Some topics remain taboo for science. When Georges Lemaître first proposed the Big Bang theory in the 1920s, there was a major backlash among many in the physics community—including Albert Einstein—who accused these physicists of importing a religious concept into science. The eminent British astronomer Fred Hoyle, who denied the Big Bang theory to his death in 2001 claimed:

“The reason why scientists like the “big bang” is because they are overshadowed by the Book of Genesis. It is deep within the psyche of most scientists to believe in the first page of Genesis.”

Such a comment seems ridiculous to us now given the widespread acceptance of the Big Bang theory. But it betrays the primal fear that the ocean of irrationality could still swallow the tiny island of reason called science. Science is still in its rebellious adolescence, and it must be wary of falling back into its childish state of obedience.

Any line of investigation gravitating too close to the religious or the occult is met with immediate suspicion. Carl Jung was a thinker who followed his own north star indifferent to the dangers of being labelled heretical. As with many such minds, Jung is a divisive thinker. For some he’s an analytic genius, for others he’s a bona fide mystic and for others again he is a captain of quackery.

Throughout his works, Jung repeatedly describes himself as an empiricist and emphasises the importance of grounding his work in empirical science. But because of his explorations in the psychology of seemingly bizarre subjects such as myths, dreams and alchemy, he ultimately fell between pillar and post. The taboo nature of such topics has led to his work being overlooked or dismissed out of hand.

In his incautious explorations of the ground between the scientific and religious worldviews, Jung defied convenient categorisation and the simplest solution was to disregard him. Freud’s explosive work was giving the culture more than enough to chew on at that time without Jung further complicating matters.

The collective unconscious is his most misunderstood contribution. It holds the rare prestige of being a theory that is misunderstood not only by its detractors but quite often by its advocates. While researching for this article, I did a quick search Reddit for the term and the first results (outside of the r/Jung subreddit) were very revealing.

Thread #1 IsItBullshit: Collective Unconscious

The first thread I came across was on r/IsItBullshit. The OP wanted a straw poll on whether people thought Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious was genuine article or cowpat. This was the top comment:

People behave differently in groups, things like group polarisation (groups often make more extreme decisions than single individuals would), or groupthink (all group members aligning their views) are well-documented. People in groups are also more susceptible to common biases and heuristics. Nonetheless, the concept of a hive brain as is suggested in psychoanalysis isn’t really considered to be true.

Thread #2 Is Carl Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious technically a metaphysical claim?

This second thread was a bit more accurate but still within the first few comments there was the following:

Yes. It rests on a theory of consciousness akin to a form of panpsychism. That’s metaphysical to me.

It is this breed of interpretation that has led to academics almost universally overlooking Jung’s work. Back when they were still friends and colleagues, Freud was afraid Jung’s occult interests would discredit the psychoanalytical movement which was still trying to find its feet as a science. Freud wrote to Jung in a letter from this time

I know that your deepest inclinations are impelling you toward a study of the occult and do not doubt that you will return with a rich cargo. There is no stopping that, and it is always right for a person to follow the biddings of his own impulses. The reputation you have won with your “Dementia” [Jung’s classic summary and integration of the literature on schizophrenia, published in 1907] will stand against the charge of “mystic” for quite a while. Only don’t stay too long away from us in those lush tropical colonies, it is necessary to govern at home. . . With cordial greetings and the hope that you will write me again after a shorter interval this time.

Jung’s curiosity for the fringes is the reason academics warn their colleagues and students against uttering his name in an academic context even today. His very name is liable to get one ostracised.

In the case of the collective unconscious, however, this reputation is wide of the mark. The wholesale dismissal of the collective unconscious as a half-baked theory about a paranormal hive mind is a complete misunderstanding.

The truth about the collective unconscious is both more straightforward and more fascinating than this claim of panpsychism would lead you to believe. It is a bridge between fairytales, instincts and ancient history.

