I’ve often wondered why Jung was such a persona non-grata in the academy. I assumed it was because of his mystical leanings. But what I never realised is how commonly Jung was and still is considered to be an antisemite.

The charge of antisemitism is one that has been levelled at Jung since Freud published On the History of the Psychoanalytic Movement in 1914. While it may not have held much currency then, Jung’s entanglements with Nazi Germany in the years leading up to the Second World War have left a thick cloud of doubt over this question.

On the one hand we have the testimony of Jung’s many Jewish friends and confidants who unanimously attest that Jung was the furthest thing from antisemitic. On the contrary the recurring theme is that Jung connected them to their Jewish roots at a depth they had never previously known. Added to this we have the fact that Jung got a tad obsessed with the Jewish mystical school of Kabballah in his later years and it was a key part of his later work.

The dismissal of these accusations by those on this side of the argument are captured perfectly by Jung’s words in a 1949 interview (though as we will see, even the most charitable interpretation will show this statement to be false):

It must be clear to anyone who has read any of my books that I never have been a Nazi sympathizer and I never have been anti-semitic, and no amount of misquotation, mistranslation, or rearrangement of what I have written can alter the record of my true point of view.

Over against this we have the actions and words of Jung in the interwar period which have left the doubt heavy in the minds of many. One writer George Hogenson typifies this point of view in his 1983 book Jung’s Struggle with Freud where he writes that it would:

“require extraordinary, and singularly disingenuous, feats of interpretation to make [Jung’s pronouncements] into anything other than anti-Semitic pronouncements”

This is a pretty typical either/or ingroup and outgroup distinction that faces us. But this simple distinction is compounded by a couple of details. Firstly Jung commented to Rabbi Baeck — the international leader of Reform Judaism at the time — when he met him in 1946 that he had “slipped up”. And according to Kirsch in his article Jung and His Relationship to Judaism Jung privately apologised to his Jewish patients and friends including Kirsch’s father (a client and close friend of Jung’s).

So the case it seems is not a simple tale of misunderstanding. There is a story here and that is what we are going to excavate in this article. First we’ll look at the pronouncements which Hogenson says would require extraordinary feats of interpretation to make anything but antisemitic. And then we’ll look at why Jung felt the need to apologise.

The Accusations

The centre of the Jung/antisemitism storm comes down to his involvement in the 1930s with the “International General Medical Society” and its journal the Zentralblatt.

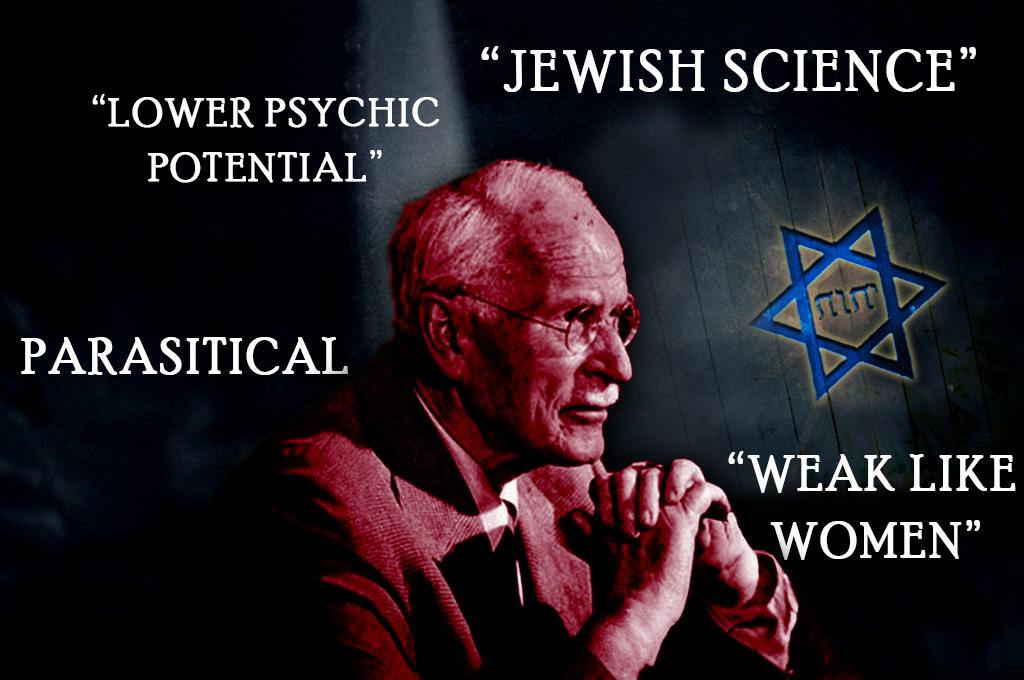

Jung’s entanglements with this society — firstly as President, then with the first publication of the society’s journal and finally with an article by Jung published in the journal in 1934 — are the basis and substance of the allegations of antisemitism against Jung. Let’s list out these accusations now and we can work our way through them in the course of the article:

- Why did Jung become President of a German society that would have to “conform” to Nazi belief? — of which Goering’s cousin was the German head

- Why was Jung’s name signed to an article mandating that every practising psychotherapist take Hitler’s Mein Kampf as a basic reference

- Did Jung claim that Freud’s school of psychoanalysis was Jewish Science

- Why did Jung say that Jewish people were:

- Completely different to Aryans

- “weak like women”

- Parasitical

- lower in psychological potential than Aryans

- Did Jung, in the Red Book say that there was a lack in the Jewish psyche compared to the Christian?

1. President of the “International General Medical Society”

The “General Medical Society” was a German organisation composed of a large group of physicians who were interested in psychotherapy but who weren’t interested in becoming part of the more Jewish Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute.

The Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute had become the first psychoanalytic training institute in 1920 and most of its members were Jewish. This was not unusual at the time. In fact it seems that the explanation for Jung’s meteoric ascent through the ranks of psychoanalysis was on account of his Gentile origins. Much to the envy of many of Freud’s Jewish followers, Jung quickly became the heir apparent of the nascent psychoanalytic movement. In a 1908 letter to Karl Abraham — the man who set up the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute and who Freud called his “best pupil” — Freud said of Jung that:

“[…] it was only by his emergence on the scene that psychoanalysis was removed from the danger of becoming a Jewish national affair.”

The General Medical Society was made up of physician-psychotherapists who were of a more conservative political nature and not interested in becoming Freudian psychoanalysts. Jung was made honorary vice-president of the society in 1931. When the Nazis came to power two years later the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute was crippled and the President of the General Medical Society resigned amid the need to “conform” the society to Nazi dogma. After this resignation Jung was asked to become president; he accepted.

The optics of this development are not good.

To the cynical this was seen as an opportunity by Jung to see his school of psychoanalysis prevail at last over Freud’s. With the effective shuttering of the Jewish Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute Jung’s would be the only show left in town.

The optics don’t get better when one learns that the infamous Reichsmarshall Herman Göring’s cousin Professor Matthias H. Göring was to become the leader of the German wing of this society.

But, on the flip side, the charitable interpretation notes that Jung only agreed to become president of the General Medical Society under certain conditions. The first being that the society become international so that it wasn’t simply a German affair but each nation would have their own group. And secondly that individuals could join without having to be part of national associations. This latter condition would allow Jewish practitioners in Germany to join — something which was otherwise cut off by their being barred from joining the German national society.

So on this first accusation we can either see Jung as an opportunist looking for his psychoanalytical model to triumph or as a pragmatist willing to risk reputational risk through entanglement with the Nazis if it allowed him to do some good for the Jewish practitioners who would have otherwise been barred from practice in Germany.

2. Promotion of Mein Kampf

All of which brings us to the second accusation: that Jung promoted Mein Kampf as required reading for psychotherapists.

This accusation arises from the first edition of the society’s publication Zentralblatt in December 1933. Göring was to be the editor of the German edition while Jung was to be the editor of the International edition. In the first international edition an editorial was published praising Nazi ideology, mandating that every practising psychotherapist take Hitler’s Mein Kampf as a basic reference and presenting Jung’s theories of archetypal cultural patterns as justification of the superiority of the Aryan race.

