In the work of Epicurus, we found a philosophy that has a deep kinship with modern tastes. It was a philosophy where the gods didn’t exist, where death was a non-worry and where pleasure without pain was the aim of the game.

This Epicurean ideal of maximal pleasure/minimal pain has become the default ideal of the good life in our modern world. But the hedonist ideal is not the only game in town, and in antiquity, it wasn’t even the main game.

Diogenes and Cato the Younger are exemplars of this alternative ideal. While the Epicurean equation was a matter of pleasure/pain, this alternative ideal is a matter of values. These philosophers maintain that the good life is not the easy life or the pleasurable life but contains something more substantial.

For most of the ancient philosophers, that something more was virtue. This was often seen as living in accordance with nature (with human nature as essentially rational). This was the philosophy of Socrates and Aristotle, of the Stoics and the Cynics, of Plato and Pythagoras.

But taken more broadly, the difference can be framed as Positive Psychology’s two components of the good life: pleasure and meaning.

Radha and Higher Ideal

The good life in our minds is still tied up with the ideas of painlessness, pleasure, contentment, peace, and wisdom. But what if this is a red herring? What if this is a mischievous goal that distracts from the attainment of a truly good life?

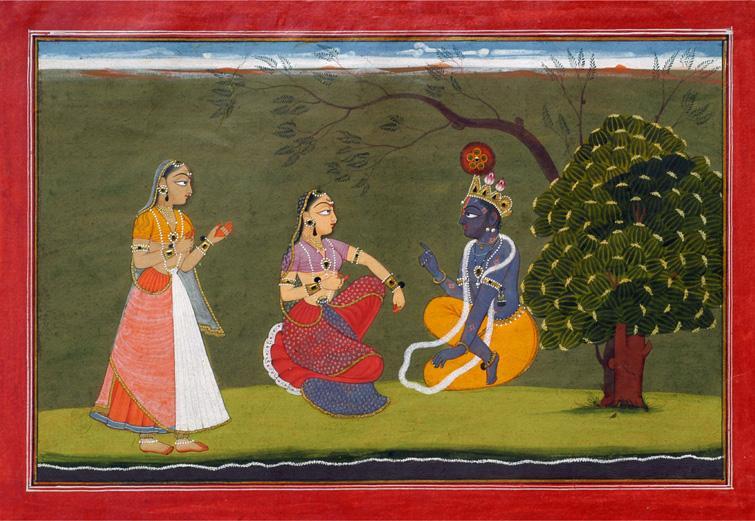

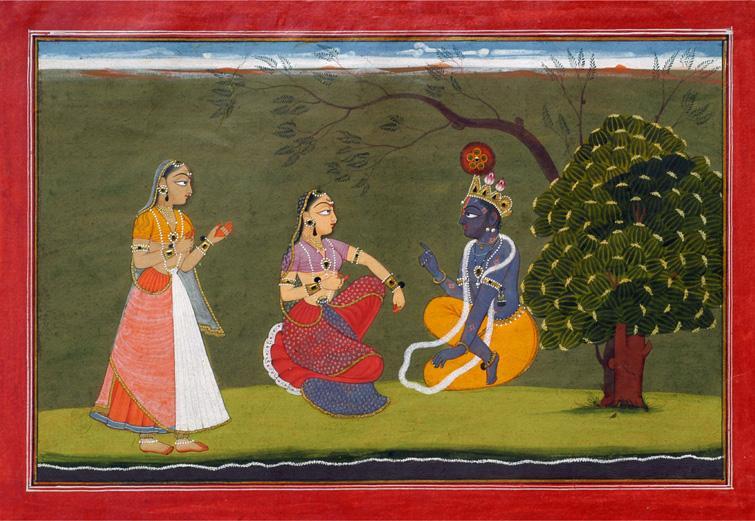

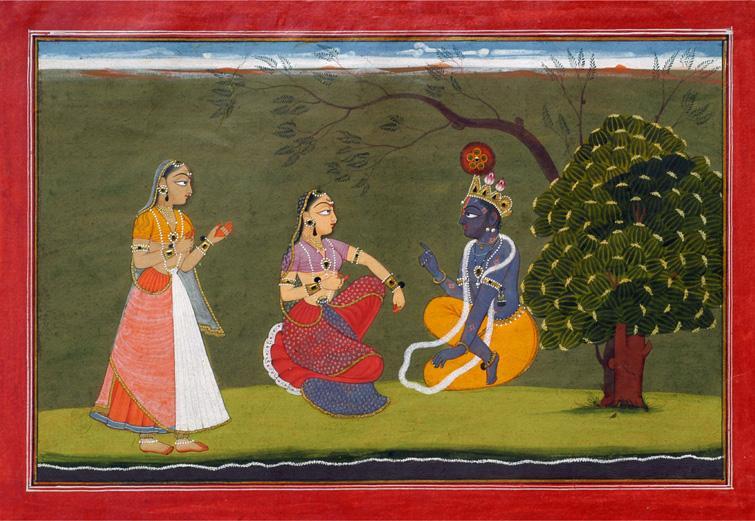

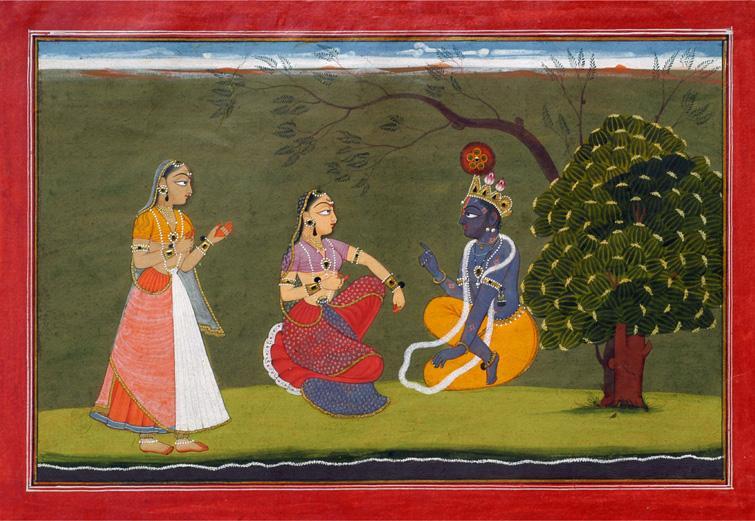

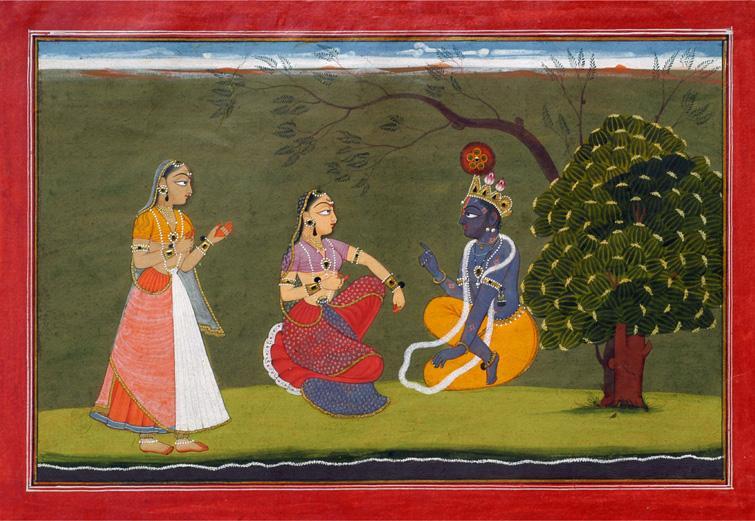

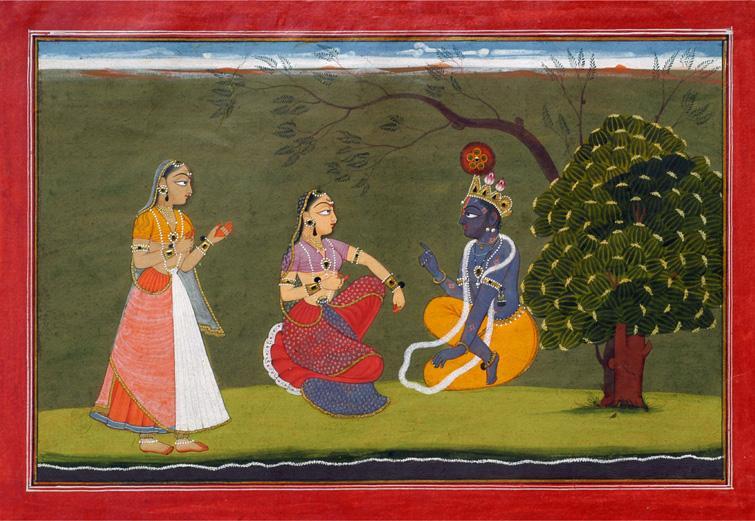

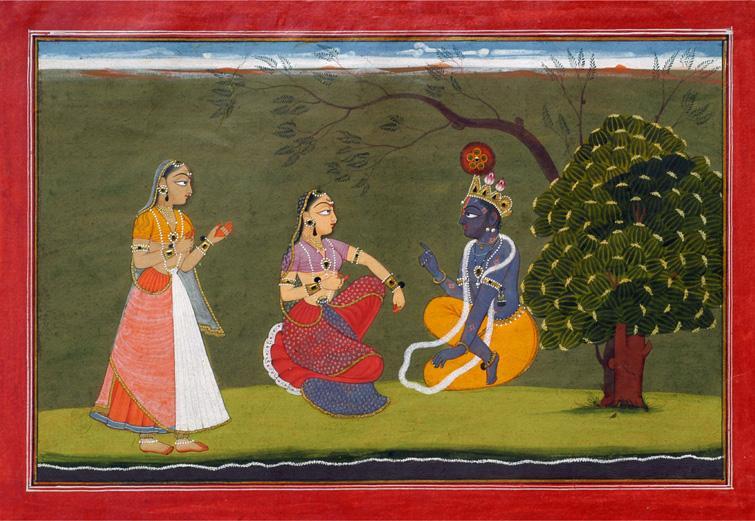

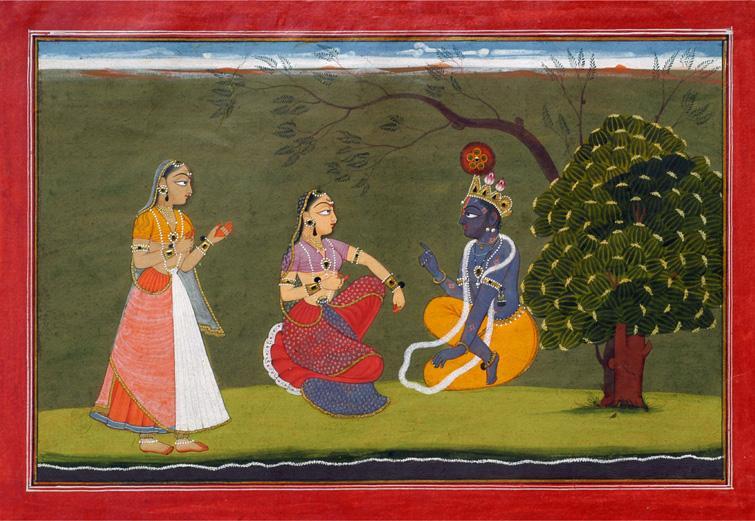

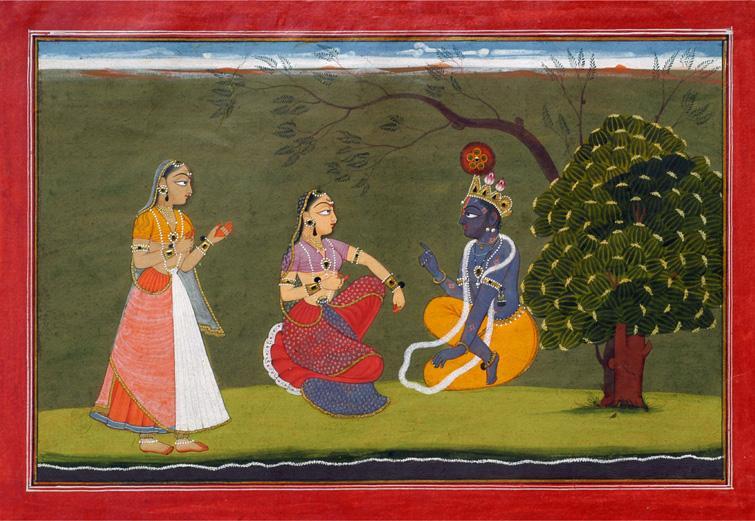

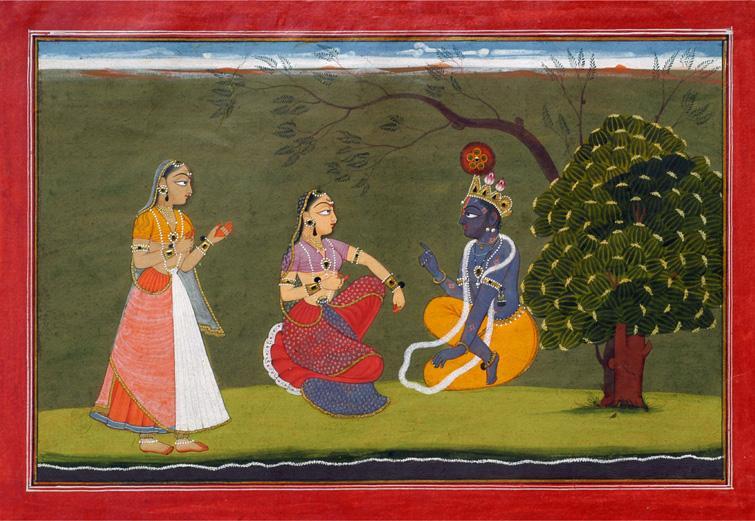

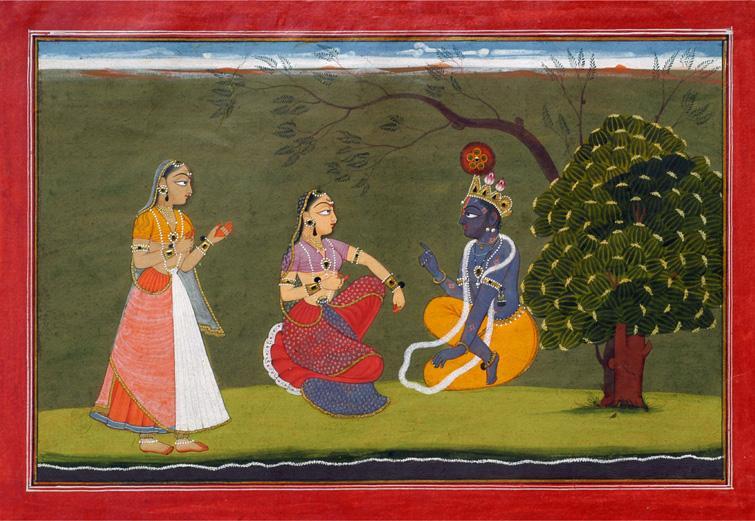

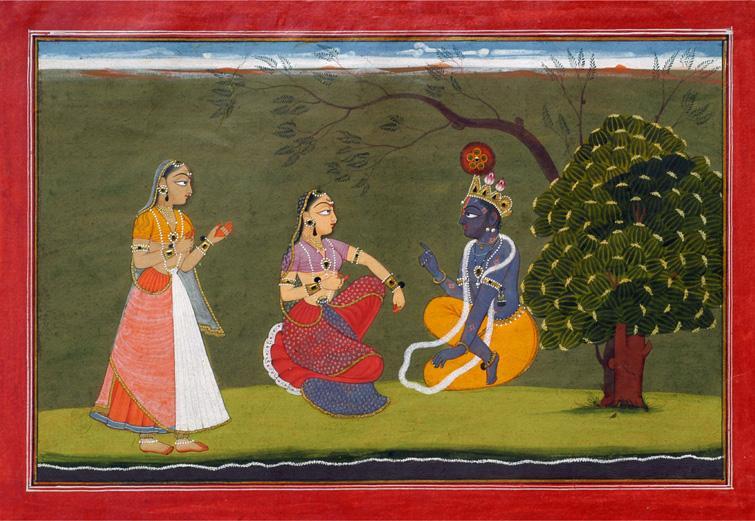

There is a story of the chief god Krishna in the Hindu religion, which might illustrate what we mean here.

