― Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra

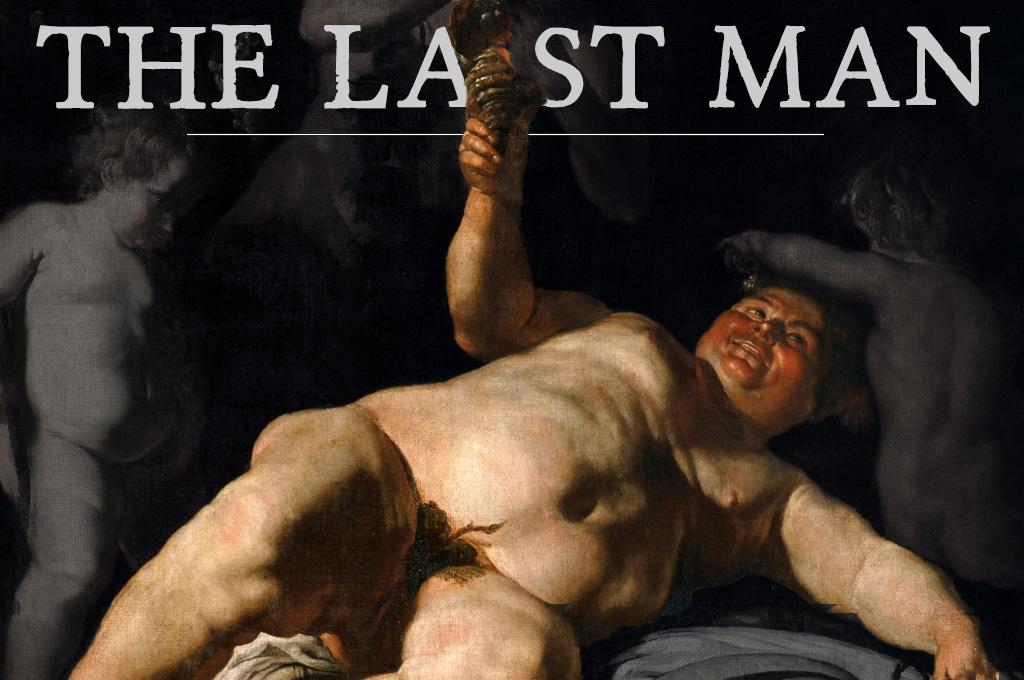

It is important in life that we have not just heroes but anti-heroes. We know who we are not just by what we are moving towards, but by what we are moving away from. In previous instalments we have talked a lot about Nietzsche’s ideal; we’ve looked at his life-affirming Dionysian ideal in a couple of articles and we looked at the stages of the development of his Übermensch in the Three Metamorphoses article.

But Nietzsche also has a counter-ideal and the name of this counter-ideal is “The Last Man”. This counter-ideal is articulated most thoroughly in the same place as his ideal — in the book for all and for none — Thus Spoke Zarathustra. There we find the Last Man introduced in sharp and eternal contrast with Nietzsche’s ideal — the Übermensch.

These two poles — the Übermensch and the Last Man are two responses to the death of God. In the ruins of the transcendent values, Nietzsche could only see two options — firstly the existential creation of our own values (which in Nietzsche takes on a Dionysian Darwinian tonality) or secondly, over against this path of health and challenge, there is the path of comfort, pleasure and the easy life i.e. the way of the Last Man.

This outlook of Nietzsche seems counterintuitive and alien at first sight — in no small part due to the strange Zarathustran package in which it comes wrapped. But fast forward to the 21st century and modern psychology — coming to terms as it is with the Mental Health crisis — suggests there may be something not just to Nietzsche’s warning about the Last Man but to his solution in the Übermensch.

The Last Man in Zarathustra

Feeling the sting of this disdain Zarathustra reflects to himself:

“There they stand,” he said to his heart; “there they laugh. They do not understand me; I am not the mouth for these ears. Must one smash their ears before they learn to listen with their eyes? Must one clatter like kettledrums and preachers of repentance? Or do they believe only the stammerer?

And it is at this point that he decides to try a different tactic. Instead of scolding them and pushing them to what they could be, i.e. the Übermensch, he goes the opposite way:

Let me then address their pride. Let me speak to them of what is most contemptible: but that is the last man.

And from here he embarks on his great warning of the trap of modern life. This warning dovetails well with his idea of the Herd and with Kierkegaard’s idea of the Crowd. This trap has emerged with the rise of modernity and the great mass production of human potential. The trap that Nietzsche is trying to warn us of is the temptation of an easy life.

With the death of God we stand at a crossroads. As we’ve talked about repeatedly on The Living Philosophy the death of God is both a dreadful curse but also a potentially abundant blessing. As well as a great danger there is a great potential. He writes:

“we philosophers and “free spirits .. feel, when we hear the news that “the old god is dead,” as if a new dawn shone on us; our heart overflows with gratitude, amazement, premonitions, expectation. At long last the horizon appears free to us again, even if it should not be bright; at long last our ships may venture out again, venture out to face any danger; all the daring of the lover of knowledge is permitted again; the sea, our sea, lies open again; perhaps there has never yet been such an ”open sea!””

