Later in the article, I’ll talk a little bit about why I’ve started looking at political philosophy and where it fits in with the rest of the publication but for now let’s talk about the term Radical.

Radical comes from the Latin word “radix” meaning “root” which is very appropriate because political radicals are those who believe that there is something fundamentally wrong with the status quo — the problem goes to its very roots and it’s from there that change needs to be created.

Radicalism has usually been associated with the Far Left. In fact according to Fascist historian Kevin Passmore, Marxist attempts at understanding Fascism often failed because these historians were blind to its Radicalism because in their eyes only Socialism could be radical. There’s something revealing in this fact. — when we think about those who want to change the system we usually do think of the left. But it’s this sort of looseness with terminology — where we lazily assign it to a particular group and then forget about its meaning — that makes these terms useless. They become tags we attach to certain groups — tribal markers — rather than insightful terms.

But radical is a very important term for understanding today’s political landscape. I can’t think of any other term which captures so neatly the distressing spiral of American politics than the term radical.

The Two Faces of Radicalism

The first thing to understand about Radicalism is that it has a negative and a positive side.

On the negating side, Radicals are anti-establishment. They believe the current system is broken. The two big enemies shared by radicals of all stripes are bureaucracy and mainstream politicians. Radicals believe that the system is rotten to the core and if we want to build a better world we need to uproot this old system and start anew.

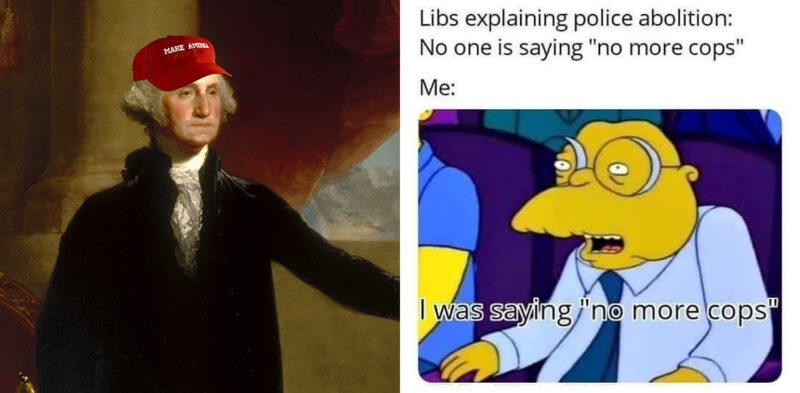

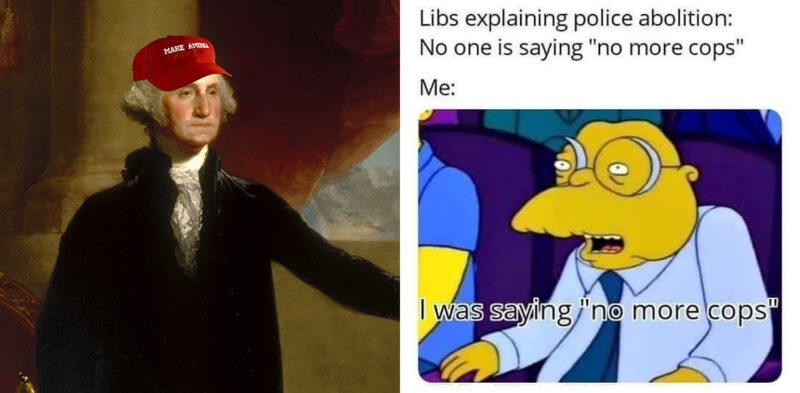

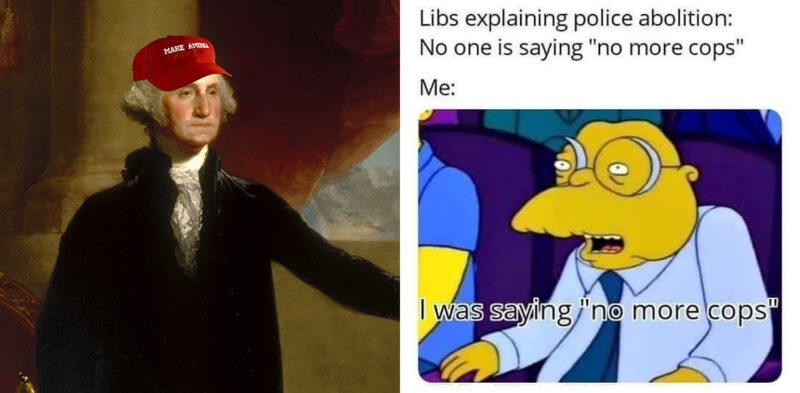

Think about Trump’s motto “drain the swamp” or the Progressive-Left’s movement to abolish the police. Though they are coming from opposite sides of the political spectrum, the Republican base and the far-Left share a hatred for the system as it is today. They think the system is beyond saving and so we need to start again.

