It is impossible not to be stirred by the vehement passion of Peterson when talking about the Postmodern Neo-Marxists. Whether the feeling stirred is total rage at Peterson or at the so-called Social Justice Warriors depends of course on your own political leanings.

For those of us who are partial to a Jungian brew, this should have immediately stirred our suspicions. Because now looking back at it, it seems patently obvious that what we are seeing is a dance of the archetypal Shadow. Peterson’s narrative about the Postmodern Neo-Marxists goes, as we will see, beyond all reasonable bounds into the realm of conspiracy theory. It is not simple dismay with a cultural trend, it is the belief that this is a nefarious plot to overwhelm everything we hold dear.

When you put it like that it’s hard not to see Peterson’s Shadow. It’s written everywhere in this discourse. It makes a strawman out of its opponents and makes the French Continental philosophers into scapegoats for the decline of the West.

And what’s so perfect about it, is that Peterson’s discourse constellates the Shadow of the so-called Social Justice Warriors. They see an old privileged white man dismissing their oppression and calling them ungrateful for not loving the world they live in.

Carl Jung would have had a field day.

In an age ruled by controversy-loving algorithms Peterson’s Postmodern Neo-Marxist discourse was like catnip cut with crack cocaine. And it’s about time we pierced the veil.

In this edition then we are going to explore how Postmodern Neo-Marxism is a manifestation of Jordan Peterson’s Jungian Shadow and more specifically how Michel Foucault represents his bête noir.

To do this we’re first going to briefly reconstruct Peterson’s argument which comprises three main pieces:

1. The relativism of Postmodernism,

2. The Neo-Marxist “sleight of hand” and

3. The attack on Enlightenment values.

Once we’ve done that we will look at how Peterson’s argument is a manifestation of his Shadow in the form of an elaborate conspiracy theory that invokes the American psyche’s worst nightmares: Communism and an attack on the Enlightenment values of its Founding Fathers.

We are also going to look at why Peterson’s Shadow has been so explosive firstly because it is a collective shadow of one group in society and secondly because it powerfully constellates the complementary Shadow of the so-called Social Justice Warriors. In short it is a cocktail of Shadow psychology jacked up on algorithm juice and fuelled by mob mentality.

Peterson’s Argument

I first came across Jordan Peterson on Joe Rogan’s podcast a few months after his first appearance and I fell in love with him immediately. As a diehard lover of Nietzsche and Jung, Peterson’s lectures are nothing short of intellectual porn for me.

The only aspect of his work that I’m not keen on however happens to be the reason I and so many others discovered him. While I am sympathetic to many of Peterson’s points in the context of the “Culture Wars”, his main argument is built on what can only be described as a conspiracy theory.

As fans of JP, we have heard the Postmodern Neo-Marxist spiel a hundred times before but I’m going to try here to reconstruct the key points of his overall argument so that we all know what we’re talking about.

For Peterson there are three critical aspects to the Postmodern Neo-Marxist framework: there’s the Postmodernist element, the Neo-Marxist element and their target: Western society’s Enlightenment values.

1. The Postmodernist strain

The first part then is the Postmodernist element. Later on we’re going to touch briefly on the slipperiness of the term Postmodernist but for now we’ll take it for granted and focus on Peterson’s characterisation of this movement which for all intents and purposes is made up of Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault in Peterson’s eyes.

Other than one passing reference to Lyotard, another to Sartre and a few to Lacan, Peterson never really discusses any other philosophers of this era in any depth. His targets are Derrida and Foucault.

Peterson identifies one doctrine above all with this tradition and that is relativism.

JP usually frames this in terms of Derrida’s “there is nothing outside the text” basically the idea that when reading any text there are an infinite number of interpretations that can be brought to bear on it. But that is not all — none of these interpretations can be privileged above the others.

And this is just the beginning because the world is infinitely more complex than any individual text and so any interpretation we make of the world is only going to be one interpretation among many. There is no canonical interpretation — no final and ultimate truth.

This relativism is the first aspect of Peterson’s Postmodern Neo-Marxist equation. The second element is the Neo-Marxist piece.

2. The Neo-Marxist strain

Peterson argues that in the 1960s and 70s, the Postmodern philosophers pulled off what he repeatedly calls a “sleight of hand”.

