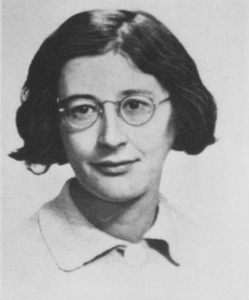

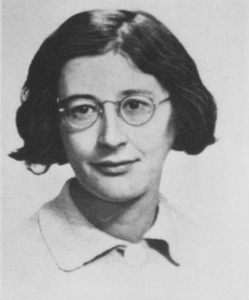

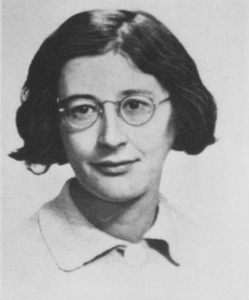

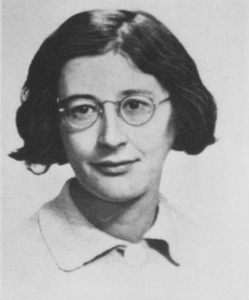

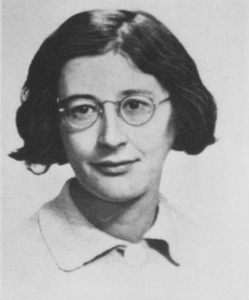

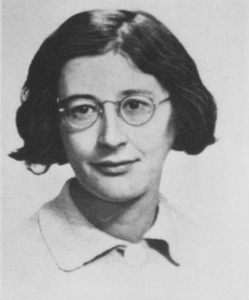

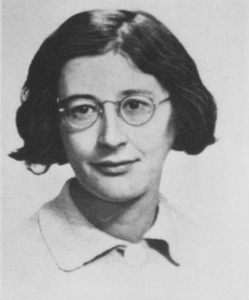

The Philosopher is a category that encapsulates a number of different types. There’s the theoretical masterminds like Aristotle, Kant and Hegel and there’s the unsystematic lightning rods like Nietzsche, Plato and Wittgenstein. But as well as these two mainstays there’s another type that we’ve explored in other articles on The Living Philosophy. This is the type whose philosophy is embodied more in their living than in their writing. Socrates is one of these as is Cato the Younger. This third category is the one that Simone Weil belongs in.

Before dying at the age of 34 Weil lived a life that shares with Socrates and Cato an eccentric and almost asinine integrity. Weil could not help but live her philosophy. For an introverted gentle soul she lived a life more vital and full than that of the most jaded rockstar. From working in factories to serving in wars, from academic studies to religious experiences, Simone Weil lived a life in her 34 years that encompassed the breadth of an era. In today’s article we are going to explore this illustrious life and the philosophy that underpinned it; why Albert Camus described her as “the only great spirit of our times”; T.S. Eliot described her as the greatest saint of the 20th century and why Charles de Gaulle called her insane.

Intellectual development and l’École Normale Supérieure

In 1928 Weil went to study General Philosophy and Logic at the prestigious Parisian university the École Normale Supérieure. She finished first in the entrance examination with Simone de Beauvoir finishing second. de Beauvoir later wrote of her sayingː

“I envied her for having a heart that could beat right across the world.”

During this time Weil’s radical views attracted much attention earning her the nickname of “The Red Virgin” among her peers while her teacher called her “The Martian”.

She is unusual among her intellectual peers. She lived in a sort of golden age of the public philosopher with many of her peers like de Beauvoir and Sartre and Camus becoming celebrities whose views were widely discussed. Despite coming from the same social milieu, Weil made no intimations of becoming a public philosopher. She just doesn’t seem to have paid attention to it and in tracking the moves she makes in her life and her philosophy we see a philosopher unfettered by any imposed boundaries. Ultimately she fit into no mould other than the one that was crafted by the dictates of her spirit.

After graduating she spent a number of years teaching philosophy in the early 1930’s and writing articles for socialist and communist periodicals. But more than this it was at this time that the larger-than-life Weil begins to emerge.

In 1932 she visited Germany to help Marxist activists there but from what she saw she believed they were no match for the fascist national socialists. On returning to France her fears were dismissed by her political friends but it was less than a year later that Hitler rose to power and banished the Communists from the political arena. After Hitler’s rise Weil spent much of her time helping communists escape from Germany.

In this minor incident we see all the seeds of Weil’s philosophy. She wasn’t content to look on the well-organised communist movement of Germany from a distance; she had to go see it for herself. And when things failed Weil could not wash her hands of the situation; her heart “that beat right across the world” as de Beauvoir described was compelled to help others where there was need.

