Since Habermas wrote these words in 1981, this situation has only become more acute. Now, well into the 21st century, the trenches of the so-called culture war are drawn by the tension of Modernism vs Postmodernism. These two worldviews — as radically different as the Medieval and the Modern — still have much of an overlap.

In this article, we are going to explore the meaning of these two terms — their historical origins, their traits and of course their differences.

“Postmodernity definitely presents itself as Antimodernity.” This statement describes an emotional current of our times which has penetrated all spheres of intellectual life. It has placed on the agenda theories of post-enlightenment, postmodernity, even of posthistory

—Jurgen Habermas, Modernity vs. Postmodernity (1981)

Modernism

The word Modern is a nebulous term that has been used to refer to the contemporary day and age since the 6th century AD. But in the past few decades, a particular time period has come to be identified as Modernity.

The dates of this cultural phase vary with some calling everything after the Middle Ages Modernity; others divide the modern era into three phases:

- Early Modernity: corresponding to the French Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution;

- Classical Modernity: corresponding to the Long 19th Century; and

- Late Modernity: which ended somewhere between 1968 and 1989.

For our purposes here the exact dates do not matter because we’re not really talking about a historical period. Following Foucault’s analysis in his essay What is Enlightenment? we will be treating modernity more “as an attitude than as a period of history.”

And this attitude is most salient in the period known as the Long 19th Century which spanned from the French Revolution in 1789 to the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. This was the time when Modernity had come into its fullness and was the dominant force in the culture.

Foucault identifies a number of traits of Modernity including:

- a questioning or rejection of tradition;

- the prioritising of individualism, freedom and formal equality;

- faith in inevitable social, scientific and technological progress,

- a movement from feudalism toward capitalism and the market economy,

- industrialization and urbanization,

- secularization and,

- the development of the nation-state, representative democracy and public education