The argument goes something like this: French philosophy in the mid-20th century was riddled with Marxism. But in the 1960s and 70s, as the horrors of the Gulags and of Mao’s Cultural Revolution began to emerge, Communism became an untenable position.

So with Communism now untenable, the French philosophers who were so fond of Karl Marx were presented with a major problem: what to do about Marxism?

And so they found a solution: they performed a sleight of hand that allowed them to not only keep their Marxist philosophy but in doing so devise an even more nefarious plan where they, like any good villain, try to take over the world.

They swapped out Marxism’s narrative of history being a neverending class struggle between the bourgeoise and the proletariat, and replaced it with a slightly more abstracted version.

The Postmodernists parted with Marxism’s economic version of the oppressor/oppressed and replaced it with a group identity-based model of oppressor/oppressed.

And with that done, the French philosophy ostensibly left behind Marxism and instead fomented a different type of revolution. Classical Marxism had been reborn as Identity Politics. But that’s not all.

This is where the argument — if it hadn’t already — enters the unambiguous waters of conspiracy theory. Peterson seems to argue that these Postmodern Neo-Marxists were not merely teaching their beliefs but that there some sort of method to it all.

Instead of the Marxists taking over the world through a violent revolution, the Neo-Marxist or “Cultural Marxists” take over society by capturing the education system. This isn’t an accident but a plot.

3. The attack on Enlightenment values

And that brings us onto the third element of Peterson’s argument: the target of the Postmodern Neo-Marxists. And true to form, these pesky Postmodern Neo-Marxists target the same thing all Shadow villains go after: everything we hold dear.

The Postmodern Neo-Marxists want to deconstruct everything established since the Enlightenment — rationality, empiricism, science, clarity of mind, dialogue, the idea of the individual. Just as Communism wanted to destroy the capitalist system, the Postmodern Neo-Marxists want to dismantle the Enlightenment values of the West.

Counterargument

We have our bete noire and say with the old Pharisee: “God, I thank thee, that I am not as other men are.”

We don’t want to know that we are the “other men.”

— Carl Jung, ETH Lecture 27 Jan 1939

There are many weak points to Peterson’s argument. First off it should be pointed out that Peterson imbibed most of this theory — seemingly unquestioningly — from the poorly referenced work of Stephen Hicks. For a breakdown of the many many scholarly errors in Hicks’s book I’d highly recommend Jonas Ceika’s video dissection.

While my focus is predominantly on the psychology of Peterson, I think it is worth mentioning a couple of broader points beforehand.

Firstly the term postmodernist is not nearly as uncontroversial as it seems. It’s worth remembering that Postmodernism isn’t a term that these philosophers applied to themselves.

And so it is a slippery term that we must be careful with. These philosophers don’t fall into such a natural grouping together that we can talk about their views as a homogenous whole.

When Peterson talks about the focus of Postmodernism being a scepticism of grand narratives you have to remember this was Lyotard’s characterisation of Postmodernity and not a manifesto written by a group of philosophers who called themselves Postmodernists.

Secondly the collapse of Marxism is not nearly as dramatic as Peterson makes it out to be. It was very far from becoming a taboo position.