But the flip side of this great potential is a great danger. In the language of the previous instalment with the death of God we have entered liminal space; of this liminality we can make either utopia or dystopia: Übermensch or Last Man.

As it stands the soil of our culture can still produce the towering canopies of human greatness but it will not always be this way. He writes:

“The time has come for man to set himself a goal. The time has come for man to plant the seed of his highest hope. His soil is still rich enough. But one day this soil will be poor and domesticated, and no tall tree will be able to grow in it. Alas, the time is coming when man will no longer shoot the arrow of his longing beyond man, and the string of his bow will have forgotten how to whir!”

Clearly Nietzsche’s preference is for the arrow that will go beyond man. But let’s take an in-depth look now at the alternative.

The Values of the Last Man

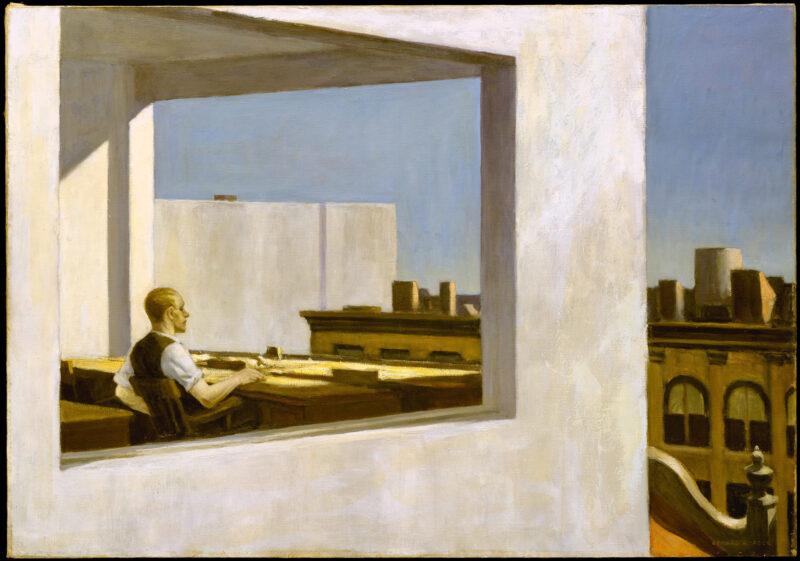

The unifying theme of the Last Man’s value system is comfort. Everything that he does is for the sake of having an easy life. The Last Man doesn’t want to overexert himself; he never strays far from the equilibrium of comfort.

“One no longer becomes poor or rich: both require too much exertion. Who still wants to rule? Who obey? Both require too much exertion.”

Entertainment is important but the Last Man is careful “less the entertainment be too harrowing”. This drive for comfort has even led to changes in where they live:

“They have left the regions where it was hard to live, for one needs warmth. One still loves one’s neighbor and rubs against him, for one needs warmth.”

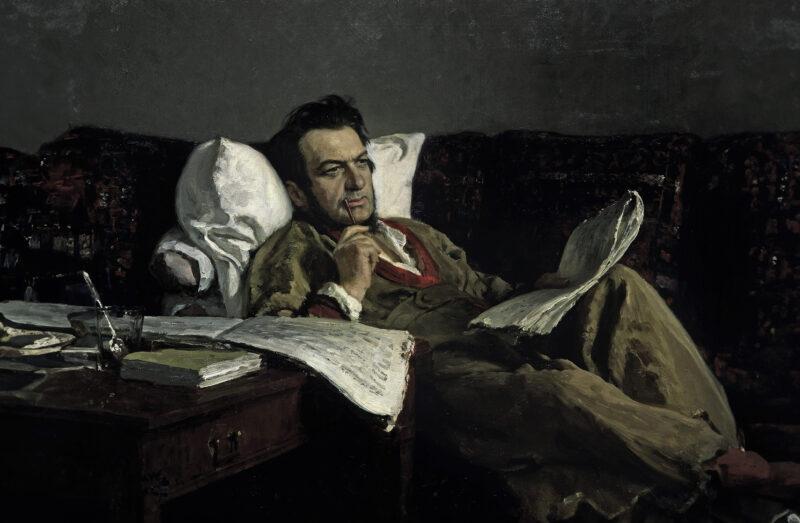

Going with this there is the pacification of the Last Man with intoxicants and little helpers — within reason of course:

“One has one’s little pleasure for the day and one’s little pleasure for the night: but one has a regard for health. […] A little poison now and then: that makes for agreeable dreams. And much poison in the end, for an agreeable death.”

This need for comfort shows up as a need for harmony in interpersonal relationships:

“Becoming sick and harboring suspicion are sinful to them: one proceeds carefully. […] One still quarrels, but one is soon reconciled—else it might spoil the digestion.”

And it shows up socially in the form of egalitarianism and democratic ideals:

“No shepherd and one herd! Everybody wants the same, everybody is the same: whoever feels different goes voluntarily into a madhouse.