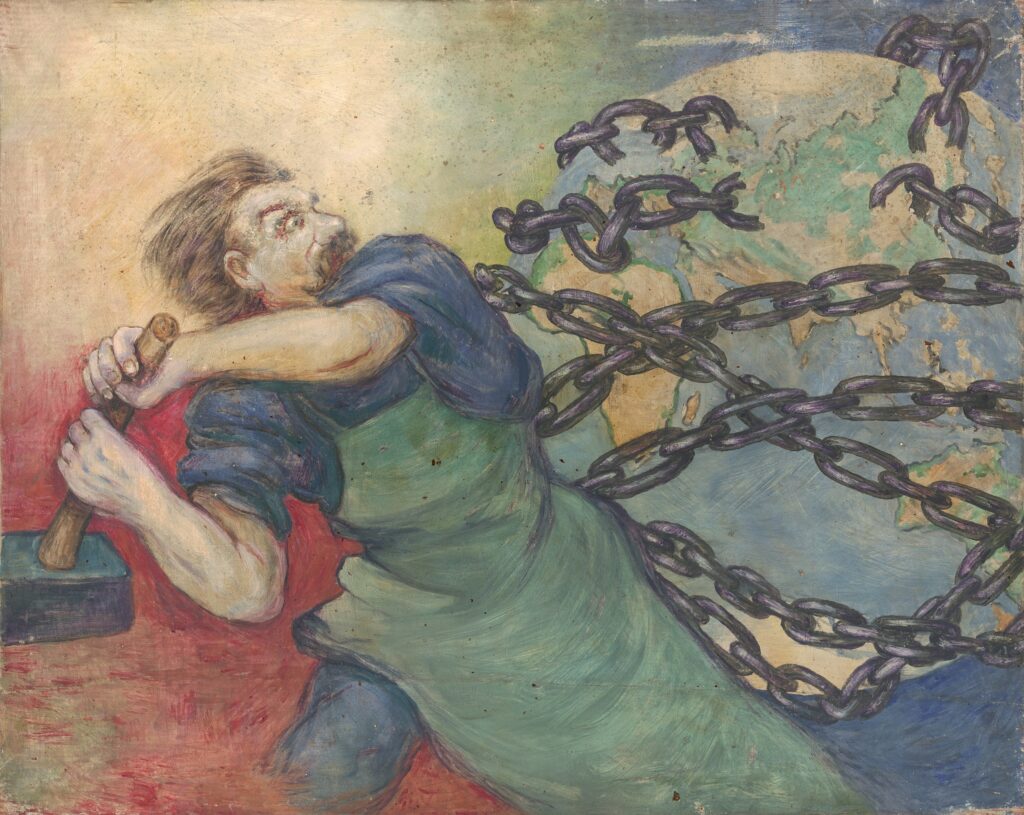

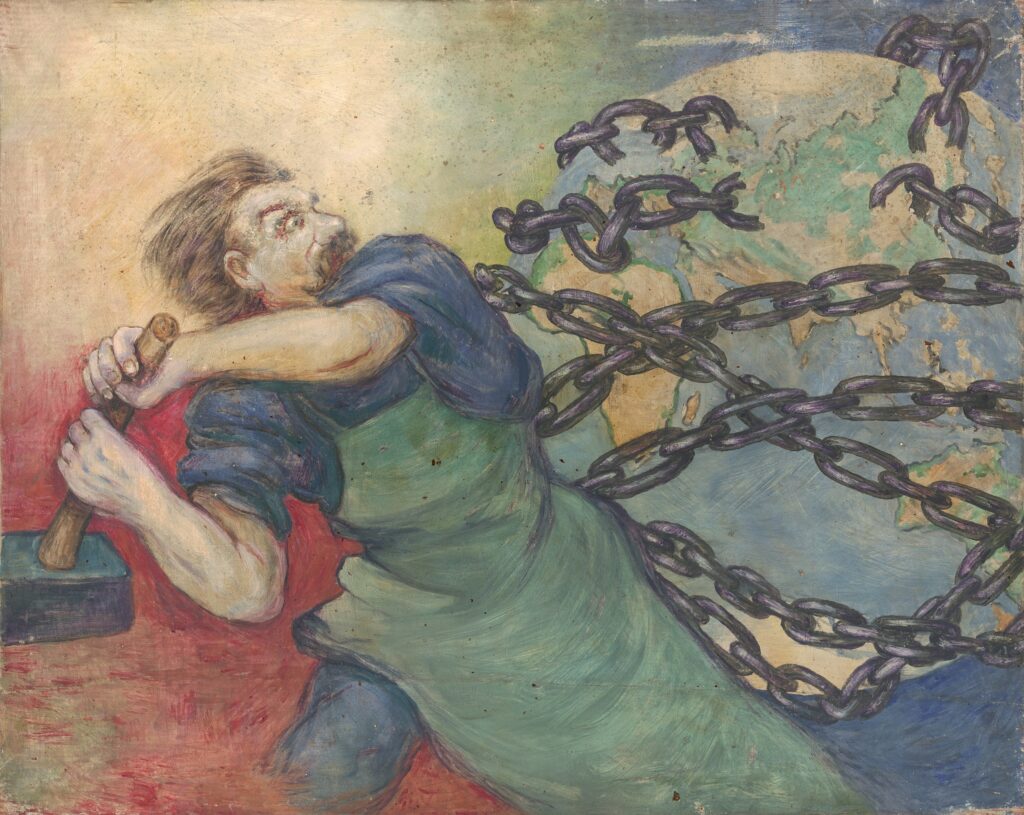

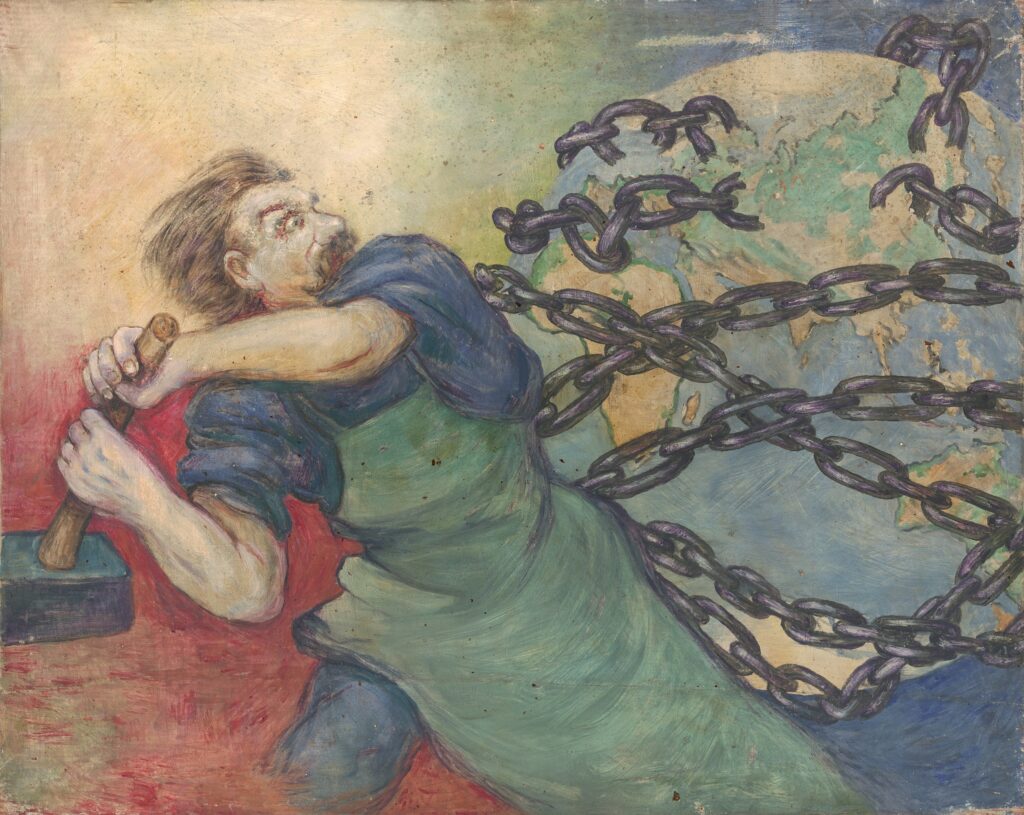

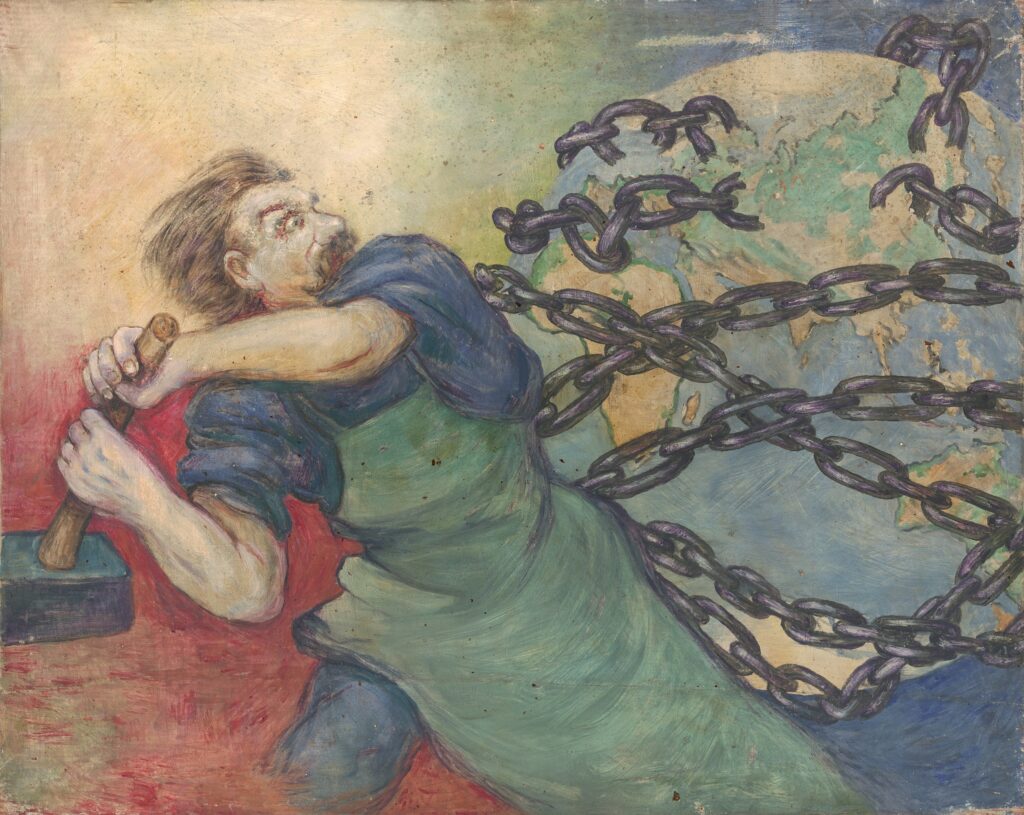

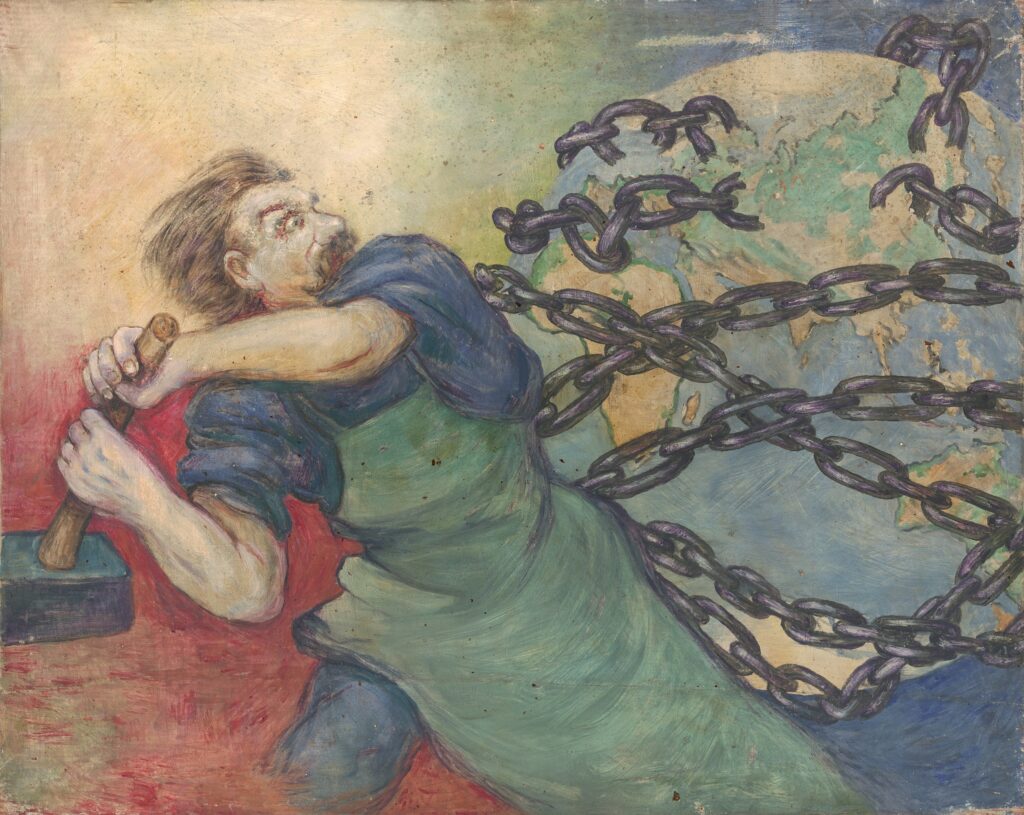

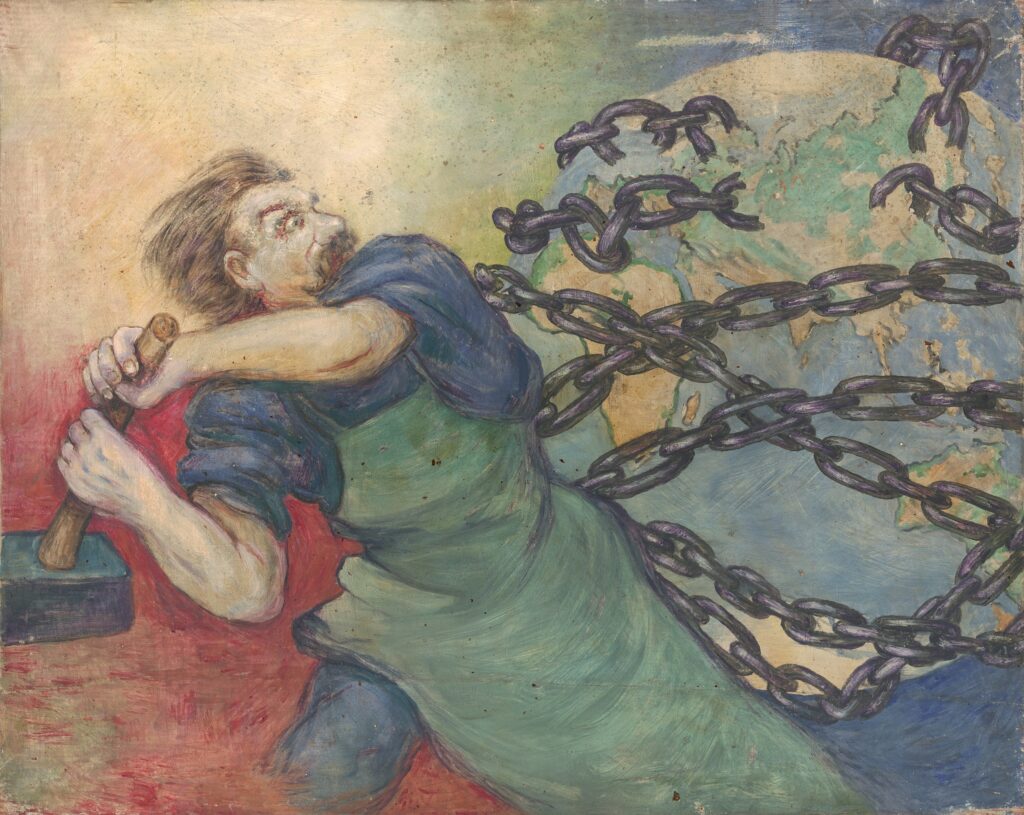

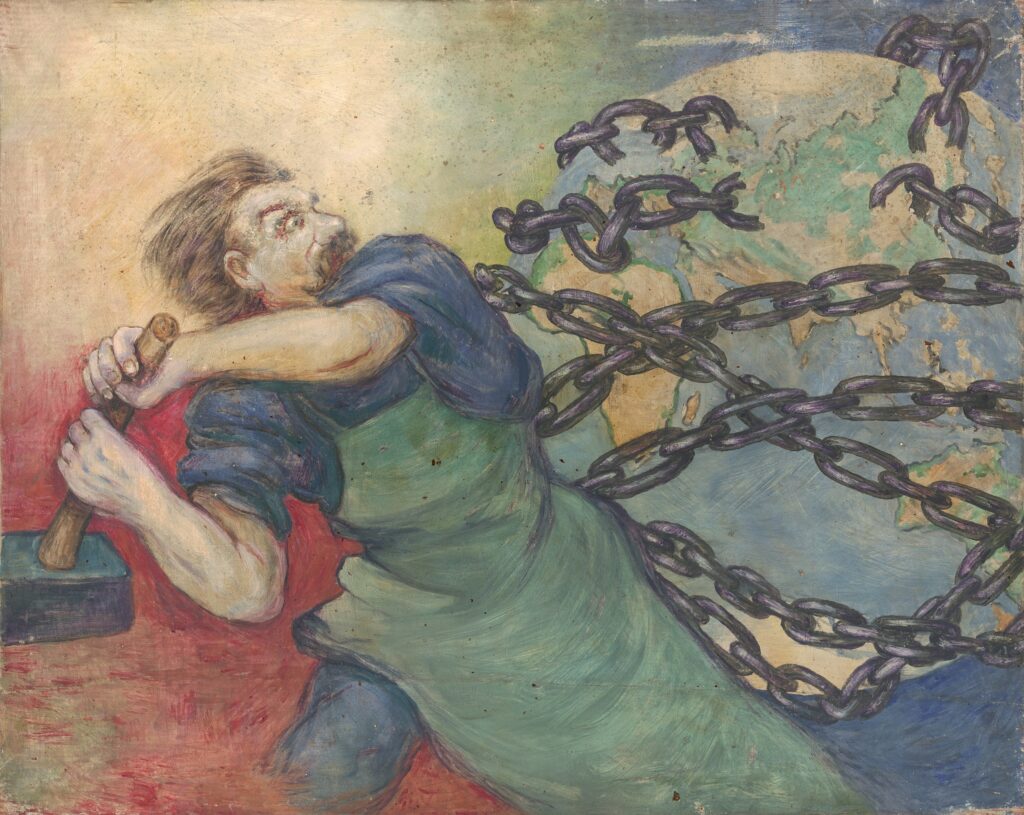

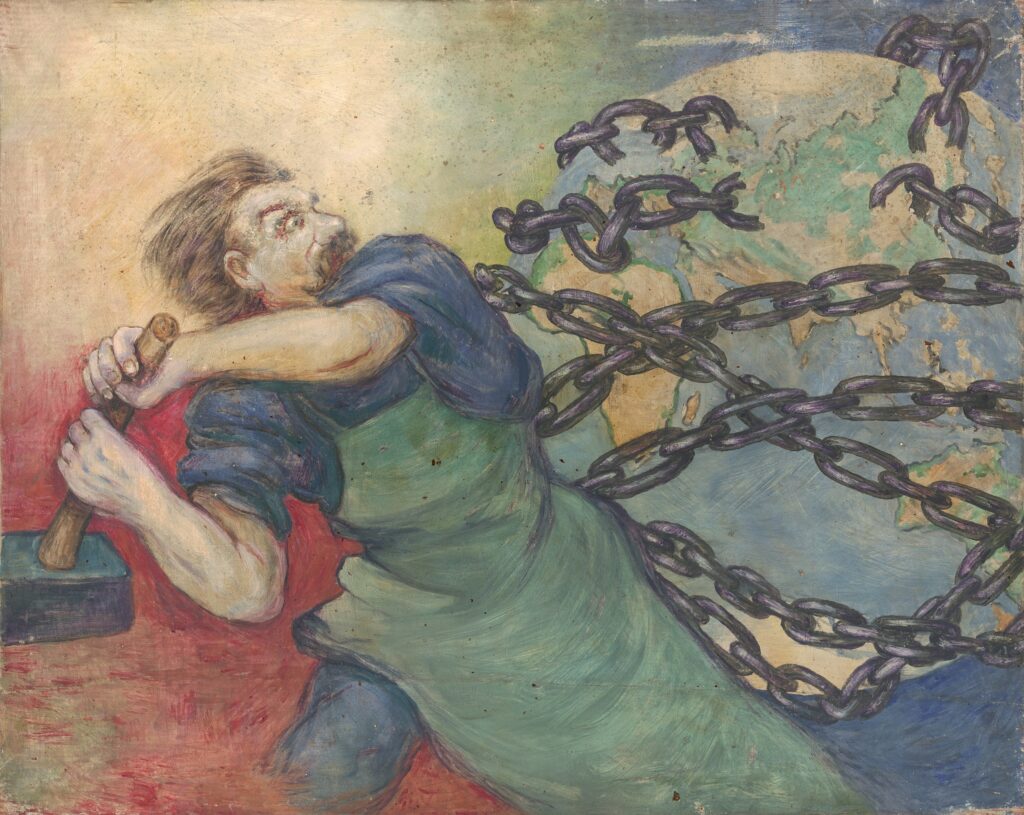

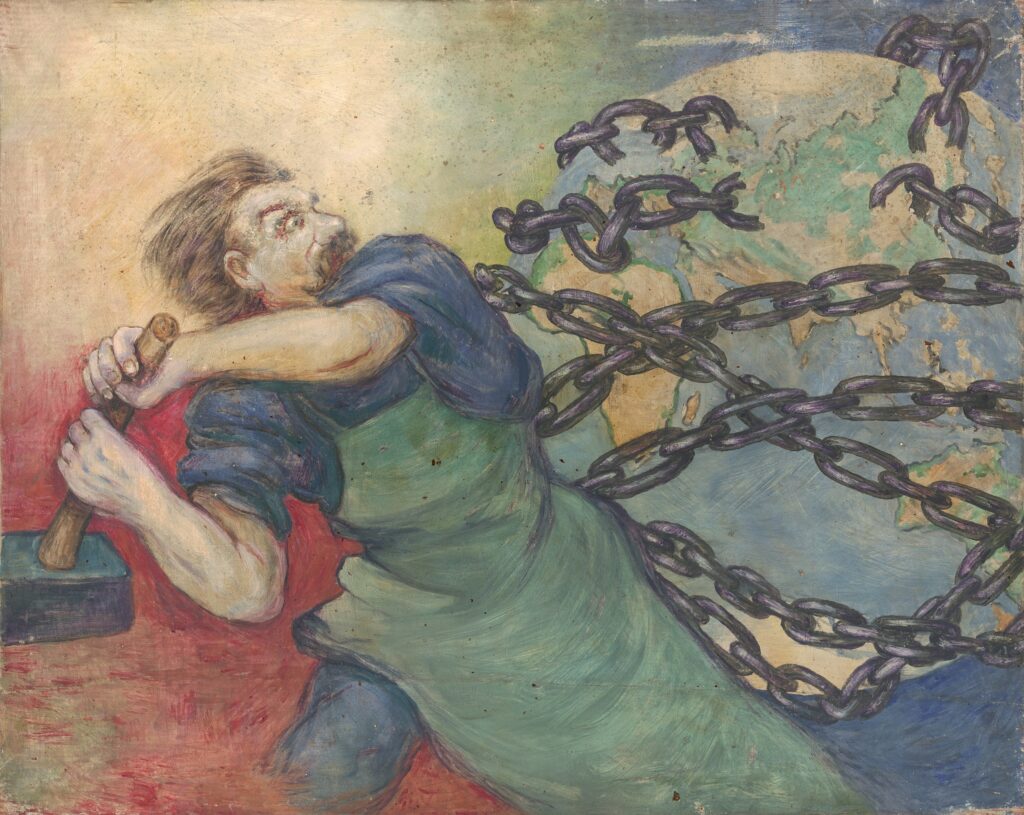

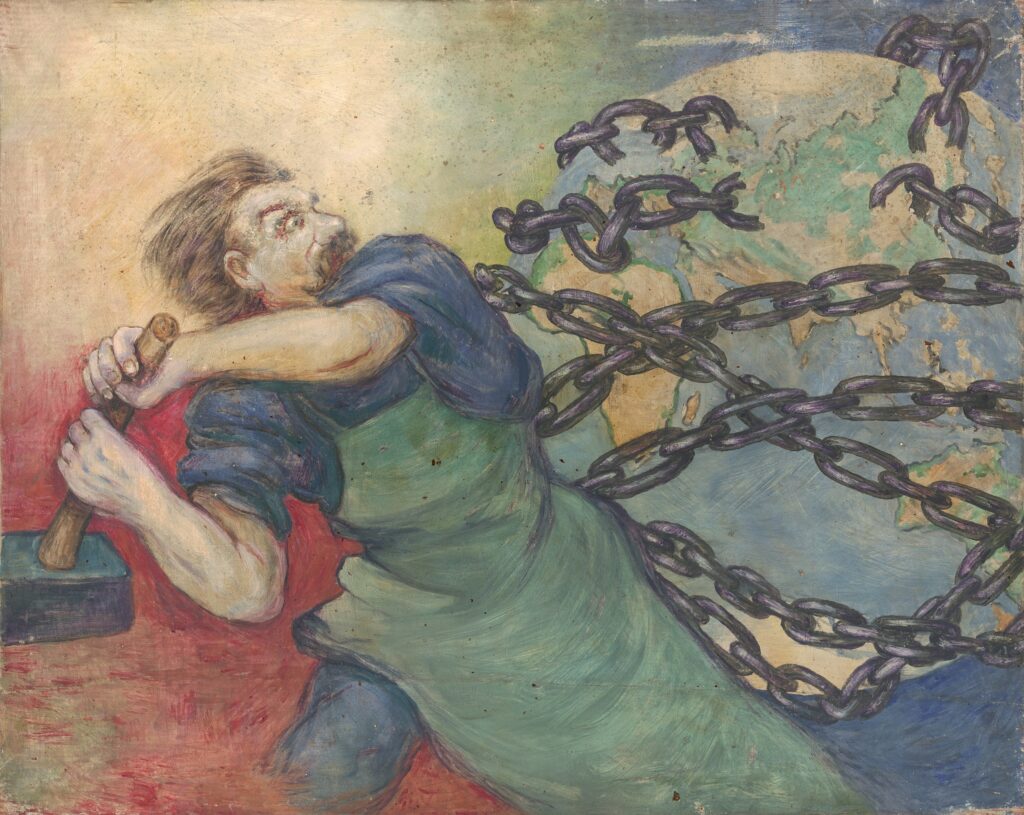

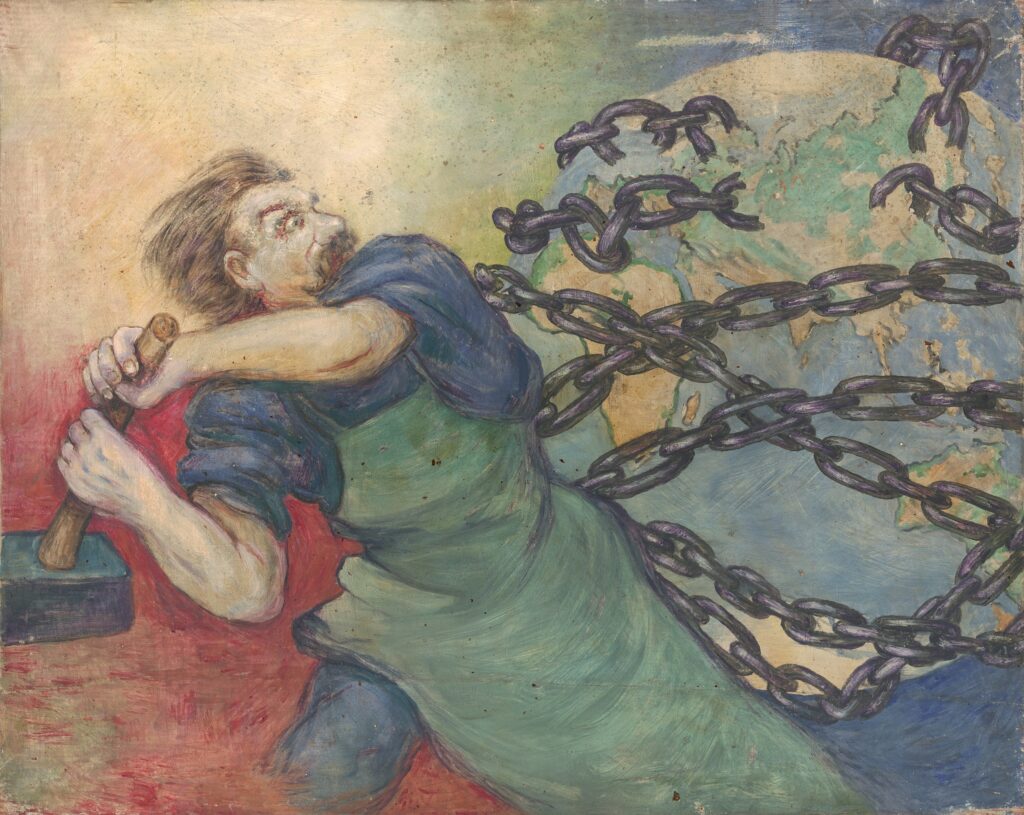

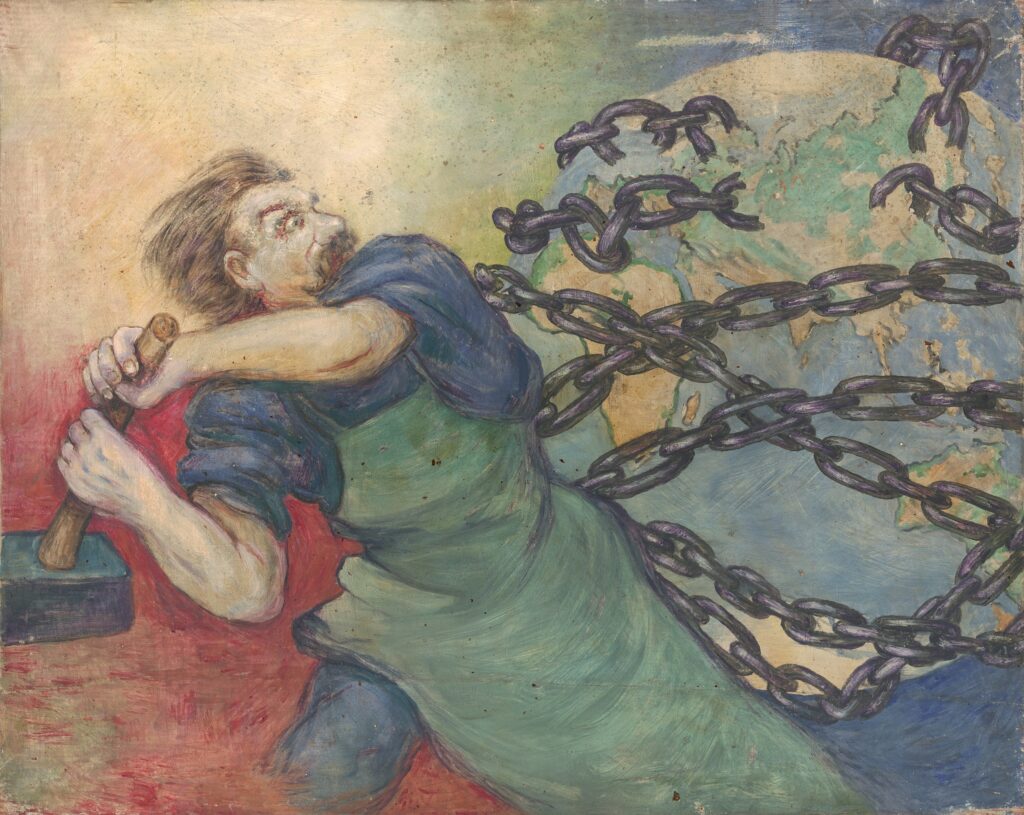

The groundwork for Modernity was laid by the philosophers of the French Enlightenment who influenced the Founding Fathers of the US and the rebels of the French Revolution. The ideals of ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’ in the US and ‘liberty, equality and fraternity’ in France were the clarion call of Modernity. Man was liberated from his oppressors. The monarchies and aristocracies were cast aside, church and state were separated; Modernity was to be an age of Reason.

The worldview of Modernism was characterised by an extravagant optimism and confidence in its own power. Reason was the guiding principle of the age and the novelty of it was intoxicating. With it came a naivete and optimism about the inevitability of Progress in all spheres of life.

This confidence rose to a peak at the end of the 19th and the start of the 20th century. During this time, new technologies that revolutionised life were emerging every year. In the space of a few decades, dozens of world-altering inventions appeared on the scene. For the first time we had bikes, planes and cars, lightbulbs, telephones and the radio. Diseases that once wiped-out entire swaths of the population were now being eradicated.

Science was making rapid leaps forward and it seemed that it was a mere matter of tying up loose ends. In the Long 19th Century the Laws of Thermodynamics were formulated, the Periodic Table was created, and Einstein published his revolutionary papers on relativity.

