There are many fruitful comparisons between Socrates and the Roman Senator/Stoic philosopher Cato the Younger.

Some of these are amusing superficial comparisons: both men were partial to bouts of heavy drinking and philosophising — something we see Socrates do particularly well in Plato’s Symposium and something Cato was often slandered for.

But there is a much deeper vein of kinship between these two philosophical heavyweights. Both were philosophers who prioritised the living of philosophy over the writing about it. Both men cultivated lives of virtue and were not afraid to stamp on a few toes in the name of justice and integrity.

And then there is the ultimate comparison and one which Cato personally cultivated: both were faced with the ultimate test at the end of their lives; both were faced with a choice between compromising the integrity of their values and suicide. Both chose suicide.

Another similarity between the two thinkers is their galvanising effect on their philosophical traditions. It was Cato who made Stoicism a respectable Roman pursuit long before Seneca, Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius.

And yet for all the popularity of Stoicism in recent times, it is rare that the name Cato the Younger is mentioned. This fact is something of a historical absurdity considering he was, for many centuries, the embodiment of Stoicism. This article is one attempt to revive the esteem of this giant of the Stoic pantheon.

In the following we are going to explore

- the living philosophy of this Roman Socrates and why it was with Cato that the second-rate Greek philosophy Stoicism became a first-rate Roman religion

- why Cato was the gadfly of Julius Caesar and the only man he never forgave,

- the legacy of Cato through the ages and how his imprint is written all over the founding of America especially through its first president the man who was known as the American Cato.

The Roman zenith

Cato the Younger was a pivotal figure in the pivotal moment of Rome’s history. As a child he was a favourite of the dictator Sulla and he came of age as Pompey was having his glorious triumphs.

The real story of Cato’s life however was his relationship with Julius Caesar. Caesar was the antipode of everything Cato stood for; Cato spent his career attempting to thwart Caesar’s power-mongering — first with the Second Triumvirate and later with his dictatorial ambitions.

Cato felt that Rome had become decadent and lost touch with its ancient traditional values. He wanted to restore the virile and disciplined Rome that in reality had already been dead for over a century.

This rejuvenation of Roman values is where Stoicism enters the equation. Stoicism was as hard and as uncompromising as Cato aspired to be.

Stoicism in a nutshell

For a Stoic, whether you’re a foot underwater or a fathom you are drowning; an ounce of vice is a life of vice. The ideal that Stoics strive to embody is called the Sage but for the Stoics here are no sages only aspiring sages who fall more or less short of the ideal. The only possible exception to this rule was Socrates.

The Stoic philosopher is dedicated to virtue; the good life for them is synonymous with virtue. Everything else is indifferent—villas, consulships, glory. It’s not that these things are bad it’s simple that they are entirely unimportant. Also making the list of indifferents are big hitters such as pain, pleasure, life, death and starvation. To the Stoic none of these things matter one bit. Only one thing matters and that is virtue.

1. The Living Philosophy of Cato

The appeal of this uncompromising ascetic philosophy to a man like Cato is obvious. He looked around him and saw only corruption and decay; he looked to the glorious past of Rome and saw virtue and nobility, honour and dignity.

The ancient values of Rome were embodied in its legendary founder Romulus and its ideal citizen Cincinnatus — who was made dictator in a time of crisis and when the crisis was averted gave back the power and returned to his plough. But by the time of Cato the Younger, these simple values of Rome were dying.

In Stoicism Cato saw the values of ancient Rome mirrored and with that he fervently dedicated himself to it. He made the career-endangering choice to become the public face of Stoicism, a school widely regarded in his day as subversive and un-Roman.

Cato the Younger was a critical figure in Stoicism’s Romanisation; its transformation from a zany free-loving Greek philosophy to a respectable Roman philosophy. As Edith Hamilton noted in her book The Roman Way, on making its journey from Athens to Rome, this “second-rate Greek philosophy had developed into a first-rate Roman religion.”

The Roman brand of Stoicism that Cato made respectable put away the paradoxes, zany metaphysics and exotic edges and tailored its teaching to a people who loved things that worked.

Cato was a man of salt who lived his philosophy. He studied the works of the Stoics deeply but he himself was more like Socrates—he preferred that his philosophy be lived than written. His form of promotion was not through books but through example.

In an age when Rome was overflowing with wealth and culture, Cato lived a life of monkish simplicity. He turned his eyes backwards to the traditional past of Rome that he saw reflected in the philosophy of the Stoics.

What Cato learned from his tutor wasn’t first and foremost dialectics or paradoxes but exercises he could implement on the day they were learned. He learned how to get by on a poor man’s food or no food at all, how to go barefoot and bareheaded in rain and heat. He learned how to endure sickness in silence, how to speak bluntly and how to shut up, how to meditate on disaster and suffer the imagined loss of everything again and again.