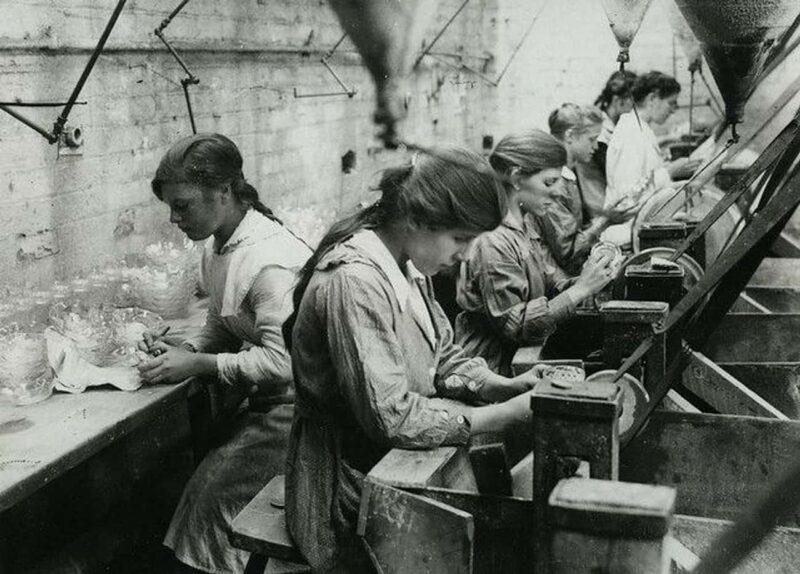

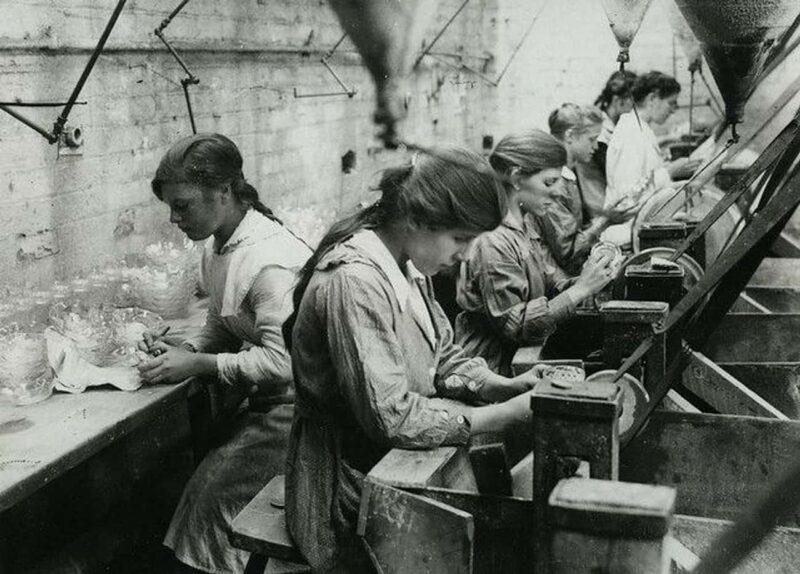

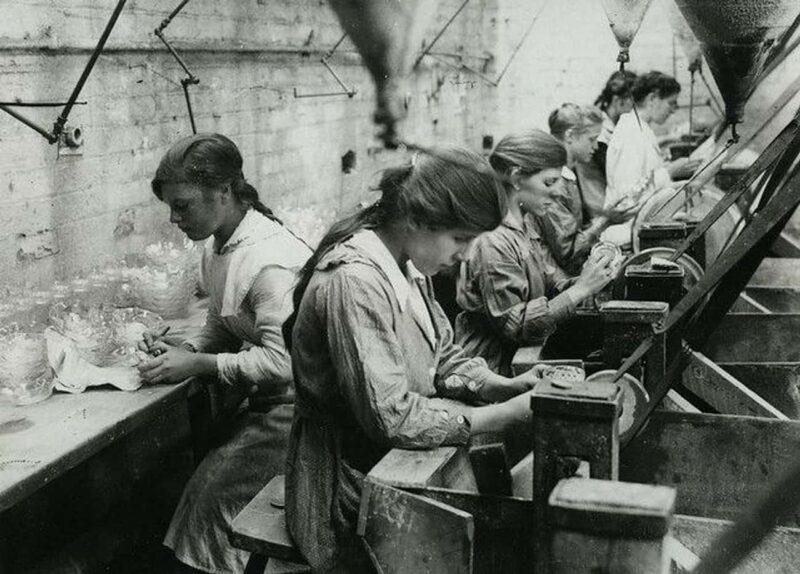

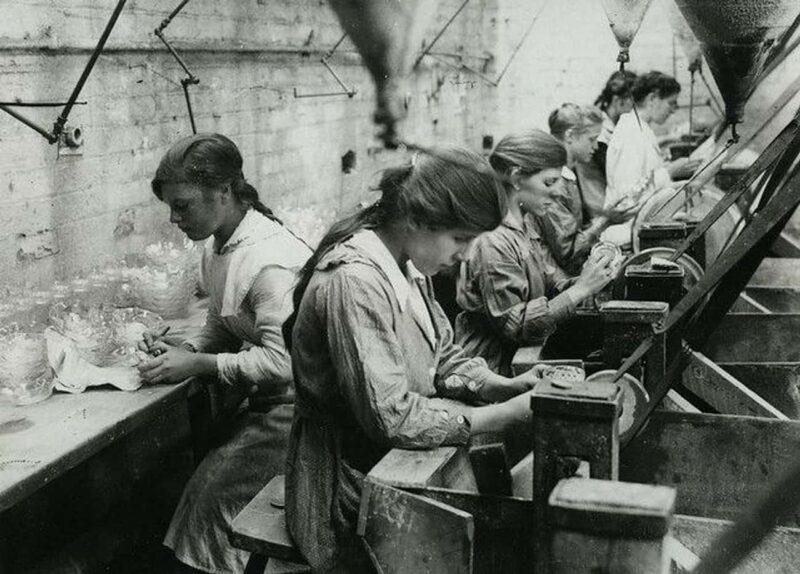

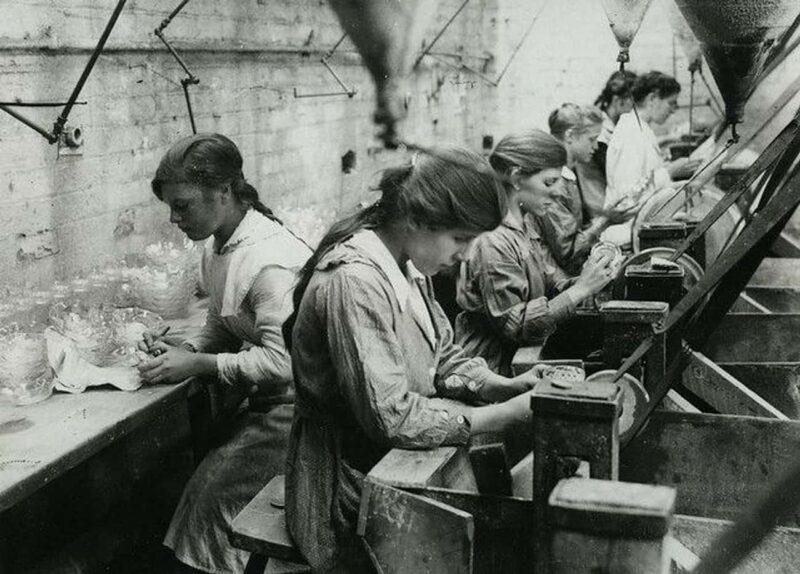

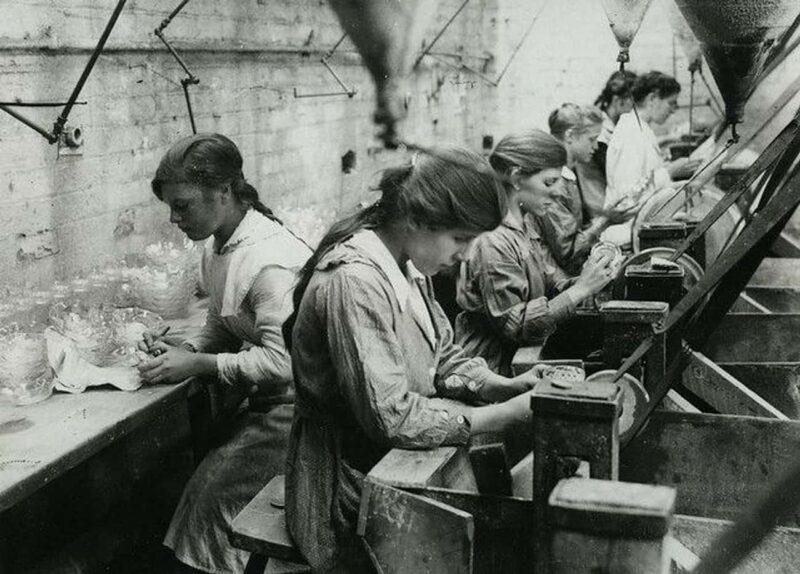

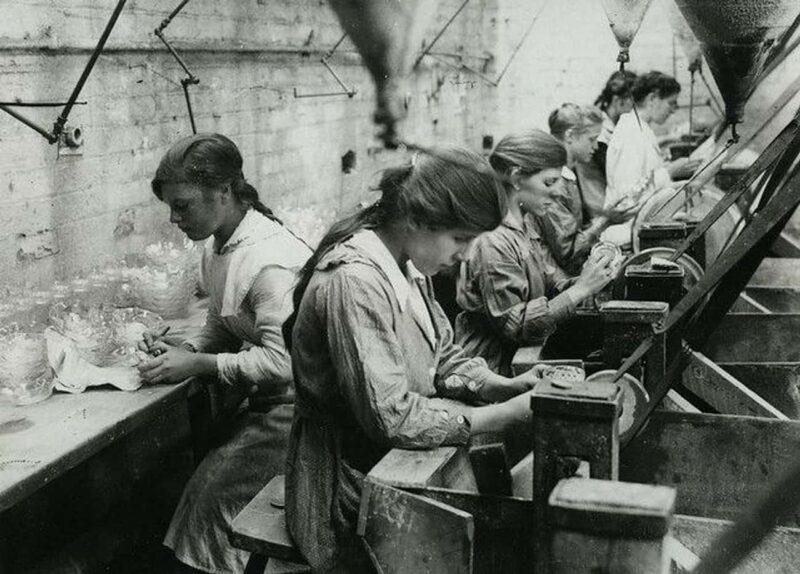

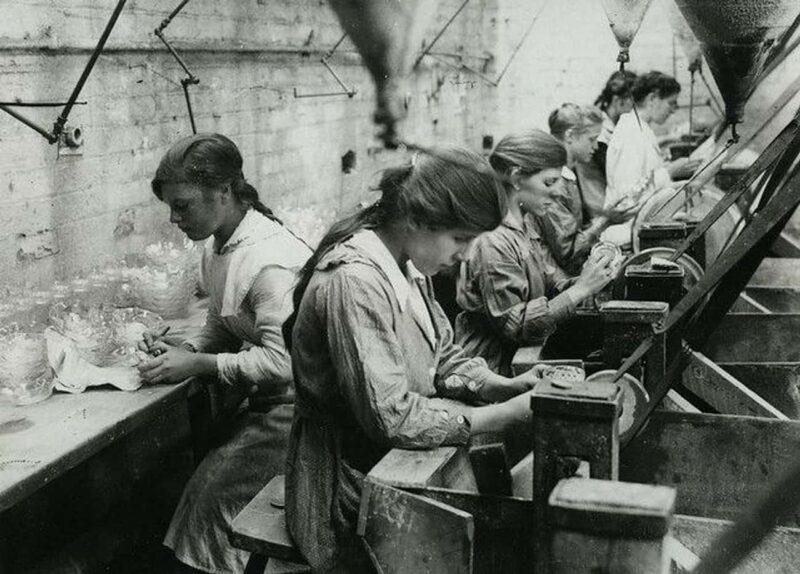

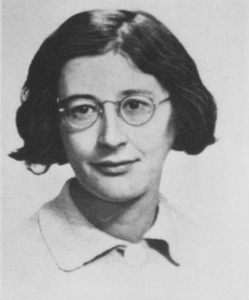

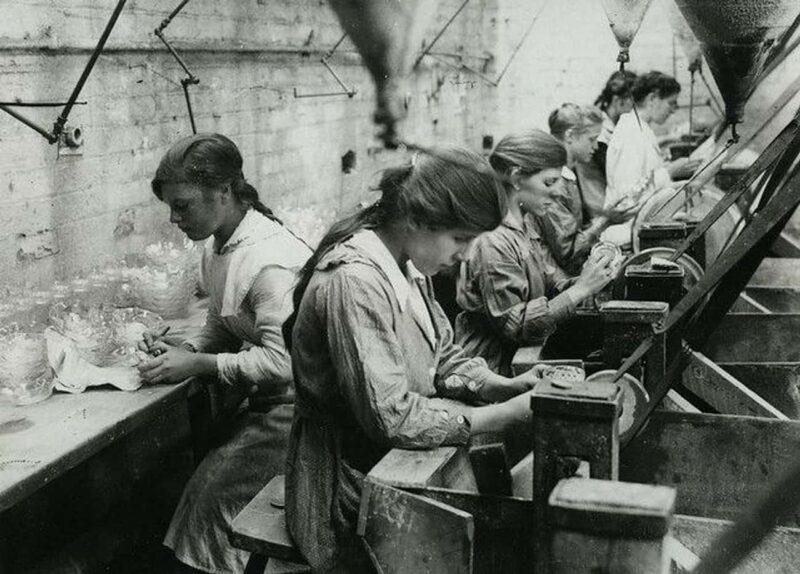

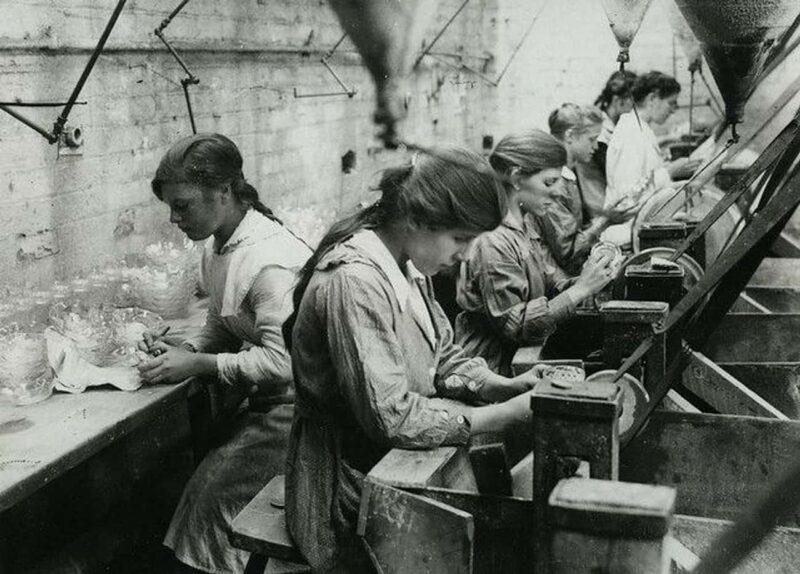

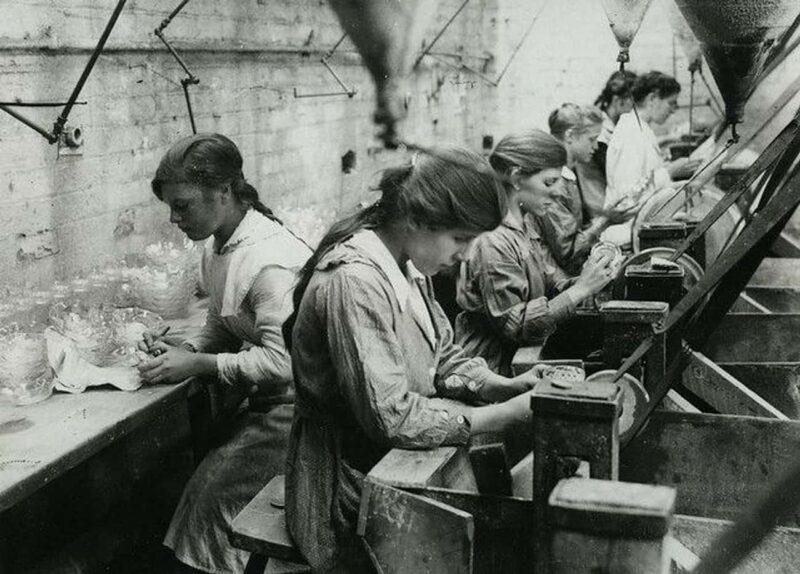

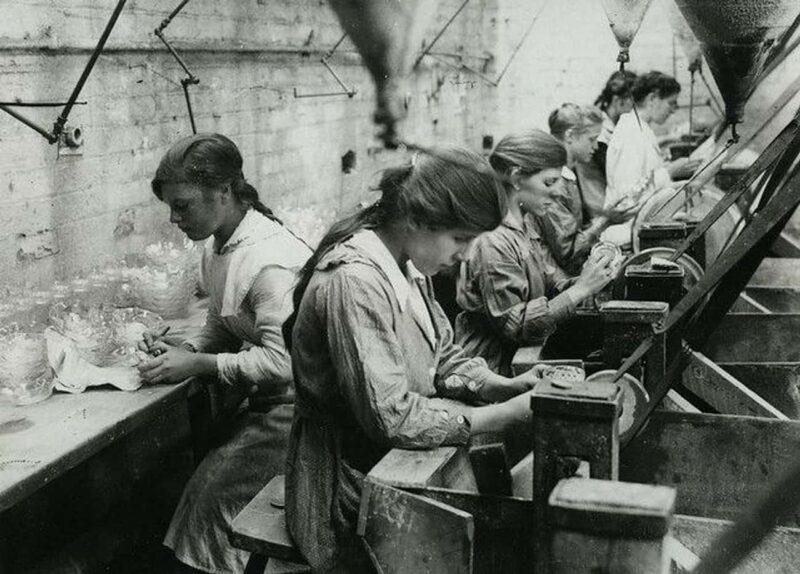

Simone the Factory Worker

On the 20th of June 1934, Weil applied for another break from her teaching work so that she could spend a year working in Parisian factories as part of its most oppressed group — unskilled female labourers. Once again Weil was not content to theoretically know about something that deeply concerned her; she had to go and experience it as much as possible.

Ultimately she spent 28 weeks working in a number of Parisian factories and it was a time that developed not just her political philosophy but it also sowed a critical seed in her religious unfoldment.

In this time her philosophy of oppression and slavery developed. She understood firsthand the normalisation of brutality in modern industry. In a journal from the time she wrote that “time was an intolerable burden”. Factory work consisted of two aspects: orders from superiors, and consequently, increased speeds of production.

She found that the increased demands and workload led to incredible fatigue and the death of all thinking. Her experience was less of a physical suffering but a soul-crushing humiliation. She was surprised to find that this humiliation didn’t produce rebellion but instead fatigue and docility. She described the whole experience as a kind of slavery.

In the autumn of the year after, she was in Portugal watching a procession to honour the patron saint of fishing villagers and she had her first major contact with Christianity. She wrote that:

the conviction was suddenly borne in upon me that Christianity is pre-eminently the religion of slaves, that slaves cannot help belonging to it, and I among others. (1942 “Spiritual Autobiography” in WFG 21–38, 26)

The Spanish Civil War and Christian Awakening

In 1936, she took part in the Paris factory occupations and planned on returning to factory work but her attention was directed Southward.

She reneged on her pacifism and went to take up arms in the Spanish Civil War. She sought out the anarchist faction and joined the French-speaking Durruti Column. Her time in Spain during the war while showing her courage and integrity, nevertheless reads like a comedy and more than explains George Bataille’s description of her as a Don Quixote.

Being extremely short-sighted, Weil was not the best shot and her comrades tried to avoid taking her with them on expeditions though she did sometimes insist. Her only experience of combat was to shoot her rifle at a bomber during an air raid. In a second raid she tried to man the group’s heavy machine gun but mercifully her comrades prevented her. Her time in the War came to an end when the clumsy and near sighted philosopher stepped in a pot of boiling oil severely burning her arm and instep.

She was forced to leave her unit and was convinced by her parents not to return but to take time to recover. And with that they departed for Assisi in Italy where she was to convalesce and have her second significant Christian experience. As she describes it in her Spiritual Autobiography:

“There, alone in the little twelfth-century Romanesque chapel of Santa Maria degli Angeli, an incomparable marvel of purity where Saint Francis often used to pray, something stronger than I compelled me for the first time in my life to go down on my knees.” (pp.67–8)