“‘Formerly, all the world was mad,’ say the most refined, and they blink.

To the Last Man this seems like Utopia; twice in Zarathustra’s speech they say

“We have invented happiness, and they blink”

This blinking in these quotes is repeated a number of times in this passage on the Last Man. It puts us in mind of some docile animal. Just what animal Nietzsche has in mind seems to be revealed from the reaction of the crowd, who, having dismissed Zarathustra’s message:

“jubilated and clucked with their tongues”

So it seems that what Nietzsche wants us to think of when it comes to the Last Man then is of a flock of chickens. This also fits with the imagery of the warmth:

“One still loves one’s neighbor and rubs against him, for one needs warmth.”

The impression Nietzsche leaves us with is that the Last Man is a docile domesticated animal — an idea reinforced by the phrase he uses about the soil in the passage we quoted earlier; when the soil has lost its richness it hasn’t simply become poor but “poor and domesticated”.

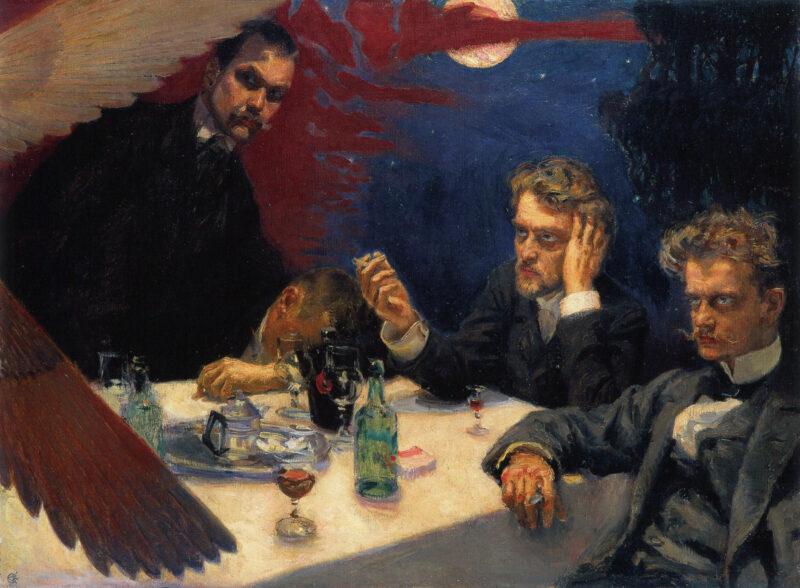

This theme of domestication is important then. It fits with Nietzsche’s disdain for the Herd which itself is connected with his idea of Slave Morality. Nietzsche doesn’t want a humanity of herd animals — of chickens or cows. To him these animals are prey animals. They are not the apex of life but the bottom feeders. They are the fodder which sustain the great birds of prey. They are necessary as a foundation for greatness but they are far from being the goal in themselves.

In The Gay Science Nietzsche writes that “Morality is the herd-instinct in the individual.” And in The Genealogy of Morals he contrasts lambs — the embodiments of Slave Morality — with birds of prey. To the lambs the birds of prey are simply evil. But the bird of prey suffers from no such moralistic qualms. Instead they reply:

“We have nothing against these good lambs; in fact, we love them; nothing tastes better than a tender lamb.”

So this predator and prey distinction then is another way of framing Nietzsche’s idea of the ideal Übermensch and the counter-ideal the Last Man. He sees an opportunity for humanity to soar but it requires leaving behind the herd or preying on the herd.

To the vast majority of us this isn’t the kind of ideal we want to embody in our lives. But there is still much to be learned from the idea of the Last Man and his antipode the Übermensch.

The Prophetic Truth of the Last Man?

Most of us go through life feeling too busy, too stressed, too put upon. We dream of retirement and of our day of rest. We dream of the day we can put down the cup and just take it easy. The idea of a life of comfort — where we work as much as we want to work and we don’t fall out with our neighbour and we have a little pleasure and an easy death — this is the kind of life we usually associate with utopia.

This life has even become possible with the technological evolutions of modern times. Indeed this is the exact promise that modern society dangles like a carrot in front of us. From Tim Ferriss’s insanely popular idea of the 4-Hour Workweek to all the products which are meant to make our lives easier like air conditioning, dishwashers and the million and one apps on our phones and our computers — there is a sprawling modern marketplace nurturing and milking this dream that Nietzsche calls the Last Man.

But there are many reasons to believe that this dream would in fact be a nightmare and would be the perfect fulfilment of Oscar Wilde’s pithy epigram that

In this world there are only two tragedies. One is not getting what one wants, and the other is getting it. The last is much the worst, the last is the real tragedy

In the century and a half since Zarathustra burst on the scene, Nietzsche’s insight into the nightmare of the Last Man has bubbled from its Zarathustran depths to the surface of cultural consciousness.

In his novel Brave New World Aldous Huxley paints the picture of a society where pain has ceased to exist, where negative emotions are washed away by the wonder-drug Soma, where life is comfortable and everybody is happy. Our knee-jerk reaction to this image is one of wonder and hope — this must be utopia. But the reality is anything but.