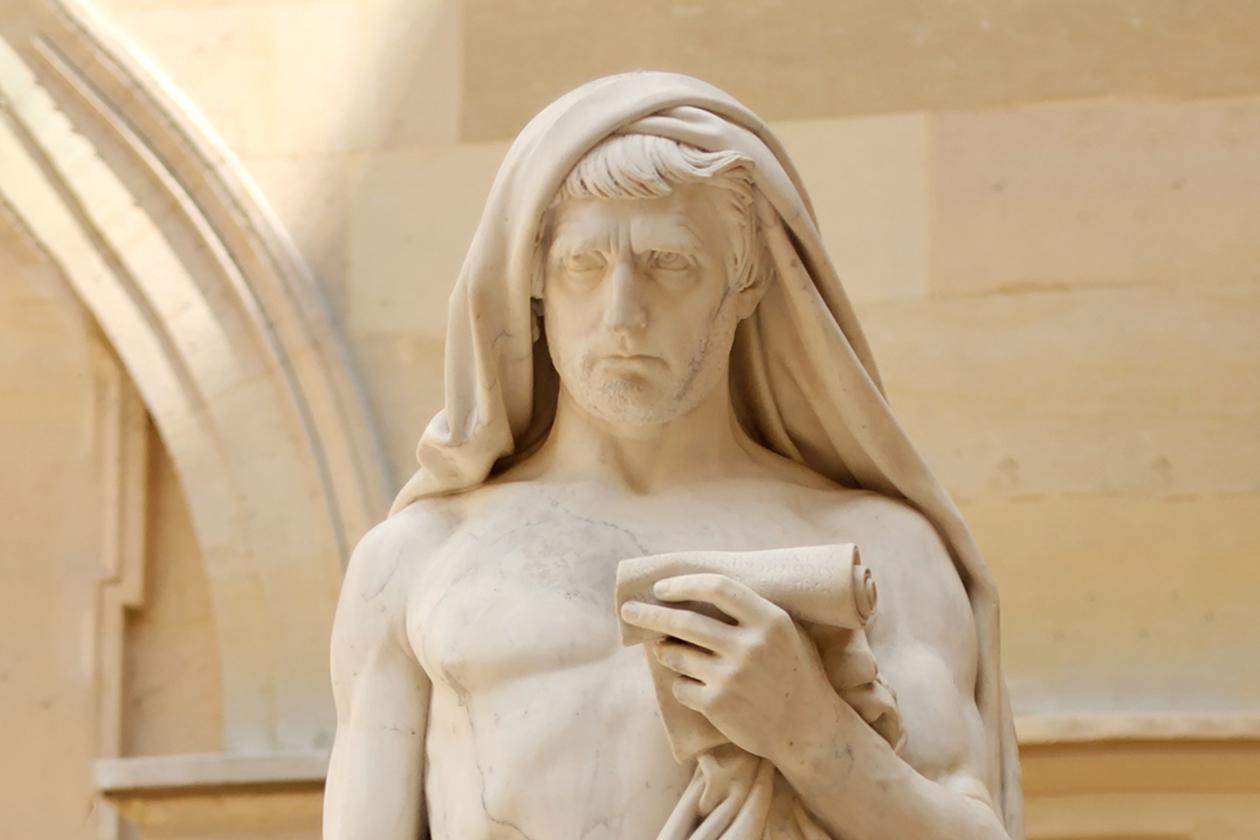

If you wanted to find someone who looked like Cato, the place to look was not at his fellow Senators but at the statues of Rome’s mythical founders. He was a walking anachronism.

Where powerful men gifted themselves villas and vineyards, Cato preferred a life of ascetic frugality. In a system that worked on bribery and favours, Cato’s vote famously had no price. He lived his life as a counterexample to the decadence of his age.

The Catonian shadow

All this talk of Cato’s great virtue and example might lead you to believe that he was some kind of saint. But like the rest of us he had his vices and dark side.

As we mentioned at the beginning he was partial to bouts of all-night drinking—albeit with the cheap wine of the people and with conversation revolving mostly around philosophy. He also suffered from a volcanic temper which is not so surprising from a highly strung rigidly moral type of individual.

He could be callous to his friends — choosing virtue and duty over any warmth of loyalty and in his married life there were some bizarre events resulting from his philosophical outlook.

On the whole Cato was a man who aspired to be a sage. He studied wisdom and every day tried to live wisdom. He is more human than Socrates in this sense. He doesn’t strike you as a man who is above it all, for whom wisdom is effortless. He comes across as someone who tried with all his will and lifeforce to live a life of wisdom. He often failed but that only makes his example more accessible.

One of the most interesting stories about Cato shows to us the only time we see the Stoic mask really crack. It’s the story of his older brother Caepio. Cato loved his brother deeply; there’s a story from when he was a child when someone asked him whom he loved most and he replied “My brother” Second most? “My brother.” Third most? “My brother.”

When Cato was in camp in Macedon with his legion, he heard news that his brother was dying. Despite a storm that carried a big risk of shipwreck, Cato chartered a small fishing vessel to navigate the storm but he arrived too late.

This was the moment that his Stoic philosophy ought to have prepared him for above all others but for this one moment in his life it proved utterly vapid. He embraced the corpse of his brother and sobbed over it and ordered the best incense and the best clothes burned with it on a pyre and he commissioned a massive marble likeness of his brother in this Thracian town. He was consumed by grief and it’s the one moment that his friends and enemies alike would remark that his philosophy abandoned him.

Cato the General

Other than this one blip, Cato’s life is a Stoic life. His Stoicism coloured his entire life and his interactions with everyone he met. You can often get the measure of a person not in how they deal with their equals but how they deal with those of a lower station in life. And in this vein, Cato’s time as a military tribune in command of his own legion gives a great insight into the unique dignity of his character.

The average Roman commander doled out brutal corporal punishment and instilled absolute discipline. But Cato was different.

Even as he approached the legion’s camp for the first time, he didn’t come on horseback as expected but on foot. And that was the way he always went. He was ready to live as hard as the common soldiers and imposed on himself the same discipline he imposed on them.