The following year she spent 10 days over the Easter period at a Benedictine community south west of Paris. She was suffering from crippling headaches at the time and the only succour she could find was in the Gregorian chanting of the monks. Despite the pain she found:

“a pure and perfect joy in the unimaginable beauty of the chanting and the words. This experience enabled me by analogy to get a better understanding of the possibility of loving divine love in the midst of affliction. It goes without saying that in the course of these services the thought of the Passion of Christ entered into my being once and for all.”

The final pivotal experience in Weil’s draw to Christianity came with her reading of George Herbert’s poem Love which she would repeat to herself over and over in the most disabling moments of her headaches. She believed at first that she was merely reciting the poem:

“but without my knowing it the recitation had the virtue of a prayer. It was during one of these recitations that, as I told you, Christ himself came down and took possession of me.”

With that Weil’s conversion to Christianity was complete. There was always something in her that leaned in this spiritual direction. She had studied Plato and the Neoplatonists as well as learning the India’s ancient sacred language Sanskrit so she could read the Bhagavat Gita in its original tongue. It was this affinity with a broader revelation of God that kept her from baptism but it was Christianity that spoke into the depths of her soul and permeated her life and thought from this time in 1938 until her death five years later.

For Weil, this baptism in the waters of mystical thinking was not an abandonment of her intellectual philosophical project but an extension of it. In her book, Waiting on God we see the importance of Attention which she sees as the critical part of experiencing a mystical communion with god. She writes that:

“The quality of the attention counts for much in the quality of the prayer. Warmth of heart cannot make up for it.”