In the erasure of negative emotions something fundamental to the human experience is lost. There’s a scene in the book which cuts to the core of this something missing. The protagonist of Brave New World is a savage called John who was raised in a tribe outside the technological utopia. In this scene John is brought before Mustapha Mond — the Resident World Controller of Western Europe — for starting a riot as he attempted to stop the distribution of the wonder drug soma. Mond explains to John the workings of this utopian system and how it has made life comfortable and predictable.

‘But I don’t want comfort’ replies John

I want God, I want poetry, I want real danger, I want freedom, I want goodness. I want sin.’

‘In fact,’ said Mustapha Mond, ‘you’re claiming the right to be unhappy. Not to mention the right to grow old and ugly and impotent; the right to have syphilis and cancer, the right to have too little to eat; the right to be lousy; the right to live in constant apprehension of what may happen tomorrow; the right to catch typhoid; the right to be tortured by unspeakable pains of every kind.’ There was a long silence.

‘I claim them all,’ said the Savage at last.

Mustapha Mond shrugged his shoulders. ‘You’re welcome,’ he said.

This idea hasn’t just taken root in fiction but has become an emerging fact of psychology. In his book What Doesn’t Kill Us Professor Stephen Joseph unpacks the exploration in recent decades of Post-Traumatic Growth — whereby the experience of trauma can actually improve someone’s life rather than ruin it. There has also been a lot of work in the psychological study of mindsets which Kelly McGonigal’s book The Upside of Stress does a great job of exploring — bringing together as it does the studies which show that stress can make us happier healthier and more connected.

And on the flip side there is the stark reality of the mental health crisis. In his 2002 work Authentic Happiness, the father of Positive Psychology Martin Seligman noted that:

“Mounting over the last forty years in every wealthy country on the globe, there has been a startling increase in depression. Depression is now ten times as prevalent as it was in 1960, and it strikes at a much younger age. The mean age of a person’s first episode of depression forty years ago was 29.5, while today it is 14.5 years. This is a paradox, since every objective indicator of well-being—purchasing power, amount of education, availability of music, and nutrition—has been going north, while every indicator of subjective well-being has been going south. How is this epidemic to be explained?”

In the two decades since Seligman’s work was published the situation has gone from bad to much much worse.

So while we may not want to go full amoral bird of prey on our fellow humans, all of this suggests that there is at least something in Nietzsche’s warning about the Last Man which we should pay close attention to. We may want to learn a little mistrust for our comfort cravings.

The desire for the easy life speaks to a weariness with life. We are run ragged and worn down and we have lost our zest for the peaks. Instead of the challenge of the climb we crave the rest of the valley; instead of growth and truth we want comfort. But as we would learn if we were ever cursed with the tragedy of our wish being granted — comfort is its own form of hell.

― Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra

It is important in life that we have not just heroes but anti-heroes. We know who we are not just by what we are moving towards, but by what we are moving away from. In previous instalments we have talked a lot about Nietzsche’s ideal; we’ve looked at his life-affirming Dionysian ideal in a couple of articles and we looked at the stages of the development of his Übermensch in the Three Metamorphoses article.

But Nietzsche also has a counter-ideal and the name of this counter-ideal is “The Last Man”. This counter-ideal is articulated most thoroughly in the same place as his ideal — in the book for all and for none — Thus Spoke Zarathustra. There we find the Last Man introduced in sharp and eternal contrast with Nietzsche’s ideal — the Übermensch.

These two poles — the Übermensch and the Last Man are two responses to the death of God. In the ruins of the transcendent values, Nietzsche could only see two options — firstly the existential creation of our own values (which in Nietzsche takes on a Dionysian Darwinian tonality) or secondly, over against this path of health and challenge, there is the path of comfort, pleasure and the easy life i.e. the way of the Last Man.

This outlook of Nietzsche seems counterintuitive and alien at first sight — in no small part due to the strange Zarathustran package in which it comes wrapped. But fast forward to the 21st century and modern psychology — coming to terms as it is with the Mental Health crisis — suggests there may be something not just to Nietzsche’s warning about the Last Man but to his solution in the Übermensch.

The Last Man in Zarathustra

Feeling the sting of this disdain Zarathustra reflects to himself:

“There they stand,” he said to his heart; “there they laugh. They do not understand me; I am not the mouth for these ears. Must one smash their ears before they learn to listen with their eyes? Must one clatter like kettledrums and preachers of repentance? Or do they believe only the stammerer?

And it is at this point that he decides to try a different tactic. Instead of scolding them and pushing them to what they could be, i.e. the Übermensch, he goes the opposite way:

Let me then address their pride. Let me speak to them of what is most contemptible: but that is the last man.

And from here he embarks on his great warning of the trap of modern life. This warning dovetails well with his idea of the Herd and with Kierkegaard’s idea of the Crowd. This trap has emerged with the rise of modernity and the great mass production of human potential. The trap that Nietzsche is trying to warn us of is the temptation of an easy life.