Cato, as Plutarch notes:

“thought it a trifling and useless task to make a display of his own virtue, which was that of a single man but was ambitious above all things to make the men under his command more like himself.”

He saw himself as an educator of his troops. Rather than reach for the lash at the first resort, Cato made a point of reasoning with his men. He imparted to them his Stoic philosophy of indifference to external events and focusing only on what is in one’s control.

“He made himself more like a soldier than a commander,” sleeping on the ground with his troops, eating the same meager food, wearing the same clothes, digging ditches beside them, and joining them on the march, always on foot.

Though Cato never made his soldiers rich with the spoils of a great conquest, they adored him. On the day of his departure, as he set off on foot, soldiers threw down their cloaks for him to walk on. They reportedly wept and kissed his hands.

There are few Roman commanders who could claim to be more loved by their men; he didn’t pander to his men seeking their validation. He saw himself as their educator but it was his willingness to share their toil with them that endeared him so deeply to them.

2. The Death of Cato

You can see his dedication to living philosophy rather than preaching or writing about it in his conduct with his troops. You can also see it in how he chose to die and this is the act of Cato that shined the brightest throughout the centuries.

When the civil war had gone awry and Caesar had basically won, Cato led a force of men on foot through 500 miles of North African desert to meet up with the rest of the Republican force that was holding out against the would-be dictator. And on this march, whenever the soldiers came to a rare source of water, Cato made a point of being the last to drink.

The republicans had hoped to hold out and launch a campaign from Utica but Caesar soon put an end to it. And when the game was up and Caesar had won, Cato chose to take his own life rather than live a single day under Caesar’s rule.

He sent for a copy of Plato’s Phaedo —his way of highlighting what was to follow. This is the Platonic dialogue where Socrates is forced to commit suicide by an unjust state and though he could escape he chooses to die with his virtue intact saying “the most important thing is not life, but the good life”.

Having read and according to Plutarch reread the Phaedo, Cato drove a sword into his chest. But death wasn’t destined to be so clean; he botched the job and surviving this he was stitched up and left to heal but when he awoke he ripped the stitches out and bled to death in an act of pure animal volition.

His stand for Republican virtues and against tyranny and this famous suicide made Cato the icon of civic duty.

3. Legacy: the Catonian centaur

Throughout Cato’s life there was a tension between Cato the myth and Cato the man. His example was like something out of an ancient legend in all its caricature. The reality of the living legend however was a rigid inflexible man. In many ways he was a myth before he was dead and his continued existence was just a nuisance for those who wanted to idolise him without being compelled to be chained to his inflexible moralism.

His reputation was long since established throughout Rome. The chronicler Valerius Maximus relates an anecdote that encapsulates the Roman public’s relationship to Cato. The story takes place during the weeklong May Day festival—which was like the Roman’s version of Carnival with drinking, farces, outrageously dyed clothing and prostitutes parading as queens.

During this festival Cato was sitting in the stands of the theatre enjoying the performance of the dancing miming girls with the rest of the crowd as he had done for the previous four decades of his life. But this time he received a message that the spectators would like to encourage the girls to take off their clothes but were embarrassed to do so with Cato present.

True to form Cato dutifully stood up and left to the loud applause of the crowd who then went back to their usual theatrical pleasures. That’s pretty much Cato’s life in a nutshell—he was applauded and admired for his virtue and integrity but nobody bothered to follow where he led.

The death of Cato the man allowed Cato the myth to finally take wings and take wings it did. Within a year of his death first Brutus then Cicero wrote their panegyric pamphlets in praise of Cato and these were followed by Caesar’s own Anticato which some have argued was one of the greatest missteps in his career. It seems Cato got under his skin in a way nobody else could.

The legacy of Cato

Even with the fading of Rome, the myth of Cato has continued to echo through the centuries. In the Divine Comedy, the pious Christian Dante makes Cato one of only four pagans to escape Hell. The Roman pagan Senator was proclaimed to be the Keeper of Purgatory. Dante makes him history’s greatest mortal symbol of god saying

“What man on earth was more worthy to signify God than Cato? Surely none.”

This seems all the more bizarre considering that Brutus — the man who was inflamed by Cato’s example of loyalty to the Republic — was down on the bottom level of Hell being chowed down on by the Devil himself.

A few centuries after Dante, Joseph Addison’s play Cato: A Tragedy became the canonical work of its day; it was the mark of an educated mind to recite and emulate the words and deeds of Addison’s play.

At the lowest ebb of the American Revolutionary War, the Revolutionary army was wintering in Valley Forge. With food scarce, warmth even scarcer and morale at its nadir, George Washington decided that Cato was the man to rejuvenate the souls of the troops and he staged Addington’s play in the camp.

For Washington, who was later known as the American Cato, and for all his fellow Revolutionaries Cato was liberty — the last man standing when Rome’s Republic fell.

His star has faded in recent centuries but his legacy has left an indelible mark on the modern world through his inflaming influence on the Founding Fathers of the US — especially its first president.

And so in these times when Stoicism is experiencing a renaissance, it is worth remembering the Roman Socrates who took a “second-rate Greek philosophy had developed into a first-rate Roman religion.” Without his Romanisation of Stoicism, we may not have the writings of Seneca, Epictetus or Marcus Aurelius and without his example perhaps we would have a very different America.