The structure of the psyche:

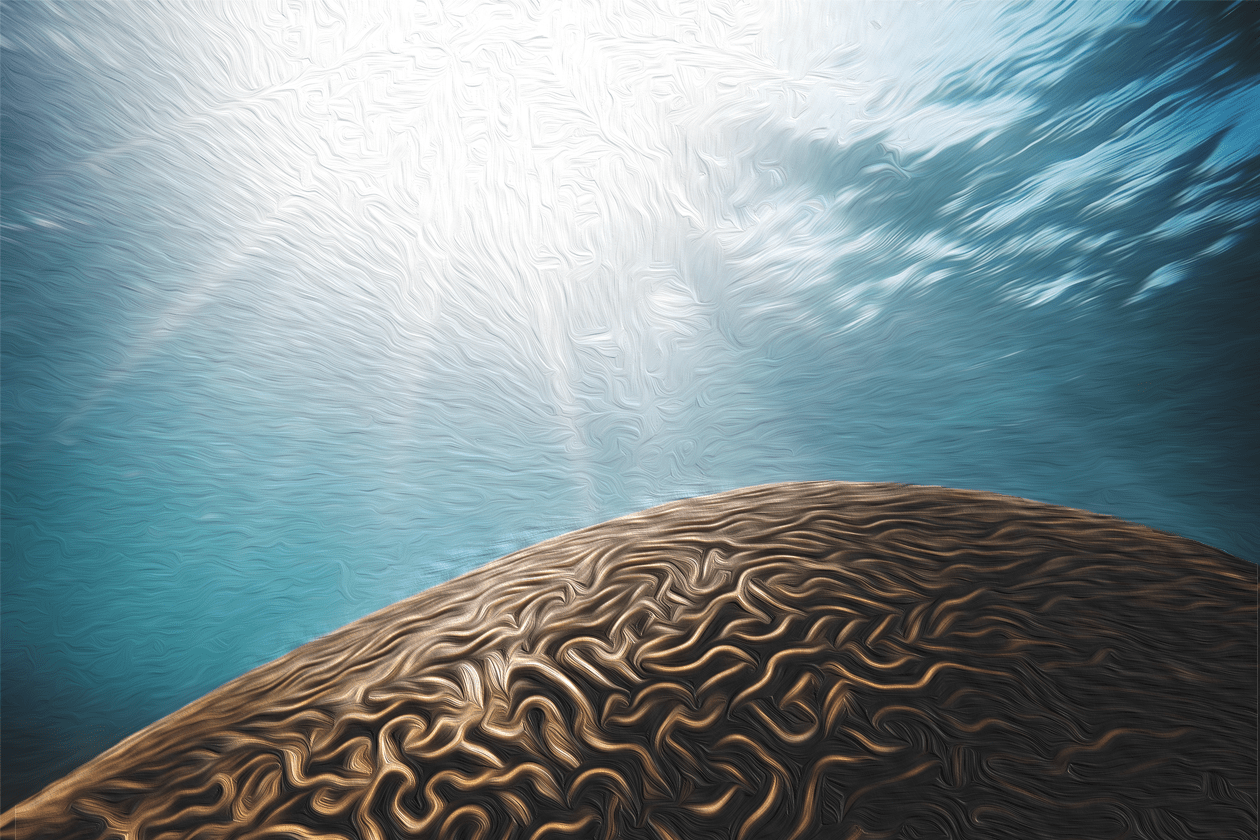

You can think of the psyche as an iceberg. The part above the surface is open to the air and easy to become acquainted with. But this is just the tip. Most of the iceberg is beneath the surface, hidden underwater.

The visible part of the iceberg is analogous to the conscious mind. For most of humanity’s history, this was the entirety of the mind, but the 19th century changed all this. At the turn of the 20th century, Freud’s star was on the rise and he popularised the conception of the unconscious (or as many call it—the subconscious).

The unconscious is the name we give to those parts of the mind that are outside of consciousness. In the analogy of the iceberg, the unconscious is the big chunk hiding beneath the water’s surface.

For Freud, this contained all the impulses, ideas and wishes that the individual represses. The reason for this repression is because they conflict with the taboos and mores of society. The unconscious is the swampland of shadowy, animalistic urges of the personality that every person buries to integrate into communal society.

The contents of this swampland remain active in the unconscious and it is these contents that cause neuroses and other phenomena like forgetting and slips of the tongue. Freud called these completely unconscious lower impulses the Id (which is Latin meaning ‘it’).