Complementing this negative side Radicals have a positive vision of how things should be. The positive vision of the far-right, whether that’s Trump or the mid-20th century Fascists, lies in the past. Mussolini wanted to get back to the Ancient Romans and Trump wants to make America Great Again. Their positive vision is a return to a glorious former state.

The left-wing radicals however have dreams of a never-before-seen utopia. Marx was not a man that wanted to go back; he was a big fan of capitalist modernity. As a Hegelian developmental thinker, Marx believed that this capitalist modernity would inevitably evolve into a Communist utopia and so he celebrated the success of Capitalism across the world as the distant dawn of Communism. First the workers would seize the means of production and the state and eventually this state would wither away into an Anarchist paradise where each would give according to their ability and receive according to their need.

Anarchists have a similar vision only it’s not usually seen in Hegelian terms as an inevitability of history. They also aren’t too mad about the middle phases of domination (which while novel are still alas domination). The 20th century has provided a number of examples of where this middle phase can go a bit awry.

What these left-wing radicals share is a vision of a better future. It is this future we are working so hard to progress towards. Like the right-wing radicals they see a better future but unlike the right they see this future as something we progress towards rather than return to. Both are looking to cut this system up at the roots but the roots they are trying to plant in place of the status quo are very different.

Mobilisation

This anti-establishment worldview brings about other shared traits between left-wing and right-wing radicals.

One of these is the idea of mobilisation (another one of those political terms worthy of contemplation; put simply — having a highly engaged activist support base). There’s a lot of common sense to this connection. If you think that the system is fundamentally flawed and in need of change then it makes sense that if you want to have any hope of changing it you are going to need to be organised.

This is something we are very familiar with in left-wing politics. The Black Lives Matter protests and the Global Climate Strike are part of a long lineage of radical grassroots mobilisation on the left-wing end of spectrum.

Right-wing radicalism has a different flavour. In the interwar years of the 20th century the Blackshirts in Italy and the Brownshirts in Germany were paramilitary groups that made the rise of Fascism in Europe possible. The past few decades have seen the rise of paramilitary groups in the US. There is a lot of support for Trump among these groups and there have been clashes between these militia and left-wing protesters in the last few years. Many members of these groups were involved in the storming of the US Capitol building on January 6th 2021.

This militia mobilisation isn’t just a part of the right-wing but groups like the Black Panthers and the US Organisation were radical leftist paramilitary groups in the 60s and 70s and other leftist militias played a key part of Communist revolutions across the world in the 20th century. And over the past three years we have seen a sort of radical leftist militia in Antifa clash in the streets against the radical right militia groups like the Proud Boys and Patriot Prayer.

The bottom line is when the establishment isn’t on your side, then you have to organise your own countermovement to stand against the highly organised totalising system. This applies to both left- and right-wing radicals.

Closing Remarks

I’ve been reflecting recently on what the defining arc of the publication is. After two and a half years the direction of The Living Philosophy is still emerging for me. I’m beginning to see some dots clicking together but in a way this publication is an exercise in individuation. In trying to understand the world we are living in and trying to empathise with the various points of view that are clashing in the world today I’ve ended up writing articles in a lot of different territories from Nihilism and Existentialism to Veganism, Conspiracy Theories and Metamodernism.

I’m coming to realise that the topics that draw me back again and again orbit the meta-crisis — the mega-crisis composed of many sub-crises — that’s going on in our culture today. And two crises in particular keep coming back to me: the meaning crisis of Nihilism and the sensemaking crisis of the Culture Wars. Recently I’ve been discovering that these issues are not separate.

And I’ve come to realise that you can’t talk about the Culture Wars without talking about political philosophy. And so in trying to figure out these crises and how they interact with each other I’ve realised that we have to dabble in political philosophy and so this instalment marks the beginning of this dabbling.

Over the next few months we’re going to have at least one more terminological article on the term Reactionary but I also want to explore the limitations of the left/right spectrum, what Fascism is and what Marx was all about. I’m sure there’ll be more beyond these but these are the initial peaks that are jumping out at me so I thought I’d give a brief introduction to this journey with these closing remarks at the start of this series just so you all know what’s going on. Politics isn’t going to become the centre of the publication by any means — I’m also working on a series centred around the anthropological idea of Liminality and a few other things but it’s just going to be a part of The Living Philosophy mix going forward.