3 Comments

Leave A Comment

There are many fruitful comparisons between Socrates and the Roman Senator/Stoic philosopher Cato the Younger.

Some of these are amusing superficial comparisons: both men were partial to bouts of heavy drinking and philosophising — something we see Socrates do particularly well in Plato’s Symposium and something Cato was often slandered for.

But there is a much deeper vein of kinship between these two philosophical heavyweights. Both were philosophers who prioritised the living of philosophy over the writing about it. Both men cultivated lives of virtue and were not afraid to stamp on a few toes in the name of justice and integrity.

And then there is the ultimate comparison and one which Cato personally cultivated: both were faced with the ultimate test at the end of their lives; both were faced with a choice between compromising the integrity of their values and suicide. Both chose suicide.

Another similarity between the two thinkers is their galvanising effect on their philosophical traditions. It was Cato who made Stoicism a respectable Roman pursuit long before Seneca, Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius.

And yet for all the popularity of Stoicism in recent times, it is rare that the name Cato the Younger is mentioned. This fact is something of a historical absurdity considering he was, for many centuries, the embodiment of Stoicism. This article is one attempt to revive the esteem of this giant of the Stoic pantheon.

In the following we are going to explore

- the living philosophy of this Roman Socrates and why it was with Cato that the second-rate Greek philosophy Stoicism became a first-rate Roman religion

- why Cato was the gadfly of Julius Caesar and the only man he never forgave,

- the legacy of Cato through the ages and how his imprint is written all over the founding of America especially through its first president the man who was known as the American Cato.

The Roman zenith

Cato the Younger was a pivotal figure in the pivotal moment of Rome’s history. As a child he was a favourite of the dictator Sulla and he came of age as Pompey was having his glorious triumphs.

The real story of Cato’s life however was his relationship with Julius Caesar. Caesar was the antipode of everything Cato stood for; Cato spent his career attempting to thwart Caesar’s power-mongering — first with the Second Triumvirate and later with his dictatorial ambitions.

Cato felt that Rome had become decadent and lost touch with its ancient traditional values. He wanted to restore the virile and disciplined Rome that in reality had already been dead for over a century.

This rejuvenation of Roman values is where Stoicism enters the equation. Stoicism was as hard and as uncompromising as Cato aspired to be.

Stoicism in a nutshell

For a Stoic, whether you’re a foot underwater or a fathom you are drowning; an ounce of vice is a life of vice. The ideal that Stoics strive to embody is called the Sage but for the Stoics here are no sages only aspiring sages who fall more or less short of the ideal. The only possible exception to this rule was Socrates.

The Stoic philosopher is dedicated to virtue; the good life for them is synonymous with virtue. Everything else is indifferent—villas, consulships, glory. It’s not that these things are bad it’s simple that they are entirely unimportant. Also making the list of indifferents are big hitters such as pain, pleasure, life, death and starvation. To the Stoic none of these things matter one bit. Only one thing matters and that is virtue.

1. The Living Philosophy of Cato

The appeal of this uncompromising ascetic philosophy to a man like Cato is obvious. He looked around him and saw only corruption and decay; he looked to the glorious past of Rome and saw virtue and nobility, honour and dignity.

The ancient values of Rome were embodied in its legendary founder Romulus and its ideal citizen Cincinnatus — who was made dictator in a time of crisis and when the crisis was averted gave back the power and returned to his plough. But by the time of Cato the Younger, these simple values of Rome were dying.

In Stoicism Cato saw the values of ancient Rome mirrored and with that he fervently dedicated himself to it. He made the career-endangering choice to become the public face of Stoicism, a school widely regarded in his day as subversive and un-Roman.

Cato the Younger was a critical figure in Stoicism’s Romanisation; its transformation from a zany free-loving Greek philosophy to a respectable Roman philosophy. As Edith Hamilton noted in her book The Roman Way, on making its journey from Athens to Rome, this “second-rate Greek philosophy had developed into a first-rate Roman religion.”

The Roman brand of Stoicism that Cato made respectable put away the paradoxes, zany metaphysics and exotic edges and tailored its teaching to a people who loved things that worked.

Cato was a man of salt who lived his philosophy. He studied the works of the Stoics deeply but he himself was more like Socrates—he preferred that his philosophy be lived than written. His form of promotion was not through books but through example.

In an age when Rome was overflowing with wealth and culture, Cato lived a life of monkish simplicity. He turned his eyes backwards to the traditional past of Rome that he saw reflected in the philosophy of the Stoics.

What Cato learned from his tutor wasn’t first and foremost dialectics or paradoxes but exercises he could implement on the day they were learned. He learned how to get by on a poor man’s food or no food at all, how to go barefoot and bareheaded in rain and heat. He learned how to endure sickness in silence, how to speak bluntly and how to shut up, how to meditate on disaster and suffer the imagined loss of everything again and again.

If you wanted to find someone who looked like Cato, the place to look was not at his fellow Senators but at the statues of Rome’s mythical founders. He was a walking anachronism.

Where powerful men gifted themselves villas and vineyards, Cato preferred a life of ascetic frugality. In a system that worked on bribery and favours, Cato’s vote famously had no price. He lived his life as a counterexample to the decadence of his age.

The Catonian shadow

All this talk of Cato’s great virtue and example might lead you to believe that he was some kind of saint. But like the rest of us he had his vices and dark side.

As we mentioned at the beginning he was partial to bouts of all-night drinking—albeit with the cheap wine of the people and with conversation revolving mostly around philosophy. He also suffered from a volcanic temper which is not so surprising from a highly strung rigidly moral type of individual.