Even in philosophy there was a fervent excitement about the new study of language and logic. In one of the most typical expressions of Modernism’s self-confidence Ludwig Wittgenstein claimed in 1922 to have dissolved all the problems of philosophy writing that

“The problems are dissolved in the actual sense of the word — like a lump of sugar in water.”

On the social and cultural front it was the age of Democracy when across the world women were getting the vote and slavery was being banned.

But it was also what Matei Călinescu described as “the age of ideology” when people like Marx and Freud tried to give exhaustive accounts of human life. It was the age of Communism, Anarchism and Fascism which each had a grand totalising narrative that proposed a revolution in the ways society is arranged. Modernism had big dreams. It was cresting the wave of progress and, with the inevitable success of that wave, anything seemed possible. It was a time of audacious dreaming.

Postmodernism

By the second half of the 20th century, it became obvious that the vision was a fantasy and with that the conflict of Modernism vs Postmodernism began to gain cultural prominence.

The promises of liberty equality and fraternity, of life liberty and the pursuit of happiness began to appear increasingly hollow with every year. The brutality of the French in Algeria was hardly an embodiment of liberty, equality or fraternity. The soldiers addicted to heroin in Vietnam were far from the Jeffersonian life, liberty and pursuit of happiness. The millions of Vietnamese who even today suffer the downstream effects of the American Agent Orange would undoubtedly agree.

Women had been given the vote but were still ostracised from the workplace and far from true autonomy. The African-American community may have been technically freed from slavery but to call them even second-class citizens in 1950s and 60s America would have been laughable.

As the second half of the twenty-century progressed, it became obvious that the equality and liberty that had been promised in Modernism’s wave of revolutions against the old powers was for many, a horizon that drew no closer.

Dr King: When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men – yes, black men as well as white men – would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked insufficient funds.

The balance of power had shifted but the hands that held it fitted the same demographic profile. But now instead of monarchs and aristocrats, there were tycoons and bankers.

Modernism had taken great leaps forward. But it was not enough. Cynicism began to set in.

The dream of Modernism was dead. And in its wake Postmodernism emerged. This attitude of Postmodernity was everything that Modernity wasn’t. Bye bye to the grand narratives, to the naivete and optimism, to utopian dreams of happy ever after and the glorifying of science.

Postmodernism began to poke holes in the lumbering carcass of Modernism. The dreams of unity that Modernity had dreamed were revealed to be skewed narratives.

This wasn’t just the case with clearly delusional Modernist fantasies like Fascism. It became clear that the glorious promises of Modernity came with a set of terms and conditions – white, male, heterosexual and preferably from a wealthy background.

As the Postmodern age emerged in the 1960s, however, people had enough. Postmodernity was not about fulfilling utopian visions. It was about justice and about equality.

The counterculture of Postmodernity fought for the voices neglected and excluded by Modernity. The women’s movement, Pride, the civil rights movement – all of these Postmodern movements pushed back and held Modernity to account.

The Postmodern philosophers took up the voices of the underdog, of the excluded – of women, of other races, of other sexualities and genders, of prisoners, the insane and the colonised.

The tone of Postmodernity was laced with irony and sarcasm. This was the tone of cynicism that comes with living a world of false promises. It was the tone most suited to meet the betrayal of Modernity.

Modernism vs Postmodernism

Ironically, for all its disdain of Modernity, Postmodernism was fulfilling the dreams of its predecessor. Its fight for justice and equality contained an implicit affirmation of the values of Modernity. There was no whisper of a return to the Medieval values of faith and piety. If anything Postmodernity was characterised by fully embracing the liberty and equality promised by Modernity. Postmodernism was about filling in the cracks in Modernity’s narrative of equality.

But Postmodernity did jettison many core Modernist elements. It dispensed with all grand narratives, with belief in Modernity’s idol Progress. It was critical of science’s prestige and its power in modern life.

Having seen where the arrogant certainty of Modernity had led, Postmodernity was characterised more by the nihilism and relativism that comes with seeing the world from countless perspectives.

And as time has passed and Postmodernism has worked to fulfil the promises that Modernism had reneged on, a new worldview has begun to emerge. This new cultural phase, Metamodernism, takes the irony and manifold perspectives of Postmodernism and integrates them with the optimism and audacity of Modernism. It transcends the conflict of Modernism vs Postmodernism with a synthesis that strives to take the big-picture perspective of Modernity — which Metamodernism finds essential for tackling the major crises facing the world today — while maintaining the depth and biting self-reflection of Postmodernity. This is what we’ll be exploring in the next instalment of The Living Philosophy.

5 Comments

Leave A Comment

Since Habermas wrote these words in 1981, this situation has only become more acute. Now, well into the 21st century, the trenches of the so-called culture war are drawn by the tension of Modernism vs Postmodernism. These two worldviews — as radically different as the Medieval and the Modern — still have much of an overlap.

In this article, we are going to explore the meaning of these two terms — their historical origins, their traits and of course their differences.

“Postmodernity definitely presents itself as Antimodernity.” This statement describes an emotional current of our times which has penetrated all spheres of intellectual life. It has placed on the agenda theories of post-enlightenment, postmodernity, even of posthistory

—Jurgen Habermas, Modernity vs. Postmodernity (1981)

Modernism

The word Modern is a nebulous term that has been used to refer to the contemporary day and age since the 6th century AD. But in the past few decades, a particular time period has come to be identified as Modernity.

The dates of this cultural phase vary with some calling everything after the Middle Ages Modernity; others divide the modern era into three phases:

- Early Modernity: corresponding to the French Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution;

- Classical Modernity: corresponding to the Long 19th Century; and

- Late Modernity: which ended somewhere between 1968 and 1989.

For our purposes here the exact dates do not matter because we’re not really talking about a historical period. Following Foucault’s analysis in his essay What is Enlightenment? we will be treating modernity more “as an attitude than as a period of history.”

And this attitude is most salient in the period known as the Long 19th Century which spanned from the French Revolution in 1789 to the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. This was the time when Modernity had come into its fullness and was the dominant force in the culture.

Foucault identifies a number of traits of Modernity including:

- a questioning or rejection of tradition;

- the prioritising of individualism, freedom and formal equality;

- faith in inevitable social, scientific and technological progress,

- a movement from feudalism toward capitalism and the market economy,

- industrialization and urbanization,

- secularization and,

- the development of the nation-state, representative democracy and public education

The groundwork for Modernity was laid by the philosophers of the French Enlightenment who influenced the Founding Fathers of the US and the rebels of the French Revolution. The ideals of ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’ in the US and ‘liberty, equality and fraternity’ in France were the clarion call of Modernity. Man was liberated from his oppressors. The monarchies and aristocracies were cast aside, church and state were separated; Modernity was to be an age of Reason.

The worldview of Modernism was characterised by an extravagant optimism and confidence in its own power. Reason was the guiding principle of the age and the novelty of it was intoxicating. With it came a naivete and optimism about the inevitability of Progress in all spheres of life.

This confidence rose to a peak at the end of the 19th and the start of the 20th century. During this time, new technologies that revolutionised life were emerging every year. In the space of a few decades, dozens of world-altering inventions appeared on the scene. For the first time we had bikes, planes and cars, lightbulbs, telephones and the radio. Diseases that once wiped-out entire swaths of the population were now being eradicated.