3 Comments

Leave A Comment

Later in the article, I’ll talk a little bit about why I’ve started looking at political philosophy and where it fits in with the rest of the publication but for now let’s talk about the term Radical.

Radical comes from the Latin word “radix” meaning “root” which is very appropriate because political radicals are those who believe that there is something fundamentally wrong with the status quo — the problem goes to its very roots and it’s from there that change needs to be created.

Radicalism has usually been associated with the Far Left. In fact according to Fascist historian Kevin Passmore, Marxist attempts at understanding Fascism often failed because these historians were blind to its Radicalism because in their eyes only Socialism could be radical. There’s something revealing in this fact. — when we think about those who want to change the system we usually do think of the left. But it’s this sort of looseness with terminology — where we lazily assign it to a particular group and then forget about its meaning — that makes these terms useless. They become tags we attach to certain groups — tribal markers — rather than insightful terms.

But radical is a very important term for understanding today’s political landscape. I can’t think of any other term which captures so neatly the distressing spiral of American politics than the term radical.

The Two Faces of Radicalism

The first thing to understand about Radicalism is that it has a negative and a positive side.

On the negating side, Radicals are anti-establishment. They believe the current system is broken. The two big enemies shared by radicals of all stripes are bureaucracy and mainstream politicians. Radicals believe that the system is rotten to the core and if we want to build a better world we need to uproot this old system and start anew.

Think about Trump’s motto “drain the swamp” or the Progressive-Left’s movement to abolish the police. Though they are coming from opposite sides of the political spectrum, the Republican base and the far-Left share a hatred for the system as it is today. They think the system is beyond saving and so we need to start again.

Complementing this negative side Radicals have a positive vision of how things should be. The positive vision of the far-right, whether that’s Trump or the mid-20th century Fascists, lies in the past. Mussolini wanted to get back to the Ancient Romans and Trump wants to make America Great Again. Their positive vision is a return to a glorious former state.

The left-wing radicals however have dreams of a never-before-seen utopia. Marx was not a man that wanted to go back; he was a big fan of capitalist modernity. As a Hegelian developmental thinker, Marx believed that this capitalist modernity would inevitably evolve into a Communist utopia and so he celebrated the success of Capitalism across the world as the distant dawn of Communism. First the workers would seize the means of production and the state and eventually this state would wither away into an Anarchist paradise where each would give according to their ability and receive according to their need.

Anarchists have a similar vision only it’s not usually seen in Hegelian terms as an inevitability of history. They also aren’t too mad about the middle phases of domination (which while novel are still alas domination). The 20th century has provided a number of examples of where this middle phase can go a bit awry.

What these left-wing radicals share is a vision of a better future. It is this future we are working so hard to progress towards. Like the right-wing radicals they see a better future but unlike the right they see this future as something we progress towards rather than return to. Both are looking to cut this system up at the roots but the roots they are trying to plant in place of the status quo are very different.

Mobilisation

This anti-establishment worldview brings about other shared traits between left-wing and right-wing radicals.

One of these is the idea of mobilisation (another one of those political terms worthy of contemplation; put simply — having a highly engaged activist support base). There’s a lot of common sense to this connection. If you think that the system is fundamentally flawed and in need of change then it makes sense that if you want to have any hope of changing it you are going to need to be organised.

This is something we are very familiar with in left-wing politics. The Black Lives Matter protests and the Global Climate Strike are part of a long lineage of radical grassroots mobilisation on the left-wing end of spectrum.

Right-wing radicalism has a different flavour. In the interwar years of the 20th century the Blackshirts in Italy and the Brownshirts in Germany were paramilitary groups that made the rise of Fascism in Europe possible. The past few decades have seen the rise of paramilitary groups in the US. There is a lot of support for Trump among these groups and there have been clashes between these militia and left-wing protesters in the last few years. Many members of these groups were involved in the storming of the US Capitol building on January 6th 2021.

This militia mobilisation isn’t just a part of the right-wing but groups like the Black Panthers and the US Organisation were radical leftist paramilitary groups in the 60s and 70s and other leftist militias played a key part of Communist revolutions across the world in the 20th century. And over the past three years we have seen a sort of radical leftist militia in Antifa clash in the streets against the radical right militia groups like the Proud Boys and Patriot Prayer.

The bottom line is when the establishment isn’t on your side, then you have to organise your own countermovement to stand against the highly organised totalising system. This applies to both left- and right-wing radicals.

