We all want to make the world a better place but where do we start?

This simple question cuts to the core of our polarised culture. It is the most straightforward litmus test for figuring out someone’s worldview.

Much like Dressgate 2015 — it’s a matter of perception that seems so fundamental that quite often those with different views struggle to believe that the other person is acting in good faith. When the disagreement is at the level of perception it feels impossible that another human could see it otherwise and it almost takes an act of faith to believe they are being genuine.

That infamous dress

One of the most economical ways of characterising the divide of the Culture Wars is as Individualists vs Collectivists. One side talks about making your bed and the other talks about systemic racism and sexism.

On The Living Philosophy, our tendency has been to focus on the Individualist side of this equation. Our perceptual premise is that the best way to improve the world is to start with ourselves. Following Voltaire’s Candide we say that we must cultivate our own garden. We start with ourselves and build an increasingly solid foundation from which to make a bigger and bigger impact on the world.

But there is a Collectivist point that stands against this Individualist one. On this view the Individualist is one of the poor souls in Plato’s Cave — trying to find salvation in a Shadow-show cast on the walls by the puppeteers above us.

In this instalment we are going to dive into a case study in which we can see the Individualist worldview as insufficient and where it seems to be better to put the Collective work ahead making our own bed.

Homelessness: A Collective Problem

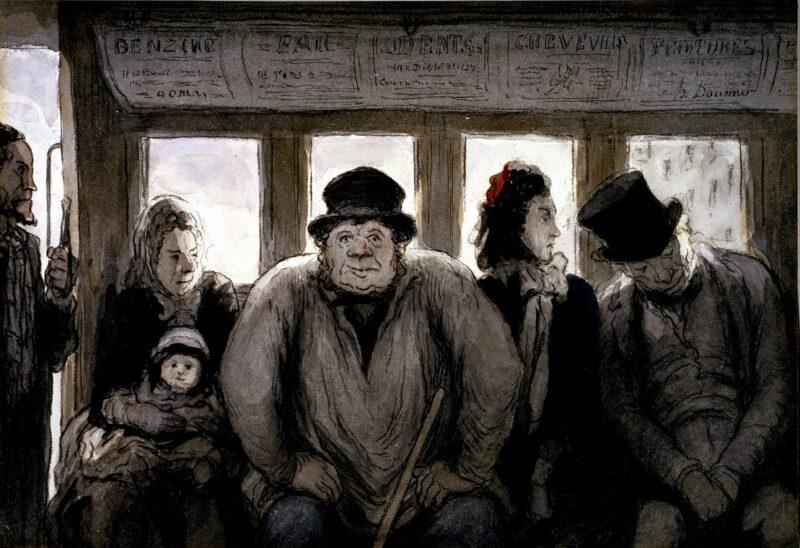

Homelessness is something we usually think of as a mental health or addiction problem. This is the most visible face of the problem. It’s the madman on the subway; the lads drinking cans and shouting at people in the park; it’s the carousel of tragedy you see on the YouTube channel Soft White Underbelly.

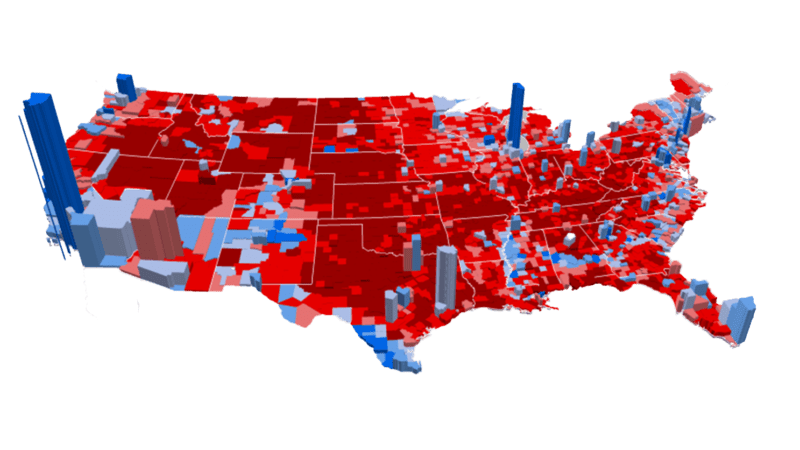

But if we look at homelessness in the United States at a collective level then a different picture begins to emerge. With the working hypothesis of mental health or addiction we might expect that where these problems are higher, rates of homelessness would be higher. But if we look at the map that’s not what’s going on. As Jerusalem Demsas put it in her article for The Atlantic:

If mental-health issues or drug abuse were major drivers of homelessness, then places with higher rates of these problems would see higher rates of homelessness. They don’t. Utah, Alabama, Colorado, Kentucky, West Virginia, Vermont, Delaware, and Wisconsin have some of the highest rates of mental illness in the country, but relatively modest homelessness levels. What prevents at-risk people in these states from falling into homelessness at high rates is simple: They have more affordable-housing options.

