Emerson’s essay Self-Reliance was one of the first pieces of philosophy I ever read. And it was one of those fortuitous encounters that shaped my life in many ways. I first read it as a teenager at a crossroads in life; it was a time when big decisions about the future had to be made and Self-Reliance gave me the self-belief to dream more audaciously than my timid heart was temperamentally accustomed to.

It’s been a good few years since I sat down and went through the whole thing and so when I sat down recently and did just that I found myself blown away once again by this rhetorical masterpiece. If you’ve never read it I would recommend sitting down for five minutes and reading the first few paragraphs (link to full essay).

It’s an absolutely sublime bit of work and reading it today I can see how much it has coloured my worldview and shaped who I am. I don’t think of it that often anymore (except when certain lines from it bubble up to the front of my consciousness now and again) but, just as your average modern European doesn’t give much thought to the Ancient Greeks, there’s an archaeology of the soul whereby even things forgotten continue to shape us whether we are aware of them or not.

Reading it has yet again filled me with inspiration. Everything that I mean and everything that I feel with the words living philosophy is embodied in this essay. I can see foreshadowings of what Emerson would call The Living Philosophy’s “long foreground” in this essay. The inspiration was no doubt helped along this time by the more recently acquired knowledge that Emerson’s work was a pivotal influence on Nietzsche.

Obviously this time I had another intention when reading it as well and that was with the eye of a communicator. I was reading it with an eye to its essence with an eye to what it is about, how it unfolds, and why it is so amazing. And being quite a floral rhetorical piece rather than an argument made up of a series of propositions I actually had a bit of difficulty unearthing the structure.

I could go down a whole rabbit hole on this — it’s something I’ve thought about quite a lot recently with books and with all reading — the not so obvious art of how to read a book well. This time I thought I’d play with a lens that I picked up from my recent dabblings in Continental Philosophy and that is the idea of binary oppositions — essentially pairs of opposites — something I imagine we’ll be exploring in much more depth when we start talking about Derrida.

So I began looking for the binary oppositions in Emerson’s piece and I can only recommend this approach highly enough because it unlocked the whole essay for me. I could now see the things that Emerson valued both in their hallowed haloed form and in their shadow vice form. And so I thought that this might make an interesting way of approaching this essay of essays: through the medium of the binary oppositions that show what Emerson truly values. So this article is going to be an exploration of Emerson’s work through the lens of these binaries: greatness vs. meanness; the aboriginal self vs society; the dead past vs. the eternal present; and self-reliance vs. conformity.

Greatness vs. Meanness

A good binary opposition to start with that really sets the scene is Emerson’s dichotomy between greatness and meanness — or to use Nietzsche’s preferred term mediocrity. What the “great” value of Self-Reliance is seeking to bring about is the state of greatness. Emerson is concerned with the great people of history and he is encouraging us loyal readers to rise above the inertia of mediocrity and to attain the levels of human greatness.

The kind of people he has in mind aren’t just sages but statesmen, generals scientists and mystics. There’s Jesus and Socrates, Napoleon and Scipio, Pythagoras, Newton, Emmanuel Swedenborg, Diogenes, Zoroaster Washington, and Caesar.

These are all great individuals who left an indelible mark on the world. It wasn’t through the force of pen or sword that they did so but through the force of character. They were all self-reliant individuals who broke free from the gravity of society and were true to their inner genius. Emerson calls us to rise to the heights that are possible of humanity and to count ourselves among the greats rather than succumbing to the inertia of mediocrity.

Self vs Society

The second key binary opposition is between society and what Emerson calls the aboriginal Self.

This aboriginal self is the source of all genius, it is the source of virtue and of life. This source Emerson tells us can be called Spontaneity, Instinct or Intuition (after which “all later teachings are tuitions”).

So self-reliance then isn’t a reliance on a simple ego it’s not about becoming selfish. On the contrary Emerson tells us that the key trait of self-reliance is obedience and faith. It is following the course of this inner wisdom. He writes that he “Who has more obedience than I masters me, though he should not raise his finger.”

This following the self then isn’t about forcing our will on the world but it is to “allow a passage to its beams.” For those who have studied Jung, this immediately brings to mind his conception of the Self – the centre of consciousness around which our ego is to orbit and to be obedient to.

Over against this noble oversoul is Society. Society is Emerson’s big demon in Self-Reliance. It’s everything that the aboriginal self is not. For all the lightness of the aboriginal self, society is the darkening cheapening force in human life.

Society everywhere is in conspiracy against the manhood of every one of its members. Society is a joint-stock company, in which the members agree, for the better securing of his bread to each shareholder, to surrender the liberty and culture of the eater.

Under the influence of society, we tow the line of the shoulds and should nots. We become blinker-eyed members of “communities of opinion”. Society tames the genius of individuals who step out of line with what the mainstream says and greet the genius with sour faces but Emerson tells us “the sour faces of the multitude, like their sweet faces, have no deep cause, but are put on and off as the wind blows and a newspaper directs.”

Under the influence of society all of our virtues are impotent. The virtues of those allied to society are “penances” — it’s not something that bubbles up from within, it’s not an expression of this soul or spirit but something that is extorted, something done out of guilt.

This capitulation to society’s demands “scatters your force” and we are left muddied shadows of ourselves.