One day the great god Krishna was playing his flute surrounded by his many wives when suddenly he experienced a great pain in his head.

He goes to each of the wives and asks her to stand on his head and each in turn refused. How could they do such a thing? To do so would be sacrilege, to do so would be an insult to Krishna and would see them sent to Hell.

But then Radha, the youngest of the wives, enters the scene and when she hears of Krishna’s predicament she immediately jumps on his head much to the scandal of the other wives. How dare you? How could you? Why would you do that? You will burn in hell for this.

To which Radha replies: I would be happy to spend in eternity in hell if it would bring my beloved a moment’s comfort.

You could draw many morals from this story, but what really stands out for our purposes is the idea that there is something more important than happiness.

The ideal of happiness is essentially nihilistic; it’s the best thing to pursue when there’s nothing more valuable on the table. In the absence of a higher goal, we default to the hedonistic calculus of basic pleasure and pain.

We see happiness emerging as an ideal when cultures reach a particular stage of development. As a civilisation grows more sophisticated, the old simplified narratives of religion come into question. Multiculturalism makes the parochialism of local religions seem absurd. And since religions tend to be the grand narratives that contain the higher ideals, when they fall, they take the orienting ideals with them.

This is the process of decadence that Nietzsche makes so much of: societies at this stage are victims of their own success and the opulence of decay sets in. In the rubble of the new flatland of ideals, the search for universals follows the tug of gravity and settles on the lowest common denominator.

Reductionist materialism, faced with the overwhelming complexity of reality, self-soothes by reducing reality to atomism; reductionist ethics copes with the complexity of value systems by reducing ethics to pleasure and pain.

This Hindu story points to a religious way of seeing something higher than happiness. It is not that Radha is the average believer. The traditional narrative of religion is to do good, and good things will come to you. Be good, and happiness will be your reward — of course, that reward is usually postponed to the afterlife.

But what this story illustrates is something about devotion. Radha is not serving Krishna for her own needs. She is not serving Krishna with an eye to eternal bliss or being rewarded for her deed. She believes she will be punished in Hell for her action but that is something she is willing to accept for her devotion.

This devotion goes beyond the carrot-stick-psychology of the traditional pious believer. Devotion is more vital than duty.

Man’s Search For Meaning

The pursuit of personal happiness is one step short of nihilism; it is a concession that there is nothing in this life worth striving for. Instead, the ideal of happiness steers us to a life of comfort and hedonism — whether that be the ascetic hedonism of Epicurus or the decadent hedonism of the epicure. Nothing has meaning and so we seek the life that is personally enjoyable.

Fear not death, fear not gods, what’s good is easy to grasp; what’s bad is easy to bear. It’s a simple recipe for life but not a particularly meaningful one. Would Epicurus have been satisfied with this four-part cure if he didn’t have the meaningful task of philosophising and spreading his living philosophy like a religion across the ancient Mediterranean?

But this myth reminds us of another mode of being — a way of life that overflows with meaning even if that meaning cuts us to the quick. They remind us that an encounter with Meaning leaves us willing to set aside visions of personal happiness to be part of something bigger.

There is no greater example of this than Viktor Frankl’s account of his experiences in the death camps of the Nazis. During his time in the camps (including the infamous Auschwitz), Frankl endured extreme starvation, inhuman treatment and slave labour in conditions of utter misery and squalor. He watched as men, women, and children died around him or as the Nazi guards took them to the gas chambers after their strength had failed them and they had lost the energy to carry on working.

Seventy-five percent of the people in Auschwitz died. Frankl’s mother, father, brother and wife all died in the concentration camps.

In Frankl’s account, we see that the furnaces of Hell do not universally break the spirit of humanity. Some prisoners regressed into a more animalistic state — losing touch with their humanity and becoming brutal survivalists. This is an understandable and perhaps the expected reaction to such an extreme situation. But what’s interesting and inspiring in Frankl’s account is the presence of another group that did not succumb to this mindset.

Frankl is the embodiment of this other group; despite all his struggles and personal losses with the concentration camps, he writes that “no human life is complete without suffering and death”. His living philosophy is neither hedonistic nor basic; perhaps having stared so deeply into the dark abysses of human nature, trite hedonism ceases to be an option.

In the book, Frankl tells us that his mantra in this time and since is the Nietzschean maxim: “he who has a why can handle almost any how”. He came to believe that those who had meaning could survive anything. He writes that “In some way, suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning, such as the meaning of a sacrifice.”

Musk’s Search For Meaning

Musk could have retired at the young age of 31 having made enough money from the sale of PayPal to live in luxury for his next hundred lives. From the vantage point of the value system that makes personal happiness the highest ideal, Musk’s trajectory looks completely irrational.

From a sufficient distance, Musk’s life seems an enviable paradise to many suffering from a lack of lucre. And yet his own words give us reasons to doubt this assumption as in his first appearance on the Joe Rogan Experience:

Rogan: What if there was a million [Nikola Teslas]?

Musk: Things would advance very quickly

Rogan: But there’s not. There’s not a million Elon Musks. There’s one motherfucker. Do you think about that? Or you just try to not?[long pause] Musk: Hmm…

Rogan: Hahaha

Musk: I don’t think you necessarily want to be me

Rogan: Well what’s the worst part about you?

