential ART , writ large , might have in building bridges between these various disciplines … one look @ the red book is argument enough to show that in jung we are dealing with a true artist … also terence mckenna’s claim / observation that science is merely a ‘ minor art ‘ might be relevant here …. & if you see philosophers through the lens of an artist it could be said that they’re just being creative with words … final point : you could easily throw in to this mix jung’s reductionist readings of joyce & picasso ….