Jung followed Freud to this point but went further. Jung believed there was more in the unconscious than our questionable notions. It wasn’t just a dumping ground for antisocial urges but a whole world unto itself. This world was the birthplace of all myths, gods and magic. The depths of the iceberg were far deeper and far stranger than even Freud imagined.

What is the collective unconscious

Traditional psychoanalysis says that there are two layers to the mind: the conscious and the unconscious. Jung’s contribution was to distinguish separate layers in the unconscious: the personal unconscious and the collective unconscious.

The personal unconscious is home to all the people, things and places we have encountered in our own lives. All our personal experiences exist at this level. There is our personal mother and father, our friends and the things and places we have encountered in our lives.

The collective unconscious is far deeper than the personal. This layer contains the accumulated historical, collective experiences of humanity. It is not a mystical hive mind, however, but the psychology of the instincts of humanity. It is a common rather than a communal mind.

An analogy for this misinterpretation might go like this: biologists are claiming that humans have a collective body. The meaning of this, biologically-speaking, is that humans all over the world are working from the same blueprint. We are born with four limbs, opposable thumbs and an oversized brain. The analogous misreading would be something like: “biologists are claiming that all humans have the same body,” i.e. there are only four limbs, two opposable thumbs and one oversized brain in the entirety of the human species. That is a very different claim. The human body—like the collective unconscious—is common, not communal.

The biology and psychology of being human

So, the collective unconscious is the part of the mind we are all born with. But what are the contents of this collective aspect of the mind? The contents of the collective unconscious relate to the common experiences of humanity. They are the mental component of the instincts.

What do we mean by mental component? Well, everything in the human experience has a mental and a physical component. Let’s say you spilt some scalding water on your arm. If you were to look closely enough, you would see the nerve endings on your arm activate and send a message back up the nervous system towards the brain. That’s the physical side of the equation.

Pain is the mental side of the equation; you feel pain on your arm where the water hit you. The physical component (nerves firing) and the mental component (pain) are flip sides of the same experience.

Now let’s take a look at the more complicated example of a child entering adolescence. This transition to adulthood also has physical and mental components.

On the physical side, you could observe the significant physiological transformations that reshape the body. Or at a deeper level, you could look at their hormones going wild.

On the mental side, there is all the angst, anxiety and mood swings that accompany adolescence. There are the new ways of thinking and feeling about their peers, about the opposite sex, about music, about authority and everything else in the world. They are transforming in a way that cannot be satisfactorily explained by examining the physical component.

This adolescent transformation is the perfect example of an instinctual transformation. Adolescence doesn’t happen when a child chooses it. It’s not a switch that the parents flick-on. There is an instinctual level beyond consciousness or culture that initiates this transformation.

This deep biological level transcends culture. Biology doesn’t care if you are a 21st century American or a 5th century Bedouin; either way, you will have to pass through the crucible of adolescence.

This biological level is where we encounter the collective unconscious. The personal unconscious revolves around our personal struggles and our personal context. But some things are universally human: we were all children at one point, we all become adults and we will all eventually die. These are eternal facts of human life that bring with them predictable psychological and physiological changes.

The collective unconscious is the layer of the mind that is wired in alignment with these perennial aspects of being human. It is no more mystical than the freshly hatched turtle making a beeline for the sea.

Contents of the collective unconscious

Up to now, we have been describing what the collective unconscious is in broad terms. It is the mental component of the instincts. This instinctual layer runs deeper than the cultural and experientially conditioned conscious and personal unconscious. It is perennial in the same way as the form of the human body is perennial—it transcends cultural context. But what are the actual contents of the collective unconscious?

That is the question that Jung dedicated his life to. His life’s work was an exploration of the collective unconscious—its nature and how it manifests in the psychology of the individual.

When this layer is active, its contents begin to bubble up from this underworld of the psyche. These contents—whether they emerge in a 21st-century American teenager or a Roman matron two millennia ago—bear more resemblance to each other than they do to contents of consciousness or the personal unconscious.

It is out of this collective unconscious that the gods, the great heroes, and their attending myths and fairytales emerged. These supercharged contents of the collective unconscious bubble up and interact with the rest of the mind. This potent dose of primal energy acts as a catalyst in the reshaping of the individual’s psyche. It releases the resources needed to meet the overwhelming challenge facing them.