The Dead Past and the Eternal Present

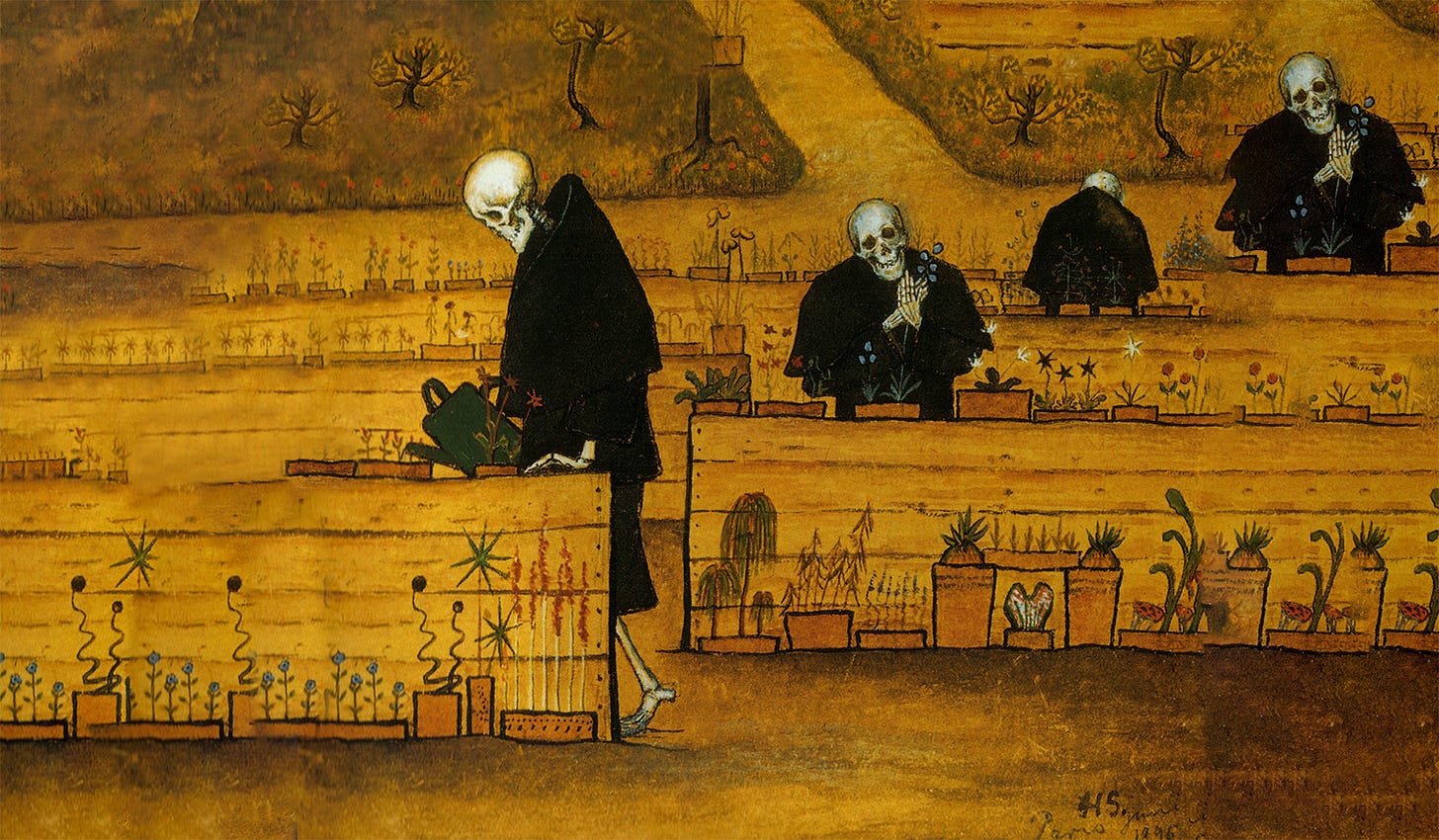

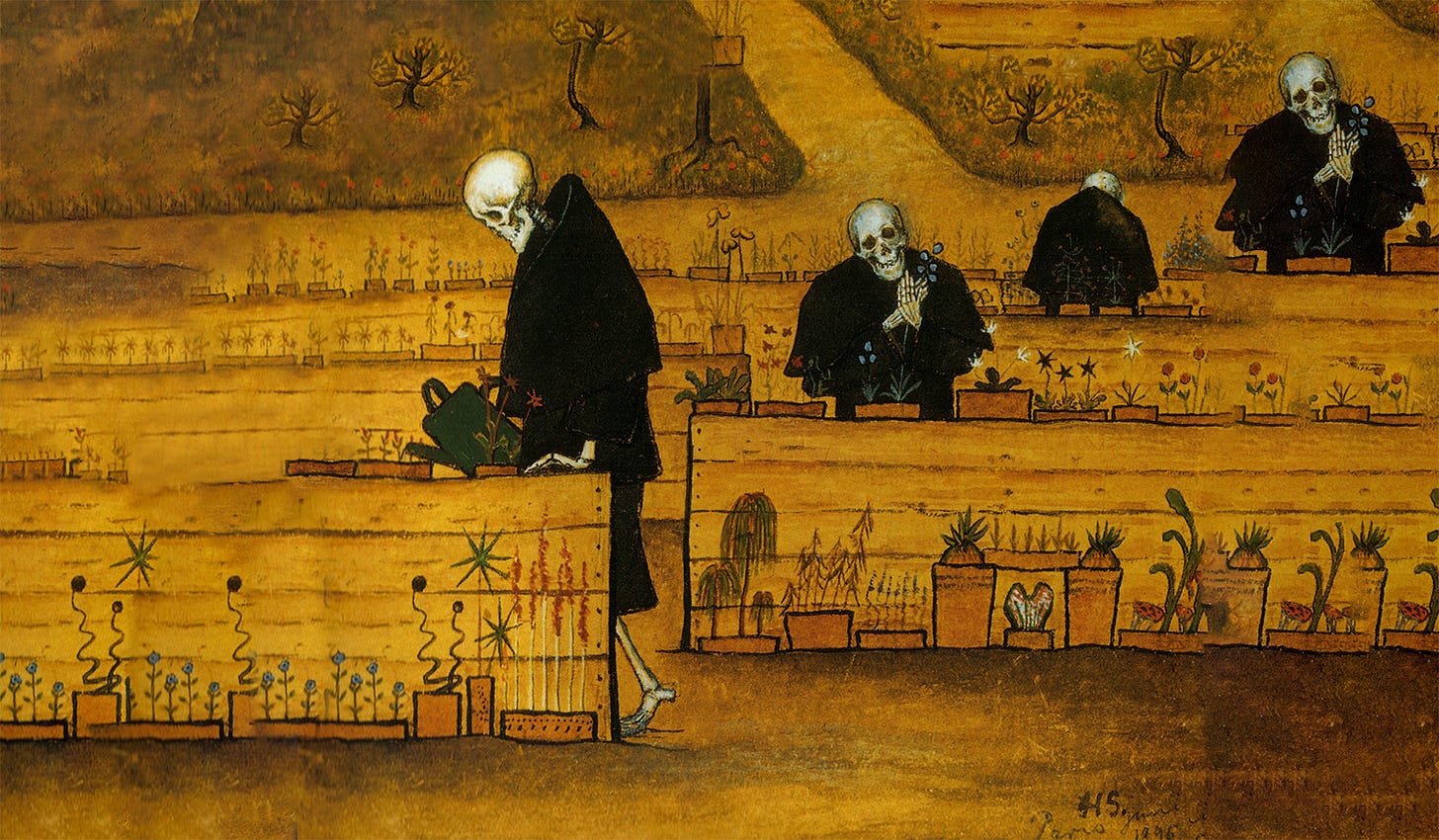

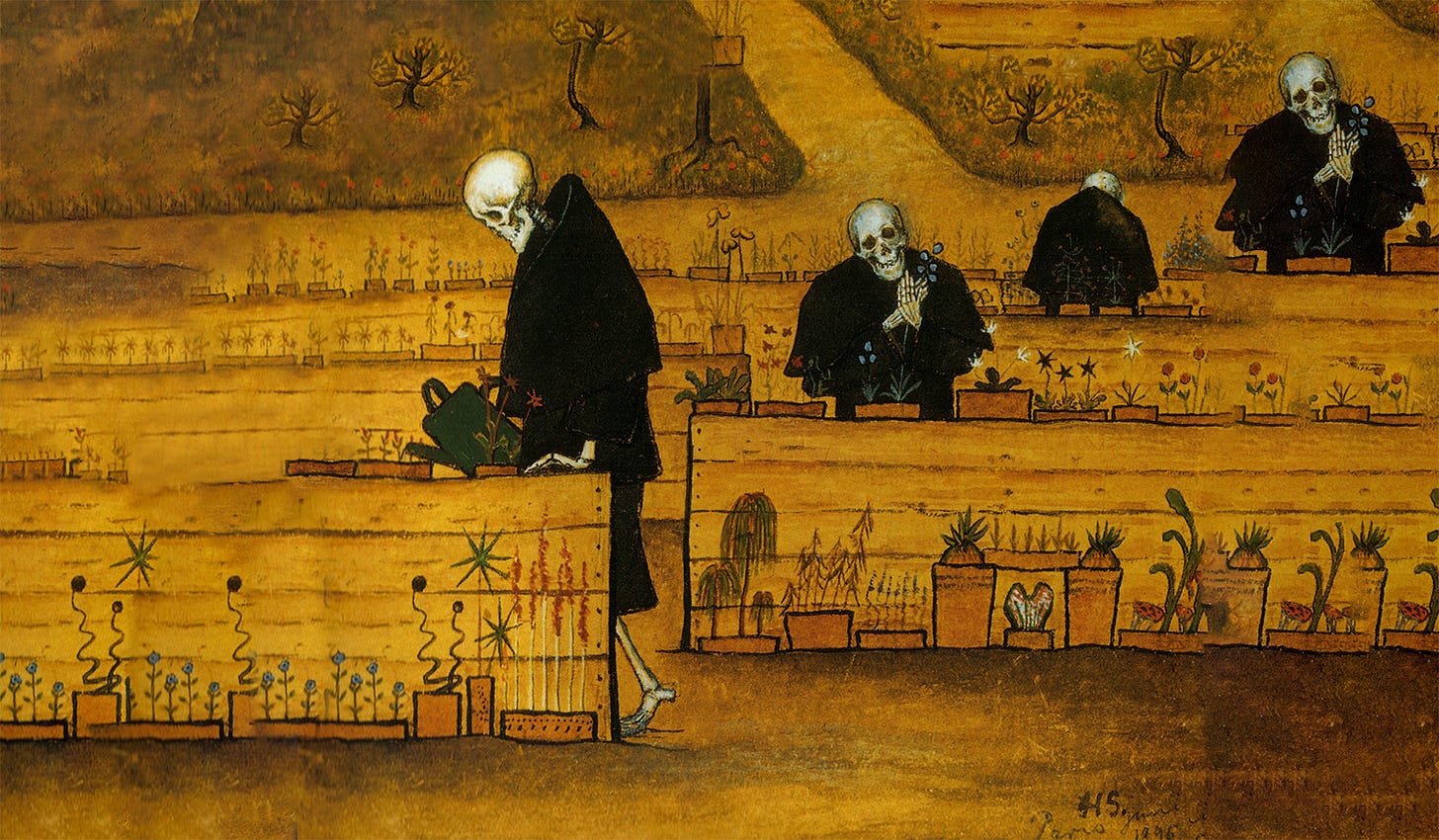

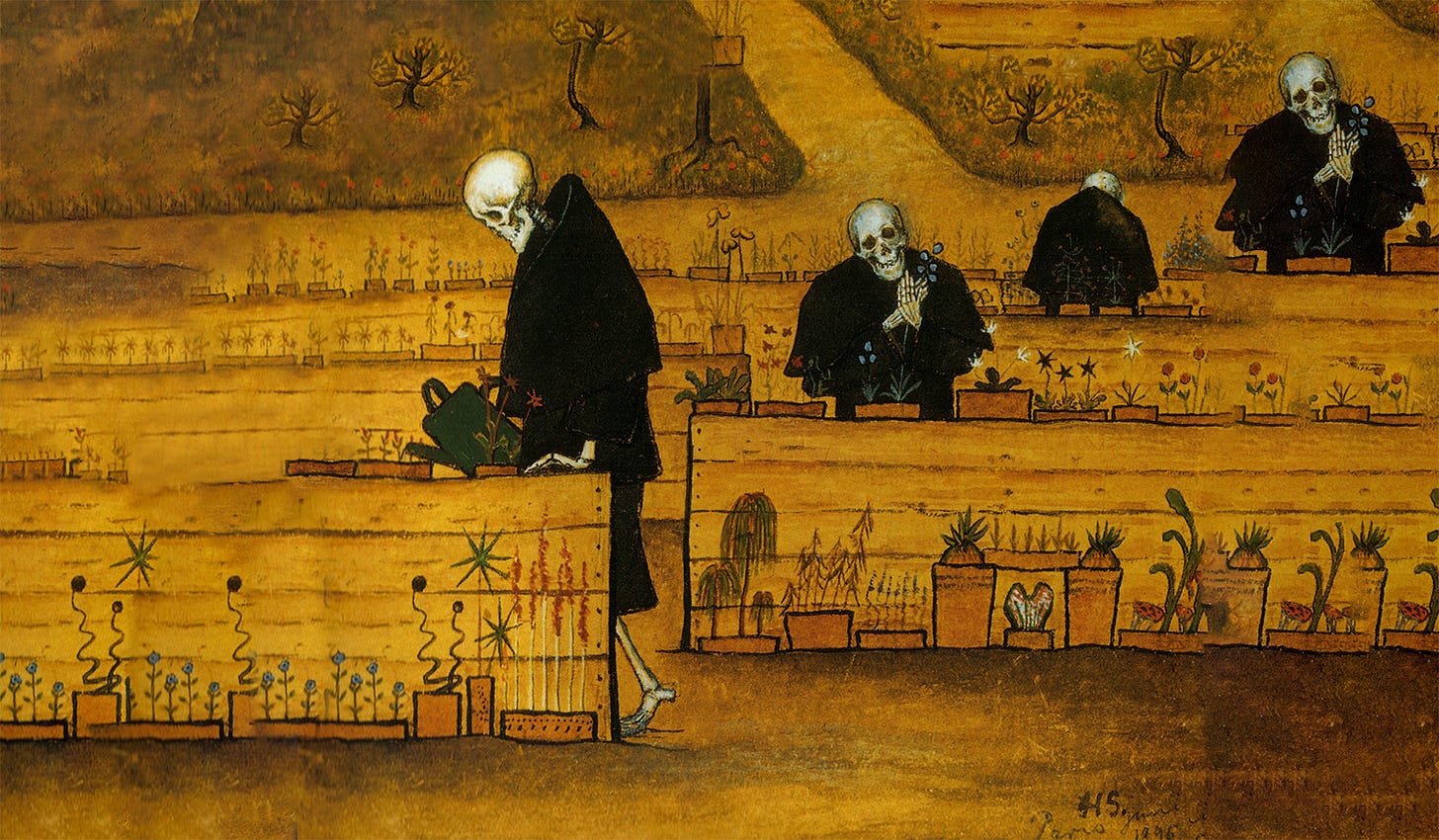

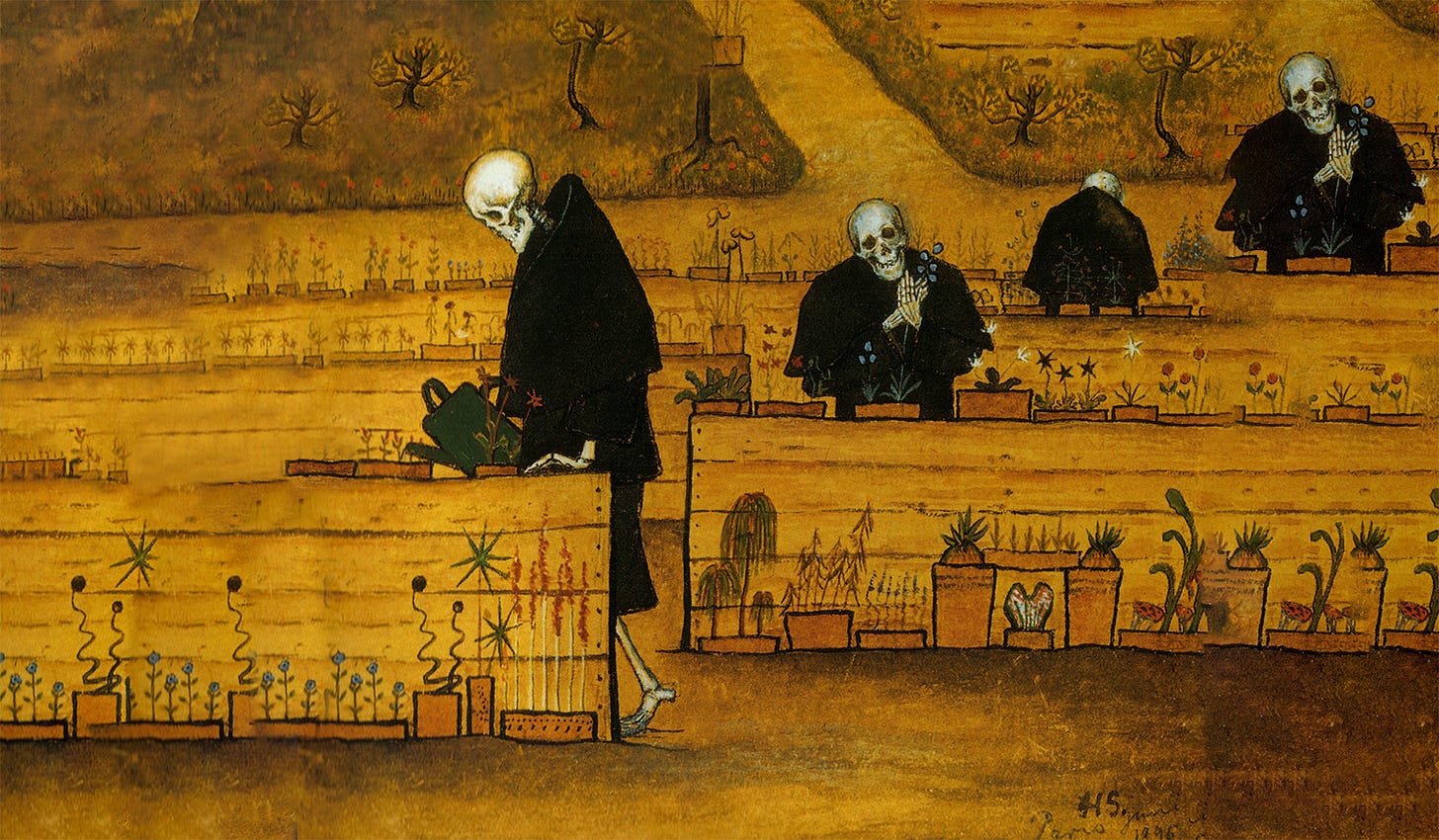

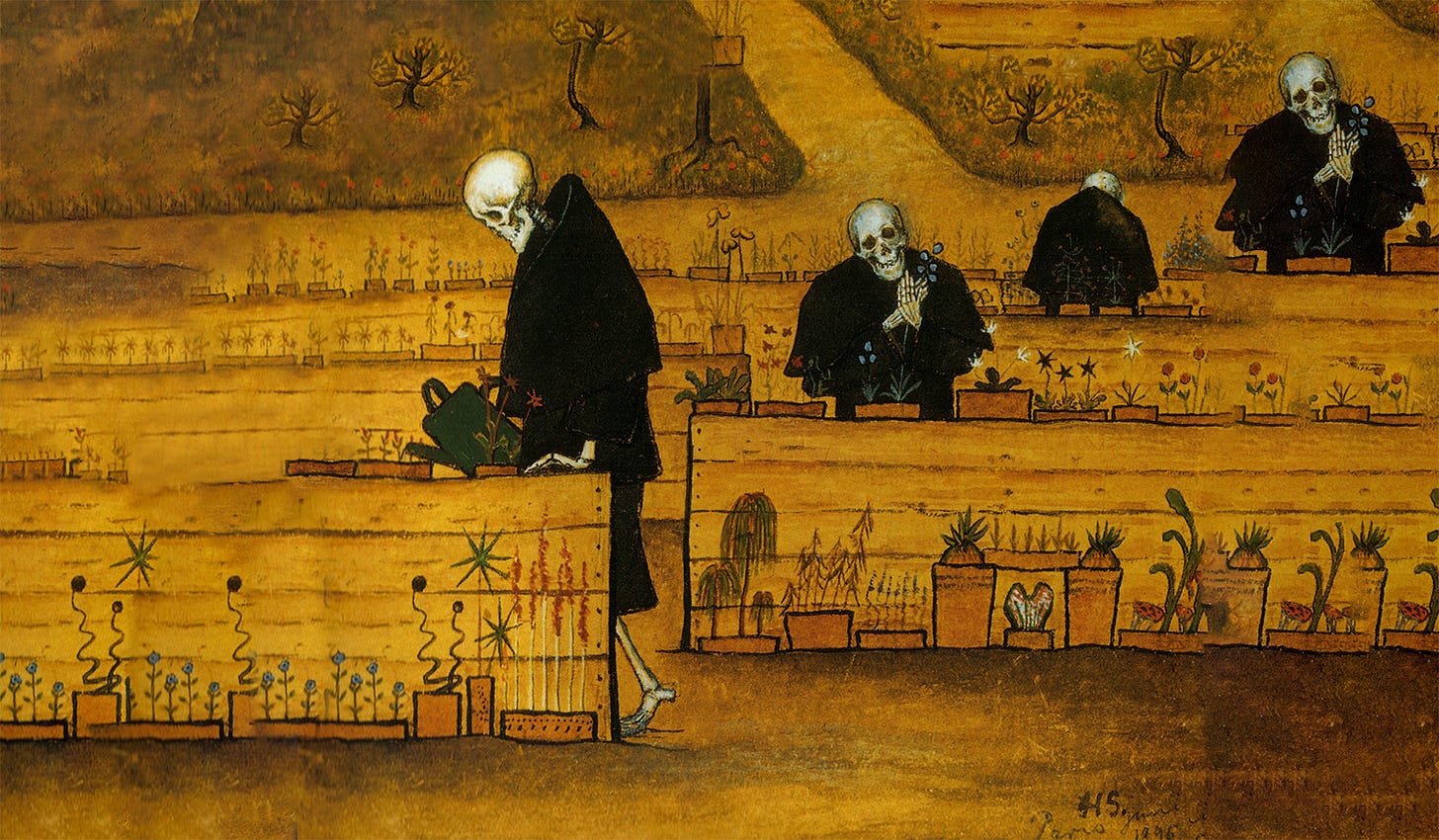

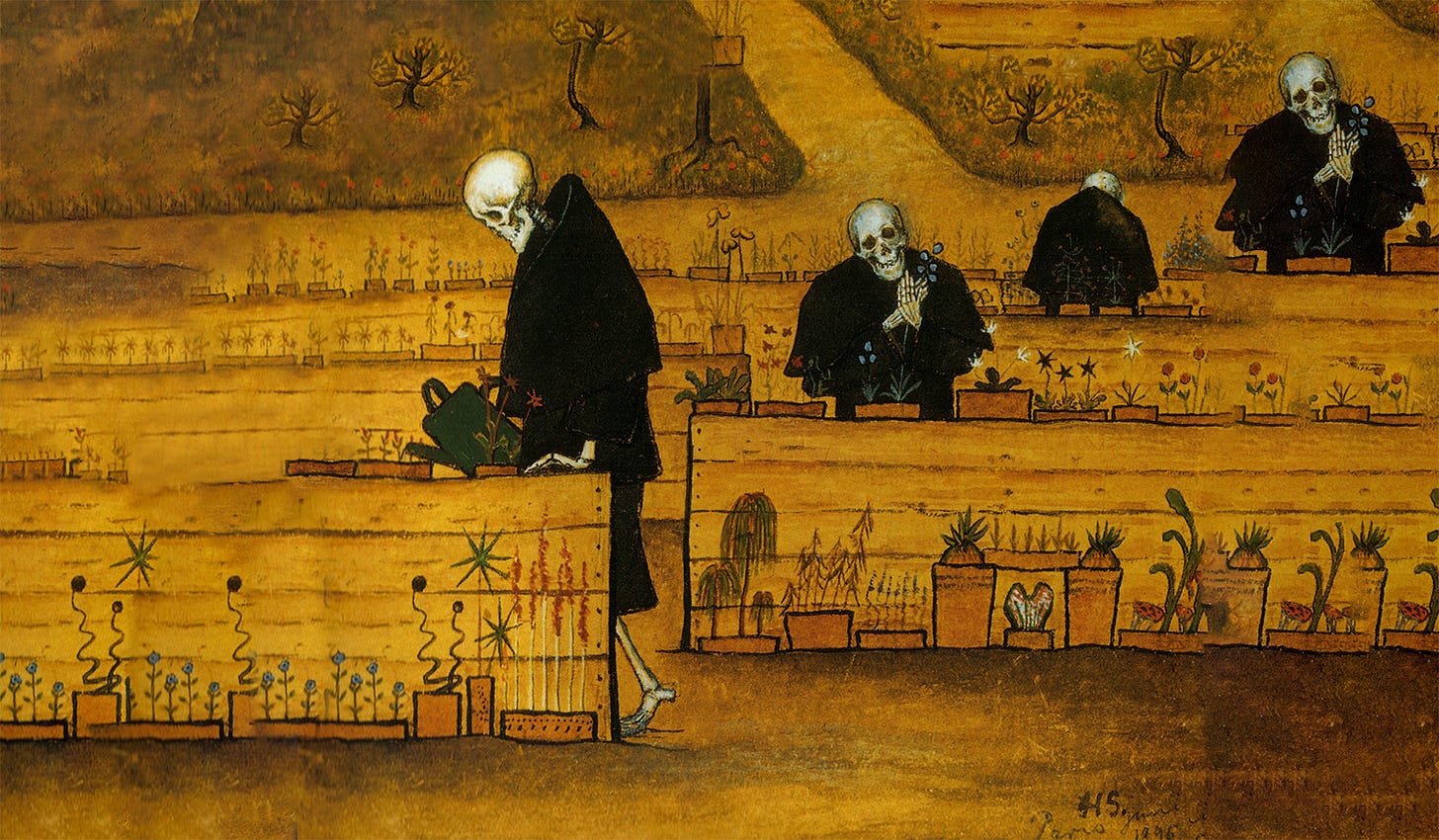

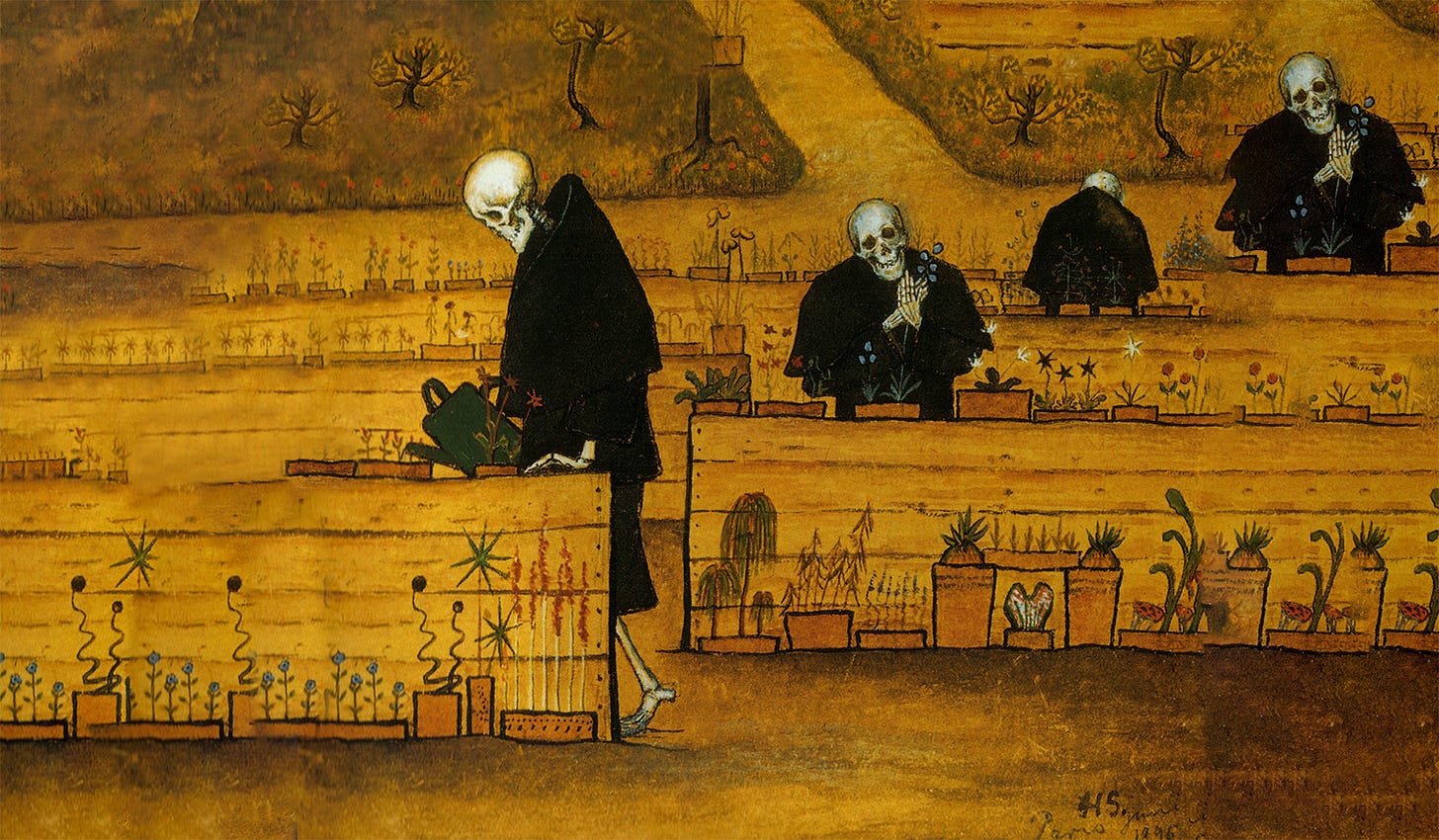

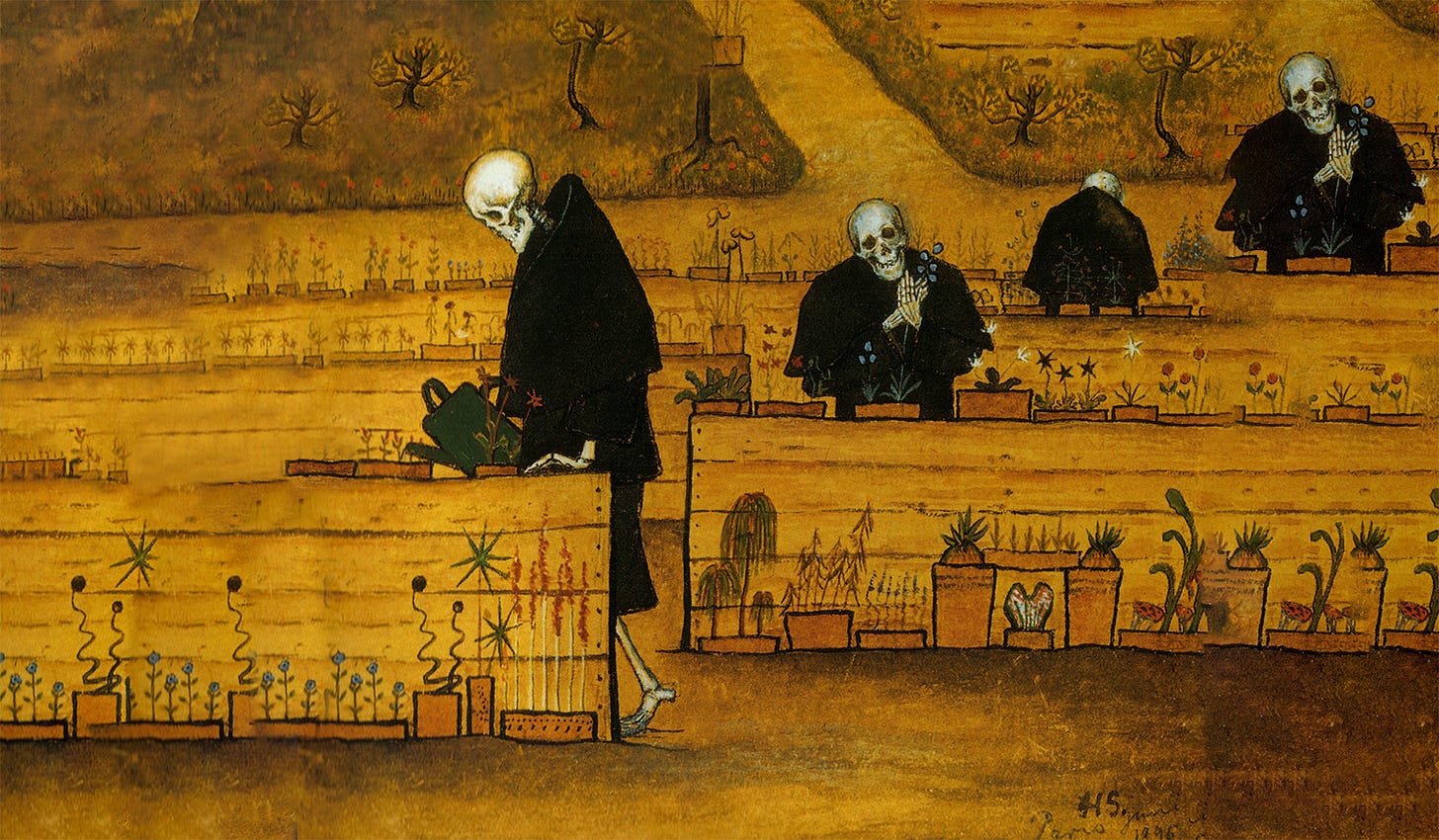

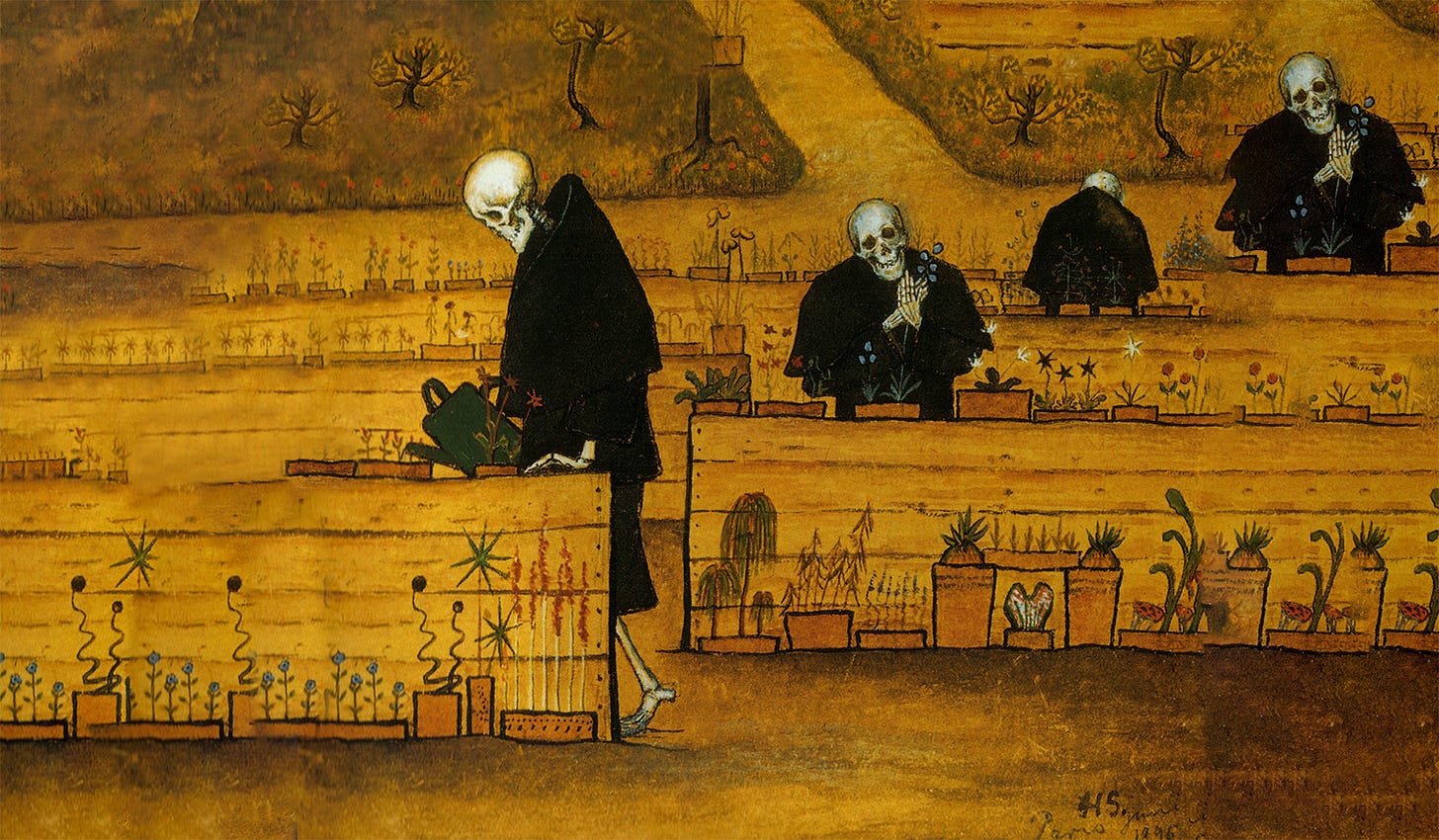

The Garden of Death by Hugo Simberg (via Wikimedia: Public Domain)

Connected to this society/self opposition is the binary opposition between the present and the past. The past is what society is loyal to. It wants us to respect the status quo – the way things are, the way the Bible tells us, or that the various authorities tell us.

“But the man in the street, finding no worth in himself which corresponds to the force which built a tower or sculptured a marble god, feels poor when he looks on these. To him a palace, a statue, or a costly book have an alien and forbidding air, much like a gay equipage, and seem to say like that, “Who are you, Sir?””