Closing Remarks

I’ve been reflecting recently on what the defining arc of the publication is. After two and a half years the direction of The Living Philosophy is still emerging for me. I’m beginning to see some dots clicking together but in a way this publication is an exercise in individuation. In trying to understand the world we are living in and trying to empathise with the various points of view that are clashing in the world today I’ve ended up writing articles in a lot of different territories from Nihilism and Existentialism to Veganism, Conspiracy Theories and Metamodernism.

I’m coming to realise that the topics that draw me back again and again orbit the meta-crisis — the mega-crisis composed of many sub-crises — that’s going on in our culture today. And two crises in particular keep coming back to me: the meaning crisis of Nihilism and the sensemaking crisis of the Culture Wars. Recently I’ve been discovering that these issues are not separate.

And I’ve come to realise that you can’t talk about the Culture Wars without talking about political philosophy. And so in trying to figure out these crises and how they interact with each other I’ve realised that we have to dabble in political philosophy and so this instalment marks the beginning of this dabbling.

Over the next few months we’re going to have at least one more terminological article on the term Reactionary but I also want to explore the limitations of the left/right spectrum, what Fascism is and what Marx was all about. I’m sure there’ll be more beyond these but these are the initial peaks that are jumping out at me so I thought I’d give a brief introduction to this journey with these closing remarks at the start of this series just so you all know what’s going on. Politics isn’t going to become the centre of the publication by any means — I’m also working on a series centred around the anthropological idea of Liminality and a few other things but it’s just going to be a part of The Living Philosophy mix going forward.

3 Comments

-

[…] If you’d asked me a few months ago what the term reactionary meant I could have told you that it was associated with the right-wing and that it was usually used as an insult rather than a self-identifier but beyond that I couldn’t have told you what it actually meant. It’s one of those political terms I’ve heard floating around for years but never paid direct attention to. There seem to be quite a few of these in politics as we saw in the last instalment with the term Radical. […]

-

this article is informative and juicy for me as a reader to read. can you explained more about political philosophy and i’m the innocent person want a learn about political philosophy to improve my understand as a person who doesn’t understand politics.

-

[…] peculiar fact is not unique to 21st-century America but has a long history in radical […]

Leave A Comment

Later in the article, I’ll talk a little bit about why I’ve started looking at political philosophy and where it fits in with the rest of the publication but for now let’s talk about the term Radical.

Radical comes from the Latin word “radix” meaning “root” which is very appropriate because political radicals are those who believe that there is something fundamentally wrong with the status quo — the problem goes to its very roots and it’s from there that change needs to be created.

Radicalism has usually been associated with the Far Left. In fact according to Fascist historian Kevin Passmore, Marxist attempts at understanding Fascism often failed because these historians were blind to its Radicalism because in their eyes only Socialism could be radical. There’s something revealing in this fact. — when we think about those who want to change the system we usually do think of the left. But it’s this sort of looseness with terminology — where we lazily assign it to a particular group and then forget about its meaning — that makes these terms useless. They become tags we attach to certain groups — tribal markers — rather than insightful terms.

But radical is a very important term for understanding today’s political landscape. I can’t think of any other term which captures so neatly the distressing spiral of American politics than the term radical.

The Two Faces of Radicalism

The first thing to understand about Radicalism is that it has a negative and a positive side.

On the negating side, Radicals are anti-establishment. They believe the current system is broken. The two big enemies shared by radicals of all stripes are bureaucracy and mainstream politicians. Radicals believe that the system is rotten to the core and if we want to build a better world we need to uproot this old system and start anew.

Think about Trump’s motto “drain the swamp” or the Progressive-Left’s movement to abolish the police. Though they are coming from opposite sides of the political spectrum, the Republican base and the far-Left share a hatred for the system as it is today. They think the system is beyond saving and so we need to start again.

Complementing this negative side Radicals have a positive vision of how things should be. The positive vision of the far-right, whether that’s Trump or the mid-20th century Fascists, lies in the past. Mussolini wanted to get back to the Ancient Romans and Trump wants to make America Great Again. Their positive vision is a return to a glorious former state.

The left-wing radicals however have dreams of a never-before-seen utopia. Marx was not a man that wanted to go back; he was a big fan of capitalist modernity. As a Hegelian developmental thinker, Marx believed that this capitalist modernity would inevitably evolve into a Communist utopia and so he celebrated the success of Capitalism across the world as the distant dawn of Communism. First the workers would seize the means of production and the state and eventually this state would wither away into an Anarchist paradise where each would give according to their ability and receive according to their need.

Anarchists have a similar vision only it’s not usually seen in Hegelian terms as an inevitability of history. They also aren’t too mad about the middle phases of domination (which while novel are still alas domination). The 20th century has provided a number of examples of where this middle phase can go a bit awry.

