Why is it that, so often, when we commit to being the best version of ourselves, we succumb to embodying a cliché, a person seemingly far from who we think we should be.

For example, a person commits to a diet. They have a vision of the person they want to be and make a commitment to reaching that desired goal.

And then, late in the night, we see that same individual — illuminated by the glow of the fridge — wolfing down cheesecake.

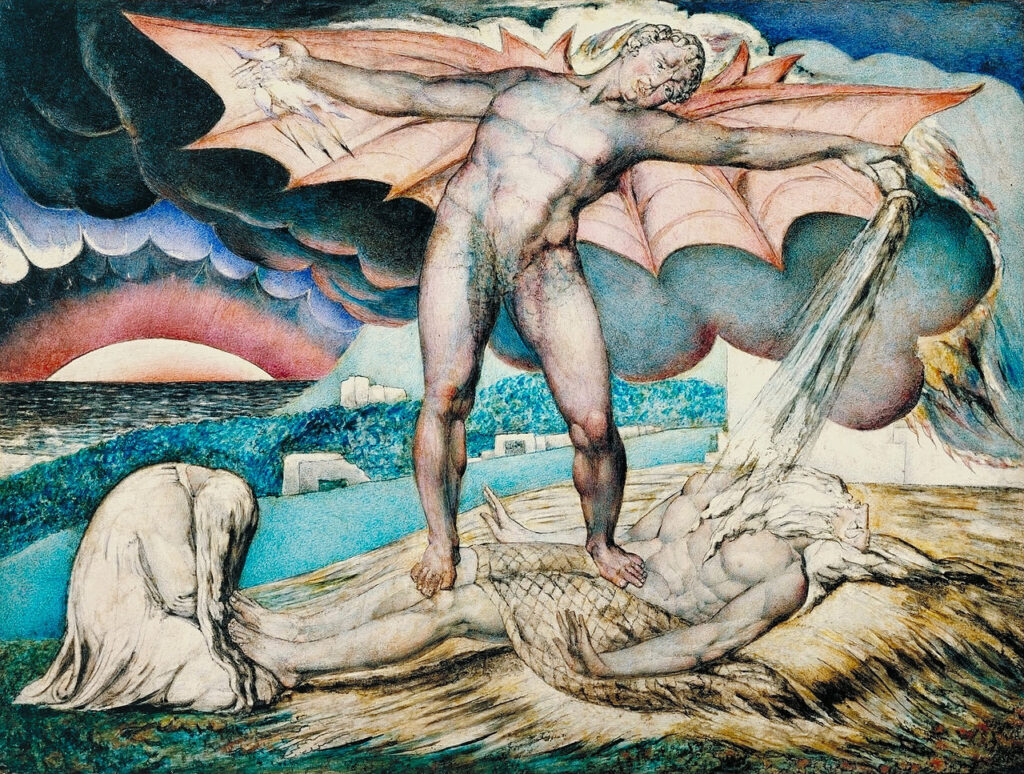

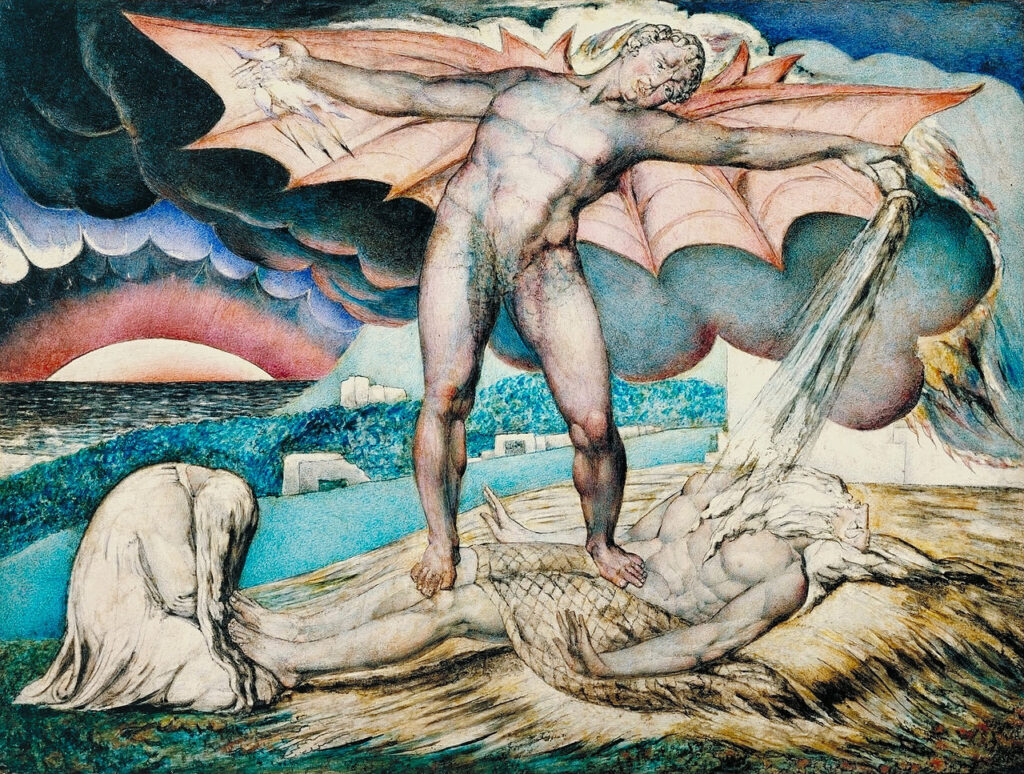

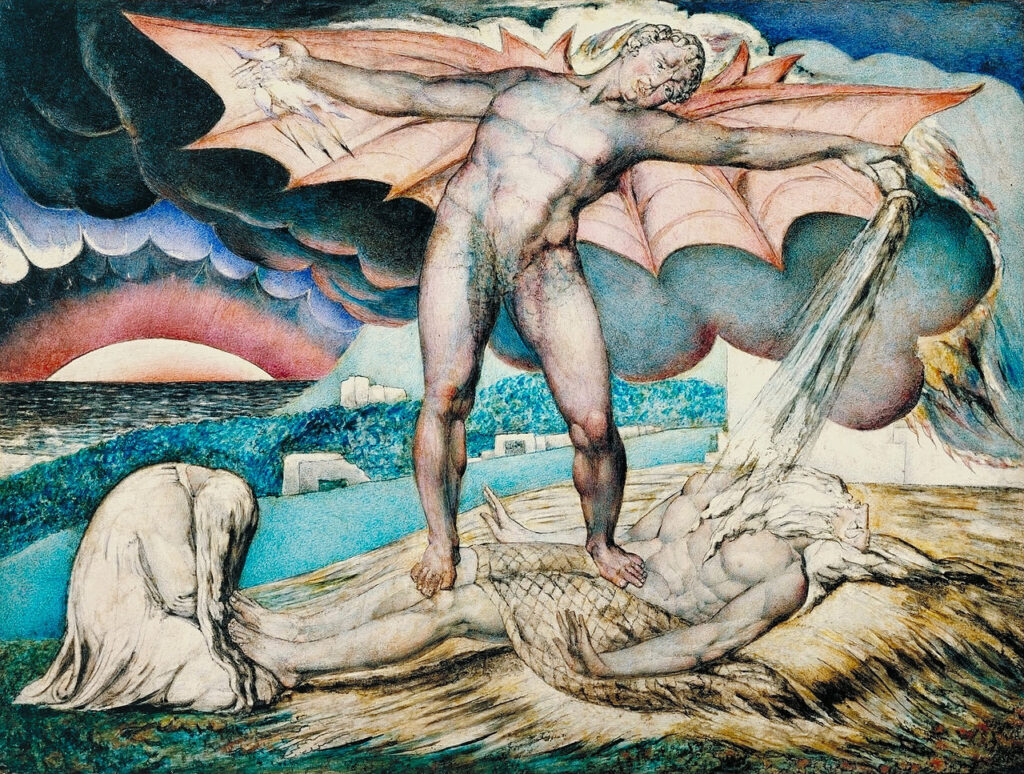

How has the individual so intent on self-mastery been so rapidly transformed into a ravenous werewolf, gorging themselves in the pale half-light?

Are these two people the same person? Can they be? They must be, yet this common scene seems to stretch the term “individual” to its limits.

If we could enter into the mind of the individual, the myth of a unified, centralised agency to which Descartes’ cogito ergo sum might apply disintegrates into a pantheon of petty selves.

This manifold nature of the inner world seems counterintuitive against our cultural backdrop of individualism, especially since the privileged role of the individual agent in Western thinking arose from the writings of Descartes.