He could be callous to his friends — choosing virtue and duty over any warmth of loyalty and in his married life there were some bizarre events resulting from his philosophical outlook.

On the whole Cato was a man who aspired to be a sage. He studied wisdom and every day tried to live wisdom. He is more human than Socrates in this sense. He doesn’t strike you as a man who is above it all, for whom wisdom is effortless. He comes across as someone who tried with all his will and lifeforce to live a life of wisdom. He often failed but that only makes his example more accessible.

One of the most interesting stories about Cato shows to us the only time we see the Stoic mask really crack. It’s the story of his older brother Caepio. Cato loved his brother deeply; there’s a story from when he was a child when someone asked him whom he loved most and he replied “My brother” Second most? “My brother.” Third most? “My brother.”

When Cato was in camp in Macedon with his legion, he heard news that his brother was dying. Despite a storm that carried a big risk of shipwreck, Cato chartered a small fishing vessel to navigate the storm but he arrived too late.

This was the moment that his Stoic philosophy ought to have prepared him for above all others but for this one moment in his life it proved utterly vapid. He embraced the corpse of his brother and sobbed over it and ordered the best incense and the best clothes burned with it on a pyre and he commissioned a massive marble likeness of his brother in this Thracian town. He was consumed by grief and it’s the one moment that his friends and enemies alike would remark that his philosophy abandoned him.

Cato the General

Other than this one blip, Cato’s life is a Stoic life. His Stoicism coloured his entire life and his interactions with everyone he met. You can often get the measure of a person not in how they deal with their equals but how they deal with those of a lower station in life. And in this vein, Cato’s time as a military tribune in command of his own legion gives a great insight into the unique dignity of his character.

The average Roman commander doled out brutal corporal punishment and instilled absolute discipline. But Cato was different.

Even as he approached the legion’s camp for the first time, he didn’t come on horseback as expected but on foot. And that was the way he always went. He was ready to live as hard as the common soldiers and imposed on himself the same discipline he imposed on them.

Cato, as Plutarch notes:

“thought it a trifling and useless task to make a display of his own virtue, which was that of a single man but was ambitious above all things to make the men under his command more like himself.”

He saw himself as an educator of his troops. Rather than reach for the lash at the first resort, Cato made a point of reasoning with his men. He imparted to them his Stoic philosophy of indifference to external events and focusing only on what is in one’s control.

“He made himself more like a soldier than a commander,” sleeping on the ground with his troops, eating the same meager food, wearing the same clothes, digging ditches beside them, and joining them on the march, always on foot.

Though Cato never made his soldiers rich with the spoils of a great conquest, they adored him. On the day of his departure, as he set off on foot, soldiers threw down their cloaks for him to walk on. They reportedly wept and kissed his hands.

There are few Roman commanders who could claim to be more loved by their men; he didn’t pander to his men seeking their validation. He saw himself as their educator but it was his willingness to share their toil with them that endeared him so deeply to them.

2. The Death of Cato

You can see his dedication to living philosophy rather than preaching or writing about it in his conduct with his troops. You can also see it in how he chose to die and this is the act of Cato that shined the brightest throughout the centuries.

When the civil war had gone awry and Caesar had basically won, Cato led a force of men on foot through 500 miles of North African desert to meet up with the rest of the Republican force that was holding out against the would-be dictator. And on this march, whenever the soldiers came to a rare source of water, Cato made a point of being the last to drink.

The republicans had hoped to hold out and launch a campaign from Utica but Caesar soon put an end to it. And when the game was up and Caesar had won, Cato chose to take his own life rather than live a single day under Caesar’s rule.

He sent for a copy of Plato’s Phaedo —his way of highlighting what was to follow. This is the Platonic dialogue where Socrates is forced to commit suicide by an unjust state and though he could escape he chooses to die with his virtue intact saying “the most important thing is not life, but the good life”.

Having read and according to Plutarch reread the Phaedo, Cato drove a sword into his chest. But death wasn’t destined to be so clean; he botched the job and surviving this he was stitched up and left to heal but when he awoke he ripped the stitches out and bled to death in an act of pure animal volition.

His stand for Republican virtues and against tyranny and this famous suicide made Cato the icon of civic duty.

3. Legacy: the Catonian centaur

Throughout Cato’s life there was a tension between Cato the myth and Cato the man. His example was like something out of an ancient legend in all its caricature. The reality of the living legend however was a rigid inflexible man. In many ways he was a myth before he was dead and his continued existence was just a nuisance for those who wanted to idolise him without being compelled to be chained to his inflexible moralism.

His reputation was long since established throughout Rome. The chronicler Valerius Maximus relates an anecdote that encapsulates the Roman public’s relationship to Cato. The story takes place during the weeklong May Day festival—which was like the Roman’s version of Carnival with drinking, farces, outrageously dyed clothing and prostitutes parading as queens.

During this festival Cato was sitting in the stands of the theatre enjoying the performance of the dancing miming girls with the rest of the crowd as he had done for the previous four decades of his life. But this time he received a message that the spectators would like to encourage the girls to take off their clothes but were embarrassed to do so with Cato present.

True to form Cato dutifully stood up and left to the loud applause of the crowd who then went back to their usual theatrical pleasures. That’s pretty much Cato’s life in a nutshell—he was applauded and admired for his virtue and integrity but nobody bothered to follow where he led.