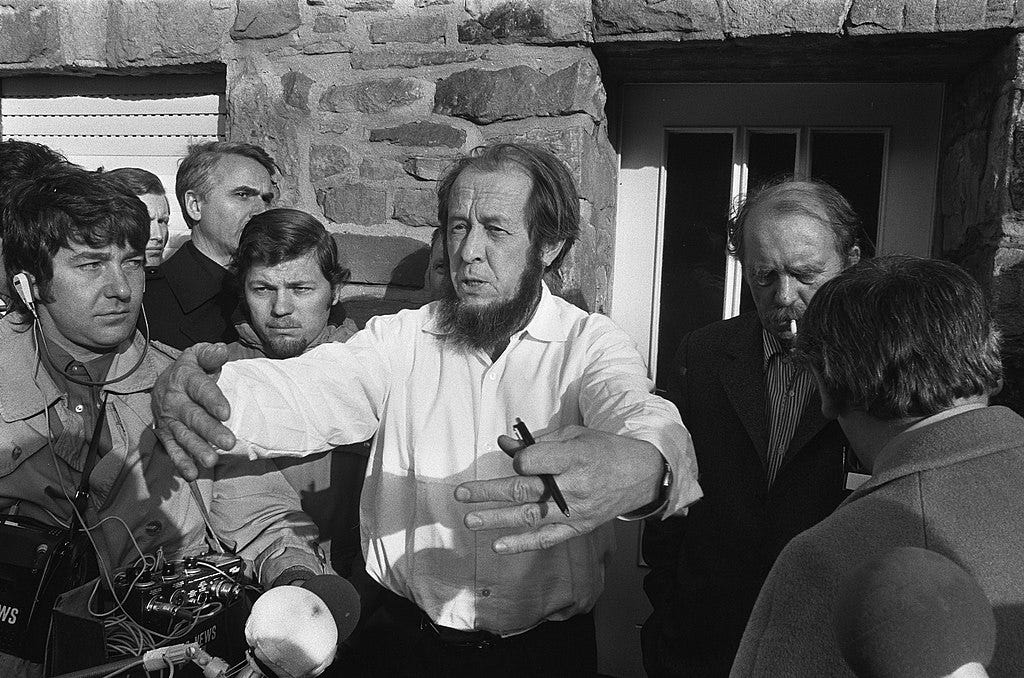

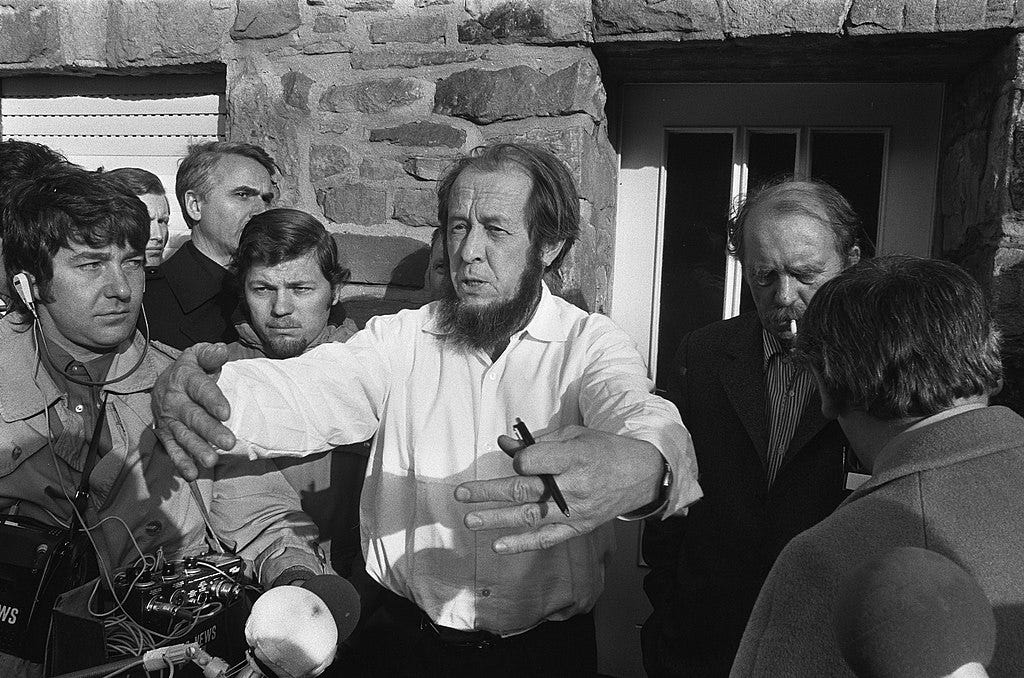

