We are used to the association between the religious and the guilt-ridden. Those who court the divine usually carry faces weighty with self-righteousness.

But, in the second essay of his Genealogy of Morals, Nietzsche challenges this long-standing prejudice against religions. As he put it:

“there are nobler uses for the invention of gods than for the self-crucifixion and self-violation of man”.

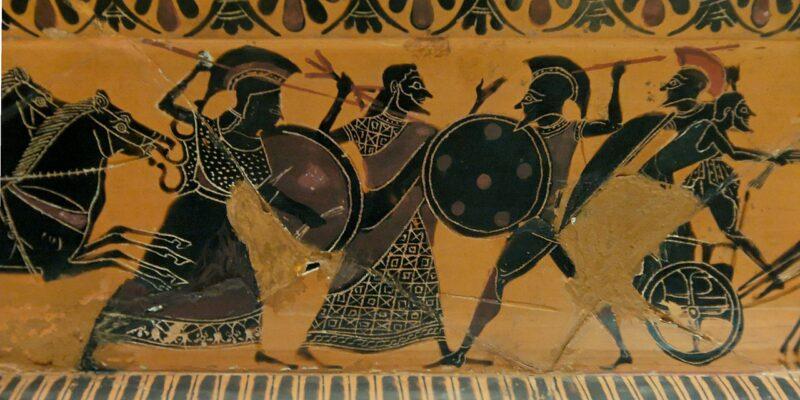

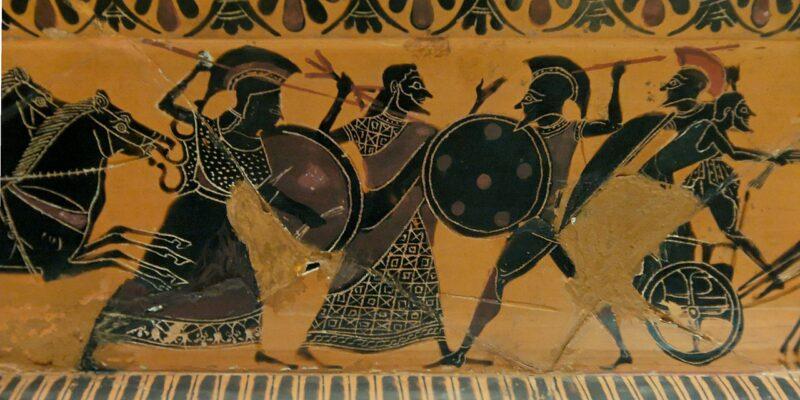

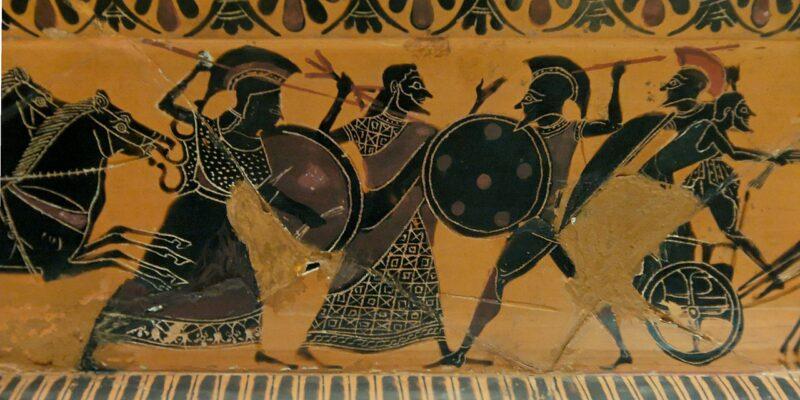

As far as guilt is concerned the Greeks are the inversions of the Judaeo-Christian tradition.

In the Judaeo-Christian tradition, the concept of God is used as an amped-up superego — he is the divine punisher for all the bad things that we humans do. If you want an explanation for all the things that go wrong in the world, look no further than your bathroom mirror. What you’ll see there is a descendant of Adam and Eve who plucked the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge and exiled themselves from the Earthly Paradise of Eden.