The death of Cato the man allowed Cato the myth to finally take wings and take wings it did. Within a year of his death first Brutus then Cicero wrote their panegyric pamphlets in praise of Cato and these were followed by Caesar’s own Anticato which some have argued was one of the greatest missteps in his career. It seems Cato got under his skin in a way nobody else could.

The legacy of Cato

Even with the fading of Rome, the myth of Cato has continued to echo through the centuries. In the Divine Comedy, the pious Christian Dante makes Cato one of only four pagans to escape Hell. The Roman pagan Senator was proclaimed to be the Keeper of Purgatory. Dante makes him history’s greatest mortal symbol of god saying

“What man on earth was more worthy to signify God than Cato? Surely none.”

This seems all the more bizarre considering that Brutus — the man who was inflamed by Cato’s example of loyalty to the Republic — was down on the bottom level of Hell being chowed down on by the Devil himself.

A few centuries after Dante, Joseph Addison’s play Cato: A Tragedy became the canonical work of its day; it was the mark of an educated mind to recite and emulate the words and deeds of Addison’s play.

At the lowest ebb of the American Revolutionary War, the Revolutionary army was wintering in Valley Forge. With food scarce, warmth even scarcer and morale at its nadir, George Washington decided that Cato was the man to rejuvenate the souls of the troops and he staged Addington’s play in the camp.

For Washington, who was later known as the American Cato, and for all his fellow Revolutionaries Cato was liberty — the last man standing when Rome’s Republic fell.

His star has faded in recent centuries but his legacy has left an indelible mark on the modern world through his inflaming influence on the Founding Fathers of the US — especially its first president.

And so in these times when Stoicism is experiencing a renaissance, it is worth remembering the Roman Socrates who took a “second-rate Greek philosophy had developed into a first-rate Roman religion.” Without his Romanisation of Stoicism, we may not have the writings of Seneca, Epictetus or Marcus Aurelius and without his example perhaps we would have a very different America.

3 Comments

-

[…] the Cynic is one that we looked at in a previous episode. The Ancient Roman senator Cato the Younger is another. He became so drenched in Stoic philosophy that he became a living embodiment of its […]

-

[…] series, we have looked at the living philosophies of three ancient thinkers: Epicurus, Diogenes and Cato the Younger and explored their varying formulations of the good […]

-

[…] example that always springs to mind when I think about this is Cato the Younger who was idealised by everyone from Dante to George Washington. Cato was a conservative Roman […]

Leave A Comment

There are many fruitful comparisons between Socrates and the Roman Senator/Stoic philosopher Cato the Younger.

Some of these are amusing superficial comparisons: both men were partial to bouts of heavy drinking and philosophising — something we see Socrates do particularly well in Plato’s Symposium and something Cato was often slandered for.

But there is a much deeper vein of kinship between these two philosophical heavyweights. Both were philosophers who prioritised the living of philosophy over the writing about it. Both men cultivated lives of virtue and were not afraid to stamp on a few toes in the name of justice and integrity.

And then there is the ultimate comparison and one which Cato personally cultivated: both were faced with the ultimate test at the end of their lives; both were faced with a choice between compromising the integrity of their values and suicide. Both chose suicide.

Another similarity between the two thinkers is their galvanising effect on their philosophical traditions. It was Cato who made Stoicism a respectable Roman pursuit long before Seneca, Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius.

And yet for all the popularity of Stoicism in recent times, it is rare that the name Cato the Younger is mentioned. This fact is something of a historical absurdity considering he was, for many centuries, the embodiment of Stoicism. This article is one attempt to revive the esteem of this giant of the Stoic pantheon.

In the following we are going to explore

- the living philosophy of this Roman Socrates and why it was with Cato that the second-rate Greek philosophy Stoicism became a first-rate Roman religion

- why Cato was the gadfly of Julius Caesar and the only man he never forgave,

- the legacy of Cato through the ages and how his imprint is written all over the founding of America especially through its first president the man who was known as the American Cato.

The Roman zenith

Cato the Younger was a pivotal figure in the pivotal moment of Rome’s history. As a child he was a favourite of the dictator Sulla and he came of age as Pompey was having his glorious triumphs.

The real story of Cato’s life however was his relationship with Julius Caesar. Caesar was the antipode of everything Cato stood for; Cato spent his career attempting to thwart Caesar’s power-mongering — first with the Second Triumvirate and later with his dictatorial ambitions.

Cato felt that Rome had become decadent and lost touch with its ancient traditional values. He wanted to restore the virile and disciplined Rome that in reality had already been dead for over a century.

This rejuvenation of Roman values is where Stoicism enters the equation. Stoicism was as hard and as uncompromising as Cato aspired to be.

Stoicism in a nutshell

For a Stoic, whether you’re a foot underwater or a fathom you are drowning; an ounce of vice is a life of vice. The ideal that Stoics strive to embody is called the Sage but for the Stoics here are no sages only aspiring sages who fall more or less short of the ideal. The only possible exception to this rule was Socrates.

The Stoic philosopher is dedicated to virtue; the good life for them is synonymous with virtue. Everything else is indifferent—villas, consulships, glory. It’s not that these things are bad it’s simple that they are entirely unimportant. Also making the list of indifferents are big hitters such as pain, pleasure, life, death and starvation. To the Stoic none of these things matter one bit. Only one thing matters and that is virtue.