At such times, you might find yourself awakening in the depths of the night covered in sweat and your heart still racing in fear as you reassure yourself that you are not trapped in a maze fighting a giant snake.

The contents of the collective unconscious may not be ones that you have encountered in your personal life, but they contain themes that recur in ancient myths from across the world and across time. Jung’s investigation of this collective unconscious led him to the “lush tropical colonies” of religion, mythology and alchemy.

For Jung, these exotic contents corresponded to the activation of the instincts. At pivotal moments in our lives, something awakens deep inside us. These are the energies of transformation with all the power of four billion years of evolutionary refinement behind them. The mental manifestations of the instincts are what Jung called the collective unconscious. It is not a hive mind but a deep, ancient part of the mind which becomes activated when the tools of our ego and our culture are not enough.

2 Comments

Leave A Comment

Some topics remain taboo for science. When Georges Lemaître first proposed the Big Bang theory in the 1920s, there was a major backlash among many in the physics community—including Albert Einstein—who accused these physicists of importing a religious concept into science. The eminent British astronomer Fred Hoyle, who denied the Big Bang theory to his death in 2001 claimed:

“The reason why scientists like the “big bang” is because they are overshadowed by the Book of Genesis. It is deep within the psyche of most scientists to believe in the first page of Genesis.”

Such a comment seems ridiculous to us now given the widespread acceptance of the Big Bang theory. But it betrays the primal fear that the ocean of irrationality could still swallow the tiny island of reason called science. Science is still in its rebellious adolescence, and it must be wary of falling back into its childish state of obedience.

Any line of investigation gravitating too close to the religious or the occult is met with immediate suspicion. Carl Jung was a thinker who followed his own north star indifferent to the dangers of being labelled heretical. As with many such minds, Jung is a divisive thinker. For some he’s an analytic genius, for others he’s a bona fide mystic and for others again he is a captain of quackery.

Throughout his works, Jung repeatedly describes himself as an empiricist and emphasises the importance of grounding his work in empirical science. But because of his explorations in the psychology of seemingly bizarre subjects such as myths, dreams and alchemy, he ultimately fell between pillar and post. The taboo nature of such topics has led to his work being overlooked or dismissed out of hand.

In his incautious explorations of the ground between the scientific and religious worldviews, Jung defied convenient categorisation and the simplest solution was to disregard him. Freud’s explosive work was giving the culture more than enough to chew on at that time without Jung further complicating matters.

The collective unconscious is his most misunderstood contribution. It holds the rare prestige of being a theory that is misunderstood not only by its detractors but quite often by its advocates. While researching for this article, I did a quick search Reddit for the term and the first results (outside of the r/Jung subreddit) were very revealing.

Thread #1 IsItBullshit: Collective Unconscious

The first thread I came across was on r/IsItBullshit. The OP wanted a straw poll on whether people thought Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious was genuine article or cowpat. This was the top comment:

People behave differently in groups, things like group polarisation (groups often make more extreme decisions than single individuals would), or groupthink (all group members aligning their views) are well-documented. People in groups are also more susceptible to common biases and heuristics. Nonetheless, the concept of a hive brain as is suggested in psychoanalysis isn’t really considered to be true.

Thread #2 Is Carl Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious technically a metaphysical claim?

This second thread was a bit more accurate but still within the first few comments there was the following:

Yes. It rests on a theory of consciousness akin to a form of panpsychism. That’s metaphysical to me.

It is this breed of interpretation that has led to academics almost universally overlooking Jung’s work. Back when they were still friends and colleagues, Freud was afraid Jung’s occult interests would discredit the psychoanalytical movement which was still trying to find its feet as a science. Freud wrote to Jung in a letter from this time

I know that your deepest inclinations are impelling you toward a study of the occult and do not doubt that you will return with a rich cargo. There is no stopping that, and it is always right for a person to follow the biddings of his own impulses. The reputation you have won with your “Dementia” [Jung’s classic summary and integration of the literature on schizophrenia, published in 1907] will stand against the charge of “mystic” for quite a while. Only don’t stay too long away from us in those lush tropical colonies, it is necessary to govern at home. . . With cordial greetings and the hope that you will write me again after a shorter interval this time.