And so for Weil, the cultivation of a religious life is not separate to the philosophical life but the culmination of it. The rigours of intellectual study provide the foundation for the relationship with God. She says that:

“School children and students who love God should never say: “For my part I like mathematics”; “I like French”; “I like Greek.” They should learn to like all these subjects, because all of them develop that faculty of attention which, directed toward God, is the very substance of prayer.”

For Weil this faculty of attention is key not just to prayer but to our ability to be live in solidarity and compassion with the suffering of our neighbours.

In her encounter with philosophy we see the crystallisation of Simone Weil the philosopher and Simone Weil the saintly lover of her fellow humans. Christianity bolstered and emphasised her native temperament.

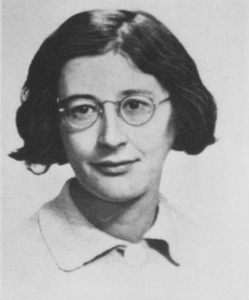

The Resistant and Her Death

When France was occupied by the Germans and Weil, who was Jewish by birth, escaped to the UK via the USA, she requested that she be parachuted into France as part of a squad of frontline nurses to help the Résistance. It was this plan of Weil’s that prompted the French leader in exile, General Charles de Gaulle to say “mais…elle est folle” — but she is insane.

The inertia that most of us experience that makes it difficult to live according to our higher values seems to be completely absent in Weil’s case; in fact the opposite seems true. She seems to have been incapable of not living out of her values. As she herself wrote in a notebook near the end of her life:

“Philosophy (including problems of cognition, etc.) is exclusively an affair of action and practice” (FLN 362).

This pattern is one that runs like a red thread through Weil’s whole life. She reminds me of other eccentrics in the history of philosophy like Henry David Thoreau and Ancient Rome’s Stoic senator Cato the Younger. To paraphrase Thoreau, we could say that

“If the woman does not keep pace with her companions, perhaps it is because she hears a different drummer. Let her step to the music which she hears, however measured or far away.”

And step to the music she heard she did. Weil like so many of the great philosophers was idiosyncratic enough that she was naturally separated from the herd of humanity. She wasn’t so effortlessly dissolved in the collective that she would end up marching to the same drummer as everyone else. When her heart called her to war she went to war; when her heart called her to religion when everyone else was talking about atheism, existentialism and nihilism, she loved God she breathed God and she lived God.

It was this plan of Weil’s that prompted the French leader in exile, General Charles de Gaulle to say “mais…elle est folle” — but she is insane.

And as with many other great philosophers, her death at the young age of 34 has become mythologised in the same way as the death of Socrates, the death of Cato and the madness of Nietzsche. On Tuesday the 24th of August 1943, Weil died in a hospital in Kent, England; three days later, the coroner pronounced the death a suicide — cardiac failure from self-starvation and tuberculosis.

The legend of her death says that Weil, aware that her fellow-countrymen in occupied territory had to live on minimal food rations at the time, insisted that she do the same. It was an act of solidarity and love that had no point to prove, it was not an attempt to wring a transformation from the world; it was Weil’s compulsion to suffer with her compatriots. This philosophy of suffering and compassion goes all the way to the core of her philosophy. In her book she writes that

“The better we are able to conceive of the fullness of joy, the purer and more intense will be our suffering in affliction and our compassion for others.”

— Gravity and Grace (chapter 16 ‘Affliction’)

This compassion ultimately exacerbated her own physical ailments and by the coroner’s account amounted to suicide. Her first English biographer Richard Rees summed it up by saying:

“As for her death, whatever explanation one may give of it will amount in the end to saying that she died of love.”

Of course not all sources are so taken in by this account. Others have argued that she didn’t die of starvation but that an inability to eat was a side effect of her illness. Others have said that her starvation was not in solidarity with those in occupied France but it was her following the ascetic advice of Arthur Schopenhauer who described self-starvation as the preferred method of self-denial. Whatever the case her death has become woven into her legend.

Final Thoughts

The life of Simone Weil illustrates the intricate and apparently contradictory dynamics of development. She grew up in an affluent bourgeoise family and yet she became an advocate for working-class rights and wrote for socialist and communist periodicals; she was originally a pacifist but then she became a solider on the frontlines of the Spanish Civil War; she was from a Jewish background and raised agnostic yet she became in the eyes of many a Christian mystic and saint. All of these developments might seem erratic and point to a changeable personality but Weil is one of those authentic originals that Ralph Waldo Emerson encourages us all to be in his essay Self-Reliance where he says that:

“The voyage of the best ship is a zigzag line of a hundred tacks. See the line from a sufficient distance, and it straightens itself to the average tendency. Your genuine action will explain itself and will explain your other genuine actions. Your conformity explains nothing.”

The Philosopher is a category that encapsulates a number of different types. There’s the theoretical masterminds like Aristotle, Kant and Hegel and there’s the unsystematic lightning rods like Nietzsche, Plato and Wittgenstein. But as well as these two mainstays there’s another type that we’ve explored in other articles on The Living Philosophy. This is the type whose philosophy is embodied more in their living than in their writing. Socrates is one of these as is Cato the Younger. This third category is the one that Simone Weil belongs in.

Before dying at the age of 34 Weil lived a life that shares with Socrates and Cato an eccentric and almost asinine integrity. Weil could not help but live her philosophy. For an introverted gentle soul she lived a life more vital and full than that of the most jaded rockstar. From working in factories to serving in wars, from academic studies to religious experiences, Simone Weil lived a life in her 34 years that encompassed the breadth of an era. In today’s article we are going to explore this illustrious life and the philosophy that underpinned it; why Albert Camus described her as “the only great spirit of our times”; T.S. Eliot described her as the greatest saint of the 20th century and why Charles de Gaulle called her insane.

Intellectual development and l’École Normale Supérieure

In 1928 Weil went to study General Philosophy and Logic at the prestigious Parisian university the École Normale Supérieure. She finished first in the entrance examination with Simone de Beauvoir finishing second. de Beauvoir later wrote of her sayingː

“I envied her for having a heart that could beat right across the world.”

During this time Weil’s radical views attracted much attention earning her the nickname of “The Red Virgin” among her peers while her teacher called her “The Martian”.

She is unusual among her intellectual peers. She lived in a sort of golden age of the public philosopher with many of her peers like de Beauvoir and Sartre and Camus becoming celebrities whose views were widely discussed. Despite coming from the same social milieu, Weil made no intimations of becoming a public philosopher. She just doesn’t seem to have paid attention to it and in tracking the moves she makes in her life and her philosophy we see a philosopher unfettered by any imposed boundaries. Ultimately she fit into no mould other than the one that was crafted by the dictates of her spirit.

After graduating she spent a number of years teaching philosophy in the early 1930’s and writing articles for socialist and communist periodicals. But more than this it was at this time that the larger-than-life Weil begins to emerge.