1. The Living Philosophy of Cato

The appeal of this uncompromising ascetic philosophy to a man like Cato is obvious. He looked around him and saw only corruption and decay; he looked to the glorious past of Rome and saw virtue and nobility, honour and dignity.

The ancient values of Rome were embodied in its legendary founder Romulus and its ideal citizen Cincinnatus — who was made dictator in a time of crisis and when the crisis was averted gave back the power and returned to his plough. But by the time of Cato the Younger, these simple values of Rome were dying.

In Stoicism Cato saw the values of ancient Rome mirrored and with that he fervently dedicated himself to it. He made the career-endangering choice to become the public face of Stoicism, a school widely regarded in his day as subversive and un-Roman.

Cato the Younger was a critical figure in Stoicism’s Romanisation; its transformation from a zany free-loving Greek philosophy to a respectable Roman philosophy. As Edith Hamilton noted in her book The Roman Way, on making its journey from Athens to Rome, this “second-rate Greek philosophy had developed into a first-rate Roman religion.”

The Roman brand of Stoicism that Cato made respectable put away the paradoxes, zany metaphysics and exotic edges and tailored its teaching to a people who loved things that worked.

Cato was a man of salt who lived his philosophy. He studied the works of the Stoics deeply but he himself was more like Socrates—he preferred that his philosophy be lived than written. His form of promotion was not through books but through example.

In an age when Rome was overflowing with wealth and culture, Cato lived a life of monkish simplicity. He turned his eyes backwards to the traditional past of Rome that he saw reflected in the philosophy of the Stoics.

What Cato learned from his tutor wasn’t first and foremost dialectics or paradoxes but exercises he could implement on the day they were learned. He learned how to get by on a poor man’s food or no food at all, how to go barefoot and bareheaded in rain and heat. He learned how to endure sickness in silence, how to speak bluntly and how to shut up, how to meditate on disaster and suffer the imagined loss of everything again and again.

If you wanted to find someone who looked like Cato, the place to look was not at his fellow Senators but at the statues of Rome’s mythical founders. He was a walking anachronism.

Where powerful men gifted themselves villas and vineyards, Cato preferred a life of ascetic frugality. In a system that worked on bribery and favours, Cato’s vote famously had no price. He lived his life as a counterexample to the decadence of his age.

The Catonian shadow

All this talk of Cato’s great virtue and example might lead you to believe that he was some kind of saint. But like the rest of us he had his vices and dark side.

As we mentioned at the beginning he was partial to bouts of all-night drinking—albeit with the cheap wine of the people and with conversation revolving mostly around philosophy. He also suffered from a volcanic temper which is not so surprising from a highly strung rigidly moral type of individual.

He could be callous to his friends — choosing virtue and duty over any warmth of loyalty and in his married life there were some bizarre events resulting from his philosophical outlook.

On the whole Cato was a man who aspired to be a sage. He studied wisdom and every day tried to live wisdom. He is more human than Socrates in this sense. He doesn’t strike you as a man who is above it all, for whom wisdom is effortless. He comes across as someone who tried with all his will and lifeforce to live a life of wisdom. He often failed but that only makes his example more accessible.

One of the most interesting stories about Cato shows to us the only time we see the Stoic mask really crack. It’s the story of his older brother Caepio. Cato loved his brother deeply; there’s a story from when he was a child when someone asked him whom he loved most and he replied “My brother” Second most? “My brother.” Third most? “My brother.”

When Cato was in camp in Macedon with his legion, he heard news that his brother was dying. Despite a storm that carried a big risk of shipwreck, Cato chartered a small fishing vessel to navigate the storm but he arrived too late.

This was the moment that his Stoic philosophy ought to have prepared him for above all others but for this one moment in his life it proved utterly vapid. He embraced the corpse of his brother and sobbed over it and ordered the best incense and the best clothes burned with it on a pyre and he commissioned a massive marble likeness of his brother in this Thracian town. He was consumed by grief and it’s the one moment that his friends and enemies alike would remark that his philosophy abandoned him.

Cato the General

Other than this one blip, Cato’s life is a Stoic life. His Stoicism coloured his entire life and his interactions with everyone he met. You can often get the measure of a person not in how they deal with their equals but how they deal with those of a lower station in life. And in this vein, Cato’s time as a military tribune in command of his own legion gives a great insight into the unique dignity of his character.

The average Roman commander doled out brutal corporal punishment and instilled absolute discipline. But Cato was different.

Even as he approached the legion’s camp for the first time, he didn’t come on horseback as expected but on foot. And that was the way he always went. He was ready to live as hard as the common soldiers and imposed on himself the same discipline he imposed on them.

Cato, as Plutarch notes:

“thought it a trifling and useless task to make a display of his own virtue, which was that of a single man but was ambitious above all things to make the men under his command more like himself.”

He saw himself as an educator of his troops. Rather than reach for the lash at the first resort, Cato made a point of reasoning with his men. He imparted to them his Stoic philosophy of indifference to external events and focusing only on what is in one’s control.

“He made himself more like a soldier than a commander,” sleeping on the ground with his troops, eating the same meager food, wearing the same clothes, digging ditches beside them, and joining them on the march, always on foot.

Though Cato never made his soldiers rich with the spoils of a great conquest, they adored him. On the day of his departure, as he set off on foot, soldiers threw down their cloaks for him to walk on. They reportedly wept and kissed his hands.