Jung’s curiosity for the fringes is the reason academics warn their colleagues and students against uttering his name in an academic context even today. His very name is liable to get one ostracised.

In the case of the collective unconscious, however, this reputation is wide of the mark. The wholesale dismissal of the collective unconscious as a half-baked theory about a paranormal hive mind is a complete misunderstanding.

The truth about the collective unconscious is both more straightforward and more fascinating than this claim of panpsychism would lead you to believe. It is a bridge between fairytales, instincts and ancient history.

The structure of the psyche:

You can think of the psyche as an iceberg. The part above the surface is open to the air and easy to become acquainted with. But this is just the tip. Most of the iceberg is beneath the surface, hidden underwater.

The visible part of the iceberg is analogous to the conscious mind. For most of humanity’s history, this was the entirety of the mind, but the 19th century changed all this. At the turn of the 20th century, Freud’s star was on the rise and he popularised the conception of the unconscious (or as many call it—the subconscious).

The unconscious is the name we give to those parts of the mind that are outside of consciousness. In the analogy of the iceberg, the unconscious is the big chunk hiding beneath the water’s surface.

For Freud, this contained all the impulses, ideas and wishes that the individual represses. The reason for this repression is because they conflict with the taboos and mores of society. The unconscious is the swampland of shadowy, animalistic urges of the personality that every person buries to integrate into communal society.

The contents of this swampland remain active in the unconscious and it is these contents that cause neuroses and other phenomena like forgetting and slips of the tongue. Freud called these completely unconscious lower impulses the Id (which is Latin meaning ‘it’).

Jung followed Freud to this point but went further. Jung believed there was more in the unconscious than our questionable notions. It wasn’t just a dumping ground for antisocial urges but a whole world unto itself. This world was the birthplace of all myths, gods and magic. The depths of the iceberg were far deeper and far stranger than even Freud imagined.

What is the collective unconscious

Traditional psychoanalysis says that there are two layers to the mind: the conscious and the unconscious. Jung’s contribution was to distinguish separate layers in the unconscious: the personal unconscious and the collective unconscious.

The personal unconscious is home to all the people, things and places we have encountered in our own lives. All our personal experiences exist at this level. There is our personal mother and father, our friends and the things and places we have encountered in our lives.

The collective unconscious is far deeper than the personal. This layer contains the accumulated historical, collective experiences of humanity. It is not a mystical hive mind, however, but the psychology of the instincts of humanity. It is a common rather than a communal mind.

An analogy for this misinterpretation might go like this: biologists are claiming that humans have a collective body. The meaning of this, biologically-speaking, is that humans all over the world are working from the same blueprint. We are born with four limbs, opposable thumbs and an oversized brain. The analogous misreading would be something like: “biologists are claiming that all humans have the same body,” i.e. there are only four limbs, two opposable thumbs and one oversized brain in the entirety of the human species. That is a very different claim. The human body—like the collective unconscious—is common, not communal.

The biology and psychology of being human

So, the collective unconscious is the part of the mind we are all born with. But what are the contents of this collective aspect of the mind? The contents of the collective unconscious relate to the common experiences of humanity. They are the mental component of the instincts.

What do we mean by mental component? Well, everything in the human experience has a mental and a physical component. Let’s say you spilt some scalding water on your arm. If you were to look closely enough, you would see the nerve endings on your arm activate and send a message back up the nervous system towards the brain. That’s the physical side of the equation.

Pain is the mental side of the equation; you feel pain on your arm where the water hit you. The physical component (nerves firing) and the mental component (pain) are flip sides of the same experience.

Now let’s take a look at the more complicated example of a child entering adolescence. This transition to adulthood also has physical and mental components.

On the physical side, you could observe the significant physiological transformations that reshape the body. Or at a deeper level, you could look at their hormones going wild.

On the mental side, there is all the angst, anxiety and mood swings that accompany adolescence. There are the new ways of thinking and feeling about their peers, about the opposite sex, about music, about authority and everything else in the world. They are transforming in a way that cannot be satisfactorily explained by examining the physical component.

This adolescent transformation is the perfect example of an instinctual transformation. Adolescence doesn’t happen when a child chooses it. It’s not a switch that the parents flick-on. There is an instinctual level beyond consciousness or culture that initiates this transformation.