The same goes for poverty. You might think of homelessness as a poverty problem but in Detroit — one of the poorest cities in the US with a very high rate of poverty — homelessness is far lower than in New York or LA.

As Gregg Colburn and Clayton Page put it in their book Homelessness Is a Housing Problem:

“Homelessness is abundant only in areas with robust labor markets and low rates of unemployment — booming coastal cities.”

Homelessness is a problem of supply. It is highest in cities where real estate prices are highest.

Elliott Sclar, a professor of Urban Planning at Columbia University, has come up with a helpful analogy for understanding this situation: musical chairs. The first people to lose in musical chairs will be those hampered by some handicap like a sprained ankle. These initial losers are easy to predict. They are the visible face of homelessness — the Soft White Underbelly we pointed to earlier.

But to explain why homelessness is higher in the richest cities in America, you just have to let the game of musical chairs play a couple of rounds more. Once the most vulnerable candidates have already succumbed and the real estate prices continue to climb as demand far outstrips supply, it becomes more difficult to predict who is going to be left without a chair.

Instead of character vulnerability it becomes a question of circumstances. The ripples in the global economy might leave you without a job and fast forward a couple of months things begin to get hairy. If we look at the 2023 writers’ strike, this was the explicit strategy of the studios — their plan was to draw out the negotiations long enough that your average writer would struggle to pay their rent and would give in to the studios’ demands.

At this stage, it becomes a game of circumstance — of where and how the chairs are placed. Fewer and fewer chairs, more and more people without chairs. Not enough houses; fewer people with houses. It’s a simple equation. For every ten that pull that themselves up by their bootstraps, two find the chair kicked from under them by circumstances beyond their control.

A vicious circle

So we might ask: why is there a supply problem? According to Classical Economics the invisible hand of the market should take care of all this — meeting demand with supply. But it’s not so simple. The invisible hand runs into its perennial nemesis: regulation.

I want you to imagine a scenario. You live in one of these wealthy cities and you’ve fought tooth and claw for years to get together enough savings so you can just about afford a mortgage on a house. It’s extortionate but at least you can rest assured that the value will increase.

And then there’s a proposal to build some affordable housing down the road. There are a few reasons why this is not going to sit so well with you. For one you might reflect on the value of your house. The market is going to lower the price due to the proximity to this cheaper housing. You might imagine some of those crazy homeless people moving in which won’t merely affect the value of your house but perhaps the quality of your life.

Add to this the feeling that you’ve worked so hard for so long just to get your foot on the property ladder and some of these people are just going to be given a house. If you’re an idealist you’ll probably try to talk yourself down from these resentful bleedings from your Shadow. But the thrust of your instincts is going to throw you against this.

But, fortunately for you, there are regulations which allow you to protest this project. Affordable Housing is a wonderful idea you say but just not here. There are loads of places you could do it just please Not In My Back Yard. And so regulation-enabled NIMBY keeps affordable housing out of your neighbourhood and the value of your house is protected.

At an individualist scale this looks alright. They’ll just build the houses elsewhere. The trouble is that everywhere in these major cities is expensive and filled with people just like yourself who struggled to afford their houses and can’t afford to lose out there. It’s a circle of scarcity.

Conclusion

It’s a short case study but it has the power to challenge the base contention of our individualist approach to the world. If we move away from the individualist image of homeless people as the mad and addicted and look at the data which points to a deeper problem in the infrastructure a very different picture emerges which our self-actualisation philosophies are ill-equipped to deal with. The more problems like this in the system the more Equality of Opportunity becomes a distant ideal.

How can Candide cultivate his own garden when he’s living in a motel because the bank foreclosed on his home? How can you make your bed when you find yourself sleeping rough after a downturn in the economy?

We might be tempted to see these as edge cases — anomalies in The Matrix. And sure enough they are until you are the winner of this infernal lottery. And as the game progresses and there are less and less survivors in the game of musical chairs, it becomes less and less of an edge case.

That’s all for today’s instalment. Once again it’s a stepping aside from our usual explorations and situating them in a broader context. It’s a reminder that we aren’t just living through a Nihilistic crisis and a Meaning Crisis but a Metacrisis. 21st century society is loaded with challenges and in following our quest for a better life we have to situate ourselves in this bigger game.