The responsibility for evil lies with humanity — we made the choice and now we suffer the consequences. In the Christian tradition, God is the all-good, all-loving divinity who wants more than anything to forgive you — who wants more than anything for you to be good and to do the right thing. But like a good parent, he doesn’t want to dominate you and force you to do good; he lets you make the choice. Free Will is God’s gambit — it’s his way of letting you choose your own path and while he may want you to do good he will not force you to do so. The burden of guilt then rests with humanity — rests with you. You are responsible. God is good and so lets you make your choice; God is also just and so he punishes or rewards based on your choice. But remember — you chose it.

The Ancient Greek Version of Guilt

The Greeks put the concept of godhood to a different use. In The Genealogy of Morals Nietzsche writes that in stark contrast to the Judaeo-Christian tradition: “these Greeks used their gods precisely so as to ward off the “bad conscience,””.

So how did the Greeks pull this off? They did it by putting the onus of guilt on the gods. Take Herakles for example. Herakles does something terrible — he murdered his wife and his children. This is the event that sends him off on his legendary Twelve Labours. But if we read the Greek descriptions of the story, Herakles isn’t some brutal monster in the Greek tradition. Instead, what we read is that:

The goddess Hera, determined to make trouble for Hercules, made him lose his mind. In a confused and angry state, he killed his own wife and children.

In the Old Testament we have the Book of Job where a good man Job finds his life in ruins and is left to dissect his life with his friends to evaluate whether he took some step out of line that displeased God. The onus of guilt is on Job.

Here we have Herakles. Herakles has murdered his family. But it’s not Herakles’s fault — Hera made him lose his mind. Herakles isn’t responsible, he is the victim of his father’s jealous wife. Zeus goes off on one of his adulterous side-quests, has a child and that child gets a rough-ass life because of Zeus’s dirty deeds.

Herakles’s bad deed and his punishment of twelve years of service and Twelve Labours has nothing to do with Herakles — it has to do with infighting amongst the gods. This is how as Nietzsche writes “these Greeks used their gods precisely so as to ward off the “bad conscience””.

Concluding this passage on the Greek gods Nietzsche writes:

“This expedient is typical of the Greeks…In this way the gods served in those days to justify man to a certain extent even in his wickedness,served as the originators of evil—in those days they took upon themselves, not the punishment but, what is nobler, the guilt”

Whether it’s the explanation for Herakles’s labours or for the Trojan War, the relationship of the Greeks to their gods is consistent. The gods are not self-righteous judges raining guilt on the sordid humans; they are the source of human woes (and boons). They are the guilty; we just have to honour them and live with the downstream consequences of their dramatics.

In the Context of Our Recent Explorations

This relationship with the Gods holds an interesting place in our recent explorations. In a recent instalment we talked about Foucault’s conception of Power and at the end we talked briefly about how we might map a series of force relations over onto the Jungian realm of the archetypal gods.

What we can see here is that the force relations of Greek culture constituted an entirely different power structure. The relationship of mankind to divinity is not always the relationship of superego to ego. In this case we find that the realm of the gods can be used as a justification of the id. As Nietzsche put it:

Greek gods, those reflections of noble and autocratic men, in whom the animal in man felt deified and did not lacerate itself, did not rage against itself!

The point here isn’t to fathom how people could believe in such things. As Jung sees it: “the whole of mythology could be seen as a sort of projection of the collective unconscious”. These myths then aren’t deluded stories told by the naive or manipulated by the powerful, they are reflections of the internal collective structure (the third quadrant for those who have read the article on Wilber’s Four Quadrants model) of a society.

What we can see from Nietzsche’s exploration is that the gods can be utilised not merely to maximise guilt but to relieve it. Gods are golden strings that can wrench the hearts of a people. The uses of these gods are not singular as our over-familiarity with the Christian tradition might lead us to blindly assume; as Nietzsche reveals the uses of the gods are many.

They can act as amplifiers of responsibility as the Hebrew god does, as inciters to charity as the Christian god does, or as enforcers of humility (see: hubris) and liberators of the soul as with the Greek gods.