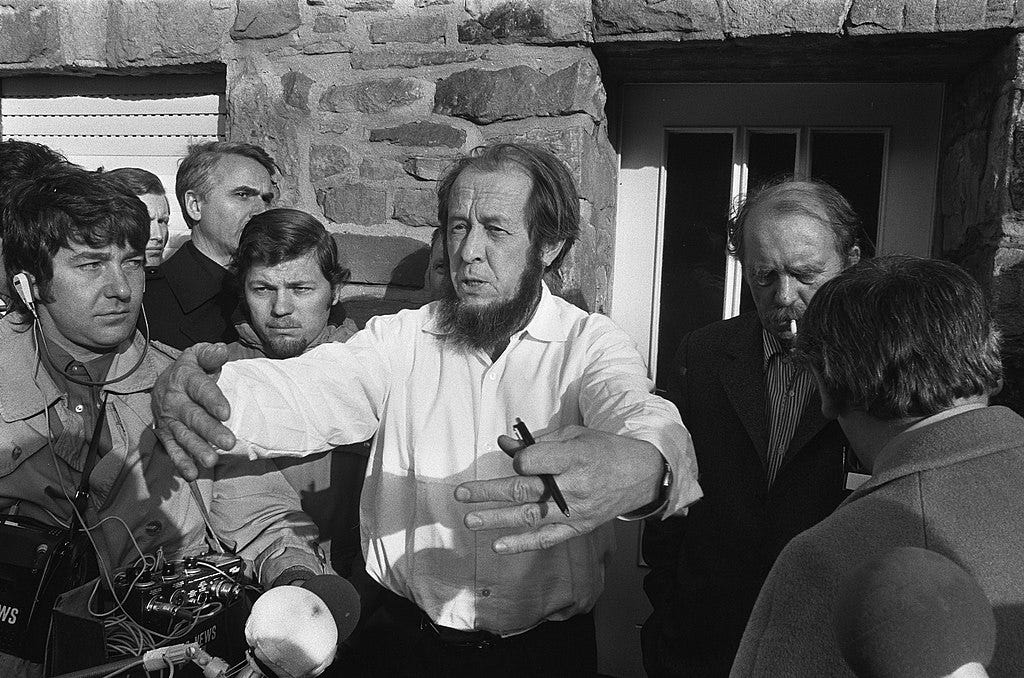

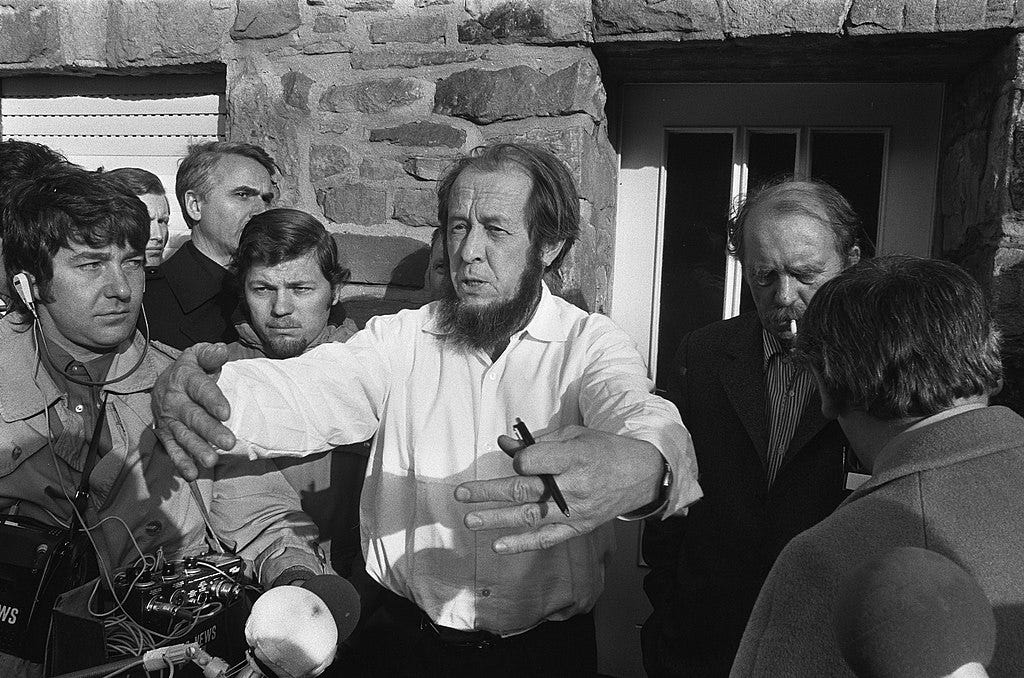