There are few Roman commanders who could claim to be more loved by their men; he didn’t pander to his men seeking their validation. He saw himself as their educator but it was his willingness to share their toil with them that endeared him so deeply to them.

2. The Death of Cato

You can see his dedication to living philosophy rather than preaching or writing about it in his conduct with his troops. You can also see it in how he chose to die and this is the act of Cato that shined the brightest throughout the centuries.

When the civil war had gone awry and Caesar had basically won, Cato led a force of men on foot through 500 miles of North African desert to meet up with the rest of the Republican force that was holding out against the would-be dictator. And on this march, whenever the soldiers came to a rare source of water, Cato made a point of being the last to drink.

The republicans had hoped to hold out and launch a campaign from Utica but Caesar soon put an end to it. And when the game was up and Caesar had won, Cato chose to take his own life rather than live a single day under Caesar’s rule.

He sent for a copy of Plato’s Phaedo —his way of highlighting what was to follow. This is the Platonic dialogue where Socrates is forced to commit suicide by an unjust state and though he could escape he chooses to die with his virtue intact saying “the most important thing is not life, but the good life”.

Having read and according to Plutarch reread the Phaedo, Cato drove a sword into his chest. But death wasn’t destined to be so clean; he botched the job and surviving this he was stitched up and left to heal but when he awoke he ripped the stitches out and bled to death in an act of pure animal volition.

His stand for Republican virtues and against tyranny and this famous suicide made Cato the icon of civic duty.

3. Legacy: the Catonian centaur

Throughout Cato’s life there was a tension between Cato the myth and Cato the man. His example was like something out of an ancient legend in all its caricature. The reality of the living legend however was a rigid inflexible man. In many ways he was a myth before he was dead and his continued existence was just a nuisance for those who wanted to idolise him without being compelled to be chained to his inflexible moralism.

His reputation was long since established throughout Rome. The chronicler Valerius Maximus relates an anecdote that encapsulates the Roman public’s relationship to Cato. The story takes place during the weeklong May Day festival—which was like the Roman’s version of Carnival with drinking, farces, outrageously dyed clothing and prostitutes parading as queens.

During this festival Cato was sitting in the stands of the theatre enjoying the performance of the dancing miming girls with the rest of the crowd as he had done for the previous four decades of his life. But this time he received a message that the spectators would like to encourage the girls to take off their clothes but were embarrassed to do so with Cato present.

True to form Cato dutifully stood up and left to the loud applause of the crowd who then went back to their usual theatrical pleasures. That’s pretty much Cato’s life in a nutshell—he was applauded and admired for his virtue and integrity but nobody bothered to follow where he led.

The death of Cato the man allowed Cato the myth to finally take wings and take wings it did. Within a year of his death first Brutus then Cicero wrote their panegyric pamphlets in praise of Cato and these were followed by Caesar’s own Anticato which some have argued was one of the greatest missteps in his career. It seems Cato got under his skin in a way nobody else could.

The legacy of Cato

Even with the fading of Rome, the myth of Cato has continued to echo through the centuries. In the Divine Comedy, the pious Christian Dante makes Cato one of only four pagans to escape Hell. The Roman pagan Senator was proclaimed to be the Keeper of Purgatory. Dante makes him history’s greatest mortal symbol of god saying

“What man on earth was more worthy to signify God than Cato? Surely none.”

This seems all the more bizarre considering that Brutus — the man who was inflamed by Cato’s example of loyalty to the Republic — was down on the bottom level of Hell being chowed down on by the Devil himself.

A few centuries after Dante, Joseph Addison’s play Cato: A Tragedy became the canonical work of its day; it was the mark of an educated mind to recite and emulate the words and deeds of Addison’s play.

At the lowest ebb of the American Revolutionary War, the Revolutionary army was wintering in Valley Forge. With food scarce, warmth even scarcer and morale at its nadir, George Washington decided that Cato was the man to rejuvenate the souls of the troops and he staged Addington’s play in the camp.

For Washington, who was later known as the American Cato, and for all his fellow Revolutionaries Cato was liberty — the last man standing when Rome’s Republic fell.

His star has faded in recent centuries but his legacy has left an indelible mark on the modern world through his inflaming influence on the Founding Fathers of the US — especially its first president.

And so in these times when Stoicism is experiencing a renaissance, it is worth remembering the Roman Socrates who took a “second-rate Greek philosophy had developed into a first-rate Roman religion.” Without his Romanisation of Stoicism, we may not have the writings of Seneca, Epictetus or Marcus Aurelius and without his example perhaps we would have a very different America.

3 Comments

-

[…] the Cynic is one that we looked at in a previous episode. The Ancient Roman senator Cato the Younger is another. He became so drenched in Stoic philosophy that he became a living embodiment of its […]

-

[…] series, we have looked at the living philosophies of three ancient thinkers: Epicurus, Diogenes and Cato the Younger and explored their varying formulations of the good […]

-

[…] example that always springs to mind when I think about this is Cato the Younger who was idealised by everyone from Dante to George Washington. Cato was a conservative Roman […]

[…] the Cynic is one that we looked at in a previous episode. The Ancient Roman senator Cato the Younger is another. He became so drenched in Stoic philosophy that he became a living embodiment of its […]

[…] series, we have looked at the living philosophies of three ancient thinkers: Epicurus, Diogenes and Cato the Younger and explored their varying formulations of the good […]

[…] example that always springs to mind when I think about this is Cato the Younger who was idealised by everyone from Dante to George Washington. Cato was a conservative Roman […]