In the human/werewolf/diet/cheesecake example, we can discern two subpersonalities which fit neatly into the Freudian division of the psyche: the higher drive — a Superego species of drive telling us what we “should do” — and the Id drive — the animal which has no understanding of ideals, but an instinct for instant gratification.

A New Way to Wisdom

The cheesecake scenario offers a simplified duality but there are many different subpersonalities at play in each of us “individuals”.

In Jungian and Nietzschean thought, the gods are something who speak through us. A god is one of those chains of thoughts that grab you and lead you to think in a certain way. This is why people can seem like hypocrites: at one moment they’re acting out of one subpersonality and another moment out of another. Multiple personalities are very much a part of each of us.

You know you can’t really get away from your drives, or gods, or subpersonalities, and so wisdom becomes not the identification of the true self but the integration of all of our selves into an effective commune, a congress where no one is leading a rebellion against the others.

The balanced psyche, then, is one in which every subpersonality is well fed at the table. Order reigns and disruption is minimised.

Sympathy for the Devils

Some people, however, get possessed by gods.

Let’s take someone like Elon Musk. When Tesla was ramping up production of the Model 3 Musk was working 120 hours a week.

He was a man possessed, with access to seemingly unnatural reserves of energy.

Take two people and tell them they now have to work 120 hours per week. What will happen in that moment? They will crumble. No one can do that without the appropriate intrinsic motivation, nor without the right neurochemistry.

It’s not about willpower. It’s something else, a different type of power; a dynamic power coming from some spirit moving through you.

The Broken Atom of Individualism

The term individual is a direct cousin of the Greek word atom — both mean indivisible. However, the term individual should be recognised as a self-contradiction, just as the atom was recognised as something other than indivisible once split by scientists in the early 20th century.

Just as cracking open the atom allowed the emergence of a brave new world of exotic forces, so too depth psychology could provide the tools to mine for a new understanding of man.

The myth of the individual blinds us to the dynamics of self-sabotage, hypocrisy, criminality and personal transformation. All these domains of human experience appear to us in a new light when viewed through the lens of the manifold internal universe of subpersonalities.

It was Nietzsche who first flagged the insight and Jung who developed it, but the revolution has remained relatively fallow. Recently, the emerging science of subpersonalities has begun to grow legs — perhaps they will take us far indeed.

Why is it that, so often, when we commit to being the best version of ourselves, we succumb to embodying a cliché, a person seemingly far from who we think we should be.

For example, a person commits to a diet. They have a vision of the person they want to be and make a commitment to reaching that desired goal.

And then, late in the night, we see that same individual — illuminated by the glow of the fridge — wolfing down cheesecake.

How has the individual so intent on self-mastery been so rapidly transformed into a ravenous werewolf, gorging themselves in the pale half-light?

Are these two people the same person? Can they be? They must be, yet this common scene seems to stretch the term “individual” to its limits.

If we could enter into the mind of the individual, the myth of a unified, centralised agency to which Descartes’ cogito ergo sum might apply disintegrates into a pantheon of petty selves.

This manifold nature of the inner world seems counterintuitive against our cultural backdrop of individualism, especially since the privileged role of the individual agent in Western thinking arose from the writings of Descartes.

In the human/werewolf/diet/cheesecake example, we can discern two subpersonalities which fit neatly into the Freudian division of the psyche: the higher drive — a Superego species of drive telling us what we “should do” — and the Id drive — the animal which has no understanding of ideals, but an instinct for instant gratification.

A New Way to Wisdom

The cheesecake scenario offers a simplified duality but there are many different subpersonalities at play in each of us “individuals”.

In Jungian and Nietzschean thought, the gods are something who speak through us. A god is one of those chains of thoughts that grab you and lead you to think in a certain way. This is why people can seem like hypocrites: at one moment they’re acting out of one subpersonality and another moment out of another. Multiple personalities are very much a part of each of us.

You know you can’t really get away from your drives, or gods, or subpersonalities, and so wisdom becomes not the identification of the true self but the integration of all of our selves into an effective commune, a congress where no one is leading a rebellion against the others.

The balanced psyche, then, is one in which every subpersonality is well fed at the table. Order reigns and disruption is minimised.

Sympathy for the Devils

Some people, however, get possessed by gods.

Let’s take someone like Elon Musk. When Tesla was ramping up production of the Model 3 Musk was working 120 hours a week.