This article is also a bit of groundwork for future instalments on Populism, Fascism, Marxism and other political and economic topics that are essential for understanding the bigger game we find ourselves playing even if we are unaware of it.

We all want to make the world a better place but where do we start?

This simple question cuts to the core of our polarised culture. It is the most straightforward litmus test for figuring out someone’s worldview.

Much like Dressgate 2015 — it’s a matter of perception that seems so fundamental that quite often those with different views struggle to believe that the other person is acting in good faith. When the disagreement is at the level of perception it feels impossible that another human could see it otherwise and it almost takes an act of faith to believe they are being genuine.

That infamous dress

One of the most economical ways of characterising the divide of the Culture Wars is as Individualists vs Collectivists. One side talks about making your bed and the other talks about systemic racism and sexism.

On The Living Philosophy, our tendency has been to focus on the Individualist side of this equation. Our perceptual premise is that the best way to improve the world is to start with ourselves. Following Voltaire’s Candide we say that we must cultivate our own garden. We start with ourselves and build an increasingly solid foundation from which to make a bigger and bigger impact on the world.

But there is a Collectivist point that stands against this Individualist one. On this view the Individualist is one of the poor souls in Plato’s Cave — trying to find salvation in a Shadow-show cast on the walls by the puppeteers above us.

In this instalment we are going to dive into a case study in which we can see the Individualist worldview as insufficient and where it seems to be better to put the Collective work ahead making our own bed.

Homelessness: A Collective Problem

Homelessness is something we usually think of as a mental health or addiction problem. This is the most visible face of the problem. It’s the madman on the subway; the lads drinking cans and shouting at people in the park; it’s the carousel of tragedy you see on the YouTube channel Soft White Underbelly.

But if we look at homelessness in the United States at a collective level then a different picture begins to emerge. With the working hypothesis of mental health or addiction we might expect that where these problems are higher, rates of homelessness would be higher. But if we look at the map that’s not what’s going on. As Jerusalem Demsas put it in her article for The Atlantic:

If mental-health issues or drug abuse were major drivers of homelessness, then places with higher rates of these problems would see higher rates of homelessness. They don’t. Utah, Alabama, Colorado, Kentucky, West Virginia, Vermont, Delaware, and Wisconsin have some of the highest rates of mental illness in the country, but relatively modest homelessness levels. What prevents at-risk people in these states from falling into homelessness at high rates is simple: They have more affordable-housing options.

The same goes for poverty. You might think of homelessness as a poverty problem but in Detroit — one of the poorest cities in the US with a very high rate of poverty — homelessness is far lower than in New York or LA.

As Gregg Colburn and Clayton Page put it in their book Homelessness Is a Housing Problem:

“Homelessness is abundant only in areas with robust labor markets and low rates of unemployment — booming coastal cities.”

Homelessness is a problem of supply. It is highest in cities where real estate prices are highest.

Elliott Sclar, a professor of Urban Planning at Columbia University, has come up with a helpful analogy for understanding this situation: musical chairs. The first people to lose in musical chairs will be those hampered by some handicap like a sprained ankle. These initial losers are easy to predict. They are the visible face of homelessness — the Soft White Underbelly we pointed to earlier.

But to explain why homelessness is higher in the richest cities in America, you just have to let the game of musical chairs play a couple of rounds more. Once the most vulnerable candidates have already succumbed and the real estate prices continue to climb as demand far outstrips supply, it becomes more difficult to predict who is going to be left without a chair.

Instead of character vulnerability it becomes a question of circumstances. The ripples in the global economy might leave you without a job and fast forward a couple of months things begin to get hairy. If we look at the 2023 writers’ strike, this was the explicit strategy of the studios — their plan was to draw out the negotiations long enough that your average writer would struggle to pay their rent and would give in to the studios’ demands.

At this stage, it becomes a game of circumstance — of where and how the chairs are placed. Fewer and fewer chairs, more and more people without chairs. Not enough houses; fewer people with houses. It’s a simple equation. For every ten that pull that themselves up by their bootstraps, two find the chair kicked from under them by circumstances beyond their control.

A vicious circle

So we might ask: why is there a supply problem? According to Classical Economics the invisible hand of the market should take care of all this — meeting demand with supply. But it’s not so simple. The invisible hand runs into its perennial nemesis: regulation.

I want you to imagine a scenario. You live in one of these wealthy cities and you’ve fought tooth and claw for years to get together enough savings so you can just about afford a mortgage on a house. It’s extortionate but at least you can rest assured that the value will increase.