Science was making rapid leaps forward and it seemed that it was a mere matter of tying up loose ends. In the Long 19th Century the Laws of Thermodynamics were formulated, the Periodic Table was created, and Einstein published his revolutionary papers on relativity.

Even in philosophy there was a fervent excitement about the new study of language and logic. In one of the most typical expressions of Modernism’s self-confidence Ludwig Wittgenstein claimed in 1922 to have dissolved all the problems of philosophy writing that

“The problems are dissolved in the actual sense of the word — like a lump of sugar in water.”

On the social and cultural front it was the age of Democracy when across the world women were getting the vote and slavery was being banned.

But it was also what Matei Călinescu described as “the age of ideology” when people like Marx and Freud tried to give exhaustive accounts of human life. It was the age of Communism, Anarchism and Fascism which each had a grand totalising narrative that proposed a revolution in the ways society is arranged. Modernism had big dreams. It was cresting the wave of progress and, with the inevitable success of that wave, anything seemed possible. It was a time of audacious dreaming.

Postmodernism

By the second half of the 20th century, it became obvious that the vision was a fantasy and with that the conflict of Modernism vs Postmodernism began to gain cultural prominence.

The promises of liberty equality and fraternity, of life liberty and the pursuit of happiness began to appear increasingly hollow with every year. The brutality of the French in Algeria was hardly an embodiment of liberty, equality or fraternity. The soldiers addicted to heroin in Vietnam were far from the Jeffersonian life, liberty and pursuit of happiness. The millions of Vietnamese who even today suffer the downstream effects of the American Agent Orange would undoubtedly agree.

Women had been given the vote but were still ostracised from the workplace and far from true autonomy. The African-American community may have been technically freed from slavery but to call them even second-class citizens in 1950s and 60s America would have been laughable.

As the second half of the twenty-century progressed, it became obvious that the equality and liberty that had been promised in Modernism’s wave of revolutions against the old powers was for many, a horizon that drew no closer.

Dr King: When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men – yes, black men as well as white men – would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked insufficient funds.

The balance of power had shifted but the hands that held it fitted the same demographic profile. But now instead of monarchs and aristocrats, there were tycoons and bankers.

Modernism had taken great leaps forward. But it was not enough. Cynicism began to set in.

The dream of Modernism was dead. And in its wake Postmodernism emerged. This attitude of Postmodernity was everything that Modernity wasn’t. Bye bye to the grand narratives, to the naivete and optimism, to utopian dreams of happy ever after and the glorifying of science.

Postmodernism began to poke holes in the lumbering carcass of Modernism. The dreams of unity that Modernity had dreamed were revealed to be skewed narratives.

This wasn’t just the case with clearly delusional Modernist fantasies like Fascism. It became clear that the glorious promises of Modernity came with a set of terms and conditions – white, male, heterosexual and preferably from a wealthy background.

As the Postmodern age emerged in the 1960s, however, people had enough. Postmodernity was not about fulfilling utopian visions. It was about justice and about equality.

The counterculture of Postmodernity fought for the voices neglected and excluded by Modernity. The women’s movement, Pride, the civil rights movement – all of these Postmodern movements pushed back and held Modernity to account.

The Postmodern philosophers took up the voices of the underdog, of the excluded – of women, of other races, of other sexualities and genders, of prisoners, the insane and the colonised.

The tone of Postmodernity was laced with irony and sarcasm. This was the tone of cynicism that comes with living a world of false promises. It was the tone most suited to meet the betrayal of Modernity.

Modernism vs Postmodernism

Ironically, for all its disdain of Modernity, Postmodernism was fulfilling the dreams of its predecessor. Its fight for justice and equality contained an implicit affirmation of the values of Modernity. There was no whisper of a return to the Medieval values of faith and piety. If anything Postmodernity was characterised by fully embracing the liberty and equality promised by Modernity. Postmodernism was about filling in the cracks in Modernity’s narrative of equality.

But Postmodernity did jettison many core Modernist elements. It dispensed with all grand narratives, with belief in Modernity’s idol Progress. It was critical of science’s prestige and its power in modern life.

Having seen where the arrogant certainty of Modernity had led, Postmodernity was characterised more by the nihilism and relativism that comes with seeing the world from countless perspectives.

And as time has passed and Postmodernism has worked to fulfil the promises that Modernism had reneged on, a new worldview has begun to emerge. This new cultural phase, Metamodernism, takes the irony and manifold perspectives of Postmodernism and integrates them with the optimism and audacity of Modernism. It transcends the conflict of Modernism vs Postmodernism with a synthesis that strives to take the big-picture perspective of Modernity — which Metamodernism finds essential for tackling the major crises facing the world today — while maintaining the depth and biting self-reflection of Postmodernity. This is what we’ll be exploring in the next instalment of The Living Philosophy.

5 Comments

-

[…] last week’s article we looked at the difference between the worldviews of Modernity and Postmodernity. Each of these […]

-

[…] is impossible not to be stirred by the vehement passion of Peterson when talking about the Postmodern Neo-Marxists. Whether the feeling stirred is total rage at Peterson or at the so-called Social […]

-

[…] bottom line is that with the emergence of simulation in the postmodern age we have entered, this distinction between the real and the illusory, to use Baudrillard’s term, […]

-

[…] is idolised and demonised as one of the great figureheads of Postmodernism and this polarised reputation is mirrored by the reception of the topic at the centre of his work: […]

-

[…] of truth. One of the reasons why Kuhn was so controversial is that he had little time for this Modernist understanding of truth. We might, following Nietzsche’s analysis in On the Genealogy of Morals […]

Leave A Comment

Since Habermas wrote these words in 1981, this situation has only become more acute. Now, well into the 21st century, the trenches of the so-called culture war are drawn by the tension of Modernism vs Postmodernism. These two worldviews — as radically different as the Medieval and the Modern — still have much of an overlap.

In this article, we are going to explore the meaning of these two terms — their historical origins, their traits and of course their differences.

“Postmodernity definitely presents itself as Antimodernity.” This statement describes an emotional current of our times which has penetrated all spheres of intellectual life. It has placed on the agenda theories of post-enlightenment, postmodernity, even of posthistory

—Jurgen Habermas, Modernity vs. Postmodernity (1981)

Modernism

The word Modern is a nebulous term that has been used to refer to the contemporary day and age since the 6th century AD. But in the past few decades, a particular time period has come to be identified as Modernity.

The dates of this cultural phase vary with some calling everything after the Middle Ages Modernity; others divide the modern era into three phases:

- Early Modernity: corresponding to the French Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution;

- Classical Modernity: corresponding to the Long 19th Century; and

- Late Modernity: which ended somewhere between 1968 and 1989.

For our purposes here the exact dates do not matter because we’re not really talking about a historical period. Following Foucault’s analysis in his essay What is Enlightenment? we will be treating modernity more “as an attitude than as a period of history.”

And this attitude is most salient in the period known as the Long 19th Century which spanned from the French Revolution in 1789 to the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. This was the time when Modernity had come into its fullness and was the dominant force in the culture.