The optics on this, needless to say, are not very good.

But when we dig into the details what we find is that Jung wasn’t actively involved in the publishing wing of the organisation which was all being orchestrated in Germany. He was scandalised by this publication but instead of resigning he decided to let it slide. His argument was once again pragmatic: by letting this smear against his name stand he could do more good for the Jewish psychoanalysts in Germany than he could by attacking the editorial or resigning his post. As he put it:

“In this way my name unexpectedly appeared over a National Socialist manifesto, which to me personally was anything but agreeable. And yet after all—what is help or friendship that costs nothing?”

Jung inadvertently found himself entangled in politics and it’s understandable that his name has been so besmirched by this incident. But if we are to take him at his word then he willingly suffered the infamy of this undesirable connection in order to help the Jewish psychoanalysts in Germany.

The State of Psychotherapy Today (1934)

And that brings us to Jung’s article The State of Psychotherapy Today which was published a couple of months later in Zentralblatt. This one article is the primary source of the taint on Jung’s reputation and it is the source of the next five accusations.

It’s important to note that Jung himself expressed regret for this article. He later wrote to his friend (and his dentist) Dr Sigmund Hurwitz (who later became a Jungian analyst) that:

“I have written in my long life many books, and I have also written nonsense. Unfortunately, that [article] was nonsense.”

But this post-nut clarity did not immediately dawn on Jung. When this article was attacked in the Swiss media in 1934, Jung replied with a vigorous defence saying that these views were not simply signs of his hopping on the bandwagon. In this reply titled “Rejoinder to Dr Bally” Jung insisted that this was a deeply considered view that he had spoken about in 1918 and 1927.

And so in the case of this article we can’t simply dismiss it as a case of manipulation by dubious parties. These are Jung’s own words and his position on it is ambiguous. We are left wondering what exactly it is that Jung apologised for and what exactly he regretted in this article.

3. Jewish Science

Let’s look at the first accusation emerging from this article: the claim that Freud’s psychoanalytical school is Jewish Science.

The State of Psychotherapy Today consists mostly of an attack on the views of Freud and Adler (and, as Walter Kaufmann notes: in a forum they could not as Jewish people defend themselves in). About halfway through the article however we get past the theoretical differences with these other psychoanalytic founders and we come to the substantial difference between Freud and Adler on the one hand and Jung on the other: the former two are Jewish and the latter is Aryan. From there Jung dedicates a few pages to the differences between these two psychologies.

It is here that we come across the other soundbite accusations against Jung regarding the character of the Jewish psyche. The overarching point is that Freud and Adler’s psychological schools are fruits of this Jewish psychology. Consequently Jung claims that their work is a Jewish science rather than a universal one:

In my opinion it has been a grave error in medical psychology up till now to apply Jewish categories— which are not even binding on all Jews—indiscriminately to Germanic and Slavic Christendom.”

This quote in the article is a reiteration of a point he made in 1927 that:

“it is an inexcusable error to accept the conclusions of a Jewish psychology as generally valid.”

After Jung was slammed for his article in the Swiss press by a Dr Bally, Jung defended his arguments about Jewish and Aryan psychologies saying that

“Psychological differences obtain between all nations and races, and even between the inhabitants of Zurich, Basel, and Bern. (Where else would all the good jokes come from?) There are in fact differences between families and between individuals. That is why I attack every levelling psychology when it raises a claim to universal validity, as for instance the Freudian and the Adlerian. […] All branches of mankind unite in one stem—yes, but what is a stem without separate branches? Why this ridiculous touchiness when anybody dares to say anything about the psychological difference between Jews and Christians? Every child knows that differences exist.”

Jung’s attack on Freudian and Adlerian psychoanalysis as being Jewish then is akin to the more recent critiques of academic psychology. These critiques are suspicious of psychology’s claims to universality since the participants in psychological studies are predominantly university student volunteers who are paid to take part in the experiments. Or it might be compared to the pharmaceutical industry’s claims to universality coming under flack in the past five years in light of the underrepresentation of women or different ethnicities in clinical studies. Jung’s claim then can be read as being that the psychoanalysis of Freud and Adler — which was being promoted as a universal science — ignored the differences between cultures and peoples and thus was most valid for Central European Jewish people who at that time were its main practitioners as well as its main subjects of study.

This at least is the charitable reading but it is reinforced by his editorial in the December 1933 edition of the Zentralblatt — the same edition where Göring included the Nazi propaganda under Jung’s name — where Jung wrote that:

The differences which actually do exist between Germanic and Jewish psychology and which have long been known to every intelligent person are no longer to be glossed over, and this can only be beneficial to science. In psychology more than in any other science there is a “personal equation,” disregard of which falsifies the practical and theoretical findings. At the same time I should like to state expressly that this implies no depreciation of Semitic psychology, any more than it is a depreciation of the Chinese to speak of the peculiar psychology of the Oriental.

4. “Weak like women”

Now it is time to turn our attention to the specific insults Jung hurls at Jewish people in this article. And the first point might be to question this initial characterisation of these comments as insults.

When he characterises the Jewish people as being weak like women or having a lower potential psyche it seems that these comments can’t be anything but antisemitic. Given the context of Jung’s comments however and how they fit into the overall scheme of psychoanalytical literature of Freudians and Adlerians it seems that this is not necessarily antisemitic.

In contrast to the previous charges, of which I think the vast majority of people will find Jung to be innocent of antisemitism, the following charges are more of a judgement call. For some they will be antisemitic; for others they won’t.

Before we look at them in detail I would like to provide a couple of reasons why they mightn’t be read as antisemitic. The first is that the negative qualities listed above also have positive complements that Jung also discusses. They are part of a picture of a whole psychology that isn’t simply negative but nuanced.

The second reason why this might not be read as antisemitic is that Jung talks about the Aryan psychology in a similar way. And this Aryan psychology isn’t simply a glowering antithesis to the Jewish psychology but contains its own extremely negative shadings as we shall see.

If we look at Jung’s characterisations through the deconstructive lens of Jacques Derrida we see that Jung’s Binary Oppositions aren’t simply positive/Aryan vs. negative/Jewish but are more nuanced. It is not at all clear that the Jewish conception is less desirable than the Aryan one. If we see consciousness as a positive thing and animal savagery as a negative quality then we could argue the inverse.

And this is how we contextualise the comment that Jewish people are “weak like women” and also the comment that they have a lower potential psyche.

Freud and Adler have beheld very clearly the shadow that accompanies us all. The Jews have this peculiarity in common with women; being physically weaker, they have to aim at the chinks in the armour of their adversary, and thanks to this technique which has been forced on them through the centuries, the Jews themselves are best protected where others are most vulnerable. Because, again, of their civilization, more than twice as ancient as ours, they are vastly more conscious than we of human weaknesses, of the shadow-side of things, and hence in this respect much less vulnerable than we are. Thanks to their experience of an old culture, they are able, while fully conscious of their frailties, to live on friendly and even tolerant terms with them whereas we are still too young not to have “illusions” about ourselves.

So his comment that Jewish people are weak like women is a sort of backhanded insult. In the usual valuation of things consciousness is superior to unconsciousness and being in control of our psyche is better than being vulnerable to the unconscious. This is the standard hierarchy of these values and seen through this light Jung’s comments can be read by a charitable reader as complimentary to the Jewish psychology.

However the tone in which they are written seems to point in a different direction since usually the historical hierarchy of values holds manly above womanly. So there’s a bit of a mix of valuations here that is hard to tease apart. There are compliments and insults wrapped up in the same point.

This is what I meant by saying that these comments are nuanced and that some will read them as antisemitic while others will disagree.

5. Lower Potential Psyche

The next charge falls into the same category and the same conceptual frame. The consciousness of the Jewish people is already so differentiated that there is less potential for how it can unfold. As Jung puts it:

“As a member of a race with a three-thousand-year-old civilization, the Jew, like the cultured Chinese, has a wider area of psychological consciousness than we.”