In 1932 she visited Germany to help Marxist activists there but from what she saw she believed they were no match for the fascist national socialists. On returning to France her fears were dismissed by her political friends but it was less than a year later that Hitler rose to power and banished the Communists from the political arena. After Hitler’s rise Weil spent much of her time helping communists escape from Germany.

In this minor incident we see all the seeds of Weil’s philosophy. She wasn’t content to look on the well-organised communist movement of Germany from a distance; she had to go see it for herself. And when things failed Weil could not wash her hands of the situation; her heart “that beat right across the world” as de Beauvoir described was compelled to help others where there was need.

Simone the Factory Worker

On the 20th of June 1934, Weil applied for another break from her teaching work so that she could spend a year working in Parisian factories as part of its most oppressed group — unskilled female labourers. Once again Weil was not content to theoretically know about something that deeply concerned her; she had to go and experience it as much as possible.

Ultimately she spent 28 weeks working in a number of Parisian factories and it was a time that developed not just her political philosophy but it also sowed a critical seed in her religious unfoldment.

In this time her philosophy of oppression and slavery developed. She understood firsthand the normalisation of brutality in modern industry. In a journal from the time she wrote that “time was an intolerable burden”. Factory work consisted of two aspects: orders from superiors, and consequently, increased speeds of production.

She found that the increased demands and workload led to incredible fatigue and the death of all thinking. Her experience was less of a physical suffering but a soul-crushing humiliation. She was surprised to find that this humiliation didn’t produce rebellion but instead fatigue and docility. She described the whole experience as a kind of slavery.

In the autumn of the year after, she was in Portugal watching a procession to honour the patron saint of fishing villagers and she had her first major contact with Christianity. She wrote that:

the conviction was suddenly borne in upon me that Christianity is pre-eminently the religion of slaves, that slaves cannot help belonging to it, and I among others. (1942 “Spiritual Autobiography” in WFG 21–38, 26)

The Spanish Civil War and Christian Awakening

In 1936, she took part in the Paris factory occupations and planned on returning to factory work but her attention was directed Southward.

She reneged on her pacifism and went to take up arms in the Spanish Civil War. She sought out the anarchist faction and joined the French-speaking Durruti Column. Her time in Spain during the war while showing her courage and integrity, nevertheless reads like a comedy and more than explains George Bataille’s description of her as a Don Quixote.

Being extremely short-sighted, Weil was not the best shot and her comrades tried to avoid taking her with them on expeditions though she did sometimes insist. Her only experience of combat was to shoot her rifle at a bomber during an air raid. In a second raid she tried to man the group’s heavy machine gun but mercifully her comrades prevented her. Her time in the War came to an end when the clumsy and near sighted philosopher stepped in a pot of boiling oil severely burning her arm and instep.

She was forced to leave her unit and was convinced by her parents not to return but to take time to recover. And with that they departed for Assisi in Italy where she was to convalesce and have her second significant Christian experience. As she describes it in her Spiritual Autobiography:

“There, alone in the little twelfth-century Romanesque chapel of Santa Maria degli Angeli, an incomparable marvel of purity where Saint Francis often used to pray, something stronger than I compelled me for the first time in my life to go down on my knees.” (pp.67–8)

The following year she spent 10 days over the Easter period at a Benedictine community south west of Paris. She was suffering from crippling headaches at the time and the only succour she could find was in the Gregorian chanting of the monks. Despite the pain she found:

“a pure and perfect joy in the unimaginable beauty of the chanting and the words. This experience enabled me by analogy to get a better understanding of the possibility of loving divine love in the midst of affliction. It goes without saying that in the course of these services the thought of the Passion of Christ entered into my being once and for all.”

The final pivotal experience in Weil’s draw to Christianity came with her reading of George Herbert’s poem Love which she would repeat to herself over and over in the most disabling moments of her headaches. She believed at first that she was merely reciting the poem:

“but without my knowing it the recitation had the virtue of a prayer. It was during one of these recitations that, as I told you, Christ himself came down and took possession of me.”

With that Weil’s conversion to Christianity was complete. There was always something in her that leaned in this spiritual direction. She had studied Plato and the Neoplatonists as well as learning the India’s ancient sacred language Sanskrit so she could read the Bhagavat Gita in its original tongue. It was this affinity with a broader revelation of God that kept her from baptism but it was Christianity that spoke into the depths of her soul and permeated her life and thought from this time in 1938 until her death five years later.

For Weil, this baptism in the waters of mystical thinking was not an abandonment of her intellectual philosophical project but an extension of it. In her book, Waiting on God we see the importance of Attention which she sees as the critical part of experiencing a mystical communion with god. She writes that:

“The quality of the attention counts for much in the quality of the prayer. Warmth of heart cannot make up for it.”

And so for Weil, the cultivation of a religious life is not separate to the philosophical life but the culmination of it. The rigours of intellectual study provide the foundation for the relationship with God. She says that:

“School children and students who love God should never say: “For my part I like mathematics”; “I like French”; “I like Greek.” They should learn to like all these subjects, because all of them develop that faculty of attention which, directed toward God, is the very substance of prayer.”

For Weil this faculty of attention is key not just to prayer but to our ability to be live in solidarity and compassion with the suffering of our neighbours.

In her encounter with philosophy we see the crystallisation of Simone Weil the philosopher and Simone Weil the saintly lover of her fellow humans. Christianity bolstered and emphasised her native temperament.

The Resistant and Her Death

When France was occupied by the Germans and Weil, who was Jewish by birth, escaped to the UK via the USA, she requested that she be parachuted into France as part of a squad of frontline nurses to help the Résistance. It was this plan of Weil’s that prompted the French leader in exile, General Charles de Gaulle to say “mais…elle est folle” — but she is insane.

The inertia that most of us experience that makes it difficult to live according to our higher values seems to be completely absent in Weil’s case; in fact the opposite seems true. She seems to have been incapable of not living out of her values. As she herself wrote in a notebook near the end of her life:

“Philosophy (including problems of cognition, etc.) is exclusively an affair of action and practice” (FLN 362).

This pattern is one that runs like a red thread through Weil’s whole life. She reminds me of other eccentrics in the history of philosophy like Henry David Thoreau and Ancient Rome’s Stoic senator Cato the Younger. To paraphrase Thoreau, we could say that

“If the woman does not keep pace with her companions, perhaps it is because she hears a different drummer. Let her step to the music which she hears, however measured or far away.”

And step to the music she heard she did. Weil like so many of the great philosophers was idiosyncratic enough that she was naturally separated from the herd of humanity. She wasn’t so effortlessly dissolved in the collective that she would end up marching to the same drummer as everyone else. When her heart called her to war she went to war; when her heart called her to religion when everyone else was talking about atheism, existentialism and nihilism, she loved God she breathed God and she lived God.