With the death of God we stand at a crossroads. As we’ve talked about repeatedly on The Living Philosophy the death of God is both a dreadful curse but also a potentially abundant blessing. As well as a great danger there is a great potential. He writes:

“we philosophers and “free spirits .. feel, when we hear the news that “the old god is dead,” as if a new dawn shone on us; our heart overflows with gratitude, amazement, premonitions, expectation. At long last the horizon appears free to us again, even if it should not be bright; at long last our ships may venture out again, venture out to face any danger; all the daring of the lover of knowledge is permitted again; the sea, our sea, lies open again; perhaps there has never yet been such an ”open sea!””

But the flip side of this great potential is a great danger. In the language of the previous instalment with the death of God we have entered liminal space; of this liminality we can make either utopia or dystopia: Übermensch or Last Man.

As it stands the soil of our culture can still produce the towering canopies of human greatness but it will not always be this way. He writes:

“The time has come for man to set himself a goal. The time has come for man to plant the seed of his highest hope. His soil is still rich enough. But one day this soil will be poor and domesticated, and no tall tree will be able to grow in it. Alas, the time is coming when man will no longer shoot the arrow of his longing beyond man, and the string of his bow will have forgotten how to whir!”

Clearly Nietzsche’s preference is for the arrow that will go beyond man. But let’s take an in-depth look now at the alternative.

The Values of the Last Man

The unifying theme of the Last Man’s value system is comfort. Everything that he does is for the sake of having an easy life. The Last Man doesn’t want to overexert himself; he never strays far from the equilibrium of comfort.

“One no longer becomes poor or rich: both require too much exertion. Who still wants to rule? Who obey? Both require too much exertion.”

Entertainment is important but the Last Man is careful “less the entertainment be too harrowing”. This drive for comfort has even led to changes in where they live:

“They have left the regions where it was hard to live, for one needs warmth. One still loves one’s neighbor and rubs against him, for one needs warmth.”

Going with this there is the pacification of the Last Man with intoxicants and little helpers — within reason of course:

“One has one’s little pleasure for the day and one’s little pleasure for the night: but one has a regard for health. […] A little poison now and then: that makes for agreeable dreams. And much poison in the end, for an agreeable death.”

This need for comfort shows up as a need for harmony in interpersonal relationships:

“Becoming sick and harboring suspicion are sinful to them: one proceeds carefully. […] One still quarrels, but one is soon reconciled—else it might spoil the digestion.”

And it shows up socially in the form of egalitarianism and democratic ideals:

“No shepherd and one herd! Everybody wants the same, everybody is the same: whoever feels different goes voluntarily into a madhouse.

“‘Formerly, all the world was mad,’ say the most refined, and they blink.

To the Last Man this seems like Utopia; twice in Zarathustra’s speech they say

“We have invented happiness, and they blink”

This blinking in these quotes is repeated a number of times in this passage on the Last Man. It puts us in mind of some docile animal. Just what animal Nietzsche has in mind seems to be revealed from the reaction of the crowd, who, having dismissed Zarathustra’s message:

“jubilated and clucked with their tongues”

So it seems that what Nietzsche wants us to think of when it comes to the Last Man then is of a flock of chickens. This also fits with the imagery of the warmth:

“One still loves one’s neighbor and rubs against him, for one needs warmth.”

The impression Nietzsche leaves us with is that the Last Man is a docile domesticated animal — an idea reinforced by the phrase he uses about the soil in the passage we quoted earlier; when the soil has lost its richness it hasn’t simply become poor but “poor and domesticated”.

This theme of domestication is important then. It fits with Nietzsche’s disdain for the Herd which itself is connected with his idea of Slave Morality. Nietzsche doesn’t want a humanity of herd animals — of chickens or cows. To him these animals are prey animals. They are not the apex of life but the bottom feeders. They are the fodder which sustain the great birds of prey. They are necessary as a foundation for greatness but they are far from being the goal in themselves.

In The Gay Science Nietzsche writes that “Morality is the herd-instinct in the individual.” And in The Genealogy of Morals he contrasts lambs — the embodiments of Slave Morality — with birds of prey. To the lambs the birds of prey are simply evil. But the bird of prey suffers from no such moralistic qualms. Instead they reply:

“We have nothing against these good lambs; in fact, we love them; nothing tastes better than a tender lamb.”

So this predator and prey distinction then is another way of framing Nietzsche’s idea of the ideal Übermensch and the counter-ideal the Last Man. He sees an opportunity for humanity to soar but it requires leaving behind the herd or preying on the herd.

To the vast majority of us this isn’t the kind of ideal we want to embody in our lives. But there is still much to be learned from the idea of the Last Man and his antipode the Übermensch.

The Prophetic Truth of the Last Man?

Most of us go through life feeling too busy, too stressed, too put upon. We dream of retirement and of our day of rest. We dream of the day we can put down the cup and just take it easy. The idea of a life of comfort — where we work as much as we want to work and we don’t fall out with our neighbour and we have a little pleasure and an easy death — this is the kind of life we usually associate with utopia.