This is the case with the Jewish psyche in contrast to the Aryan psyche. In contrast to the highly differentiated Jewish psychology, the Aryan psychology:

contains explosive forces and seeds of a future yet to be born, and these may not be devalued as nursery romanticism without psychic danger. The still youthful Germanic peoples are fully capable of creating new cultural forms that still lie dormant in the darkness of the unconscious of every individual – seeds bursting with energy and capable of mighty expansion

This follows on from Jung’s 1918 comparison between Jewish and Aryan psychologies where he wrote at length about this saying that:

“Christianity split the Germanic barbarian into an upper and a lower half, and enabled him, by repressing the dark side, to domesticate the brighter half and fit it for civilization. But the lower, darker half still awaits redemption and a second spell of domestication. Until then, it will remain associated with the vestiges of the prehistoric age, with the collective unconscious, which is subject to a peculiar and ever-increasing activation. As the Christian view of the world loses its authority, the more menacingly will the “blond beast” be heard prowling about in its underground prison, ready at any moment to burst out with devastating consequences. When this happens in the individual it brings about a psychological revolution, but it can also take a social form.

Jung’s belief then is that the weaker consciousness of the Aryan psychology is not strong enough (unlike the consciousness of Jewish psychology) to hold back the deluge of energy from the collective unconscious. The wilder unconscious of the barbarian Germanic psychology prowls its underground prison “ready at any moment to burst out with devastating consequences”.

Again we can read this two different ways. Firstly we can see higher potential as being the superior in the value hierarchy of higher vs lower psychic potential. Or we can see this possibility of savagery as being the lower in the classical hierarchy of civilised vs barbarian or even as less vs more developed. If we reframe this as a child vs. an adult it takes on a different aspect — the adult has less potential insofar as much of their potential has already been realised. The clarity of this is muddled by the language that Jung uses which is not harmless as we’ll see in the section on his apology.

Once again we are faced here with the need for a personal judgement call when it comes to the charge of antisemitism. As noted earlier, the point of this article isn’t to proclaim a final judgement but to lay out the facts in the most balanced way possible.

6. Parasitical

There remains one final charge that has been addressed to Jung from this 1934 article and that is the idea that Jewish psychology requires a host nation and has produced no cultural forms of its own.

In this article he writes that:

“The Jew, who is something of a nomad, has never yet created a cultural form of his own and as far as we can see never will, since all his instincts and talents require a more or less civilized nation to act as host for their development.”

By cultural form here Jung seems to mean a society.

In their letters to Jung, his close friends and associates Kirsch and Neumann — writing from Palestine in the 1930s in what would later become the Jewish state of Israel — disputed this belief of Jung’s. They claim that while his comments may be true of the Jewish exiles it does not speak to the Jewish people who were setting down roots in the ancient homeland. Jung wasn’t immediately convinced and he wrote to Neumann saying:

“Even Moses Maimonides preferred Cairo, though he could live in Jerusalem. Can it be that the Jew is so very used to being not a Jew, that he needs the Palestinian soil in concreto in order to be reminded of being Jewish?” (Neumann 2002, 80).

In time Jung writes to Kirsch saying that he is open to the possibility that Palestine may change his mind about this part of Jewish psychology.

This comment has been received by many as Jung calling Jewish people parasites requiring a host nation to sustain them. They cannot form their own independent society. This is a bizarre claim and one that has surely been disproven by the history of Israel.

7. The Red Book

That is everything we can say about this 1934 article which is the basis of Jung’s lasting reputation as an antisemite. But it is not the only source. Long before the rise of National Socialism, Jung wrote what is now known as the Red Book. This book was based on a series of visions Jung had between November 1913 and April 1918.

The second section of this book begins with an inner dialogue between Jung’s dream ego and a figure he calls the “Red One”. In the vision Jung’s dream ego converses with a red knight. In the course of this dialogue Jung says everyone should carry Christ in his or her heart. When the Red One says there are also Jews who are good people without having need for the Christian Gospels, the dialogue then proceeds as follows: Jung’s dream ego:

“Jews lack something—one in his head, another in his heart, and he himself feels as if he lacks something”

The Red One responds,

“Indeed I am no Jew, but I must come to the Jew’s defense; you seem to be a Jew hater?”

Here Jung’s dream ego responds:

“Well now you speak like all those Jews who accuse anyone of Jew hating who does not have a completely favorable judgment while they make the bloodiest jokes about their own kind. Since the Jews only too clearly feel that particular lack and yet do not want to admit it, they are extremely sensitive to criticism. Do you believe that Christianity left no mark on the souls of men? And do you believe that one who has not experienced this most intimately can still partake of its fruit?”

There’s not much that can be offered by way of defence of this comment. To my eyes this is antisemitic through and through. And not just antisemitic. Jung’s frame assumes that Christian cultures are superior to all other world cultures — unless perhaps we exclude Islam which has not only Jesus but also Muhammad so perhaps a similar claim could be made there. And it seems to be a view that the later Jung might disagree with given his later fascination with the Jewish mystical school of Kabballah. Once again there is no black-and-white answer to this question and each must evaluate for themselves.

Why Apologise

Having looked at the critical and charitable interpretations of Jung’s words we still have to square the charitable interpretations of Jung’s apologists with the matter of Jung’s apology. In the Rejoinder to Dr Bally written shortly after the 1934 article he defended his position on Jewish psychology as one he had held publicly since 1918. Why then apologise later and call the article “nonsense”? If he was a big help to the anti-Nazi war movement and to numerous Jewish people in the Second World War then why would he later say he “slipped up”?

In the meeting with Rabbi Baeck where he made this confession Jung said it was his Nazi sympathies that were at the root of his apology. He “stumbled” in connection with Nazism and his expectations that maybe something great would burst forth there. Jung had been hoping for a new cultural form that would bring a new value structure to the world.

Such was Jung’s enthusiasm for this possibility that apparently he would have voted for Hitler had he lived in Germany. This at least was what Kirsch was told by Toni Wolff — Jung’s mistress — at a conference in Switzerland.

It’s important to remember the greater context of Jung’s work; following on from Nietzsche he was well aware of the meaning crisis of Nihilism and the need for a new tablet of values to emerge. He believed that this must emerge from the collective unconscious and it seemed that the Germanic Aryan psychology was ripe to be the birthplace of that new tablet of values. The Jewish psyche couldn’t be the womb of it since it was already too civilised and too conscious. Jung’s apology then isn’t about bias against the Jewish psyche so much as it was a bias towards the Aryan psyche and the excitement that something monolithic and revitalising might be born from this primal “underground prison”.

This might explain the confusing valuations in Jung’s 1934 article. His fascination with the collective unconscious led him to value the potential of the wild Aryan unconscious above the civilised Jewish consciousness. When the reality of Nazi Germany dawned on him, Jung sobered up and repented of his enthusiasm.

From this then we see that Jung’s apology stemmed not from a dislike of Jewish psyche but for an enthusiasm and hope for the Aryan psyche. He was apologising for the naivete which left him hopeful rather than terrified by the energy in Germany. His apology then is not about antisemitism but about Nazi-sympathising.

Throughout this time he was friendly and supportive of Jewish people. Hence the comments of his friends and clients. And when the Nazis began to turn more publicly on Jewish people Jung used his means to help as many as he could. And this wasn’t the only way he helped.

Many years after the war, it emerged that Jung was working as a spy for the precursor to the CIA — the Office of Strategic Services. Jung wrote psychological analyses of Nazi leaders which were read by Eisenhower. The CIA’s first civil director Allen W. Dulles, who was Jung’s handler during the war, commented that:

“Nobody will probably ever know how much Professor Jung contributed to the Allied cause during the war.”