But Emerson reminds us that they are nothing without us.

“they all are his, suitors for his notice, petitioners to his faculties that they will come out and take possession. The picture waits for my verdict; it is not to command me, but I am to settle its claims to praise.”

This is what Emerson encourages most in us. It is being true to the voice of that aboriginal self and that can only happen in the present because it is not only the ancient authorities and the status quo that holds us in chains but it is our own past. In one of the lines from the essay that has stuck with me throughout the years he writes that:

“A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines. With consistency a great soul has simply nothing to do. He may as well concern himself with his shadow on the wall. Speak what you think now in hard words and tomorrow speak what tomorrow thinks in hard words again, though it contradict every thing you said to-day.”

This encouragement towards truth and integrity ties in with the divine spirit that the aboriginal self is tied up with. This spirit “shoves Jesus and Judas equally aside”. The great individual “belongs to no other time or place”. The roses under his window make:

“no reference to former roses or to better ones; they are for what they are; they exist with God to-day. There is no time to them. There is simply the rose; it is perfect in every moment of its existence.”

The truth is not something revealed millennia ago in the Bible or the Upanishads or any other sacred text. The truth – the divine spirit – disdains time. It is always in the present it is always here and now.

The past is dead. The present is where life always is:

“This one fact the world hates; that the soul becomes; for that forever degrades the past”

And so Emerson tells us to shun the words in the books, to shun the words of authorities and to attune ourselves to this inner voice to what our heart tells us to do. Following the course of this inner star you may appear inconsistent to those around you — today you are doing this and the next day you are onto something else. But, in an image that has been lodged in my mind since I first read Self-Reliance Emerson writes:

“The voyage of the best ship is a zigzag line of a hundred tacks. See the line from a sufficient distance, and it straightens itself to the average tendency. Your genuine action will explain itself and will explain your other genuine actions.”

Self-Reliance vs Conformity

All of which brings us to the central opposition of the text: Self-Reliance vs Conformity. Your conformity to Society’s demands “explains nothing” “But do your work, and I shall know you.”

In yet another story from Self-Reliance that has stayed with me over the years, and one of my favourite from any book, Emerson tells the story of a response he gave to an advisor of his who was trying to as he puts it importune him with the dear old doctrines of the church.

“‘On my saying, “What have I to do with the sacredness of traditions, if I live wholly from within?’ my friend suggested—‘But these impulses may be from below, not from above.’ I replied, ‘They do not seem to me to be such; but if I am the Devil’s child, I will live then from the Devil.’”