This life has even become possible with the technological evolutions of modern times. Indeed this is the exact promise that modern society dangles like a carrot in front of us. From Tim Ferriss’s insanely popular idea of the 4-Hour Workweek to all the products which are meant to make our lives easier like air conditioning, dishwashers and the million and one apps on our phones and our computers — there is a sprawling modern marketplace nurturing and milking this dream that Nietzsche calls the Last Man.

But there are many reasons to believe that this dream would in fact be a nightmare and would be the perfect fulfilment of Oscar Wilde’s pithy epigram that

In this world there are only two tragedies. One is not getting what one wants, and the other is getting it. The last is much the worst, the last is the real tragedy

In the century and a half since Zarathustra burst on the scene, Nietzsche’s insight into the nightmare of the Last Man has bubbled from its Zarathustran depths to the surface of cultural consciousness.

In his novel Brave New World Aldous Huxley paints the picture of a society where pain has ceased to exist, where negative emotions are washed away by the wonder-drug Soma, where life is comfortable and everybody is happy. Our knee-jerk reaction to this image is one of wonder and hope — this must be utopia. But the reality is anything but.

In the erasure of negative emotions something fundamental to the human experience is lost. There’s a scene in the book which cuts to the core of this something missing. The protagonist of Brave New World is a savage called John who was raised in a tribe outside the technological utopia. In this scene John is brought before Mustapha Mond — the Resident World Controller of Western Europe — for starting a riot as he attempted to stop the distribution of the wonder drug soma. Mond explains to John the workings of this utopian system and how it has made life comfortable and predictable.

‘But I don’t want comfort’ replies John

I want God, I want poetry, I want real danger, I want freedom, I want goodness. I want sin.’

‘In fact,’ said Mustapha Mond, ‘you’re claiming the right to be unhappy. Not to mention the right to grow old and ugly and impotent; the right to have syphilis and cancer, the right to have too little to eat; the right to be lousy; the right to live in constant apprehension of what may happen tomorrow; the right to catch typhoid; the right to be tortured by unspeakable pains of every kind.’ There was a long silence.

‘I claim them all,’ said the Savage at last.

Mustapha Mond shrugged his shoulders. ‘You’re welcome,’ he said.

This idea hasn’t just taken root in fiction but has become an emerging fact of psychology. In his book What Doesn’t Kill Us Professor Stephen Joseph unpacks the exploration in recent decades of Post-Traumatic Growth — whereby the experience of trauma can actually improve someone’s life rather than ruin it. There has also been a lot of work in the psychological study of mindsets which Kelly McGonigal’s book The Upside of Stress does a great job of exploring — bringing together as it does the studies which show that stress can make us happier healthier and more connected.

And on the flip side there is the stark reality of the mental health crisis. In his 2002 work Authentic Happiness, the father of Positive Psychology Martin Seligman noted that:

“Mounting over the last forty years in every wealthy country on the globe, there has been a startling increase in depression. Depression is now ten times as prevalent as it was in 1960, and it strikes at a much younger age. The mean age of a person’s first episode of depression forty years ago was 29.5, while today it is 14.5 years. This is a paradox, since every objective indicator of well-being—purchasing power, amount of education, availability of music, and nutrition—has been going north, while every indicator of subjective well-being has been going south. How is this epidemic to be explained?”

In the two decades since Seligman’s work was published the situation has gone from bad to much much worse.

So while we may not want to go full amoral bird of prey on our fellow humans, all of this suggests that there is at least something in Nietzsche’s warning about the Last Man which we should pay close attention to. We may want to learn a little mistrust for our comfort cravings.

The desire for the easy life speaks to a weariness with life. We are run ragged and worn down and we have lost our zest for the peaks. Instead of the challenge of the climb we crave the rest of the valley; instead of growth and truth we want comfort. But as we would learn if we were ever cursed with the tragedy of our wish being granted — comfort is its own form of hell.

Leave A Comment

― Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra

It is important in life that we have not just heroes but anti-heroes. We know who we are not just by what we are moving towards, but by what we are moving away from. In previous instalments we have talked a lot about Nietzsche’s ideal; we’ve looked at his life-affirming Dionysian ideal in a couple of articles and we looked at the stages of the development of his Übermensch in the Three Metamorphoses article.

But Nietzsche also has a counter-ideal and the name of this counter-ideal is “The Last Man”. This counter-ideal is articulated most thoroughly in the same place as his ideal — in the book for all and for none — Thus Spoke Zarathustra. There we find the Last Man introduced in sharp and eternal contrast with Nietzsche’s ideal — the Übermensch.

These two poles — the Übermensch and the Last Man are two responses to the death of God. In the ruins of the transcendent values, Nietzsche could only see two options — firstly the existential creation of our own values (which in Nietzsche takes on a Dionysian Darwinian tonality) or secondly, over against this path of health and challenge, there is the path of comfort, pleasure and the easy life i.e. the way of the Last Man.