All of this combined with Jung’s fascination in later years with the Jewish mystical philosophy Kabballah and the number of Jewish friends and clients in his immediate circle must lead us to believe that ultimately Jung was far from a hater of Jewish people or Jewish culture. He may have had some questionable views through the years and said some questionable things but it would be a stretch to lump him in with the antisemitism of the Nazis or other antisemitic individuals and groups then or now. If we compare these accusations of antisemitism towards Jung and those towards Heidegger with his lifelong belief in a conspiracy of the “world Jewry” a very stark contrast emerges.

Not all will find Jung innocent but all will be forced to admit that it is a nuanced case and this is not the simple story of a man who hated Jewish people.

Sources:

- Cohen B (2012) Jung’s Answer to Jews. Jung Journal 6(1): 56–71.

- Goggin JE and Goggin EB (2001) Death of a ‘Jewish Science’: Psychoanalysis in the Third Reich. West Lafayette, Ind: Purdue University Press.

- Jung, C. (2014) After the Catastrophe in: Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 10: Civilization in Transition. edited by RFC Hull Princeton University Press, pp. 194–217. Available at: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9781400850976.194/html (accessed 13 January 2024).

- Jung, C. (2014) The State of Psychotherapy Today in: Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 10: Civilization in Transition. edited by RFC Hull Princeton University Press, pp. 157–174. Available at: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9781400850976.157/html (accessed 14 August 2023).

- Kaufmann W (2003) Discovering the Mind. Vol. 3: Freud, Adler, and Jung / Walter Kaufmann. 3. print. New Brunswick: Transaction Publ.

- Kirsch T (2012) Jung and His Relationship to Judaism. Jung Journal 6(1): 10–20.

- Samuels A (1994) Jung and antisemitism. Jewish Quarterly 41(1). Routledge: 59–63.

I’ve often wondered why Jung was such a persona non-grata in the academy. I assumed it was because of his mystical leanings. But what I never realised is how commonly Jung was and still is considered to be an antisemite.

The charge of antisemitism is one that has been levelled at Jung since Freud published On the History of the Psychoanalytic Movement in 1914. While it may not have held much currency then, Jung’s entanglements with Nazi Germany in the years leading up to the Second World War have left a thick cloud of doubt over this question.

On the one hand we have the testimony of Jung’s many Jewish friends and confidants who unanimously attest that Jung was the furthest thing from antisemitic. On the contrary the recurring theme is that Jung connected them to their Jewish roots at a depth they had never previously known. Added to this we have the fact that Jung got a tad obsessed with the Jewish mystical school of Kabballah in his later years and it was a key part of his later work.

The dismissal of these accusations by those on this side of the argument are captured perfectly by Jung’s words in a 1949 interview (though as we will see, even the most charitable interpretation will show this statement to be false):

It must be clear to anyone who has read any of my books that I never have been a Nazi sympathizer and I never have been anti-semitic, and no amount of misquotation, mistranslation, or rearrangement of what I have written can alter the record of my true point of view.

Over against this we have the actions and words of Jung in the interwar period which have left the doubt heavy in the minds of many. One writer George Hogenson typifies this point of view in his 1983 book Jung’s Struggle with Freud where he writes that it would:

“require extraordinary, and singularly disingenuous, feats of interpretation to make [Jung’s pronouncements] into anything other than anti-Semitic pronouncements”

This is a pretty typical either/or ingroup and outgroup distinction that faces us. But this simple distinction is compounded by a couple of details. Firstly Jung commented to Rabbi Baeck — the international leader of Reform Judaism at the time — when he met him in 1946 that he had “slipped up”. And according to Kirsch in his article Jung and His Relationship to Judaism Jung privately apologised to his Jewish patients and friends including Kirsch’s father (a client and close friend of Jung’s).

So the case it seems is not a simple tale of misunderstanding. There is a story here and that is what we are going to excavate in this article. First we’ll look at the pronouncements which Hogenson says would require extraordinary feats of interpretation to make anything but antisemitic. And then we’ll look at why Jung felt the need to apologise.

The Accusations

The centre of the Jung/antisemitism storm comes down to his involvement in the 1930s with the “International General Medical Society” and its journal the Zentralblatt.

Jung’s entanglements with this society — firstly as President, then with the first publication of the society’s journal and finally with an article by Jung published in the journal in 1934 — are the basis and substance of the allegations of antisemitism against Jung. Let’s list out these accusations now and we can work our way through them in the course of the article:

- Why did Jung become President of a German society that would have to “conform” to Nazi belief? — of which Goering’s cousin was the German head

- Why was Jung’s name signed to an article mandating that every practising psychotherapist take Hitler’s Mein Kampf as a basic reference

- Did Jung claim that Freud’s school of psychoanalysis was Jewish Science

- Why did Jung say that Jewish people were:

- Completely different to Aryans

- “weak like women”

- Parasitical

- lower in psychological potential than Aryans

- Did Jung, in the Red Book say that there was a lack in the Jewish psyche compared to the Christian?

1. President of the “International General Medical Society”

The “General Medical Society” was a German organisation composed of a large group of physicians who were interested in psychotherapy but who weren’t interested in becoming part of the more Jewish Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute.

The Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute had become the first psychoanalytic training institute in 1920 and most of its members were Jewish. This was not unusual at the time. In fact it seems that the explanation for Jung’s meteoric ascent through the ranks of psychoanalysis was on account of his Gentile origins. Much to the envy of many of Freud’s Jewish followers, Jung quickly became the heir apparent of the nascent psychoanalytic movement. In a 1908 letter to Karl Abraham — the man who set up the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute and who Freud called his “best pupil” — Freud said of Jung that:

“[…] it was only by his emergence on the scene that psychoanalysis was removed from the danger of becoming a Jewish national affair.”

The General Medical Society was made up of physician-psychotherapists who were of a more conservative political nature and not interested in becoming Freudian psychoanalysts. Jung was made honorary vice-president of the society in 1931. When the Nazis came to power two years later the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute was crippled and the President of the General Medical Society resigned amid the need to “conform” the society to Nazi dogma. After this resignation Jung was asked to become president; he accepted.

The optics of this development are not good.

To the cynical this was seen as an opportunity by Jung to see his school of psychoanalysis prevail at last over Freud’s. With the effective shuttering of the Jewish Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute Jung’s would be the only show left in town.

The optics don’t get better when one learns that the infamous Reichsmarshall Herman Göring’s cousin Professor Matthias H. Göring was to become the leader of the German wing of this society.

But, on the flip side, the charitable interpretation notes that Jung only agreed to become president of the General Medical Society under certain conditions. The first being that the society become international so that it wasn’t simply a German affair but each nation would have their own group. And secondly that individuals could join without having to be part of national associations. This latter condition would allow Jewish practitioners in Germany to join — something which was otherwise cut off by their being barred from joining the German national society.

So on this first accusation we can either see Jung as an opportunist looking for his psychoanalytical model to triumph or as a pragmatist willing to risk reputational risk through entanglement with the Nazis if it allowed him to do some good for the Jewish practitioners who would have otherwise been barred from practice in Germany.

2. Promotion of Mein Kampf

All of which brings us to the second accusation: that Jung promoted Mein Kampf as required reading for psychotherapists.

This accusation arises from the first edition of the society’s publication Zentralblatt in December 1933. Göring was to be the editor of the German edition while Jung was to be the editor of the International edition. In the first international edition an editorial was published praising Nazi ideology, mandating that every practising psychotherapist take Hitler’s Mein Kampf as a basic reference and presenting Jung’s theories of archetypal cultural patterns as justification of the superiority of the Aryan race.

The optics on this, needless to say, are not very good.

But when we dig into the details what we find is that Jung wasn’t actively involved in the publishing wing of the organisation which was all being orchestrated in Germany. He was scandalised by this publication but instead of resigning he decided to let it slide. His argument was once again pragmatic: by letting this smear against his name stand he could do more good for the Jewish psychoanalysts in Germany than he could by attacking the editorial or resigning his post. As he put it:

“In this way my name unexpectedly appeared over a National Socialist manifesto, which to me personally was anything but agreeable. And yet after all—what is help or friendship that costs nothing?”