Each way has its costs and benefits. The Hebrew system has to be admired for its audacity. It puts an unreal emphasis on the agency of man — to take the weight of all guilt on your shoulders, to believe that the ego has that much power this is an admirable (if psychologically inaccurate) perspective to cultivate. The Greek attitude on the other hand must be admired for its cultivation of acceptance. The Greeks are liberated from the onus of guilt and can instead accept that some things happen that are outside of our control and that is fine as well.

Sources:

- Nietzsche, F., 1989. On the Genealogy of Morals, trans. Walter Kaufmann. Basic Writings of Nietzsche, pp.437-599.

- The Labors of Hercules. [online] Available at: http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/Herakles/labors.html

One Comment

Leave A Comment

We are used to the association between the religious and the guilt-ridden. Those who court the divine usually carry faces weighty with self-righteousness.

But, in the second essay of his Genealogy of Morals, Nietzsche challenges this long-standing prejudice against religions. As he put it:

“there are nobler uses for the invention of gods than for the self-crucifixion and self-violation of man”.

As far as guilt is concerned the Greeks are the inversions of the Judaeo-Christian tradition.

In the Judaeo-Christian tradition, the concept of God is used as an amped-up superego — he is the divine punisher for all the bad things that we humans do. If you want an explanation for all the things that go wrong in the world, look no further than your bathroom mirror. What you’ll see there is a descendant of Adam and Eve who plucked the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge and exiled themselves from the Earthly Paradise of Eden.

The responsibility for evil lies with humanity — we made the choice and now we suffer the consequences. In the Christian tradition, God is the all-good, all-loving divinity who wants more than anything to forgive you — who wants more than anything for you to be good and to do the right thing. But like a good parent, he doesn’t want to dominate you and force you to do good; he lets you make the choice. Free Will is God’s gambit — it’s his way of letting you choose your own path and while he may want you to do good he will not force you to do so. The burden of guilt then rests with humanity — rests with you. You are responsible. God is good and so lets you make your choice; God is also just and so he punishes or rewards based on your choice. But remember — you chose it.

The Ancient Greek Version of Guilt

The Greeks put the concept of godhood to a different use. In The Genealogy of Morals Nietzsche writes that in stark contrast to the Judaeo-Christian tradition: “these Greeks used their gods precisely so as to ward off the “bad conscience,””.

So how did the Greeks pull this off? They did it by putting the onus of guilt on the gods. Take Herakles for example. Herakles does something terrible — he murdered his wife and his children. This is the event that sends him off on his legendary Twelve Labours. But if we read the Greek descriptions of the story, Herakles isn’t some brutal monster in the Greek tradition. Instead, what we read is that:

The goddess Hera, determined to make trouble for Hercules, made him lose his mind. In a confused and angry state, he killed his own wife and children.

In the Old Testament we have the Book of Job where a good man Job finds his life in ruins and is left to dissect his life with his friends to evaluate whether he took some step out of line that displeased God. The onus of guilt is on Job.

Here we have Herakles. Herakles has murdered his family. But it’s not Herakles’s fault — Hera made him lose his mind. Herakles isn’t responsible, he is the victim of his father’s jealous wife. Zeus goes off on one of his adulterous side-quests, has a child and that child gets a rough-ass life because of Zeus’s dirty deeds.

Herakles’s bad deed and his punishment of twelve years of service and Twelve Labours has nothing to do with Herakles — it has to do with infighting amongst the gods. This is how as Nietzsche writes “these Greeks used their gods precisely so as to ward off the “bad conscience””.

Concluding this passage on the Greek gods Nietzsche writes:

“This expedient is typical of the Greeks…In this way the gods served in those days to justify man to a certain extent even in his wickedness,served as the originators of evil—in those days they took upon themselves, not the punishment but, what is nobler, the guilt”

Whether it’s the explanation for Herakles’s labours or for the Trojan War, the relationship of the Greeks to their gods is consistent. The gods are not self-righteous judges raining guilt on the sordid humans; they are the source of human woes (and boons). They are the guilty; we just have to honour them and live with the downstream consequences of their dramatics.