This outlook of Nietzsche seems counterintuitive and alien at first sight — in no small part due to the strange Zarathustran package in which it comes wrapped. But fast forward to the 21st century and modern psychology — coming to terms as it is with the Mental Health crisis — suggests there may be something not just to Nietzsche’s warning about the Last Man but to his solution in the Übermensch.

The Last Man in Zarathustra

Feeling the sting of this disdain Zarathustra reflects to himself:

“There they stand,” he said to his heart; “there they laugh. They do not understand me; I am not the mouth for these ears. Must one smash their ears before they learn to listen with their eyes? Must one clatter like kettledrums and preachers of repentance? Or do they believe only the stammerer?

And it is at this point that he decides to try a different tactic. Instead of scolding them and pushing them to what they could be, i.e. the Übermensch, he goes the opposite way:

Let me then address their pride. Let me speak to them of what is most contemptible: but that is the last man.

And from here he embarks on his great warning of the trap of modern life. This warning dovetails well with his idea of the Herd and with Kierkegaard’s idea of the Crowd. This trap has emerged with the rise of modernity and the great mass production of human potential. The trap that Nietzsche is trying to warn us of is the temptation of an easy life.

With the death of God we stand at a crossroads. As we’ve talked about repeatedly on The Living Philosophy the death of God is both a dreadful curse but also a potentially abundant blessing. As well as a great danger there is a great potential. He writes:

“we philosophers and “free spirits .. feel, when we hear the news that “the old god is dead,” as if a new dawn shone on us; our heart overflows with gratitude, amazement, premonitions, expectation. At long last the horizon appears free to us again, even if it should not be bright; at long last our ships may venture out again, venture out to face any danger; all the daring of the lover of knowledge is permitted again; the sea, our sea, lies open again; perhaps there has never yet been such an ”open sea!””

But the flip side of this great potential is a great danger. In the language of the previous instalment with the death of God we have entered liminal space; of this liminality we can make either utopia or dystopia: Übermensch or Last Man.

As it stands the soil of our culture can still produce the towering canopies of human greatness but it will not always be this way. He writes:

“The time has come for man to set himself a goal. The time has come for man to plant the seed of his highest hope. His soil is still rich enough. But one day this soil will be poor and domesticated, and no tall tree will be able to grow in it. Alas, the time is coming when man will no longer shoot the arrow of his longing beyond man, and the string of his bow will have forgotten how to whir!”

Clearly Nietzsche’s preference is for the arrow that will go beyond man. But let’s take an in-depth look now at the alternative.

The Values of the Last Man

The unifying theme of the Last Man’s value system is comfort. Everything that he does is for the sake of having an easy life. The Last Man doesn’t want to overexert himself; he never strays far from the equilibrium of comfort.

“One no longer becomes poor or rich: both require too much exertion. Who still wants to rule? Who obey? Both require too much exertion.”

Entertainment is important but the Last Man is careful “less the entertainment be too harrowing”. This drive for comfort has even led to changes in where they live:

“They have left the regions where it was hard to live, for one needs warmth. One still loves one’s neighbor and rubs against him, for one needs warmth.”

Going with this there is the pacification of the Last Man with intoxicants and little helpers — within reason of course:

“One has one’s little pleasure for the day and one’s little pleasure for the night: but one has a regard for health. […] A little poison now and then: that makes for agreeable dreams. And much poison in the end, for an agreeable death.”

This need for comfort shows up as a need for harmony in interpersonal relationships:

“Becoming sick and harboring suspicion are sinful to them: one proceeds carefully. […] One still quarrels, but one is soon reconciled—else it might spoil the digestion.”

And it shows up socially in the form of egalitarianism and democratic ideals:

“No shepherd and one herd! Everybody wants the same, everybody is the same: whoever feels different goes voluntarily into a madhouse.

“‘Formerly, all the world was mad,’ say the most refined, and they blink.

To the Last Man this seems like Utopia; twice in Zarathustra’s speech they say

“We have invented happiness, and they blink”

This blinking in these quotes is repeated a number of times in this passage on the Last Man. It puts us in mind of some docile animal. Just what animal Nietzsche has in mind seems to be revealed from the reaction of the crowd, who, having dismissed Zarathustra’s message:

“jubilated and clucked with their tongues”

So it seems that what Nietzsche wants us to think of when it comes to the Last Man then is of a flock of chickens. This also fits with the imagery of the warmth:

“One still loves one’s neighbor and rubs against him, for one needs warmth.”

The impression Nietzsche leaves us with is that the Last Man is a docile domesticated animal — an idea reinforced by the phrase he uses about the soil in the passage we quoted earlier; when the soil has lost its richness it hasn’t simply become poor but “poor and domesticated”.

This theme of domestication is important then. It fits with Nietzsche’s disdain for the Herd which itself is connected with his idea of Slave Morality. Nietzsche doesn’t want a humanity of herd animals — of chickens or cows. To him these animals are prey animals. They are not the apex of life but the bottom feeders. They are the fodder which sustain the great birds of prey. They are necessary as a foundation for greatness but they are far from being the goal in themselves.