Which he follows up with the kicker:

“No law can be sacred to me but that of my nature. Good and bad are but names very readily transferable to that or this; the only right is what is after my constitution; the only wrong what is against it.”

This is Self-Reliance in a nutshell. It is setting aside what Society tells you to do. It is to put on a sour face if needs be and to above all be true to your principles – to honour truth above all things, to esteem what is right above the principles of those around you and to have “no law above truth’s”.

This is the way to genius. This is the way to greatness. It is to quieten the voices outside of you—to disengage from those external voices and to tune in to the inner Muse, to the aboriginal self, to the drumbeat of your own soul which may guide you hither and thither but there is a purpose in all the wandering. As Tolkien wrote ‘not all who wander are lost’.

In our modern civilised world Emerson sees that we are “afraid of truth, afraid of fortune, afraid of death, and afraid of each other.” But the greats — the self-reliant individuals embrace “the rugged battle of fate, where strength is born” and rather than dwelling on the past they walk abreast with their days.

And so Emerson tells us to go swim in the “internal ocean” and stop going to society to “beg a cup of water.”

In summary then Self-Reliance is a call for each of us to embrace our potential and to live fearlessly in obedience to our highest and deepest nature. It’s about setting aside the voices of the masses and past and to start living according to truth.

Emerson’s essay Self-Reliance was one of the first pieces of philosophy I ever read. And it was one of those fortuitous encounters that shaped my life in many ways. I first read it as a teenager at a crossroads in life; it was a time when big decisions about the future had to be made and Self-Reliance gave me the self-belief to dream more audaciously than my timid heart was temperamentally accustomed to.

It’s been a good few years since I sat down and went through the whole thing and so when I sat down recently and did just that I found myself blown away once again by this rhetorical masterpiece. If you’ve never read it I would recommend sitting down for five minutes and reading the first few paragraphs (link to full essay).

It’s an absolutely sublime bit of work and reading it today I can see how much it has coloured my worldview and shaped who I am. I don’t think of it that often anymore (except when certain lines from it bubble up to the front of my consciousness now and again) but, just as your average modern European doesn’t give much thought to the Ancient Greeks, there’s an archaeology of the soul whereby even things forgotten continue to shape us whether we are aware of them or not.

Reading it has yet again filled me with inspiration. Everything that I mean and everything that I feel with the words living philosophy is embodied in this essay. I can see foreshadowings of what Emerson would call The Living Philosophy’s “long foreground” in this essay. The inspiration was no doubt helped along this time by the more recently acquired knowledge that Emerson’s work was a pivotal influence on Nietzsche.

Obviously this time I had another intention when reading it as well and that was with the eye of a communicator. I was reading it with an eye to its essence with an eye to what it is about, how it unfolds, and why it is so amazing. And being quite a floral rhetorical piece rather than an argument made up of a series of propositions I actually had a bit of difficulty unearthing the structure.

I could go down a whole rabbit hole on this — it’s something I’ve thought about quite a lot recently with books and with all reading — the not so obvious art of how to read a book well. This time I thought I’d play with a lens that I picked up from my recent dabblings in Continental Philosophy and that is the idea of binary oppositions — essentially pairs of opposites — something I imagine we’ll be exploring in much more depth when we start talking about Derrida.

So I began looking for the binary oppositions in Emerson’s piece and I can only recommend this approach highly enough because it unlocked the whole essay for me. I could now see the things that Emerson valued both in their hallowed haloed form and in their shadow vice form. And so I thought that this might make an interesting way of approaching this essay of essays: through the medium of the binary oppositions that show what Emerson truly values. So this article is going to be an exploration of Emerson’s work through the lens of these binaries: greatness vs. meanness; the aboriginal self vs society; the dead past vs. the eternal present; and self-reliance vs. conformity.

Greatness vs. Meanness

A good binary opposition to start with that really sets the scene is Emerson’s dichotomy between greatness and meanness — or to use Nietzsche’s preferred term mediocrity. What the “great” value of Self-Reliance is seeking to bring about is the state of greatness. Emerson is concerned with the great people of history and he is encouraging us loyal readers to rise above the inertia of mediocrity and to attain the levels of human greatness.

The kind of people he has in mind aren’t just sages but statesmen, generals scientists and mystics. There’s Jesus and Socrates, Napoleon and Scipio, Pythagoras, Newton, Emmanuel Swedenborg, Diogenes, Zoroaster Washington, and Caesar.

These are all great individuals who left an indelible mark on the world. It wasn’t through the force of pen or sword that they did so but through the force of character. They were all self-reliant individuals who broke free from the gravity of society and were true to their inner genius. Emerson calls us to rise to the heights that are possible of humanity and to count ourselves among the greats rather than succumbing to the inertia of mediocrity.

Self vs Society

The second key binary opposition is between society and what Emerson calls the aboriginal Self.

This aboriginal self is the source of all genius, it is the source of virtue and of life. This source Emerson tells us can be called Spontaneity, Instinct or Intuition (after which “all later teachings are tuitions”).

So self-reliance then isn’t a reliance on a simple ego it’s not about becoming selfish. On the contrary Emerson tells us that the key trait of self-reliance is obedience and faith. It is following the course of this inner wisdom. He writes that he “Who has more obedience than I masters me, though he should not raise his finger.”

This following the self then isn’t about forcing our will on the world but it is to “allow a passage to its beams.” For those who have studied Jung, this immediately brings to mind his conception of the Self – the centre of consciousness around which our ego is to orbit and to be obedient to.

Over against this noble oversoul is Society. Society is Emerson’s big demon in Self-Reliance. It’s everything that the aboriginal self is not. For all the lightness of the aboriginal self, society is the darkening cheapening force in human life.

Society everywhere is in conspiracy against the manhood of every one of its members. Society is a joint-stock company, in which the members agree, for the better securing of his bread to each shareholder, to surrender the liberty and culture of the eater.

Under the influence of society, we tow the line of the shoulds and should nots. We become blinker-eyed members of “communities of opinion”. Society tames the genius of individuals who step out of line with what the mainstream says and greet the genius with sour faces but Emerson tells us “the sour faces of the multitude, like their sweet faces, have no deep cause, but are put on and off as the wind blows and a newspaper directs.”

Under the influence of society all of our virtues are impotent. The virtues of those allied to society are “penances” — it’s not something that bubbles up from within, it’s not an expression of this soul or spirit but something that is extorted, something done out of guilt.

This capitulation to society’s demands “scatters your force” and we are left muddied shadows of ourselves.

The Dead Past and the Eternal Present

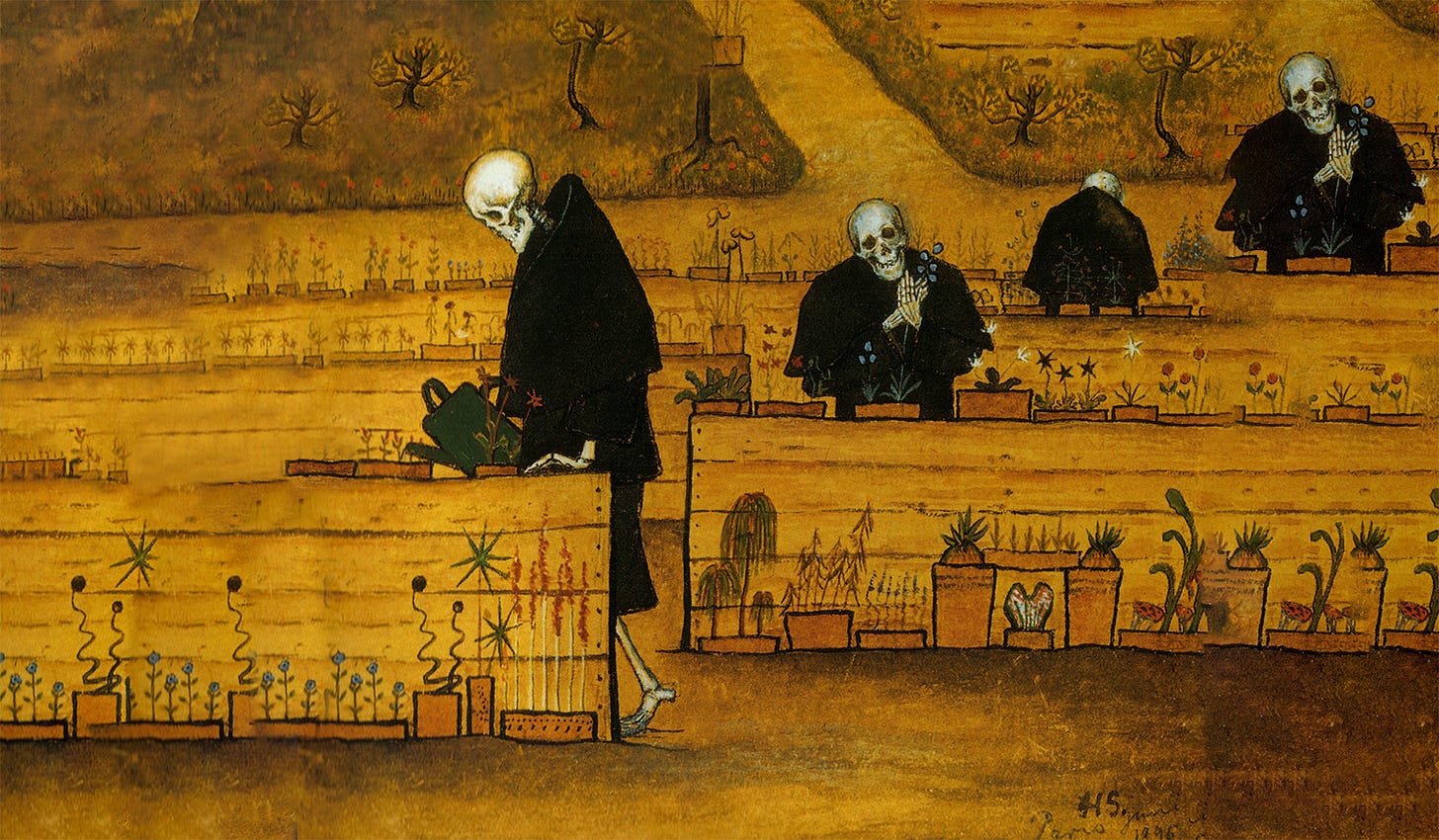

The Garden of Death by Hugo Simberg (via Wikimedia: Public Domain)

Connected to this society/self opposition is the binary opposition between the present and the past. The past is what society is loyal to. It wants us to respect the status quo – the way things are, the way the Bible tells us, or that the various authorities tell us.