This deep biological level transcends culture. Biology doesn’t care if you are a 21st century American or a 5th century Bedouin; either way, you will have to pass through the crucible of adolescence.

This biological level is where we encounter the collective unconscious. The personal unconscious revolves around our personal struggles and our personal context. But some things are universally human: we were all children at one point, we all become adults and we will all eventually die. These are eternal facts of human life that bring with them predictable psychological and physiological changes.

The collective unconscious is the layer of the mind that is wired in alignment with these perennial aspects of being human. It is no more mystical than the freshly hatched turtle making a beeline for the sea.

Contents of the collective unconscious

Up to now, we have been describing what the collective unconscious is in broad terms. It is the mental component of the instincts. This instinctual layer runs deeper than the cultural and experientially conditioned conscious and personal unconscious. It is perennial in the same way as the form of the human body is perennial—it transcends cultural context. But what are the actual contents of the collective unconscious?

That is the question that Jung dedicated his life to. His life’s work was an exploration of the collective unconscious—its nature and how it manifests in the psychology of the individual.

When this layer is active, its contents begin to bubble up from this underworld of the psyche. These contents—whether they emerge in a 21st-century American teenager or a Roman matron two millennia ago—bear more resemblance to each other than they do to contents of consciousness or the personal unconscious.

It is out of this collective unconscious that the gods, the great heroes, and their attending myths and fairytales emerged. These supercharged contents of the collective unconscious bubble up and interact with the rest of the mind. This potent dose of primal energy acts as a catalyst in the reshaping of the individual’s psyche. It releases the resources needed to meet the overwhelming challenge facing them.

At such times, you might find yourself awakening in the depths of the night covered in sweat and your heart still racing in fear as you reassure yourself that you are not trapped in a maze fighting a giant snake.

The contents of the collective unconscious may not be ones that you have encountered in your personal life, but they contain themes that recur in ancient myths from across the world and across time. Jung’s investigation of this collective unconscious led him to the “lush tropical colonies” of religion, mythology and alchemy.

For Jung, these exotic contents corresponded to the activation of the instincts. At pivotal moments in our lives, something awakens deep inside us. These are the energies of transformation with all the power of four billion years of evolutionary refinement behind them. The mental manifestations of the instincts are what Jung called the collective unconscious. It is not a hive mind but a deep, ancient part of the mind which becomes activated when the tools of our ego and our culture are not enough.

2 Comments

-

This was great, thank you for explaining.

Leave A Comment

Some topics remain taboo for science. When Georges Lemaître first proposed the Big Bang theory in the 1920s, there was a major backlash among many in the physics community—including Albert Einstein—who accused these physicists of importing a religious concept into science. The eminent British astronomer Fred Hoyle, who denied the Big Bang theory to his death in 2001 claimed:

“The reason why scientists like the “big bang” is because they are overshadowed by the Book of Genesis. It is deep within the psyche of most scientists to believe in the first page of Genesis.”

Such a comment seems ridiculous to us now given the widespread acceptance of the Big Bang theory. But it betrays the primal fear that the ocean of irrationality could still swallow the tiny island of reason called science. Science is still in its rebellious adolescence, and it must be wary of falling back into its childish state of obedience.

Any line of investigation gravitating too close to the religious or the occult is met with immediate suspicion. Carl Jung was a thinker who followed his own north star indifferent to the dangers of being labelled heretical. As with many such minds, Jung is a divisive thinker. For some he’s an analytic genius, for others he’s a bona fide mystic and for others again he is a captain of quackery.

Throughout his works, Jung repeatedly describes himself as an empiricist and emphasises the importance of grounding his work in empirical science. But because of his explorations in the psychology of seemingly bizarre subjects such as myths, dreams and alchemy, he ultimately fell between pillar and post. The taboo nature of such topics has led to his work being overlooked or dismissed out of hand.

In his incautious explorations of the ground between the scientific and religious worldviews, Jung defied convenient categorisation and the simplest solution was to disregard him. Freud’s explosive work was giving the culture more than enough to chew on at that time without Jung further complicating matters.