What these left-wing radicals share is a vision of a better future. It is this future we are working so hard to progress towards. Like the right-wing radicals they see a better future but unlike the right they see this future as something we progress towards rather than return to. Both are looking to cut this system up at the roots but the roots they are trying to plant in place of the status quo are very different.

Mobilisation

This anti-establishment worldview brings about other shared traits between left-wing and right-wing radicals.

One of these is the idea of mobilisation (another one of those political terms worthy of contemplation; put simply — having a highly engaged activist support base). There’s a lot of common sense to this connection. If you think that the system is fundamentally flawed and in need of change then it makes sense that if you want to have any hope of changing it you are going to need to be organised.

This is something we are very familiar with in left-wing politics. The Black Lives Matter protests and the Global Climate Strike are part of a long lineage of radical grassroots mobilisation on the left-wing end of spectrum.

Right-wing radicalism has a different flavour. In the interwar years of the 20th century the Blackshirts in Italy and the Brownshirts in Germany were paramilitary groups that made the rise of Fascism in Europe possible. The past few decades have seen the rise of paramilitary groups in the US. There is a lot of support for Trump among these groups and there have been clashes between these militia and left-wing protesters in the last few years. Many members of these groups were involved in the storming of the US Capitol building on January 6th 2021.

This militia mobilisation isn’t just a part of the right-wing but groups like the Black Panthers and the US Organisation were radical leftist paramilitary groups in the 60s and 70s and other leftist militias played a key part of Communist revolutions across the world in the 20th century. And over the past three years we have seen a sort of radical leftist militia in Antifa clash in the streets against the radical right militia groups like the Proud Boys and Patriot Prayer.

The bottom line is when the establishment isn’t on your side, then you have to organise your own countermovement to stand against the highly organised totalising system. This applies to both left- and right-wing radicals.

Closing Remarks

I’ve been reflecting recently on what the defining arc of the publication is. After two and a half years the direction of The Living Philosophy is still emerging for me. I’m beginning to see some dots clicking together but in a way this publication is an exercise in individuation. In trying to understand the world we are living in and trying to empathise with the various points of view that are clashing in the world today I’ve ended up writing articles in a lot of different territories from Nihilism and Existentialism to Veganism, Conspiracy Theories and Metamodernism.

I’m coming to realise that the topics that draw me back again and again orbit the meta-crisis — the mega-crisis composed of many sub-crises — that’s going on in our culture today. And two crises in particular keep coming back to me: the meaning crisis of Nihilism and the sensemaking crisis of the Culture Wars. Recently I’ve been discovering that these issues are not separate.

And I’ve come to realise that you can’t talk about the Culture Wars without talking about political philosophy. And so in trying to figure out these crises and how they interact with each other I’ve realised that we have to dabble in political philosophy and so this instalment marks the beginning of this dabbling.

Over the next few months we’re going to have at least one more terminological article on the term Reactionary but I also want to explore the limitations of the left/right spectrum, what Fascism is and what Marx was all about. I’m sure there’ll be more beyond these but these are the initial peaks that are jumping out at me so I thought I’d give a brief introduction to this journey with these closing remarks at the start of this series just so you all know what’s going on. Politics isn’t going to become the centre of the publication by any means — I’m also working on a series centred around the anthropological idea of Liminality and a few other things but it’s just going to be a part of The Living Philosophy mix going forward.

3 Comments

-

[…] If you’d asked me a few months ago what the term reactionary meant I could have told you that it was associated with the right-wing and that it was usually used as an insult rather than a self-identifier but beyond that I couldn’t have told you what it actually meant. It’s one of those political terms I’ve heard floating around for years but never paid direct attention to. There seem to be quite a few of these in politics as we saw in the last instalment with the term Radical. […]

-

this article is informative and juicy for me as a reader to read. can you explained more about political philosophy and i’m the innocent person want a learn about political philosophy to improve my understand as a person who doesn’t understand politics.

-

[…] peculiar fact is not unique to 21st-century America but has a long history in radical […]

[…] If you’d asked me a few months ago what the term reactionary meant I could have told you that it was associated with the right-wing and that it was usually used as an insult rather than a self-identifier but beyond that I couldn’t have told you what it actually meant. It’s one of those political terms I’ve heard floating around for years but never paid direct attention to. There seem to be quite a few of these in politics as we saw in the last instalment with the term Radical. […]

this article is informative and juicy for me as a reader to read. can you explained more about political philosophy and i’m the innocent person want a learn about political philosophy to improve my understand as a person who doesn’t understand politics.

[…] peculiar fact is not unique to 21st-century America but has a long history in radical […]