Musk: I don’t think people would like it that much … It’s very hard to turn it off. It might sound great if it’s turned on but what if it doesn’t turn off…

Musk, of course, is a highly divisive character; to many, he’s just another billionaire sack of crap who wants to hoover up more and more money and power. But if we set aside the question of Musk’s value as a human being for a moment and take his statement at face value, it offers an interesting angle to our current discussion.

Musk’s lifestyle clearly is not driven by a hedonistic outlook. He has stated multiple times that it is purpose that drives his work on SpaceX, Tesla and Neuralink. As he sees it, several existential crises face human civilisation today, and these companies are his attempt to move the needle in the right direction.

“We’re running the most dangerous experiment in history right now, which is to see how much carbon dioxide the atmosphere… can handle before there is an environmental catastrophe.”

But it is not just fear of catastrophe that drives Musk. In SpaceX, we see the ambition to create a future that’s worth living in. “If you get up in the morning and think the future is going to be better, it is a bright day. Otherwise, it’s not.” But

“There have to be reasons that you get up in the morning and you want to live. Why do you want to live? What’s the point? What inspires you? What do you love about the future? If the future does not include being out there among the stars and being a multi-planet species, I find that incredibly depressing.”

The reason Musk did not retire to a life of limitless luxury at the age of 31 is that he believed that the good life did not lay in the direction of Epicurus but in the direction of Frankl. With Frankl, we see the value of meaning in Hell; with Musk, we see that meaning is also a valuable currency in Babylon.

The Middle Way

In plotting out our living philosophy in this age of secular modernity, the question we must ask ourselves is, what is our Krishna? What is the thing for which you are willing to suffer Hell?

It’s worth recalling the etymological origins of passion — it derives from the Latin word ‘patior’, meaning to suffer. To be passionate is to suffer; it’s to be driven like a lunatic towards what we love. As the old (falsely attributed) Bukowski goes: “Find what you love and let it kill you.”

Our passion is something that is willing to accept Hell in the service of love — in the service of something higher. We have found something that feels more meaningful to us than our own happiness.

With the death of God, the object of this passion can no longer be Krishna or Jesus. With the rise of secularism, such higher ideals crumbled. The object of passion has become more diffuse. Musk finds meaning in the dream of humans being multi-planetary; Frankl found meaning in sharing the truth of what happened in the concentration camps and the insights into human nature he witnessed there. For some, the higher ideal is environmentalism; for others, it’s poverty, equality or justice.

We see this passion of meaning all around us. There are more than enough causes and crises to motivate us. The point of this article has been to highlight the importance of meaning in any living philosophy. In the hedonist and reductionist philosophies such as Epicureanism and Utilitarianism, human wellbeing is reduced to its lowest common denominator: the binary of pleasure/pain. But this misses a core pillar of the good life.

In speaking of the highest ideal, happiness is a poor guide. Happiness points to a constant experience of positivity, but this is not the reality of the good life. Fulfilment is a more encompassing ideal — something we can aspire to and reach for that can give us more than mere happiness.

In the work of Epicurus, we found a philosophy that has a deep kinship with modern tastes. It was a philosophy where the gods didn’t exist, where death was a non-worry and where pleasure without pain was the aim of the game.

This Epicurean ideal of maximal pleasure/minimal pain has become the default ideal of the good life in our modern world. But the hedonist ideal is not the only game in town, and in antiquity, it wasn’t even the main game.

Diogenes and Cato the Younger are exemplars of this alternative ideal. While the Epicurean equation was a matter of pleasure/pain, this alternative ideal is a matter of values. These philosophers maintain that the good life is not the easy life or the pleasurable life but contains something more substantial.

For most of the ancient philosophers, that something more was virtue. This was often seen as living in accordance with nature (with human nature as essentially rational). This was the philosophy of Socrates and Aristotle, of the Stoics and the Cynics, of Plato and Pythagoras.

But taken more broadly, the difference can be framed as Positive Psychology’s two components of the good life: pleasure and meaning.

Radha and Higher Ideal

The good life in our minds is still tied up with the ideas of painlessness, pleasure, contentment, peace, and wisdom. But what if this is a red herring? What if this is a mischievous goal that distracts from the attainment of a truly good life?

There is a story of the chief god Krishna in the Hindu religion, which might illustrate what we mean here.

One day the great god Krishna was playing his flute surrounded by his many wives when suddenly he experienced a great pain in his head.

He goes to each of the wives and asks her to stand on his head and each in turn refused. How could they do such a thing? To do so would be sacrilege, to do so would be an insult to Krishna and would see them sent to Hell.

But then Radha, the youngest of the wives, enters the scene and when she hears of Krishna’s predicament she immediately jumps on his head much to the scandal of the other wives. How dare you? How could you? Why would you do that? You will burn in hell for this.

To which Radha replies: I would be happy to spend in eternity in hell if it would bring my beloved a moment’s comfort.

You could draw many morals from this story, but what really stands out for our purposes is the idea that there is something more important than happiness.

The ideal of happiness is essentially nihilistic; it’s the best thing to pursue when there’s nothing more valuable on the table. In the absence of a higher goal, we default to the hedonistic calculus of basic pleasure and pain.

We see happiness emerging as an ideal when cultures reach a particular stage of development. As a civilisation grows more sophisticated, the old simplified narratives of religion come into question. Multiculturalism makes the parochialism of local religions seem absurd. And since religions tend to be the grand narratives that contain the higher ideals, when they fall, they take the orienting ideals with them.