“But the man in the street, finding no worth in himself which corresponds to the force which built a tower or sculptured a marble god, feels poor when he looks on these. To him a palace, a statue, or a costly book have an alien and forbidding air, much like a gay equipage, and seem to say like that, “Who are you, Sir?””

But Emerson reminds us that they are nothing without us.

“they all are his, suitors for his notice, petitioners to his faculties that they will come out and take possession. The picture waits for my verdict; it is not to command me, but I am to settle its claims to praise.”

This is what Emerson encourages most in us. It is being true to the voice of that aboriginal self and that can only happen in the present because it is not only the ancient authorities and the status quo that holds us in chains but it is our own past. In one of the lines from the essay that has stuck with me throughout the years he writes that:

“A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines. With consistency a great soul has simply nothing to do. He may as well concern himself with his shadow on the wall. Speak what you think now in hard words and tomorrow speak what tomorrow thinks in hard words again, though it contradict every thing you said to-day.”

This encouragement towards truth and integrity ties in with the divine spirit that the aboriginal self is tied up with. This spirit “shoves Jesus and Judas equally aside”. The great individual “belongs to no other time or place”. The roses under his window make:

“no reference to former roses or to better ones; they are for what they are; they exist with God to-day. There is no time to them. There is simply the rose; it is perfect in every moment of its existence.”

The truth is not something revealed millennia ago in the Bible or the Upanishads or any other sacred text. The truth – the divine spirit – disdains time. It is always in the present it is always here and now.

The past is dead. The present is where life always is:

“This one fact the world hates; that the soul becomes; for that forever degrades the past”

And so Emerson tells us to shun the words in the books, to shun the words of authorities and to attune ourselves to this inner voice to what our heart tells us to do. Following the course of this inner star you may appear inconsistent to those around you — today you are doing this and the next day you are onto something else. But, in an image that has been lodged in my mind since I first read Self-Reliance Emerson writes:

“The voyage of the best ship is a zigzag line of a hundred tacks. See the line from a sufficient distance, and it straightens itself to the average tendency. Your genuine action will explain itself and will explain your other genuine actions.”

Self-Reliance vs Conformity

All of which brings us to the central opposition of the text: Self-Reliance vs Conformity. Your conformity to Society’s demands “explains nothing” “But do your work, and I shall know you.”

In yet another story from Self-Reliance that has stayed with me over the years, and one of my favourite from any book, Emerson tells the story of a response he gave to an advisor of his who was trying to as he puts it importune him with the dear old doctrines of the church.

“‘On my saying, “What have I to do with the sacredness of traditions, if I live wholly from within?’ my friend suggested—‘But these impulses may be from below, not from above.’ I replied, ‘They do not seem to me to be such; but if I am the Devil’s child, I will live then from the Devil.’”

Which he follows up with the kicker:

“No law can be sacred to me but that of my nature. Good and bad are but names very readily transferable to that or this; the only right is what is after my constitution; the only wrong what is against it.”

This is Self-Reliance in a nutshell. It is setting aside what Society tells you to do. It is to put on a sour face if needs be and to above all be true to your principles – to honour truth above all things, to esteem what is right above the principles of those around you and to have “no law above truth’s”.

This is the way to genius. This is the way to greatness. It is to quieten the voices outside of you—to disengage from those external voices and to tune in to the inner Muse, to the aboriginal self, to the drumbeat of your own soul which may guide you hither and thither but there is a purpose in all the wandering. As Tolkien wrote ‘not all who wander are lost’.

In our modern civilised world Emerson sees that we are “afraid of truth, afraid of fortune, afraid of death, and afraid of each other.” But the greats — the self-reliant individuals embrace “the rugged battle of fate, where strength is born” and rather than dwelling on the past they walk abreast with their days.

And so Emerson tells us to go swim in the “internal ocean” and stop going to society to “beg a cup of water.”

In summary then Self-Reliance is a call for each of us to embrace our potential and to live fearlessly in obedience to our highest and deepest nature. It’s about setting aside the voices of the masses and past and to start living according to truth.

Leave A Comment

Emerson’s essay Self-Reliance was one of the first pieces of philosophy I ever read. And it was one of those fortuitous encounters that shaped my life in many ways. I first read it as a teenager at a crossroads in life; it was a time when big decisions about the future had to be made and Self-Reliance gave me the self-belief to dream more audaciously than my timid heart was temperamentally accustomed to.

It’s been a good few years since I sat down and went through the whole thing and so when I sat down recently and did just that I found myself blown away once again by this rhetorical masterpiece. If you’ve never read it I would recommend sitting down for five minutes and reading the first few paragraphs (link to full essay).

It’s an absolutely sublime bit of work and reading it today I can see how much it has coloured my worldview and shaped who I am. I don’t think of it that often anymore (except when certain lines from it bubble up to the front of my consciousness now and again) but, just as your average modern European doesn’t give much thought to the Ancient Greeks, there’s an archaeology of the soul whereby even things forgotten continue to shape us whether we are aware of them or not.

Reading it has yet again filled me with inspiration. Everything that I mean and everything that I feel with the words living philosophy is embodied in this essay. I can see foreshadowings of what Emerson would call The Living Philosophy’s “long foreground” in this essay. The inspiration was no doubt helped along this time by the more recently acquired knowledge that Emerson’s work was a pivotal influence on Nietzsche.

Obviously this time I had another intention when reading it as well and that was with the eye of a communicator. I was reading it with an eye to its essence with an eye to what it is about, how it unfolds, and why it is so amazing. And being quite a floral rhetorical piece rather than an argument made up of a series of propositions I actually had a bit of difficulty unearthing the structure.

I could go down a whole rabbit hole on this — it’s something I’ve thought about quite a lot recently with books and with all reading — the not so obvious art of how to read a book well. This time I thought I’d play with a lens that I picked up from my recent dabblings in Continental Philosophy and that is the idea of binary oppositions — essentially pairs of opposites — something I imagine we’ll be exploring in much more depth when we start talking about Derrida.

So I began looking for the binary oppositions in Emerson’s piece and I can only recommend this approach highly enough because it unlocked the whole essay for me. I could now see the things that Emerson valued both in their hallowed haloed form and in their shadow vice form. And so I thought that this might make an interesting way of approaching this essay of essays: through the medium of the binary oppositions that show what Emerson truly values. So this article is going to be an exploration of Emerson’s work through the lens of these binaries: greatness vs. meanness; the aboriginal self vs society; the dead past vs. the eternal present; and self-reliance vs. conformity.

Greatness vs. Meanness

A good binary opposition to start with that really sets the scene is Emerson’s dichotomy between greatness and meanness — or to use Nietzsche’s preferred term mediocrity. What the “great” value of Self-Reliance is seeking to bring about is the state of greatness. Emerson is concerned with the great people of history and he is encouraging us loyal readers to rise above the inertia of mediocrity and to attain the levels of human greatness.

The kind of people he has in mind aren’t just sages but statesmen, generals scientists and mystics. There’s Jesus and Socrates, Napoleon and Scipio, Pythagoras, Newton, Emmanuel Swedenborg, Diogenes, Zoroaster Washington, and Caesar.

These are all great individuals who left an indelible mark on the world. It wasn’t through the force of pen or sword that they did so but through the force of character. They were all self-reliant individuals who broke free from the gravity of society and were true to their inner genius. Emerson calls us to rise to the heights that are possible of humanity and to count ourselves among the greats rather than succumbing to the inertia of mediocrity.

Self vs Society

The second key binary opposition is between society and what Emerson calls the aboriginal Self.

This aboriginal self is the source of all genius, it is the source of virtue and of life. This source Emerson tells us can be called Spontaneity, Instinct or Intuition (after which “all later teachings are tuitions”).

So self-reliance then isn’t a reliance on a simple ego it’s not about becoming selfish. On the contrary Emerson tells us that the key trait of self-reliance is obedience and faith. It is following the course of this inner wisdom. He writes that he “Who has more obedience than I masters me, though he should not raise his finger.”