The collective unconscious is his most misunderstood contribution. It holds the rare prestige of being a theory that is misunderstood not only by its detractors but quite often by its advocates. While researching for this article, I did a quick search Reddit for the term and the first results (outside of the r/Jung subreddit) were very revealing.

Thread #1 IsItBullshit: Collective Unconscious

The first thread I came across was on r/IsItBullshit. The OP wanted a straw poll on whether people thought Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious was genuine article or cowpat. This was the top comment:

People behave differently in groups, things like group polarisation (groups often make more extreme decisions than single individuals would), or groupthink (all group members aligning their views) are well-documented. People in groups are also more susceptible to common biases and heuristics. Nonetheless, the concept of a hive brain as is suggested in psychoanalysis isn’t really considered to be true.

Thread #2 Is Carl Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious technically a metaphysical claim?

This second thread was a bit more accurate but still within the first few comments there was the following:

Yes. It rests on a theory of consciousness akin to a form of panpsychism. That’s metaphysical to me.

It is this breed of interpretation that has led to academics almost universally overlooking Jung’s work. Back when they were still friends and colleagues, Freud was afraid Jung’s occult interests would discredit the psychoanalytical movement which was still trying to find its feet as a science. Freud wrote to Jung in a letter from this time

I know that your deepest inclinations are impelling you toward a study of the occult and do not doubt that you will return with a rich cargo. There is no stopping that, and it is always right for a person to follow the biddings of his own impulses. The reputation you have won with your “Dementia” [Jung’s classic summary and integration of the literature on schizophrenia, published in 1907] will stand against the charge of “mystic” for quite a while. Only don’t stay too long away from us in those lush tropical colonies, it is necessary to govern at home. . . With cordial greetings and the hope that you will write me again after a shorter interval this time.

Jung’s curiosity for the fringes is the reason academics warn their colleagues and students against uttering his name in an academic context even today. His very name is liable to get one ostracised.

In the case of the collective unconscious, however, this reputation is wide of the mark. The wholesale dismissal of the collective unconscious as a half-baked theory about a paranormal hive mind is a complete misunderstanding.

The truth about the collective unconscious is both more straightforward and more fascinating than this claim of panpsychism would lead you to believe. It is a bridge between fairytales, instincts and ancient history.

The structure of the psyche:

You can think of the psyche as an iceberg. The part above the surface is open to the air and easy to become acquainted with. But this is just the tip. Most of the iceberg is beneath the surface, hidden underwater.

The visible part of the iceberg is analogous to the conscious mind. For most of humanity’s history, this was the entirety of the mind, but the 19th century changed all this. At the turn of the 20th century, Freud’s star was on the rise and he popularised the conception of the unconscious (or as many call it—the subconscious).

The unconscious is the name we give to those parts of the mind that are outside of consciousness. In the analogy of the iceberg, the unconscious is the big chunk hiding beneath the water’s surface.

For Freud, this contained all the impulses, ideas and wishes that the individual represses. The reason for this repression is because they conflict with the taboos and mores of society. The unconscious is the swampland of shadowy, animalistic urges of the personality that every person buries to integrate into communal society.

The contents of this swampland remain active in the unconscious and it is these contents that cause neuroses and other phenomena like forgetting and slips of the tongue. Freud called these completely unconscious lower impulses the Id (which is Latin meaning ‘it’).

Jung followed Freud to this point but went further. Jung believed there was more in the unconscious than our questionable notions. It wasn’t just a dumping ground for antisocial urges but a whole world unto itself. This world was the birthplace of all myths, gods and magic. The depths of the iceberg were far deeper and far stranger than even Freud imagined.

What is the collective unconscious

Traditional psychoanalysis says that there are two layers to the mind: the conscious and the unconscious. Jung’s contribution was to distinguish separate layers in the unconscious: the personal unconscious and the collective unconscious.

The personal unconscious is home to all the people, things and places we have encountered in our own lives. All our personal experiences exist at this level. There is our personal mother and father, our friends and the things and places we have encountered in our lives.

The collective unconscious is far deeper than the personal. This layer contains the accumulated historical, collective experiences of humanity. It is not a mystical hive mind, however, but the psychology of the instincts of humanity. It is a common rather than a communal mind.