He was a man possessed, with access to seemingly unnatural reserves of energy.

Take two people and tell them they now have to work 120 hours per week. What will happen in that moment? They will crumble. No one can do that without the appropriate intrinsic motivation, nor without the right neurochemistry.

It’s not about willpower. It’s something else, a different type of power; a dynamic power coming from some spirit moving through you.

The Broken Atom of Individualism

The term individual is a direct cousin of the Greek word atom — both mean indivisible. However, the term individual should be recognised as a self-contradiction, just as the atom was recognised as something other than indivisible once split by scientists in the early 20th century.

Just as cracking open the atom allowed the emergence of a brave new world of exotic forces, so too depth psychology could provide the tools to mine for a new understanding of man.

The myth of the individual blinds us to the dynamics of self-sabotage, hypocrisy, criminality and personal transformation. All these domains of human experience appear to us in a new light when viewed through the lens of the manifold internal universe of subpersonalities.

It was Nietzsche who first flagged the insight and Jung who developed it, but the revolution has remained relatively fallow. Recently, the emerging science of subpersonalities has begun to grow legs — perhaps they will take us far indeed.

Leave A Comment

Why is it that, so often, when we commit to being the best version of ourselves, we succumb to embodying a cliché, a person seemingly far from who we think we should be.

For example, a person commits to a diet. They have a vision of the person they want to be and make a commitment to reaching that desired goal.

And then, late in the night, we see that same individual — illuminated by the glow of the fridge — wolfing down cheesecake.

How has the individual so intent on self-mastery been so rapidly transformed into a ravenous werewolf, gorging themselves in the pale half-light?

Are these two people the same person? Can they be? They must be, yet this common scene seems to stretch the term “individual” to its limits.

If we could enter into the mind of the individual, the myth of a unified, centralised agency to which Descartes’ cogito ergo sum might apply disintegrates into a pantheon of petty selves.

This manifold nature of the inner world seems counterintuitive against our cultural backdrop of individualism, especially since the privileged role of the individual agent in Western thinking arose from the writings of Descartes.

In the human/werewolf/diet/cheesecake example, we can discern two subpersonalities which fit neatly into the Freudian division of the psyche: the higher drive — a Superego species of drive telling us what we “should do” — and the Id drive — the animal which has no understanding of ideals, but an instinct for instant gratification.

A New Way to Wisdom

The cheesecake scenario offers a simplified duality but there are many different subpersonalities at play in each of us “individuals”.

In Jungian and Nietzschean thought, the gods are something who speak through us. A god is one of those chains of thoughts that grab you and lead you to think in a certain way. This is why people can seem like hypocrites: at one moment they’re acting out of one subpersonality and another moment out of another. Multiple personalities are very much a part of each of us.

You know you can’t really get away from your drives, or gods, or subpersonalities, and so wisdom becomes not the identification of the true self but the integration of all of our selves into an effective commune, a congress where no one is leading a rebellion against the others.

The balanced psyche, then, is one in which every subpersonality is well fed at the table. Order reigns and disruption is minimised.

Sympathy for the Devils

Some people, however, get possessed by gods.

Let’s take someone like Elon Musk. When Tesla was ramping up production of the Model 3 Musk was working 120 hours a week.

He was a man possessed, with access to seemingly unnatural reserves of energy.

Take two people and tell them they now have to work 120 hours per week. What will happen in that moment? They will crumble. No one can do that without the appropriate intrinsic motivation, nor without the right neurochemistry.

It’s not about willpower. It’s something else, a different type of power; a dynamic power coming from some spirit moving through you.

The Broken Atom of Individualism

The term individual is a direct cousin of the Greek word atom — both mean indivisible. However, the term individual should be recognised as a self-contradiction, just as the atom was recognised as something other than indivisible once split by scientists in the early 20th century.

Just as cracking open the atom allowed the emergence of a brave new world of exotic forces, so too depth psychology could provide the tools to mine for a new understanding of man.

The myth of the individual blinds us to the dynamics of self-sabotage, hypocrisy, criminality and personal transformation. All these domains of human experience appear to us in a new light when viewed through the lens of the manifold internal universe of subpersonalities.

It was Nietzsche who first flagged the insight and Jung who developed it, but the revolution has remained relatively fallow. Recently, the emerging science of subpersonalities has begun to grow legs — perhaps they will take us far indeed.