Jung inadvertently found himself entangled in politics and it’s understandable that his name has been so besmirched by this incident. But if we are to take him at his word then he willingly suffered the infamy of this undesirable connection in order to help the Jewish psychoanalysts in Germany.

The State of Psychotherapy Today (1934)

And that brings us to Jung’s article The State of Psychotherapy Today which was published a couple of months later in Zentralblatt. This one article is the primary source of the taint on Jung’s reputation and it is the source of the next five accusations.

It’s important to note that Jung himself expressed regret for this article. He later wrote to his friend (and his dentist) Dr Sigmund Hurwitz (who later became a Jungian analyst) that:

“I have written in my long life many books, and I have also written nonsense. Unfortunately, that [article] was nonsense.”

But this post-nut clarity did not immediately dawn on Jung. When this article was attacked in the Swiss media in 1934, Jung replied with a vigorous defence saying that these views were not simply signs of his hopping on the bandwagon. In this reply titled “Rejoinder to Dr Bally” Jung insisted that this was a deeply considered view that he had spoken about in 1918 and 1927.

And so in the case of this article we can’t simply dismiss it as a case of manipulation by dubious parties. These are Jung’s own words and his position on it is ambiguous. We are left wondering what exactly it is that Jung apologised for and what exactly he regretted in this article.

3. Jewish Science

Let’s look at the first accusation emerging from this article: the claim that Freud’s psychoanalytical school is Jewish Science.

The State of Psychotherapy Today consists mostly of an attack on the views of Freud and Adler (and, as Walter Kaufmann notes: in a forum they could not as Jewish people defend themselves in). About halfway through the article however we get past the theoretical differences with these other psychoanalytic founders and we come to the substantial difference between Freud and Adler on the one hand and Jung on the other: the former two are Jewish and the latter is Aryan. From there Jung dedicates a few pages to the differences between these two psychologies.

It is here that we come across the other soundbite accusations against Jung regarding the character of the Jewish psyche. The overarching point is that Freud and Adler’s psychological schools are fruits of this Jewish psychology. Consequently Jung claims that their work is a Jewish science rather than a universal one:

In my opinion it has been a grave error in medical psychology up till now to apply Jewish categories— which are not even binding on all Jews—indiscriminately to Germanic and Slavic Christendom.”

This quote in the article is a reiteration of a point he made in 1927 that:

“it is an inexcusable error to accept the conclusions of a Jewish psychology as generally valid.”

After Jung was slammed for his article in the Swiss press by a Dr Bally, Jung defended his arguments about Jewish and Aryan psychologies saying that

“Psychological differences obtain between all nations and races, and even between the inhabitants of Zurich, Basel, and Bern. (Where else would all the good jokes come from?) There are in fact differences between families and between individuals. That is why I attack every levelling psychology when it raises a claim to universal validity, as for instance the Freudian and the Adlerian. […] All branches of mankind unite in one stem—yes, but what is a stem without separate branches? Why this ridiculous touchiness when anybody dares to say anything about the psychological difference between Jews and Christians? Every child knows that differences exist.”

Jung’s attack on Freudian and Adlerian psychoanalysis as being Jewish then is akin to the more recent critiques of academic psychology. These critiques are suspicious of psychology’s claims to universality since the participants in psychological studies are predominantly university student volunteers who are paid to take part in the experiments. Or it might be compared to the pharmaceutical industry’s claims to universality coming under flack in the past five years in light of the underrepresentation of women or different ethnicities in clinical studies. Jung’s claim then can be read as being that the psychoanalysis of Freud and Adler — which was being promoted as a universal science — ignored the differences between cultures and peoples and thus was most valid for Central European Jewish people who at that time were its main practitioners as well as its main subjects of study.

This at least is the charitable reading but it is reinforced by his editorial in the December 1933 edition of the Zentralblatt — the same edition where Göring included the Nazi propaganda under Jung’s name — where Jung wrote that:

The differences which actually do exist between Germanic and Jewish psychology and which have long been known to every intelligent person are no longer to be glossed over, and this can only be beneficial to science. In psychology more than in any other science there is a “personal equation,” disregard of which falsifies the practical and theoretical findings. At the same time I should like to state expressly that this implies no depreciation of Semitic psychology, any more than it is a depreciation of the Chinese to speak of the peculiar psychology of the Oriental.

4. “Weak like women”

Now it is time to turn our attention to the specific insults Jung hurls at Jewish people in this article. And the first point might be to question this initial characterisation of these comments as insults.

When he characterises the Jewish people as being weak like women or having a lower potential psyche it seems that these comments can’t be anything but antisemitic. Given the context of Jung’s comments however and how they fit into the overall scheme of psychoanalytical literature of Freudians and Adlerians it seems that this is not necessarily antisemitic.

In contrast to the previous charges, of which I think the vast majority of people will find Jung to be innocent of antisemitism, the following charges are more of a judgement call. For some they will be antisemitic; for others they won’t.

Before we look at them in detail I would like to provide a couple of reasons why they mightn’t be read as antisemitic. The first is that the negative qualities listed above also have positive complements that Jung also discusses. They are part of a picture of a whole psychology that isn’t simply negative but nuanced.

The second reason why this might not be read as antisemitic is that Jung talks about the Aryan psychology in a similar way. And this Aryan psychology isn’t simply a glowering antithesis to the Jewish psychology but contains its own extremely negative shadings as we shall see.

If we look at Jung’s characterisations through the deconstructive lens of Jacques Derrida we see that Jung’s Binary Oppositions aren’t simply positive/Aryan vs. negative/Jewish but are more nuanced. It is not at all clear that the Jewish conception is less desirable than the Aryan one. If we see consciousness as a positive thing and animal savagery as a negative quality then we could argue the inverse.

And this is how we contextualise the comment that Jewish people are “weak like women” and also the comment that they have a lower potential psyche.

Freud and Adler have beheld very clearly the shadow that accompanies us all. The Jews have this peculiarity in common with women; being physically weaker, they have to aim at the chinks in the armour of their adversary, and thanks to this technique which has been forced on them through the centuries, the Jews themselves are best protected where others are most vulnerable. Because, again, of their civilization, more than twice as ancient as ours, they are vastly more conscious than we of human weaknesses, of the shadow-side of things, and hence in this respect much less vulnerable than we are. Thanks to their experience of an old culture, they are able, while fully conscious of their frailties, to live on friendly and even tolerant terms with them whereas we are still too young not to have “illusions” about ourselves.

So his comment that Jewish people are weak like women is a sort of backhanded insult. In the usual valuation of things consciousness is superior to unconsciousness and being in control of our psyche is better than being vulnerable to the unconscious. This is the standard hierarchy of these values and seen through this light Jung’s comments can be read by a charitable reader as complimentary to the Jewish psychology.

However the tone in which they are written seems to point in a different direction since usually the historical hierarchy of values holds manly above womanly. So there’s a bit of a mix of valuations here that is hard to tease apart. There are compliments and insults wrapped up in the same point.

This is what I meant by saying that these comments are nuanced and that some will read them as antisemitic while others will disagree.

5. Lower Potential Psyche

The next charge falls into the same category and the same conceptual frame. The consciousness of the Jewish people is already so differentiated that there is less potential for how it can unfold. As Jung puts it:

“As a member of a race with a three-thousand-year-old civilization, the Jew, like the cultured Chinese, has a wider area of psychological consciousness than we.”

This is the case with the Jewish psyche in contrast to the Aryan psyche. In contrast to the highly differentiated Jewish psychology, the Aryan psychology:

contains explosive forces and seeds of a future yet to be born, and these may not be devalued as nursery romanticism without psychic danger. The still youthful Germanic peoples are fully capable of creating new cultural forms that still lie dormant in the darkness of the unconscious of every individual – seeds bursting with energy and capable of mighty expansion

This follows on from Jung’s 1918 comparison between Jewish and Aryan psychologies where he wrote at length about this saying that:

“Christianity split the Germanic barbarian into an upper and a lower half, and enabled him, by repressing the dark side, to domesticate the brighter half and fit it for civilization. But the lower, darker half still awaits redemption and a second spell of domestication. Until then, it will remain associated with the vestiges of the prehistoric age, with the collective unconscious, which is subject to a peculiar and ever-increasing activation. As the Christian view of the world loses its authority, the more menacingly will the “blond beast” be heard prowling about in its underground prison, ready at any moment to burst out with devastating consequences. When this happens in the individual it brings about a psychological revolution, but it can also take a social form.