This is the process of decadence that Nietzsche makes so much of: societies at this stage are victims of their own success and the opulence of decay sets in. In the rubble of the new flatland of ideals, the search for universals follows the tug of gravity and settles on the lowest common denominator.

Reductionist materialism, faced with the overwhelming complexity of reality, self-soothes by reducing reality to atomism; reductionist ethics copes with the complexity of value systems by reducing ethics to pleasure and pain.

This Hindu story points to a religious way of seeing something higher than happiness. It is not that Radha is the average believer. The traditional narrative of religion is to do good, and good things will come to you. Be good, and happiness will be your reward — of course, that reward is usually postponed to the afterlife.

But what this story illustrates is something about devotion. Radha is not serving Krishna for her own needs. She is not serving Krishna with an eye to eternal bliss or being rewarded for her deed. She believes she will be punished in Hell for her action but that is something she is willing to accept for her devotion.

This devotion goes beyond the carrot-stick-psychology of the traditional pious believer. Devotion is more vital than duty.

Man’s Search For Meaning

The pursuit of personal happiness is one step short of nihilism; it is a concession that there is nothing in this life worth striving for. Instead, the ideal of happiness steers us to a life of comfort and hedonism — whether that be the ascetic hedonism of Epicurus or the decadent hedonism of the epicure. Nothing has meaning and so we seek the life that is personally enjoyable.

Fear not death, fear not gods, what’s good is easy to grasp; what’s bad is easy to bear. It’s a simple recipe for life but not a particularly meaningful one. Would Epicurus have been satisfied with this four-part cure if he didn’t have the meaningful task of philosophising and spreading his living philosophy like a religion across the ancient Mediterranean?

But this myth reminds us of another mode of being — a way of life that overflows with meaning even if that meaning cuts us to the quick. They remind us that an encounter with Meaning leaves us willing to set aside visions of personal happiness to be part of something bigger.

There is no greater example of this than Viktor Frankl’s account of his experiences in the death camps of the Nazis. During his time in the camps (including the infamous Auschwitz), Frankl endured extreme starvation, inhuman treatment and slave labour in conditions of utter misery and squalor. He watched as men, women, and children died around him or as the Nazi guards took them to the gas chambers after their strength had failed them and they had lost the energy to carry on working.

Seventy-five percent of the people in Auschwitz died. Frankl’s mother, father, brother and wife all died in the concentration camps.

In Frankl’s account, we see that the furnaces of Hell do not universally break the spirit of humanity. Some prisoners regressed into a more animalistic state — losing touch with their humanity and becoming brutal survivalists. This is an understandable and perhaps the expected reaction to such an extreme situation. But what’s interesting and inspiring in Frankl’s account is the presence of another group that did not succumb to this mindset.

Frankl is the embodiment of this other group; despite all his struggles and personal losses with the concentration camps, he writes that “no human life is complete without suffering and death”. His living philosophy is neither hedonistic nor basic; perhaps having stared so deeply into the dark abysses of human nature, trite hedonism ceases to be an option.

In the book, Frankl tells us that his mantra in this time and since is the Nietzschean maxim: “he who has a why can handle almost any how”. He came to believe that those who had meaning could survive anything. He writes that “In some way, suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning, such as the meaning of a sacrifice.”

Musk’s Search For Meaning

Musk could have retired at the young age of 31 having made enough money from the sale of PayPal to live in luxury for his next hundred lives. From the vantage point of the value system that makes personal happiness the highest ideal, Musk’s trajectory looks completely irrational.

From a sufficient distance, Musk’s life seems an enviable paradise to many suffering from a lack of lucre. And yet his own words give us reasons to doubt this assumption as in his first appearance on the Joe Rogan Experience:

Rogan: What if there was a million [Nikola Teslas]?

Musk: Things would advance very quickly

Rogan: But there’s not. There’s not a million Elon Musks. There’s one motherfucker. Do you think about that? Or you just try to not?[long pause] Musk: Hmm…

Rogan: Hahaha

Musk: I don’t think you necessarily want to be me

Rogan: Well what’s the worst part about you?

Musk: I don’t think people would like it that much … It’s very hard to turn it off. It might sound great if it’s turned on but what if it doesn’t turn off…

Musk, of course, is a highly divisive character; to many, he’s just another billionaire sack of crap who wants to hoover up more and more money and power. But if we set aside the question of Musk’s value as a human being for a moment and take his statement at face value, it offers an interesting angle to our current discussion.

Musk’s lifestyle clearly is not driven by a hedonistic outlook. He has stated multiple times that it is purpose that drives his work on SpaceX, Tesla and Neuralink. As he sees it, several existential crises face human civilisation today, and these companies are his attempt to move the needle in the right direction.

“We’re running the most dangerous experiment in history right now, which is to see how much carbon dioxide the atmosphere… can handle before there is an environmental catastrophe.”

But it is not just fear of catastrophe that drives Musk. In SpaceX, we see the ambition to create a future that’s worth living in. “If you get up in the morning and think the future is going to be better, it is a bright day. Otherwise, it’s not.” But

“There have to be reasons that you get up in the morning and you want to live. Why do you want to live? What’s the point? What inspires you? What do you love about the future? If the future does not include being out there among the stars and being a multi-planet species, I find that incredibly depressing.”

The reason Musk did not retire to a life of limitless luxury at the age of 31 is that he believed that the good life did not lay in the direction of Epicurus but in the direction of Frankl. With Frankl, we see the value of meaning in Hell; with Musk, we see that meaning is also a valuable currency in Babylon.