It was this plan of Weil’s that prompted the French leader in exile, General Charles de Gaulle to say “mais…elle est folle” — but she is insane.

And as with many other great philosophers, her death at the young age of 34 has become mythologised in the same way as the death of Socrates, the death of Cato and the madness of Nietzsche. On Tuesday the 24th of August 1943, Weil died in a hospital in Kent, England; three days later, the coroner pronounced the death a suicide — cardiac failure from self-starvation and tuberculosis.

The legend of her death says that Weil, aware that her fellow-countrymen in occupied territory had to live on minimal food rations at the time, insisted that she do the same. It was an act of solidarity and love that had no point to prove, it was not an attempt to wring a transformation from the world; it was Weil’s compulsion to suffer with her compatriots. This philosophy of suffering and compassion goes all the way to the core of her philosophy. In her book she writes that

“The better we are able to conceive of the fullness of joy, the purer and more intense will be our suffering in affliction and our compassion for others.”

— Gravity and Grace (chapter 16 ‘Affliction’)

This compassion ultimately exacerbated her own physical ailments and by the coroner’s account amounted to suicide. Her first English biographer Richard Rees summed it up by saying:

“As for her death, whatever explanation one may give of it will amount in the end to saying that she died of love.”

Of course not all sources are so taken in by this account. Others have argued that she didn’t die of starvation but that an inability to eat was a side effect of her illness. Others have said that her starvation was not in solidarity with those in occupied France but it was her following the ascetic advice of Arthur Schopenhauer who described self-starvation as the preferred method of self-denial. Whatever the case her death has become woven into her legend.

Final Thoughts

The life of Simone Weil illustrates the intricate and apparently contradictory dynamics of development. She grew up in an affluent bourgeoise family and yet she became an advocate for working-class rights and wrote for socialist and communist periodicals; she was originally a pacifist but then she became a solider on the frontlines of the Spanish Civil War; she was from a Jewish background and raised agnostic yet she became in the eyes of many a Christian mystic and saint. All of these developments might seem erratic and point to a changeable personality but Weil is one of those authentic originals that Ralph Waldo Emerson encourages us all to be in his essay Self-Reliance where he says that:

“The voyage of the best ship is a zigzag line of a hundred tacks. See the line from a sufficient distance, and it straightens itself to the average tendency. Your genuine action will explain itself and will explain your other genuine actions. Your conformity explains nothing.”

Leave A Comment

The Philosopher is a category that encapsulates a number of different types. There’s the theoretical masterminds like Aristotle, Kant and Hegel and there’s the unsystematic lightning rods like Nietzsche, Plato and Wittgenstein. But as well as these two mainstays there’s another type that we’ve explored in other articles on The Living Philosophy. This is the type whose philosophy is embodied more in their living than in their writing. Socrates is one of these as is Cato the Younger. This third category is the one that Simone Weil belongs in.

Before dying at the age of 34 Weil lived a life that shares with Socrates and Cato an eccentric and almost asinine integrity. Weil could not help but live her philosophy. For an introverted gentle soul she lived a life more vital and full than that of the most jaded rockstar. From working in factories to serving in wars, from academic studies to religious experiences, Simone Weil lived a life in her 34 years that encompassed the breadth of an era. In today’s article we are going to explore this illustrious life and the philosophy that underpinned it; why Albert Camus described her as “the only great spirit of our times”; T.S. Eliot described her as the greatest saint of the 20th century and why Charles de Gaulle called her insane.

Intellectual development and l’École Normale Supérieure

In 1928 Weil went to study General Philosophy and Logic at the prestigious Parisian university the École Normale Supérieure. She finished first in the entrance examination with Simone de Beauvoir finishing second. de Beauvoir later wrote of her sayingː

“I envied her for having a heart that could beat right across the world.”

During this time Weil’s radical views attracted much attention earning her the nickname of “The Red Virgin” among her peers while her teacher called her “The Martian”.

She is unusual among her intellectual peers. She lived in a sort of golden age of the public philosopher with many of her peers like de Beauvoir and Sartre and Camus becoming celebrities whose views were widely discussed. Despite coming from the same social milieu, Weil made no intimations of becoming a public philosopher. She just doesn’t seem to have paid attention to it and in tracking the moves she makes in her life and her philosophy we see a philosopher unfettered by any imposed boundaries. Ultimately she fit into no mould other than the one that was crafted by the dictates of her spirit.

After graduating she spent a number of years teaching philosophy in the early 1930’s and writing articles for socialist and communist periodicals. But more than this it was at this time that the larger-than-life Weil begins to emerge.

In 1932 she visited Germany to help Marxist activists there but from what she saw she believed they were no match for the fascist national socialists. On returning to France her fears were dismissed by her political friends but it was less than a year later that Hitler rose to power and banished the Communists from the political arena. After Hitler’s rise Weil spent much of her time helping communists escape from Germany.

In this minor incident we see all the seeds of Weil’s philosophy. She wasn’t content to look on the well-organised communist movement of Germany from a distance; she had to go see it for herself. And when things failed Weil could not wash her hands of the situation; her heart “that beat right across the world” as de Beauvoir described was compelled to help others where there was need.

Simone the Factory Worker

On the 20th of June 1934, Weil applied for another break from her teaching work so that she could spend a year working in Parisian factories as part of its most oppressed group — unskilled female labourers. Once again Weil was not content to theoretically know about something that deeply concerned her; she had to go and experience it as much as possible.

Ultimately she spent 28 weeks working in a number of Parisian factories and it was a time that developed not just her political philosophy but it also sowed a critical seed in her religious unfoldment.

In this time her philosophy of oppression and slavery developed. She understood firsthand the normalisation of brutality in modern industry. In a journal from the time she wrote that “time was an intolerable burden”. Factory work consisted of two aspects: orders from superiors, and consequently, increased speeds of production.

She found that the increased demands and workload led to incredible fatigue and the death of all thinking. Her experience was less of a physical suffering but a soul-crushing humiliation. She was surprised to find that this humiliation didn’t produce rebellion but instead fatigue and docility. She described the whole experience as a kind of slavery.

In the autumn of the year after, she was in Portugal watching a procession to honour the patron saint of fishing villagers and she had her first major contact with Christianity. She wrote that:

the conviction was suddenly borne in upon me that Christianity is pre-eminently the religion of slaves, that slaves cannot help belonging to it, and I among others. (1942 “Spiritual Autobiography” in WFG 21–38, 26)

The Spanish Civil War and Christian Awakening

In 1936, she took part in the Paris factory occupations and planned on returning to factory work but her attention was directed Southward.

She reneged on her pacifism and went to take up arms in the Spanish Civil War. She sought out the anarchist faction and joined the French-speaking Durruti Column. Her time in Spain during the war while showing her courage and integrity, nevertheless reads like a comedy and more than explains George Bataille’s description of her as a Don Quixote.