Jung’s belief then is that the weaker consciousness of the Aryan psychology is not strong enough (unlike the consciousness of Jewish psychology) to hold back the deluge of energy from the collective unconscious. The wilder unconscious of the barbarian Germanic psychology prowls its underground prison “ready at any moment to burst out with devastating consequences”.

Again we can read this two different ways. Firstly we can see higher potential as being the superior in the value hierarchy of higher vs lower psychic potential. Or we can see this possibility of savagery as being the lower in the classical hierarchy of civilised vs barbarian or even as less vs more developed. If we reframe this as a child vs. an adult it takes on a different aspect — the adult has less potential insofar as much of their potential has already been realised. The clarity of this is muddled by the language that Jung uses which is not harmless as we’ll see in the section on his apology.

Once again we are faced here with the need for a personal judgement call when it comes to the charge of antisemitism. As noted earlier, the point of this article isn’t to proclaim a final judgement but to lay out the facts in the most balanced way possible.

6. Parasitical

There remains one final charge that has been addressed to Jung from this 1934 article and that is the idea that Jewish psychology requires a host nation and has produced no cultural forms of its own.

In this article he writes that:

“The Jew, who is something of a nomad, has never yet created a cultural form of his own and as far as we can see never will, since all his instincts and talents require a more or less civilized nation to act as host for their development.”

By cultural form here Jung seems to mean a society.

In their letters to Jung, his close friends and associates Kirsch and Neumann — writing from Palestine in the 1930s in what would later become the Jewish state of Israel — disputed this belief of Jung’s. They claim that while his comments may be true of the Jewish exiles it does not speak to the Jewish people who were setting down roots in the ancient homeland. Jung wasn’t immediately convinced and he wrote to Neumann saying:

“Even Moses Maimonides preferred Cairo, though he could live in Jerusalem. Can it be that the Jew is so very used to being not a Jew, that he needs the Palestinian soil in concreto in order to be reminded of being Jewish?” (Neumann 2002, 80).

In time Jung writes to Kirsch saying that he is open to the possibility that Palestine may change his mind about this part of Jewish psychology.

This comment has been received by many as Jung calling Jewish people parasites requiring a host nation to sustain them. They cannot form their own independent society. This is a bizarre claim and one that has surely been disproven by the history of Israel.

7. The Red Book

That is everything we can say about this 1934 article which is the basis of Jung’s lasting reputation as an antisemite. But it is not the only source. Long before the rise of National Socialism, Jung wrote what is now known as the Red Book. This book was based on a series of visions Jung had between November 1913 and April 1918.

The second section of this book begins with an inner dialogue between Jung’s dream ego and a figure he calls the “Red One”. In the vision Jung’s dream ego converses with a red knight. In the course of this dialogue Jung says everyone should carry Christ in his or her heart. When the Red One says there are also Jews who are good people without having need for the Christian Gospels, the dialogue then proceeds as follows: Jung’s dream ego:

“Jews lack something—one in his head, another in his heart, and he himself feels as if he lacks something”

The Red One responds,

“Indeed I am no Jew, but I must come to the Jew’s defense; you seem to be a Jew hater?”

Here Jung’s dream ego responds:

“Well now you speak like all those Jews who accuse anyone of Jew hating who does not have a completely favorable judgment while they make the bloodiest jokes about their own kind. Since the Jews only too clearly feel that particular lack and yet do not want to admit it, they are extremely sensitive to criticism. Do you believe that Christianity left no mark on the souls of men? And do you believe that one who has not experienced this most intimately can still partake of its fruit?”

There’s not much that can be offered by way of defence of this comment. To my eyes this is antisemitic through and through. And not just antisemitic. Jung’s frame assumes that Christian cultures are superior to all other world cultures — unless perhaps we exclude Islam which has not only Jesus but also Muhammad so perhaps a similar claim could be made there. And it seems to be a view that the later Jung might disagree with given his later fascination with the Jewish mystical school of Kabballah. Once again there is no black-and-white answer to this question and each must evaluate for themselves.

Why Apologise

Having looked at the critical and charitable interpretations of Jung’s words we still have to square the charitable interpretations of Jung’s apologists with the matter of Jung’s apology. In the Rejoinder to Dr Bally written shortly after the 1934 article he defended his position on Jewish psychology as one he had held publicly since 1918. Why then apologise later and call the article “nonsense”? If he was a big help to the anti-Nazi war movement and to numerous Jewish people in the Second World War then why would he later say he “slipped up”?

In the meeting with Rabbi Baeck where he made this confession Jung said it was his Nazi sympathies that were at the root of his apology. He “stumbled” in connection with Nazism and his expectations that maybe something great would burst forth there. Jung had been hoping for a new cultural form that would bring a new value structure to the world.

Such was Jung’s enthusiasm for this possibility that apparently he would have voted for Hitler had he lived in Germany. This at least was what Kirsch was told by Toni Wolff — Jung’s mistress — at a conference in Switzerland.

It’s important to remember the greater context of Jung’s work; following on from Nietzsche he was well aware of the meaning crisis of Nihilism and the need for a new tablet of values to emerge. He believed that this must emerge from the collective unconscious and it seemed that the Germanic Aryan psychology was ripe to be the birthplace of that new tablet of values. The Jewish psyche couldn’t be the womb of it since it was already too civilised and too conscious. Jung’s apology then isn’t about bias against the Jewish psyche so much as it was a bias towards the Aryan psyche and the excitement that something monolithic and revitalising might be born from this primal “underground prison”.

This might explain the confusing valuations in Jung’s 1934 article. His fascination with the collective unconscious led him to value the potential of the wild Aryan unconscious above the civilised Jewish consciousness. When the reality of Nazi Germany dawned on him, Jung sobered up and repented of his enthusiasm.

From this then we see that Jung’s apology stemmed not from a dislike of Jewish psyche but for an enthusiasm and hope for the Aryan psyche. He was apologising for the naivete which left him hopeful rather than terrified by the energy in Germany. His apology then is not about antisemitism but about Nazi-sympathising.

Throughout this time he was friendly and supportive of Jewish people. Hence the comments of his friends and clients. And when the Nazis began to turn more publicly on Jewish people Jung used his means to help as many as he could. And this wasn’t the only way he helped.

Many years after the war, it emerged that Jung was working as a spy for the precursor to the CIA — the Office of Strategic Services. Jung wrote psychological analyses of Nazi leaders which were read by Eisenhower. The CIA’s first civil director Allen W. Dulles, who was Jung’s handler during the war, commented that:

“Nobody will probably ever know how much Professor Jung contributed to the Allied cause during the war.”

All of this combined with Jung’s fascination in later years with the Jewish mystical philosophy Kabballah and the number of Jewish friends and clients in his immediate circle must lead us to believe that ultimately Jung was far from a hater of Jewish people or Jewish culture. He may have had some questionable views through the years and said some questionable things but it would be a stretch to lump him in with the antisemitism of the Nazis or other antisemitic individuals and groups then or now. If we compare these accusations of antisemitism towards Jung and those towards Heidegger with his lifelong belief in a conspiracy of the “world Jewry” a very stark contrast emerges.

Not all will find Jung innocent but all will be forced to admit that it is a nuanced case and this is not the simple story of a man who hated Jewish people.

Sources:

- Cohen B (2012) Jung’s Answer to Jews. Jung Journal 6(1): 56–71.

- Goggin JE and Goggin EB (2001) Death of a ‘Jewish Science’: Psychoanalysis in the Third Reich. West Lafayette, Ind: Purdue University Press.