Foucault identifies a number of traits of Modernity including:

- a questioning or rejection of tradition;

- the prioritising of individualism, freedom and formal equality;

- faith in inevitable social, scientific and technological progress,

- a movement from feudalism toward capitalism and the market economy,

- industrialization and urbanization,

- secularization and,

- the development of the nation-state, representative democracy and public education

The groundwork for Modernity was laid by the philosophers of the French Enlightenment who influenced the Founding Fathers of the US and the rebels of the French Revolution. The ideals of ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’ in the US and ‘liberty, equality and fraternity’ in France were the clarion call of Modernity. Man was liberated from his oppressors. The monarchies and aristocracies were cast aside, church and state were separated; Modernity was to be an age of Reason.

The worldview of Modernism was characterised by an extravagant optimism and confidence in its own power. Reason was the guiding principle of the age and the novelty of it was intoxicating. With it came a naivete and optimism about the inevitability of Progress in all spheres of life.

This confidence rose to a peak at the end of the 19th and the start of the 20th century. During this time, new technologies that revolutionised life were emerging every year. In the space of a few decades, dozens of world-altering inventions appeared on the scene. For the first time we had bikes, planes and cars, lightbulbs, telephones and the radio. Diseases that once wiped-out entire swaths of the population were now being eradicated.

Science was making rapid leaps forward and it seemed that it was a mere matter of tying up loose ends. In the Long 19th Century the Laws of Thermodynamics were formulated, the Periodic Table was created, and Einstein published his revolutionary papers on relativity.

Even in philosophy there was a fervent excitement about the new study of language and logic. In one of the most typical expressions of Modernism’s self-confidence Ludwig Wittgenstein claimed in 1922 to have dissolved all the problems of philosophy writing that

“The problems are dissolved in the actual sense of the word — like a lump of sugar in water.”

On the social and cultural front it was the age of Democracy when across the world women were getting the vote and slavery was being banned.

But it was also what Matei Călinescu described as “the age of ideology” when people like Marx and Freud tried to give exhaustive accounts of human life. It was the age of Communism, Anarchism and Fascism which each had a grand totalising narrative that proposed a revolution in the ways society is arranged. Modernism had big dreams. It was cresting the wave of progress and, with the inevitable success of that wave, anything seemed possible. It was a time of audacious dreaming.

Postmodernism

By the second half of the 20th century, it became obvious that the vision was a fantasy and with that the conflict of Modernism vs Postmodernism began to gain cultural prominence.

The promises of liberty equality and fraternity, of life liberty and the pursuit of happiness began to appear increasingly hollow with every year. The brutality of the French in Algeria was hardly an embodiment of liberty, equality or fraternity. The soldiers addicted to heroin in Vietnam were far from the Jeffersonian life, liberty and pursuit of happiness. The millions of Vietnamese who even today suffer the downstream effects of the American Agent Orange would undoubtedly agree.

Women had been given the vote but were still ostracised from the workplace and far from true autonomy. The African-American community may have been technically freed from slavery but to call them even second-class citizens in 1950s and 60s America would have been laughable.

As the second half of the twenty-century progressed, it became obvious that the equality and liberty that had been promised in Modernism’s wave of revolutions against the old powers was for many, a horizon that drew no closer.

Dr King: When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men – yes, black men as well as white men – would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked insufficient funds.

The balance of power had shifted but the hands that held it fitted the same demographic profile. But now instead of monarchs and aristocrats, there were tycoons and bankers.

Modernism had taken great leaps forward. But it was not enough. Cynicism began to set in.

The dream of Modernism was dead. And in its wake Postmodernism emerged. This attitude of Postmodernity was everything that Modernity wasn’t. Bye bye to the grand narratives, to the naivete and optimism, to utopian dreams of happy ever after and the glorifying of science.

Postmodernism began to poke holes in the lumbering carcass of Modernism. The dreams of unity that Modernity had dreamed were revealed to be skewed narratives.

This wasn’t just the case with clearly delusional Modernist fantasies like Fascism. It became clear that the glorious promises of Modernity came with a set of terms and conditions – white, male, heterosexual and preferably from a wealthy background.

As the Postmodern age emerged in the 1960s, however, people had enough. Postmodernity was not about fulfilling utopian visions. It was about justice and about equality.

The counterculture of Postmodernity fought for the voices neglected and excluded by Modernity. The women’s movement, Pride, the civil rights movement – all of these Postmodern movements pushed back and held Modernity to account.

The Postmodern philosophers took up the voices of the underdog, of the excluded – of women, of other races, of other sexualities and genders, of prisoners, the insane and the colonised.

The tone of Postmodernity was laced with irony and sarcasm. This was the tone of cynicism that comes with living a world of false promises. It was the tone most suited to meet the betrayal of Modernity.

Modernism vs Postmodernism

Ironically, for all its disdain of Modernity, Postmodernism was fulfilling the dreams of its predecessor. Its fight for justice and equality contained an implicit affirmation of the values of Modernity. There was no whisper of a return to the Medieval values of faith and piety. If anything Postmodernity was characterised by fully embracing the liberty and equality promised by Modernity. Postmodernism was about filling in the cracks in Modernity’s narrative of equality.

But Postmodernity did jettison many core Modernist elements. It dispensed with all grand narratives, with belief in Modernity’s idol Progress. It was critical of science’s prestige and its power in modern life.

Having seen where the arrogant certainty of Modernity had led, Postmodernity was characterised more by the nihilism and relativism that comes with seeing the world from countless perspectives.

And as time has passed and Postmodernism has worked to fulfil the promises that Modernism had reneged on, a new worldview has begun to emerge. This new cultural phase, Metamodernism, takes the irony and manifold perspectives of Postmodernism and integrates them with the optimism and audacity of Modernism. It transcends the conflict of Modernism vs Postmodernism with a synthesis that strives to take the big-picture perspective of Modernity — which Metamodernism finds essential for tackling the major crises facing the world today — while maintaining the depth and biting self-reflection of Postmodernity. This is what we’ll be exploring in the next instalment of The Living Philosophy.

5 Comments

-

[…] last week’s article we looked at the difference between the worldviews of Modernity and Postmodernity. Each of these […]

-

[…] is impossible not to be stirred by the vehement passion of Peterson when talking about the Postmodern Neo-Marxists. Whether the feeling stirred is total rage at Peterson or at the so-called Social […]

-

[…] bottom line is that with the emergence of simulation in the postmodern age we have entered, this distinction between the real and the illusory, to use Baudrillard’s term, […]

-

[…] is idolised and demonised as one of the great figureheads of Postmodernism and this polarised reputation is mirrored by the reception of the topic at the centre of his work: […]

-

[…] of truth. One of the reasons why Kuhn was so controversial is that he had little time for this Modernist understanding of truth. We might, following Nietzsche’s analysis in On the Genealogy of Morals […]

[…] last week’s article we looked at the difference between the worldviews of Modernity and Postmodernity. Each of these […]

[…] is impossible not to be stirred by the vehement passion of Peterson when talking about the Postmodern Neo-Marxists. Whether the feeling stirred is total rage at Peterson or at the so-called Social […]

[…] bottom line is that with the emergence of simulation in the postmodern age we have entered, this distinction between the real and the illusory, to use Baudrillard’s term, […]

[…] is idolised and demonised as one of the great figureheads of Postmodernism and this polarised reputation is mirrored by the reception of the topic at the centre of his work: […]

[…] of truth. One of the reasons why Kuhn was so controversial is that he had little time for this Modernist understanding of truth. We might, following Nietzsche’s analysis in On the Genealogy of Morals […]