And then there’s a proposal to build some affordable housing down the road. There are a few reasons why this is not going to sit so well with you. For one you might reflect on the value of your house. The market is going to lower the price due to the proximity to this cheaper housing. You might imagine some of those crazy homeless people moving in which won’t merely affect the value of your house but perhaps the quality of your life.

Add to this the feeling that you’ve worked so hard for so long just to get your foot on the property ladder and some of these people are just going to be given a house. If you’re an idealist you’ll probably try to talk yourself down from these resentful bleedings from your Shadow. But the thrust of your instincts is going to throw you against this.

But, fortunately for you, there are regulations which allow you to protest this project. Affordable Housing is a wonderful idea you say but just not here. There are loads of places you could do it just please Not In My Back Yard. And so regulation-enabled NIMBY keeps affordable housing out of your neighbourhood and the value of your house is protected.

At an individualist scale this looks alright. They’ll just build the houses elsewhere. The trouble is that everywhere in these major cities is expensive and filled with people just like yourself who struggled to afford their houses and can’t afford to lose out there. It’s a circle of scarcity.

Conclusion

It’s a short case study but it has the power to challenge the base contention of our individualist approach to the world. If we move away from the individualist image of homeless people as the mad and addicted and look at the data which points to a deeper problem in the infrastructure a very different picture emerges which our self-actualisation philosophies are ill-equipped to deal with. The more problems like this in the system the more Equality of Opportunity becomes a distant ideal.

How can Candide cultivate his own garden when he’s living in a motel because the bank foreclosed on his home? How can you make your bed when you find yourself sleeping rough after a downturn in the economy?

We might be tempted to see these as edge cases — anomalies in The Matrix. And sure enough they are until you are the winner of this infernal lottery. And as the game progresses and there are less and less survivors in the game of musical chairs, it becomes less and less of an edge case.

That’s all for today’s instalment. Once again it’s a stepping aside from our usual explorations and situating them in a broader context. It’s a reminder that we aren’t just living through a Nihilistic crisis and a Meaning Crisis but a Metacrisis. 21st century society is loaded with challenges and in following our quest for a better life we have to situate ourselves in this bigger game.

This article is also a bit of groundwork for future instalments on Populism, Fascism, Marxism and other political and economic topics that are essential for understanding the bigger game we find ourselves playing even if we are unaware of it.

Leave A Comment

We all want to make the world a better place but where do we start?

This simple question cuts to the core of our polarised culture. It is the most straightforward litmus test for figuring out someone’s worldview.

Much like Dressgate 2015 — it’s a matter of perception that seems so fundamental that quite often those with different views struggle to believe that the other person is acting in good faith. When the disagreement is at the level of perception it feels impossible that another human could see it otherwise and it almost takes an act of faith to believe they are being genuine.

That infamous dress

One of the most economical ways of characterising the divide of the Culture Wars is as Individualists vs Collectivists. One side talks about making your bed and the other talks about systemic racism and sexism.

On The Living Philosophy, our tendency has been to focus on the Individualist side of this equation. Our perceptual premise is that the best way to improve the world is to start with ourselves. Following Voltaire’s Candide we say that we must cultivate our own garden. We start with ourselves and build an increasingly solid foundation from which to make a bigger and bigger impact on the world.

But there is a Collectivist point that stands against this Individualist one. On this view the Individualist is one of the poor souls in Plato’s Cave — trying to find salvation in a Shadow-show cast on the walls by the puppeteers above us.

In this instalment we are going to dive into a case study in which we can see the Individualist worldview as insufficient and where it seems to be better to put the Collective work ahead making our own bed.

Homelessness: A Collective Problem

Homelessness is something we usually think of as a mental health or addiction problem. This is the most visible face of the problem. It’s the madman on the subway; the lads drinking cans and shouting at people in the park; it’s the carousel of tragedy you see on the YouTube channel Soft White Underbelly.

But if we look at homelessness in the United States at a collective level then a different picture begins to emerge. With the working hypothesis of mental health or addiction we might expect that where these problems are higher, rates of homelessness would be higher. But if we look at the map that’s not what’s going on. As Jerusalem Demsas put it in her article for The Atlantic:

If mental-health issues or drug abuse were major drivers of homelessness, then places with higher rates of these problems would see higher rates of homelessness. They don’t. Utah, Alabama, Colorado, Kentucky, West Virginia, Vermont, Delaware, and Wisconsin have some of the highest rates of mental illness in the country, but relatively modest homelessness levels. What prevents at-risk people in these states from falling into homelessness at high rates is simple: They have more affordable-housing options.