This following the self then isn’t about forcing our will on the world but it is to “allow a passage to its beams.” For those who have studied Jung, this immediately brings to mind his conception of the Self – the centre of consciousness around which our ego is to orbit and to be obedient to.

Over against this noble oversoul is Society. Society is Emerson’s big demon in Self-Reliance. It’s everything that the aboriginal self is not. For all the lightness of the aboriginal self, society is the darkening cheapening force in human life.

Society everywhere is in conspiracy against the manhood of every one of its members. Society is a joint-stock company, in which the members agree, for the better securing of his bread to each shareholder, to surrender the liberty and culture of the eater.

Under the influence of society, we tow the line of the shoulds and should nots. We become blinker-eyed members of “communities of opinion”. Society tames the genius of individuals who step out of line with what the mainstream says and greet the genius with sour faces but Emerson tells us “the sour faces of the multitude, like their sweet faces, have no deep cause, but are put on and off as the wind blows and a newspaper directs.”

Under the influence of society all of our virtues are impotent. The virtues of those allied to society are “penances” — it’s not something that bubbles up from within, it’s not an expression of this soul or spirit but something that is extorted, something done out of guilt.

This capitulation to society’s demands “scatters your force” and we are left muddied shadows of ourselves.

The Dead Past and the Eternal Present

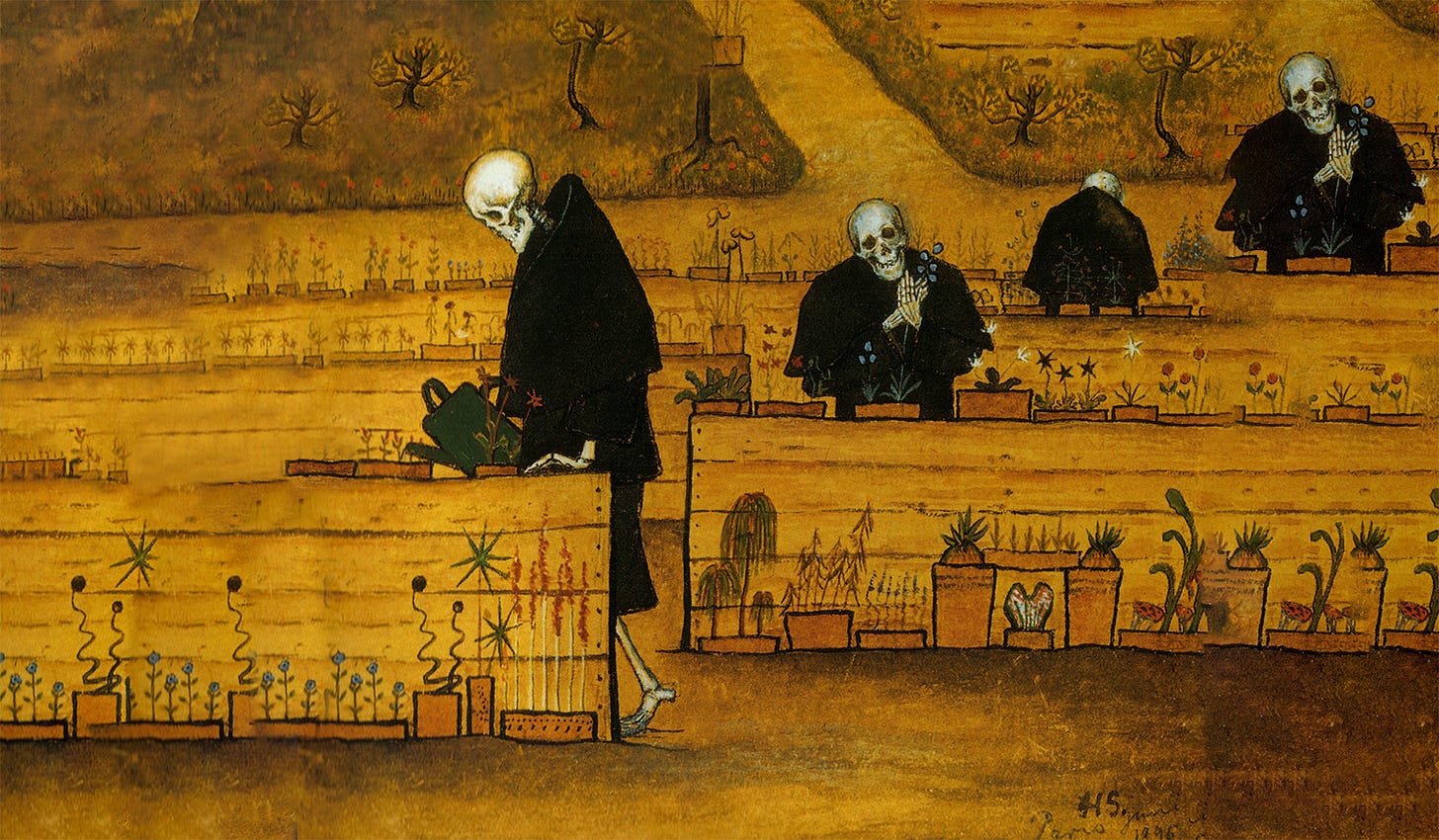

The Garden of Death by Hugo Simberg (via Wikimedia: Public Domain)

Connected to this society/self opposition is the binary opposition between the present and the past. The past is what society is loyal to. It wants us to respect the status quo – the way things are, the way the Bible tells us, or that the various authorities tell us.

“But the man in the street, finding no worth in himself which corresponds to the force which built a tower or sculptured a marble god, feels poor when he looks on these. To him a palace, a statue, or a costly book have an alien and forbidding air, much like a gay equipage, and seem to say like that, “Who are you, Sir?””

But Emerson reminds us that they are nothing without us.

“they all are his, suitors for his notice, petitioners to his faculties that they will come out and take possession. The picture waits for my verdict; it is not to command me, but I am to settle its claims to praise.”

This is what Emerson encourages most in us. It is being true to the voice of that aboriginal self and that can only happen in the present because it is not only the ancient authorities and the status quo that holds us in chains but it is our own past. In one of the lines from the essay that has stuck with me throughout the years he writes that:

“A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines. With consistency a great soul has simply nothing to do. He may as well concern himself with his shadow on the wall. Speak what you think now in hard words and tomorrow speak what tomorrow thinks in hard words again, though it contradict every thing you said to-day.”

This encouragement towards truth and integrity ties in with the divine spirit that the aboriginal self is tied up with. This spirit “shoves Jesus and Judas equally aside”. The great individual “belongs to no other time or place”. The roses under his window make:

“no reference to former roses or to better ones; they are for what they are; they exist with God to-day. There is no time to them. There is simply the rose; it is perfect in every moment of its existence.”

The truth is not something revealed millennia ago in the Bible or the Upanishads or any other sacred text. The truth – the divine spirit – disdains time. It is always in the present it is always here and now.

The past is dead. The present is where life always is:

“This one fact the world hates; that the soul becomes; for that forever degrades the past”

And so Emerson tells us to shun the words in the books, to shun the words of authorities and to attune ourselves to this inner voice to what our heart tells us to do. Following the course of this inner star you may appear inconsistent to those around you — today you are doing this and the next day you are onto something else. But, in an image that has been lodged in my mind since I first read Self-Reliance Emerson writes:

“The voyage of the best ship is a zigzag line of a hundred tacks. See the line from a sufficient distance, and it straightens itself to the average tendency. Your genuine action will explain itself and will explain your other genuine actions.”

Self-Reliance vs Conformity

All of which brings us to the central opposition of the text: Self-Reliance vs Conformity. Your conformity to Society’s demands “explains nothing” “But do your work, and I shall know you.”

In yet another story from Self-Reliance that has stayed with me over the years, and one of my favourite from any book, Emerson tells the story of a response he gave to an advisor of his who was trying to as he puts it importune him with the dear old doctrines of the church.

“‘On my saying, “What have I to do with the sacredness of traditions, if I live wholly from within?’ my friend suggested—‘But these impulses may be from below, not from above.’ I replied, ‘They do not seem to me to be such; but if I am the Devil’s child, I will live then from the Devil.’”

Which he follows up with the kicker:

“No law can be sacred to me but that of my nature. Good and bad are but names very readily transferable to that or this; the only right is what is after my constitution; the only wrong what is against it.”

This is Self-Reliance in a nutshell. It is setting aside what Society tells you to do. It is to put on a sour face if needs be and to above all be true to your principles – to honour truth above all things, to esteem what is right above the principles of those around you and to have “no law above truth’s”.

This is the way to genius. This is the way to greatness. It is to quieten the voices outside of you—to disengage from those external voices and to tune in to the inner Muse, to the aboriginal self, to the drumbeat of your own soul which may guide you hither and thither but there is a purpose in all the wandering. As Tolkien wrote ‘not all who wander are lost’.

In our modern civilised world Emerson sees that we are “afraid of truth, afraid of fortune, afraid of death, and afraid of each other.” But the greats — the self-reliant individuals embrace “the rugged battle of fate, where strength is born” and rather than dwelling on the past they walk abreast with their days.

And so Emerson tells us to go swim in the “internal ocean” and stop going to society to “beg a cup of water.”

In summary then Self-Reliance is a call for each of us to embrace our potential and to live fearlessly in obedience to our highest and deepest nature. It’s about setting aside the voices of the masses and past and to start living according to truth.