An analogy for this misinterpretation might go like this: biologists are claiming that humans have a collective body. The meaning of this, biologically-speaking, is that humans all over the world are working from the same blueprint. We are born with four limbs, opposable thumbs and an oversized brain. The analogous misreading would be something like: “biologists are claiming that all humans have the same body,” i.e. there are only four limbs, two opposable thumbs and one oversized brain in the entirety of the human species. That is a very different claim. The human body—like the collective unconscious—is common, not communal.

The biology and psychology of being human

So, the collective unconscious is the part of the mind we are all born with. But what are the contents of this collective aspect of the mind? The contents of the collective unconscious relate to the common experiences of humanity. They are the mental component of the instincts.

What do we mean by mental component? Well, everything in the human experience has a mental and a physical component. Let’s say you spilt some scalding water on your arm. If you were to look closely enough, you would see the nerve endings on your arm activate and send a message back up the nervous system towards the brain. That’s the physical side of the equation.

Pain is the mental side of the equation; you feel pain on your arm where the water hit you. The physical component (nerves firing) and the mental component (pain) are flip sides of the same experience.

Now let’s take a look at the more complicated example of a child entering adolescence. This transition to adulthood also has physical and mental components.

On the physical side, you could observe the significant physiological transformations that reshape the body. Or at a deeper level, you could look at their hormones going wild.

On the mental side, there is all the angst, anxiety and mood swings that accompany adolescence. There are the new ways of thinking and feeling about their peers, about the opposite sex, about music, about authority and everything else in the world. They are transforming in a way that cannot be satisfactorily explained by examining the physical component.

This adolescent transformation is the perfect example of an instinctual transformation. Adolescence doesn’t happen when a child chooses it. It’s not a switch that the parents flick-on. There is an instinctual level beyond consciousness or culture that initiates this transformation.

This deep biological level transcends culture. Biology doesn’t care if you are a 21st century American or a 5th century Bedouin; either way, you will have to pass through the crucible of adolescence.

This biological level is where we encounter the collective unconscious. The personal unconscious revolves around our personal struggles and our personal context. But some things are universally human: we were all children at one point, we all become adults and we will all eventually die. These are eternal facts of human life that bring with them predictable psychological and physiological changes.

The collective unconscious is the layer of the mind that is wired in alignment with these perennial aspects of being human. It is no more mystical than the freshly hatched turtle making a beeline for the sea.

Contents of the collective unconscious

Up to now, we have been describing what the collective unconscious is in broad terms. It is the mental component of the instincts. This instinctual layer runs deeper than the cultural and experientially conditioned conscious and personal unconscious. It is perennial in the same way as the form of the human body is perennial—it transcends cultural context. But what are the actual contents of the collective unconscious?

That is the question that Jung dedicated his life to. His life’s work was an exploration of the collective unconscious—its nature and how it manifests in the psychology of the individual.

When this layer is active, its contents begin to bubble up from this underworld of the psyche. These contents—whether they emerge in a 21st-century American teenager or a Roman matron two millennia ago—bear more resemblance to each other than they do to contents of consciousness or the personal unconscious.

It is out of this collective unconscious that the gods, the great heroes, and their attending myths and fairytales emerged. These supercharged contents of the collective unconscious bubble up and interact with the rest of the mind. This potent dose of primal energy acts as a catalyst in the reshaping of the individual’s psyche. It releases the resources needed to meet the overwhelming challenge facing them.

At such times, you might find yourself awakening in the depths of the night covered in sweat and your heart still racing in fear as you reassure yourself that you are not trapped in a maze fighting a giant snake.

The contents of the collective unconscious may not be ones that you have encountered in your personal life, but they contain themes that recur in ancient myths from across the world and across time. Jung’s investigation of this collective unconscious led him to the “lush tropical colonies” of religion, mythology and alchemy.

For Jung, these exotic contents corresponded to the activation of the instincts. At pivotal moments in our lives, something awakens deep inside us. These are the energies of transformation with all the power of four billion years of evolutionary refinement behind them. The mental manifestations of the instincts are what Jung called the collective unconscious. It is not a hive mind but a deep, ancient part of the mind which becomes activated when the tools of our ego and our culture are not enough.

2 Comments

-

This was great, thank you for explaining.

This was great, thank you for explaining.

Glad you enjoyed it Suzy!