In the Context of Our Recent Explorations

This relationship with the Gods holds an interesting place in our recent explorations. In a recent instalment we talked about Foucault’s conception of Power and at the end we talked briefly about how we might map a series of force relations over onto the Jungian realm of the archetypal gods.

What we can see here is that the force relations of Greek culture constituted an entirely different power structure. The relationship of mankind to divinity is not always the relationship of superego to ego. In this case we find that the realm of the gods can be used as a justification of the id. As Nietzsche put it:

Greek gods, those reflections of noble and autocratic men, in whom the animal in man felt deified and did not lacerate itself, did not rage against itself!

The point here isn’t to fathom how people could believe in such things. As Jung sees it: “the whole of mythology could be seen as a sort of projection of the collective unconscious”. These myths then aren’t deluded stories told by the naive or manipulated by the powerful, they are reflections of the internal collective structure (the third quadrant for those who have read the article on Wilber’s Four Quadrants model) of a society.

What we can see from Nietzsche’s exploration is that the gods can be utilised not merely to maximise guilt but to relieve it. Gods are golden strings that can wrench the hearts of a people. The uses of these gods are not singular as our over-familiarity with the Christian tradition might lead us to blindly assume; as Nietzsche reveals the uses of the gods are many.

They can act as amplifiers of responsibility as the Hebrew god does, as inciters to charity as the Christian god does, or as enforcers of humility (see: hubris) and liberators of the soul as with the Greek gods.

Each way has its costs and benefits. The Hebrew system has to be admired for its audacity. It puts an unreal emphasis on the agency of man — to take the weight of all guilt on your shoulders, to believe that the ego has that much power this is an admirable (if psychologically inaccurate) perspective to cultivate. The Greek attitude on the other hand must be admired for its cultivation of acceptance. The Greeks are liberated from the onus of guilt and can instead accept that some things happen that are outside of our control and that is fine as well.

Sources:

- Nietzsche, F., 1989. On the Genealogy of Morals, trans. Walter Kaufmann. Basic Writings of Nietzsche, pp.437-599.

- The Labors of Hercules. [online] Available at: http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/Herakles/labors.html

One Comment

-

[…] as the “Father of Existentialism”. But unlike many of his Existentialist peers from Nietzsche to Camus, Kierkegaard was not an atheist. He was a devout […]

Leave A Comment

We are used to the association between the religious and the guilt-ridden. Those who court the divine usually carry faces weighty with self-righteousness.

But, in the second essay of his Genealogy of Morals, Nietzsche challenges this long-standing prejudice against religions. As he put it:

“there are nobler uses for the invention of gods than for the self-crucifixion and self-violation of man”.

As far as guilt is concerned the Greeks are the inversions of the Judaeo-Christian tradition.

In the Judaeo-Christian tradition, the concept of God is used as an amped-up superego — he is the divine punisher for all the bad things that we humans do. If you want an explanation for all the things that go wrong in the world, look no further than your bathroom mirror. What you’ll see there is a descendant of Adam and Eve who plucked the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge and exiled themselves from the Earthly Paradise of Eden.

The responsibility for evil lies with humanity — we made the choice and now we suffer the consequences. In the Christian tradition, God is the all-good, all-loving divinity who wants more than anything to forgive you — who wants more than anything for you to be good and to do the right thing. But like a good parent, he doesn’t want to dominate you and force you to do good; he lets you make the choice. Free Will is God’s gambit — it’s his way of letting you choose your own path and while he may want you to do good he will not force you to do so. The burden of guilt then rests with humanity — rests with you. You are responsible. God is good and so lets you make your choice; God is also just and so he punishes or rewards based on your choice. But remember — you chose it.

The Ancient Greek Version of Guilt

The Greeks put the concept of godhood to a different use. In The Genealogy of Morals Nietzsche writes that in stark contrast to the Judaeo-Christian tradition: “these Greeks used their gods precisely so as to ward off the “bad conscience,””.