The same goes for poverty. You might think of homelessness as a poverty problem but in Detroit — one of the poorest cities in the US with a very high rate of poverty — homelessness is far lower than in New York or LA.

As Gregg Colburn and Clayton Page put it in their book Homelessness Is a Housing Problem:

“Homelessness is abundant only in areas with robust labor markets and low rates of unemployment — booming coastal cities.”

Homelessness is a problem of supply. It is highest in cities where real estate prices are highest.

Elliott Sclar, a professor of Urban Planning at Columbia University, has come up with a helpful analogy for understanding this situation: musical chairs. The first people to lose in musical chairs will be those hampered by some handicap like a sprained ankle. These initial losers are easy to predict. They are the visible face of homelessness — the Soft White Underbelly we pointed to earlier.

But to explain why homelessness is higher in the richest cities in America, you just have to let the game of musical chairs play a couple of rounds more. Once the most vulnerable candidates have already succumbed and the real estate prices continue to climb as demand far outstrips supply, it becomes more difficult to predict who is going to be left without a chair.

Instead of character vulnerability it becomes a question of circumstances. The ripples in the global economy might leave you without a job and fast forward a couple of months things begin to get hairy. If we look at the 2023 writers’ strike, this was the explicit strategy of the studios — their plan was to draw out the negotiations long enough that your average writer would struggle to pay their rent and would give in to the studios’ demands.

At this stage, it becomes a game of circumstance — of where and how the chairs are placed. Fewer and fewer chairs, more and more people without chairs. Not enough houses; fewer people with houses. It’s a simple equation. For every ten that pull that themselves up by their bootstraps, two find the chair kicked from under them by circumstances beyond their control.

A vicious circle

So we might ask: why is there a supply problem? According to Classical Economics the invisible hand of the market should take care of all this — meeting demand with supply. But it’s not so simple. The invisible hand runs into its perennial nemesis: regulation.

I want you to imagine a scenario. You live in one of these wealthy cities and you’ve fought tooth and claw for years to get together enough savings so you can just about afford a mortgage on a house. It’s extortionate but at least you can rest assured that the value will increase.

And then there’s a proposal to build some affordable housing down the road. There are a few reasons why this is not going to sit so well with you. For one you might reflect on the value of your house. The market is going to lower the price due to the proximity to this cheaper housing. You might imagine some of those crazy homeless people moving in which won’t merely affect the value of your house but perhaps the quality of your life.

Add to this the feeling that you’ve worked so hard for so long just to get your foot on the property ladder and some of these people are just going to be given a house. If you’re an idealist you’ll probably try to talk yourself down from these resentful bleedings from your Shadow. But the thrust of your instincts is going to throw you against this.

But, fortunately for you, there are regulations which allow you to protest this project. Affordable Housing is a wonderful idea you say but just not here. There are loads of places you could do it just please Not In My Back Yard. And so regulation-enabled NIMBY keeps affordable housing out of your neighbourhood and the value of your house is protected.

At an individualist scale this looks alright. They’ll just build the houses elsewhere. The trouble is that everywhere in these major cities is expensive and filled with people just like yourself who struggled to afford their houses and can’t afford to lose out there. It’s a circle of scarcity.

Conclusion

It’s a short case study but it has the power to challenge the base contention of our individualist approach to the world. If we move away from the individualist image of homeless people as the mad and addicted and look at the data which points to a deeper problem in the infrastructure a very different picture emerges which our self-actualisation philosophies are ill-equipped to deal with. The more problems like this in the system the more Equality of Opportunity becomes a distant ideal.

How can Candide cultivate his own garden when he’s living in a motel because the bank foreclosed on his home? How can you make your bed when you find yourself sleeping rough after a downturn in the economy?

We might be tempted to see these as edge cases — anomalies in The Matrix. And sure enough they are until you are the winner of this infernal lottery. And as the game progresses and there are less and less survivors in the game of musical chairs, it becomes less and less of an edge case.

That’s all for today’s instalment. Once again it’s a stepping aside from our usual explorations and situating them in a broader context. It’s a reminder that we aren’t just living through a Nihilistic crisis and a Meaning Crisis but a Metacrisis. 21st century society is loaded with challenges and in following our quest for a better life we have to situate ourselves in this bigger game.

This article is also a bit of groundwork for future instalments on Populism, Fascism, Marxism and other political and economic topics that are essential for understanding the bigger game we find ourselves playing even if we are unaware of it.