The Middle Way

In plotting out our living philosophy in this age of secular modernity, the question we must ask ourselves is, what is our Krishna? What is the thing for which you are willing to suffer Hell?

It’s worth recalling the etymological origins of passion — it derives from the Latin word ‘patior’, meaning to suffer. To be passionate is to suffer; it’s to be driven like a lunatic towards what we love. As the old (falsely attributed) Bukowski goes: “Find what you love and let it kill you.”

Our passion is something that is willing to accept Hell in the service of love — in the service of something higher. We have found something that feels more meaningful to us than our own happiness.

With the death of God, the object of this passion can no longer be Krishna or Jesus. With the rise of secularism, such higher ideals crumbled. The object of passion has become more diffuse. Musk finds meaning in the dream of humans being multi-planetary; Frankl found meaning in sharing the truth of what happened in the concentration camps and the insights into human nature he witnessed there. For some, the higher ideal is environmentalism; for others, it’s poverty, equality or justice.

We see this passion of meaning all around us. There are more than enough causes and crises to motivate us. The point of this article has been to highlight the importance of meaning in any living philosophy. In the hedonist and reductionist philosophies such as Epicureanism and Utilitarianism, human wellbeing is reduced to its lowest common denominator: the binary of pleasure/pain. But this misses a core pillar of the good life.

In speaking of the highest ideal, happiness is a poor guide. Happiness points to a constant experience of positivity, but this is not the reality of the good life. Fulfilment is a more encompassing ideal — something we can aspire to and reach for that can give us more than mere happiness.

Leave A Comment

In the work of Epicurus, we found a philosophy that has a deep kinship with modern tastes. It was a philosophy where the gods didn’t exist, where death was a non-worry and where pleasure without pain was the aim of the game.

This Epicurean ideal of maximal pleasure/minimal pain has become the default ideal of the good life in our modern world. But the hedonist ideal is not the only game in town, and in antiquity, it wasn’t even the main game.

Diogenes and Cato the Younger are exemplars of this alternative ideal. While the Epicurean equation was a matter of pleasure/pain, this alternative ideal is a matter of values. These philosophers maintain that the good life is not the easy life or the pleasurable life but contains something more substantial.

For most of the ancient philosophers, that something more was virtue. This was often seen as living in accordance with nature (with human nature as essentially rational). This was the philosophy of Socrates and Aristotle, of the Stoics and the Cynics, of Plato and Pythagoras.

But taken more broadly, the difference can be framed as Positive Psychology’s two components of the good life: pleasure and meaning.

Radha and Higher Ideal

The good life in our minds is still tied up with the ideas of painlessness, pleasure, contentment, peace, and wisdom. But what if this is a red herring? What if this is a mischievous goal that distracts from the attainment of a truly good life?

There is a story of the chief god Krishna in the Hindu religion, which might illustrate what we mean here.

One day the great god Krishna was playing his flute surrounded by his many wives when suddenly he experienced a great pain in his head.

He goes to each of the wives and asks her to stand on his head and each in turn refused. How could they do such a thing? To do so would be sacrilege, to do so would be an insult to Krishna and would see them sent to Hell.

But then Radha, the youngest of the wives, enters the scene and when she hears of Krishna’s predicament she immediately jumps on his head much to the scandal of the other wives. How dare you? How could you? Why would you do that? You will burn in hell for this.

To which Radha replies: I would be happy to spend in eternity in hell if it would bring my beloved a moment’s comfort.

You could draw many morals from this story, but what really stands out for our purposes is the idea that there is something more important than happiness.

The ideal of happiness is essentially nihilistic; it’s the best thing to pursue when there’s nothing more valuable on the table. In the absence of a higher goal, we default to the hedonistic calculus of basic pleasure and pain.

We see happiness emerging as an ideal when cultures reach a particular stage of development. As a civilisation grows more sophisticated, the old simplified narratives of religion come into question. Multiculturalism makes the parochialism of local religions seem absurd. And since religions tend to be the grand narratives that contain the higher ideals, when they fall, they take the orienting ideals with them.

This is the process of decadence that Nietzsche makes so much of: societies at this stage are victims of their own success and the opulence of decay sets in. In the rubble of the new flatland of ideals, the search for universals follows the tug of gravity and settles on the lowest common denominator.

Reductionist materialism, faced with the overwhelming complexity of reality, self-soothes by reducing reality to atomism; reductionist ethics copes with the complexity of value systems by reducing ethics to pleasure and pain.

This Hindu story points to a religious way of seeing something higher than happiness. It is not that Radha is the average believer. The traditional narrative of religion is to do good, and good things will come to you. Be good, and happiness will be your reward — of course, that reward is usually postponed to the afterlife.

But what this story illustrates is something about devotion. Radha is not serving Krishna for her own needs. She is not serving Krishna with an eye to eternal bliss or being rewarded for her deed. She believes she will be punished in Hell for her action but that is something she is willing to accept for her devotion.

This devotion goes beyond the carrot-stick-psychology of the traditional pious believer. Devotion is more vital than duty.

Man’s Search For Meaning

The pursuit of personal happiness is one step short of nihilism; it is a concession that there is nothing in this life worth striving for. Instead, the ideal of happiness steers us to a life of comfort and hedonism — whether that be the ascetic hedonism of Epicurus or the decadent hedonism of the epicure. Nothing has meaning and so we seek the life that is personally enjoyable.

Fear not death, fear not gods, what’s good is easy to grasp; what’s bad is easy to bear. It’s a simple recipe for life but not a particularly meaningful one. Would Epicurus have been satisfied with this four-part cure if he didn’t have the meaningful task of philosophising and spreading his living philosophy like a religion across the ancient Mediterranean?