- Jung, C. (2014) After the Catastrophe in: Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 10: Civilization in Transition. edited by RFC Hull Princeton University Press, pp. 194–217. Available at: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9781400850976.194/html (accessed 13 January 2024).

- Jung, C. (2014) The State of Psychotherapy Today in: Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 10: Civilization in Transition. edited by RFC Hull Princeton University Press, pp. 157–174. Available at: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9781400850976.157/html (accessed 14 August 2023).

- Kaufmann W (2003) Discovering the Mind. Vol. 3: Freud, Adler, and Jung / Walter Kaufmann. 3. print. New Brunswick: Transaction Publ.

- Kirsch T (2012) Jung and His Relationship to Judaism. Jung Journal 6(1): 10–20.

- Samuels A (1994) Jung and antisemitism. Jewish Quarterly 41(1). Routledge: 59–63.

Leave A Comment

I’ve often wondered why Jung was such a persona non-grata in the academy. I assumed it was because of his mystical leanings. But what I never realised is how commonly Jung was and still is considered to be an antisemite.

The charge of antisemitism is one that has been levelled at Jung since Freud published On the History of the Psychoanalytic Movement in 1914. While it may not have held much currency then, Jung’s entanglements with Nazi Germany in the years leading up to the Second World War have left a thick cloud of doubt over this question.

On the one hand we have the testimony of Jung’s many Jewish friends and confidants who unanimously attest that Jung was the furthest thing from antisemitic. On the contrary the recurring theme is that Jung connected them to their Jewish roots at a depth they had never previously known. Added to this we have the fact that Jung got a tad obsessed with the Jewish mystical school of Kabballah in his later years and it was a key part of his later work.

The dismissal of these accusations by those on this side of the argument are captured perfectly by Jung’s words in a 1949 interview (though as we will see, even the most charitable interpretation will show this statement to be false):

It must be clear to anyone who has read any of my books that I never have been a Nazi sympathizer and I never have been anti-semitic, and no amount of misquotation, mistranslation, or rearrangement of what I have written can alter the record of my true point of view.

Over against this we have the actions and words of Jung in the interwar period which have left the doubt heavy in the minds of many. One writer George Hogenson typifies this point of view in his 1983 book Jung’s Struggle with Freud where he writes that it would:

“require extraordinary, and singularly disingenuous, feats of interpretation to make [Jung’s pronouncements] into anything other than anti-Semitic pronouncements”

This is a pretty typical either/or ingroup and outgroup distinction that faces us. But this simple distinction is compounded by a couple of details. Firstly Jung commented to Rabbi Baeck — the international leader of Reform Judaism at the time — when he met him in 1946 that he had “slipped up”. And according to Kirsch in his article Jung and His Relationship to Judaism Jung privately apologised to his Jewish patients and friends including Kirsch’s father (a client and close friend of Jung’s).

So the case it seems is not a simple tale of misunderstanding. There is a story here and that is what we are going to excavate in this article. First we’ll look at the pronouncements which Hogenson says would require extraordinary feats of interpretation to make anything but antisemitic. And then we’ll look at why Jung felt the need to apologise.

The Accusations

The centre of the Jung/antisemitism storm comes down to his involvement in the 1930s with the “International General Medical Society” and its journal the Zentralblatt.

Jung’s entanglements with this society — firstly as President, then with the first publication of the society’s journal and finally with an article by Jung published in the journal in 1934 — are the basis and substance of the allegations of antisemitism against Jung. Let’s list out these accusations now and we can work our way through them in the course of the article:

- Why did Jung become President of a German society that would have to “conform” to Nazi belief? — of which Goering’s cousin was the German head

- Why was Jung’s name signed to an article mandating that every practising psychotherapist take Hitler’s Mein Kampf as a basic reference

- Did Jung claim that Freud’s school of psychoanalysis was Jewish Science

- Why did Jung say that Jewish people were:

- Completely different to Aryans

- “weak like women”

- Parasitical

- lower in psychological potential than Aryans

- Did Jung, in the Red Book say that there was a lack in the Jewish psyche compared to the Christian?

1. President of the “International General Medical Society”

The “General Medical Society” was a German organisation composed of a large group of physicians who were interested in psychotherapy but who weren’t interested in becoming part of the more Jewish Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute.

The Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute had become the first psychoanalytic training institute in 1920 and most of its members were Jewish. This was not unusual at the time. In fact it seems that the explanation for Jung’s meteoric ascent through the ranks of psychoanalysis was on account of his Gentile origins. Much to the envy of many of Freud’s Jewish followers, Jung quickly became the heir apparent of the nascent psychoanalytic movement. In a 1908 letter to Karl Abraham — the man who set up the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute and who Freud called his “best pupil” — Freud said of Jung that:

“[…] it was only by his emergence on the scene that psychoanalysis was removed from the danger of becoming a Jewish national affair.”

The General Medical Society was made up of physician-psychotherapists who were of a more conservative political nature and not interested in becoming Freudian psychoanalysts. Jung was made honorary vice-president of the society in 1931. When the Nazis came to power two years later the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute was crippled and the President of the General Medical Society resigned amid the need to “conform” the society to Nazi dogma. After this resignation Jung was asked to become president; he accepted.

The optics of this development are not good.

To the cynical this was seen as an opportunity by Jung to see his school of psychoanalysis prevail at last over Freud’s. With the effective shuttering of the Jewish Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute Jung’s would be the only show left in town.

The optics don’t get better when one learns that the infamous Reichsmarshall Herman Göring’s cousin Professor Matthias H. Göring was to become the leader of the German wing of this society.

But, on the flip side, the charitable interpretation notes that Jung only agreed to become president of the General Medical Society under certain conditions. The first being that the society become international so that it wasn’t simply a German affair but each nation would have their own group. And secondly that individuals could join without having to be part of national associations. This latter condition would allow Jewish practitioners in Germany to join — something which was otherwise cut off by their being barred from joining the German national society.

So on this first accusation we can either see Jung as an opportunist looking for his psychoanalytical model to triumph or as a pragmatist willing to risk reputational risk through entanglement with the Nazis if it allowed him to do some good for the Jewish practitioners who would have otherwise been barred from practice in Germany.

2. Promotion of Mein Kampf

All of which brings us to the second accusation: that Jung promoted Mein Kampf as required reading for psychotherapists.

This accusation arises from the first edition of the society’s publication Zentralblatt in December 1933. Göring was to be the editor of the German edition while Jung was to be the editor of the International edition. In the first international edition an editorial was published praising Nazi ideology, mandating that every practising psychotherapist take Hitler’s Mein Kampf as a basic reference and presenting Jung’s theories of archetypal cultural patterns as justification of the superiority of the Aryan race.

The optics on this, needless to say, are not very good.

But when we dig into the details what we find is that Jung wasn’t actively involved in the publishing wing of the organisation which was all being orchestrated in Germany. He was scandalised by this publication but instead of resigning he decided to let it slide. His argument was once again pragmatic: by letting this smear against his name stand he could do more good for the Jewish psychoanalysts in Germany than he could by attacking the editorial or resigning his post. As he put it:

“In this way my name unexpectedly appeared over a National Socialist manifesto, which to me personally was anything but agreeable. And yet after all—what is help or friendship that costs nothing?”

Jung inadvertently found himself entangled in politics and it’s understandable that his name has been so besmirched by this incident. But if we are to take him at his word then he willingly suffered the infamy of this undesirable connection in order to help the Jewish psychoanalysts in Germany.

The State of Psychotherapy Today (1934)

And that brings us to Jung’s article The State of Psychotherapy Today which was published a couple of months later in Zentralblatt. This one article is the primary source of the taint on Jung’s reputation and it is the source of the next five accusations.

It’s important to note that Jung himself expressed regret for this article. He later wrote to his friend (and his dentist) Dr Sigmund Hurwitz (who later became a Jungian analyst) that:

“I have written in my long life many books, and I have also written nonsense. Unfortunately, that [article] was nonsense.”