Being extremely short-sighted, Weil was not the best shot and her comrades tried to avoid taking her with them on expeditions though she did sometimes insist. Her only experience of combat was to shoot her rifle at a bomber during an air raid. In a second raid she tried to man the group’s heavy machine gun but mercifully her comrades prevented her. Her time in the War came to an end when the clumsy and near sighted philosopher stepped in a pot of boiling oil severely burning her arm and instep.

She was forced to leave her unit and was convinced by her parents not to return but to take time to recover. And with that they departed for Assisi in Italy where she was to convalesce and have her second significant Christian experience. As she describes it in her Spiritual Autobiography:

“There, alone in the little twelfth-century Romanesque chapel of Santa Maria degli Angeli, an incomparable marvel of purity where Saint Francis often used to pray, something stronger than I compelled me for the first time in my life to go down on my knees.” (pp.67–8)

The following year she spent 10 days over the Easter period at a Benedictine community south west of Paris. She was suffering from crippling headaches at the time and the only succour she could find was in the Gregorian chanting of the monks. Despite the pain she found:

“a pure and perfect joy in the unimaginable beauty of the chanting and the words. This experience enabled me by analogy to get a better understanding of the possibility of loving divine love in the midst of affliction. It goes without saying that in the course of these services the thought of the Passion of Christ entered into my being once and for all.”

The final pivotal experience in Weil’s draw to Christianity came with her reading of George Herbert’s poem Love which she would repeat to herself over and over in the most disabling moments of her headaches. She believed at first that she was merely reciting the poem:

“but without my knowing it the recitation had the virtue of a prayer. It was during one of these recitations that, as I told you, Christ himself came down and took possession of me.”

With that Weil’s conversion to Christianity was complete. There was always something in her that leaned in this spiritual direction. She had studied Plato and the Neoplatonists as well as learning the India’s ancient sacred language Sanskrit so she could read the Bhagavat Gita in its original tongue. It was this affinity with a broader revelation of God that kept her from baptism but it was Christianity that spoke into the depths of her soul and permeated her life and thought from this time in 1938 until her death five years later.

For Weil, this baptism in the waters of mystical thinking was not an abandonment of her intellectual philosophical project but an extension of it. In her book, Waiting on God we see the importance of Attention which she sees as the critical part of experiencing a mystical communion with god. She writes that:

“The quality of the attention counts for much in the quality of the prayer. Warmth of heart cannot make up for it.”

And so for Weil, the cultivation of a religious life is not separate to the philosophical life but the culmination of it. The rigours of intellectual study provide the foundation for the relationship with God. She says that:

“School children and students who love God should never say: “For my part I like mathematics”; “I like French”; “I like Greek.” They should learn to like all these subjects, because all of them develop that faculty of attention which, directed toward God, is the very substance of prayer.”

For Weil this faculty of attention is key not just to prayer but to our ability to be live in solidarity and compassion with the suffering of our neighbours.

In her encounter with philosophy we see the crystallisation of Simone Weil the philosopher and Simone Weil the saintly lover of her fellow humans. Christianity bolstered and emphasised her native temperament.

The Resistant and Her Death

When France was occupied by the Germans and Weil, who was Jewish by birth, escaped to the UK via the USA, she requested that she be parachuted into France as part of a squad of frontline nurses to help the Résistance. It was this plan of Weil’s that prompted the French leader in exile, General Charles de Gaulle to say “mais…elle est folle” — but she is insane.

The inertia that most of us experience that makes it difficult to live according to our higher values seems to be completely absent in Weil’s case; in fact the opposite seems true. She seems to have been incapable of not living out of her values. As she herself wrote in a notebook near the end of her life:

“Philosophy (including problems of cognition, etc.) is exclusively an affair of action and practice” (FLN 362).

This pattern is one that runs like a red thread through Weil’s whole life. She reminds me of other eccentrics in the history of philosophy like Henry David Thoreau and Ancient Rome’s Stoic senator Cato the Younger. To paraphrase Thoreau, we could say that

“If the woman does not keep pace with her companions, perhaps it is because she hears a different drummer. Let her step to the music which she hears, however measured or far away.”

And step to the music she heard she did. Weil like so many of the great philosophers was idiosyncratic enough that she was naturally separated from the herd of humanity. She wasn’t so effortlessly dissolved in the collective that she would end up marching to the same drummer as everyone else. When her heart called her to war she went to war; when her heart called her to religion when everyone else was talking about atheism, existentialism and nihilism, she loved God she breathed God and she lived God.

It was this plan of Weil’s that prompted the French leader in exile, General Charles de Gaulle to say “mais…elle est folle” — but she is insane.

And as with many other great philosophers, her death at the young age of 34 has become mythologised in the same way as the death of Socrates, the death of Cato and the madness of Nietzsche. On Tuesday the 24th of August 1943, Weil died in a hospital in Kent, England; three days later, the coroner pronounced the death a suicide — cardiac failure from self-starvation and tuberculosis.

The legend of her death says that Weil, aware that her fellow-countrymen in occupied territory had to live on minimal food rations at the time, insisted that she do the same. It was an act of solidarity and love that had no point to prove, it was not an attempt to wring a transformation from the world; it was Weil’s compulsion to suffer with her compatriots. This philosophy of suffering and compassion goes all the way to the core of her philosophy. In her book she writes that

“The better we are able to conceive of the fullness of joy, the purer and more intense will be our suffering in affliction and our compassion for others.”

— Gravity and Grace (chapter 16 ‘Affliction’)

This compassion ultimately exacerbated her own physical ailments and by the coroner’s account amounted to suicide. Her first English biographer Richard Rees summed it up by saying:

“As for her death, whatever explanation one may give of it will amount in the end to saying that she died of love.”

Of course not all sources are so taken in by this account. Others have argued that she didn’t die of starvation but that an inability to eat was a side effect of her illness. Others have said that her starvation was not in solidarity with those in occupied France but it was her following the ascetic advice of Arthur Schopenhauer who described self-starvation as the preferred method of self-denial. Whatever the case her death has become woven into her legend.

Final Thoughts

The life of Simone Weil illustrates the intricate and apparently contradictory dynamics of development. She grew up in an affluent bourgeoise family and yet she became an advocate for working-class rights and wrote for socialist and communist periodicals; she was originally a pacifist but then she became a solider on the frontlines of the Spanish Civil War; she was from a Jewish background and raised agnostic yet she became in the eyes of many a Christian mystic and saint. All of these developments might seem erratic and point to a changeable personality but Weil is one of those authentic originals that Ralph Waldo Emerson encourages us all to be in his essay Self-Reliance where he says that:

“The voyage of the best ship is a zigzag line of a hundred tacks. See the line from a sufficient distance, and it straightens itself to the average tendency. Your genuine action will explain itself and will explain your other genuine actions. Your conformity explains nothing.”