But this myth reminds us of another mode of being — a way of life that overflows with meaning even if that meaning cuts us to the quick. They remind us that an encounter with Meaning leaves us willing to set aside visions of personal happiness to be part of something bigger.

There is no greater example of this than Viktor Frankl’s account of his experiences in the death camps of the Nazis. During his time in the camps (including the infamous Auschwitz), Frankl endured extreme starvation, inhuman treatment and slave labour in conditions of utter misery and squalor. He watched as men, women, and children died around him or as the Nazi guards took them to the gas chambers after their strength had failed them and they had lost the energy to carry on working.

Seventy-five percent of the people in Auschwitz died. Frankl’s mother, father, brother and wife all died in the concentration camps.

In Frankl’s account, we see that the furnaces of Hell do not universally break the spirit of humanity. Some prisoners regressed into a more animalistic state — losing touch with their humanity and becoming brutal survivalists. This is an understandable and perhaps the expected reaction to such an extreme situation. But what’s interesting and inspiring in Frankl’s account is the presence of another group that did not succumb to this mindset.

Frankl is the embodiment of this other group; despite all his struggles and personal losses with the concentration camps, he writes that “no human life is complete without suffering and death”. His living philosophy is neither hedonistic nor basic; perhaps having stared so deeply into the dark abysses of human nature, trite hedonism ceases to be an option.

In the book, Frankl tells us that his mantra in this time and since is the Nietzschean maxim: “he who has a why can handle almost any how”. He came to believe that those who had meaning could survive anything. He writes that “In some way, suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning, such as the meaning of a sacrifice.”

Musk’s Search For Meaning

Musk could have retired at the young age of 31 having made enough money from the sale of PayPal to live in luxury for his next hundred lives. From the vantage point of the value system that makes personal happiness the highest ideal, Musk’s trajectory looks completely irrational.

From a sufficient distance, Musk’s life seems an enviable paradise to many suffering from a lack of lucre. And yet his own words give us reasons to doubt this assumption as in his first appearance on the Joe Rogan Experience:

Rogan: What if there was a million [Nikola Teslas]?

Musk: Things would advance very quickly

Rogan: But there’s not. There’s not a million Elon Musks. There’s one motherfucker. Do you think about that? Or you just try to not?[long pause] Musk: Hmm…

Rogan: Hahaha

Musk: I don’t think you necessarily want to be me

Rogan: Well what’s the worst part about you?

Musk: I don’t think people would like it that much … It’s very hard to turn it off. It might sound great if it’s turned on but what if it doesn’t turn off…

Musk, of course, is a highly divisive character; to many, he’s just another billionaire sack of crap who wants to hoover up more and more money and power. But if we set aside the question of Musk’s value as a human being for a moment and take his statement at face value, it offers an interesting angle to our current discussion.

Musk’s lifestyle clearly is not driven by a hedonistic outlook. He has stated multiple times that it is purpose that drives his work on SpaceX, Tesla and Neuralink. As he sees it, several existential crises face human civilisation today, and these companies are his attempt to move the needle in the right direction.

“We’re running the most dangerous experiment in history right now, which is to see how much carbon dioxide the atmosphere… can handle before there is an environmental catastrophe.”

But it is not just fear of catastrophe that drives Musk. In SpaceX, we see the ambition to create a future that’s worth living in. “If you get up in the morning and think the future is going to be better, it is a bright day. Otherwise, it’s not.” But

“There have to be reasons that you get up in the morning and you want to live. Why do you want to live? What’s the point? What inspires you? What do you love about the future? If the future does not include being out there among the stars and being a multi-planet species, I find that incredibly depressing.”

The reason Musk did not retire to a life of limitless luxury at the age of 31 is that he believed that the good life did not lay in the direction of Epicurus but in the direction of Frankl. With Frankl, we see the value of meaning in Hell; with Musk, we see that meaning is also a valuable currency in Babylon.

The Middle Way

In plotting out our living philosophy in this age of secular modernity, the question we must ask ourselves is, what is our Krishna? What is the thing for which you are willing to suffer Hell?

It’s worth recalling the etymological origins of passion — it derives from the Latin word ‘patior’, meaning to suffer. To be passionate is to suffer; it’s to be driven like a lunatic towards what we love. As the old (falsely attributed) Bukowski goes: “Find what you love and let it kill you.”

Our passion is something that is willing to accept Hell in the service of love — in the service of something higher. We have found something that feels more meaningful to us than our own happiness.

With the death of God, the object of this passion can no longer be Krishna or Jesus. With the rise of secularism, such higher ideals crumbled. The object of passion has become more diffuse. Musk finds meaning in the dream of humans being multi-planetary; Frankl found meaning in sharing the truth of what happened in the concentration camps and the insights into human nature he witnessed there. For some, the higher ideal is environmentalism; for others, it’s poverty, equality or justice.

We see this passion of meaning all around us. There are more than enough causes and crises to motivate us. The point of this article has been to highlight the importance of meaning in any living philosophy. In the hedonist and reductionist philosophies such as Epicureanism and Utilitarianism, human wellbeing is reduced to its lowest common denominator: the binary of pleasure/pain. But this misses a core pillar of the good life.

In speaking of the highest ideal, happiness is a poor guide. Happiness points to a constant experience of positivity, but this is not the reality of the good life. Fulfilment is a more encompassing ideal — something we can aspire to and reach for that can give us more than mere happiness.