In The Gay Science Nietzsche writes that “Morality is the herd-instinct in the individual.” And in The Genealogy of Morals he contrasts lambs — the embodiments of Slave Morality — with birds of prey. To the lambs the birds of prey are simply evil. But the bird of prey suffers from no such moralistic qualms. Instead they reply:

“We have nothing against these good lambs; in fact, we love them; nothing tastes better than a tender lamb.”

So this predator and prey distinction then is another way of framing Nietzsche’s idea of the ideal Übermensch and the counter-ideal the Last Man. He sees an opportunity for humanity to soar but it requires leaving behind the herd or preying on the herd.

To the vast majority of us this isn’t the kind of ideal we want to embody in our lives. But there is still much to be learned from the idea of the Last Man and his antipode the Übermensch.

The Prophetic Truth of the Last Man?

Most of us go through life feeling too busy, too stressed, too put upon. We dream of retirement and of our day of rest. We dream of the day we can put down the cup and just take it easy. The idea of a life of comfort — where we work as much as we want to work and we don’t fall out with our neighbour and we have a little pleasure and an easy death — this is the kind of life we usually associate with utopia.

This life has even become possible with the technological evolutions of modern times. Indeed this is the exact promise that modern society dangles like a carrot in front of us. From Tim Ferriss’s insanely popular idea of the 4-Hour Workweek to all the products which are meant to make our lives easier like air conditioning, dishwashers and the million and one apps on our phones and our computers — there is a sprawling modern marketplace nurturing and milking this dream that Nietzsche calls the Last Man.

But there are many reasons to believe that this dream would in fact be a nightmare and would be the perfect fulfilment of Oscar Wilde’s pithy epigram that

In this world there are only two tragedies. One is not getting what one wants, and the other is getting it. The last is much the worst, the last is the real tragedy

In the century and a half since Zarathustra burst on the scene, Nietzsche’s insight into the nightmare of the Last Man has bubbled from its Zarathustran depths to the surface of cultural consciousness.

In his novel Brave New World Aldous Huxley paints the picture of a society where pain has ceased to exist, where negative emotions are washed away by the wonder-drug Soma, where life is comfortable and everybody is happy. Our knee-jerk reaction to this image is one of wonder and hope — this must be utopia. But the reality is anything but.

In the erasure of negative emotions something fundamental to the human experience is lost. There’s a scene in the book which cuts to the core of this something missing. The protagonist of Brave New World is a savage called John who was raised in a tribe outside the technological utopia. In this scene John is brought before Mustapha Mond — the Resident World Controller of Western Europe — for starting a riot as he attempted to stop the distribution of the wonder drug soma. Mond explains to John the workings of this utopian system and how it has made life comfortable and predictable.

‘But I don’t want comfort’ replies John

I want God, I want poetry, I want real danger, I want freedom, I want goodness. I want sin.’

‘In fact,’ said Mustapha Mond, ‘you’re claiming the right to be unhappy. Not to mention the right to grow old and ugly and impotent; the right to have syphilis and cancer, the right to have too little to eat; the right to be lousy; the right to live in constant apprehension of what may happen tomorrow; the right to catch typhoid; the right to be tortured by unspeakable pains of every kind.’ There was a long silence.

‘I claim them all,’ said the Savage at last.

Mustapha Mond shrugged his shoulders. ‘You’re welcome,’ he said.

This idea hasn’t just taken root in fiction but has become an emerging fact of psychology. In his book What Doesn’t Kill Us Professor Stephen Joseph unpacks the exploration in recent decades of Post-Traumatic Growth — whereby the experience of trauma can actually improve someone’s life rather than ruin it. There has also been a lot of work in the psychological study of mindsets which Kelly McGonigal’s book The Upside of Stress does a great job of exploring — bringing together as it does the studies which show that stress can make us happier healthier and more connected.

And on the flip side there is the stark reality of the mental health crisis. In his 2002 work Authentic Happiness, the father of Positive Psychology Martin Seligman noted that:

“Mounting over the last forty years in every wealthy country on the globe, there has been a startling increase in depression. Depression is now ten times as prevalent as it was in 1960, and it strikes at a much younger age. The mean age of a person’s first episode of depression forty years ago was 29.5, while today it is 14.5 years. This is a paradox, since every objective indicator of well-being—purchasing power, amount of education, availability of music, and nutrition—has been going north, while every indicator of subjective well-being has been going south. How is this epidemic to be explained?”

In the two decades since Seligman’s work was published the situation has gone from bad to much much worse.

So while we may not want to go full amoral bird of prey on our fellow humans, all of this suggests that there is at least something in Nietzsche’s warning about the Last Man which we should pay close attention to. We may want to learn a little mistrust for our comfort cravings.

The desire for the easy life speaks to a weariness with life. We are run ragged and worn down and we have lost our zest for the peaks. Instead of the challenge of the climb we crave the rest of the valley; instead of growth and truth we want comfort. But as we would learn if we were ever cursed with the tragedy of our wish being granted — comfort is its own form of hell.