But this post-nut clarity did not immediately dawn on Jung. When this article was attacked in the Swiss media in 1934, Jung replied with a vigorous defence saying that these views were not simply signs of his hopping on the bandwagon. In this reply titled “Rejoinder to Dr Bally” Jung insisted that this was a deeply considered view that he had spoken about in 1918 and 1927.

And so in the case of this article we can’t simply dismiss it as a case of manipulation by dubious parties. These are Jung’s own words and his position on it is ambiguous. We are left wondering what exactly it is that Jung apologised for and what exactly he regretted in this article.

3. Jewish Science

Let’s look at the first accusation emerging from this article: the claim that Freud’s psychoanalytical school is Jewish Science.

The State of Psychotherapy Today consists mostly of an attack on the views of Freud and Adler (and, as Walter Kaufmann notes: in a forum they could not as Jewish people defend themselves in). About halfway through the article however we get past the theoretical differences with these other psychoanalytic founders and we come to the substantial difference between Freud and Adler on the one hand and Jung on the other: the former two are Jewish and the latter is Aryan. From there Jung dedicates a few pages to the differences between these two psychologies.

It is here that we come across the other soundbite accusations against Jung regarding the character of the Jewish psyche. The overarching point is that Freud and Adler’s psychological schools are fruits of this Jewish psychology. Consequently Jung claims that their work is a Jewish science rather than a universal one:

In my opinion it has been a grave error in medical psychology up till now to apply Jewish categories— which are not even binding on all Jews—indiscriminately to Germanic and Slavic Christendom.”

This quote in the article is a reiteration of a point he made in 1927 that:

“it is an inexcusable error to accept the conclusions of a Jewish psychology as generally valid.”

After Jung was slammed for his article in the Swiss press by a Dr Bally, Jung defended his arguments about Jewish and Aryan psychologies saying that

“Psychological differences obtain between all nations and races, and even between the inhabitants of Zurich, Basel, and Bern. (Where else would all the good jokes come from?) There are in fact differences between families and between individuals. That is why I attack every levelling psychology when it raises a claim to universal validity, as for instance the Freudian and the Adlerian. […] All branches of mankind unite in one stem—yes, but what is a stem without separate branches? Why this ridiculous touchiness when anybody dares to say anything about the psychological difference between Jews and Christians? Every child knows that differences exist.”

Jung’s attack on Freudian and Adlerian psychoanalysis as being Jewish then is akin to the more recent critiques of academic psychology. These critiques are suspicious of psychology’s claims to universality since the participants in psychological studies are predominantly university student volunteers who are paid to take part in the experiments. Or it might be compared to the pharmaceutical industry’s claims to universality coming under flack in the past five years in light of the underrepresentation of women or different ethnicities in clinical studies. Jung’s claim then can be read as being that the psychoanalysis of Freud and Adler — which was being promoted as a universal science — ignored the differences between cultures and peoples and thus was most valid for Central European Jewish people who at that time were its main practitioners as well as its main subjects of study.

This at least is the charitable reading but it is reinforced by his editorial in the December 1933 edition of the Zentralblatt — the same edition where Göring included the Nazi propaganda under Jung’s name — where Jung wrote that:

The differences which actually do exist between Germanic and Jewish psychology and which have long been known to every intelligent person are no longer to be glossed over, and this can only be beneficial to science. In psychology more than in any other science there is a “personal equation,” disregard of which falsifies the practical and theoretical findings. At the same time I should like to state expressly that this implies no depreciation of Semitic psychology, any more than it is a depreciation of the Chinese to speak of the peculiar psychology of the Oriental.

4. “Weak like women”

Now it is time to turn our attention to the specific insults Jung hurls at Jewish people in this article. And the first point might be to question this initial characterisation of these comments as insults.

When he characterises the Jewish people as being weak like women or having a lower potential psyche it seems that these comments can’t be anything but antisemitic. Given the context of Jung’s comments however and how they fit into the overall scheme of psychoanalytical literature of Freudians and Adlerians it seems that this is not necessarily antisemitic.

In contrast to the previous charges, of which I think the vast majority of people will find Jung to be innocent of antisemitism, the following charges are more of a judgement call. For some they will be antisemitic; for others they won’t.

Before we look at them in detail I would like to provide a couple of reasons why they mightn’t be read as antisemitic. The first is that the negative qualities listed above also have positive complements that Jung also discusses. They are part of a picture of a whole psychology that isn’t simply negative but nuanced.

The second reason why this might not be read as antisemitic is that Jung talks about the Aryan psychology in a similar way. And this Aryan psychology isn’t simply a glowering antithesis to the Jewish psychology but contains its own extremely negative shadings as we shall see.

If we look at Jung’s characterisations through the deconstructive lens of Jacques Derrida we see that Jung’s Binary Oppositions aren’t simply positive/Aryan vs. negative/Jewish but are more nuanced. It is not at all clear that the Jewish conception is less desirable than the Aryan one. If we see consciousness as a positive thing and animal savagery as a negative quality then we could argue the inverse.

And this is how we contextualise the comment that Jewish people are “weak like women” and also the comment that they have a lower potential psyche.

Freud and Adler have beheld very clearly the shadow that accompanies us all. The Jews have this peculiarity in common with women; being physically weaker, they have to aim at the chinks in the armour of their adversary, and thanks to this technique which has been forced on them through the centuries, the Jews themselves are best protected where others are most vulnerable. Because, again, of their civilization, more than twice as ancient as ours, they are vastly more conscious than we of human weaknesses, of the shadow-side of things, and hence in this respect much less vulnerable than we are. Thanks to their experience of an old culture, they are able, while fully conscious of their frailties, to live on friendly and even tolerant terms with them whereas we are still too young not to have “illusions” about ourselves.

So his comment that Jewish people are weak like women is a sort of backhanded insult. In the usual valuation of things consciousness is superior to unconsciousness and being in control of our psyche is better than being vulnerable to the unconscious. This is the standard hierarchy of these values and seen through this light Jung’s comments can be read by a charitable reader as complimentary to the Jewish psychology.

However the tone in which they are written seems to point in a different direction since usually the historical hierarchy of values holds manly above womanly. So there’s a bit of a mix of valuations here that is hard to tease apart. There are compliments and insults wrapped up in the same point.

This is what I meant by saying that these comments are nuanced and that some will read them as antisemitic while others will disagree.

5. Lower Potential Psyche

The next charge falls into the same category and the same conceptual frame. The consciousness of the Jewish people is already so differentiated that there is less potential for how it can unfold. As Jung puts it:

“As a member of a race with a three-thousand-year-old civilization, the Jew, like the cultured Chinese, has a wider area of psychological consciousness than we.”

This is the case with the Jewish psyche in contrast to the Aryan psyche. In contrast to the highly differentiated Jewish psychology, the Aryan psychology:

contains explosive forces and seeds of a future yet to be born, and these may not be devalued as nursery romanticism without psychic danger. The still youthful Germanic peoples are fully capable of creating new cultural forms that still lie dormant in the darkness of the unconscious of every individual – seeds bursting with energy and capable of mighty expansion

This follows on from Jung’s 1918 comparison between Jewish and Aryan psychologies where he wrote at length about this saying that:

“Christianity split the Germanic barbarian into an upper and a lower half, and enabled him, by repressing the dark side, to domesticate the brighter half and fit it for civilization. But the lower, darker half still awaits redemption and a second spell of domestication. Until then, it will remain associated with the vestiges of the prehistoric age, with the collective unconscious, which is subject to a peculiar and ever-increasing activation. As the Christian view of the world loses its authority, the more menacingly will the “blond beast” be heard prowling about in its underground prison, ready at any moment to burst out with devastating consequences. When this happens in the individual it brings about a psychological revolution, but it can also take a social form.

Jung’s belief then is that the weaker consciousness of the Aryan psychology is not strong enough (unlike the consciousness of Jewish psychology) to hold back the deluge of energy from the collective unconscious. The wilder unconscious of the barbarian Germanic psychology prowls its underground prison “ready at any moment to burst out with devastating consequences”.