So how did the Greeks pull this off? They did it by putting the onus of guilt on the gods. Take Herakles for example. Herakles does something terrible — he murdered his wife and his children. This is the event that sends him off on his legendary Twelve Labours. But if we read the Greek descriptions of the story, Herakles isn’t some brutal monster in the Greek tradition. Instead, what we read is that:

The goddess Hera, determined to make trouble for Hercules, made him lose his mind. In a confused and angry state, he killed his own wife and children.

In the Old Testament we have the Book of Job where a good man Job finds his life in ruins and is left to dissect his life with his friends to evaluate whether he took some step out of line that displeased God. The onus of guilt is on Job.

Here we have Herakles. Herakles has murdered his family. But it’s not Herakles’s fault — Hera made him lose his mind. Herakles isn’t responsible, he is the victim of his father’s jealous wife. Zeus goes off on one of his adulterous side-quests, has a child and that child gets a rough-ass life because of Zeus’s dirty deeds.

Herakles’s bad deed and his punishment of twelve years of service and Twelve Labours has nothing to do with Herakles — it has to do with infighting amongst the gods. This is how as Nietzsche writes “these Greeks used their gods precisely so as to ward off the “bad conscience””.

Concluding this passage on the Greek gods Nietzsche writes:

“This expedient is typical of the Greeks…In this way the gods served in those days to justify man to a certain extent even in his wickedness,served as the originators of evil—in those days they took upon themselves, not the punishment but, what is nobler, the guilt”

Whether it’s the explanation for Herakles’s labours or for the Trojan War, the relationship of the Greeks to their gods is consistent. The gods are not self-righteous judges raining guilt on the sordid humans; they are the source of human woes (and boons). They are the guilty; we just have to honour them and live with the downstream consequences of their dramatics.

In the Context of Our Recent Explorations

This relationship with the Gods holds an interesting place in our recent explorations. In a recent instalment we talked about Foucault’s conception of Power and at the end we talked briefly about how we might map a series of force relations over onto the Jungian realm of the archetypal gods.

What we can see here is that the force relations of Greek culture constituted an entirely different power structure. The relationship of mankind to divinity is not always the relationship of superego to ego. In this case we find that the realm of the gods can be used as a justification of the id. As Nietzsche put it:

Greek gods, those reflections of noble and autocratic men, in whom the animal in man felt deified and did not lacerate itself, did not rage against itself!

The point here isn’t to fathom how people could believe in such things. As Jung sees it: “the whole of mythology could be seen as a sort of projection of the collective unconscious”. These myths then aren’t deluded stories told by the naive or manipulated by the powerful, they are reflections of the internal collective structure (the third quadrant for those who have read the article on Wilber’s Four Quadrants model) of a society.

What we can see from Nietzsche’s exploration is that the gods can be utilised not merely to maximise guilt but to relieve it. Gods are golden strings that can wrench the hearts of a people. The uses of these gods are not singular as our over-familiarity with the Christian tradition might lead us to blindly assume; as Nietzsche reveals the uses of the gods are many.

They can act as amplifiers of responsibility as the Hebrew god does, as inciters to charity as the Christian god does, or as enforcers of humility (see: hubris) and liberators of the soul as with the Greek gods.

Each way has its costs and benefits. The Hebrew system has to be admired for its audacity. It puts an unreal emphasis on the agency of man — to take the weight of all guilt on your shoulders, to believe that the ego has that much power this is an admirable (if psychologically inaccurate) perspective to cultivate. The Greek attitude on the other hand must be admired for its cultivation of acceptance. The Greeks are liberated from the onus of guilt and can instead accept that some things happen that are outside of our control and that is fine as well.

Sources:

- Nietzsche, F., 1989. On the Genealogy of Morals, trans. Walter Kaufmann. Basic Writings of Nietzsche, pp.437-599.

- The Labors of Hercules. [online] Available at: http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/Herakles/labors.html

One Comment

-

[…] as the “Father of Existentialism”. But unlike many of his Existentialist peers from Nietzsche to Camus, Kierkegaard was not an atheist. He was a devout […]

[…] as the “Father of Existentialism”. But unlike many of his Existentialist peers from Nietzsche to Camus, Kierkegaard was not an atheist. He was a devout […]