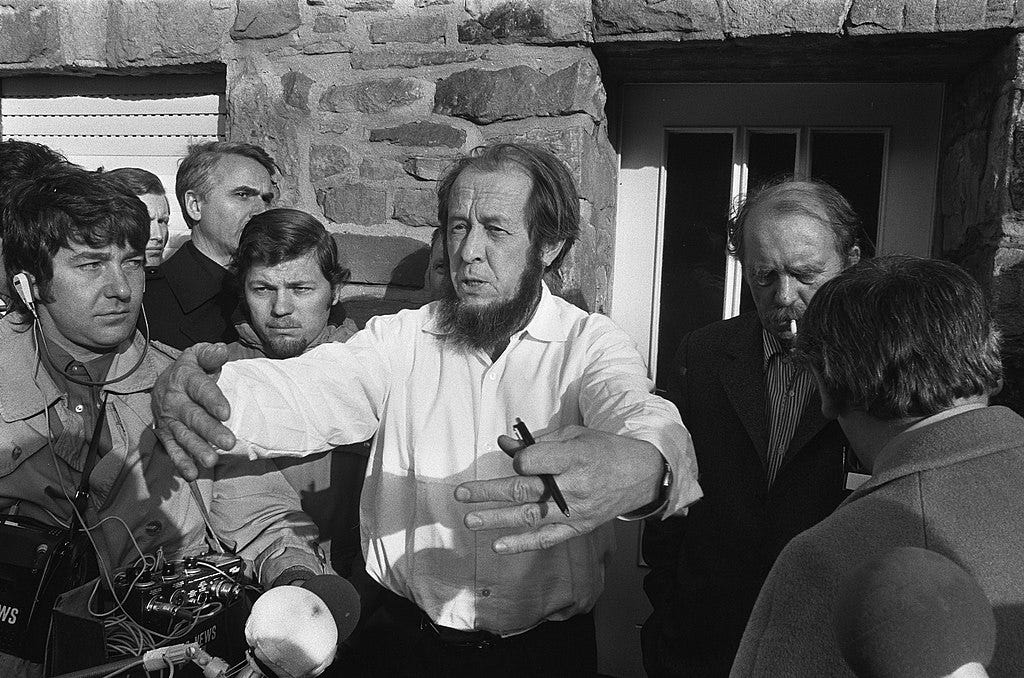

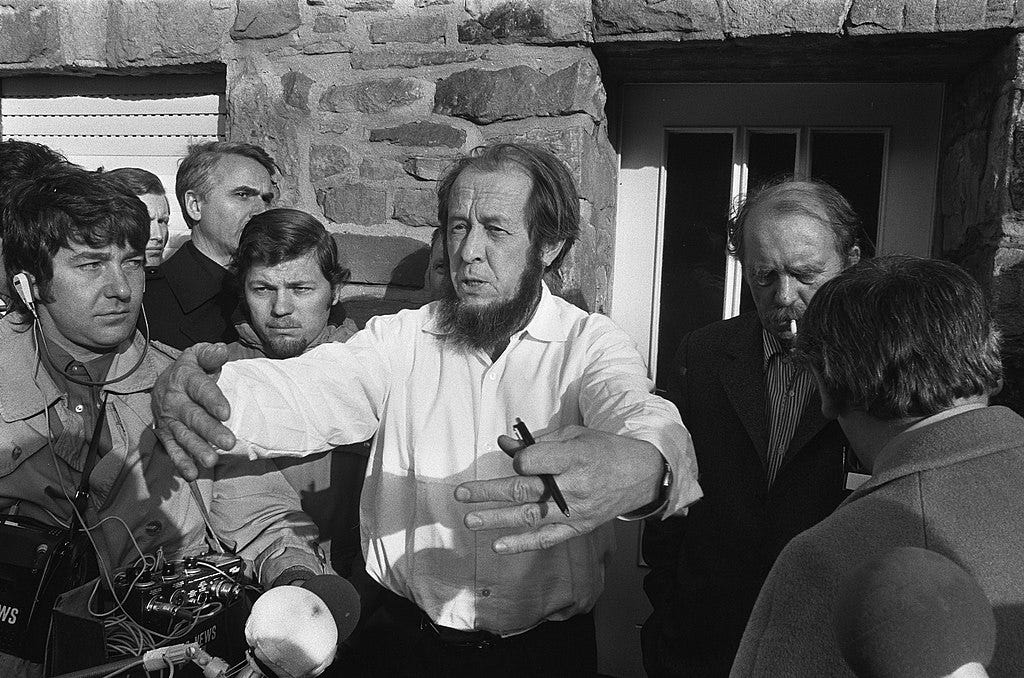

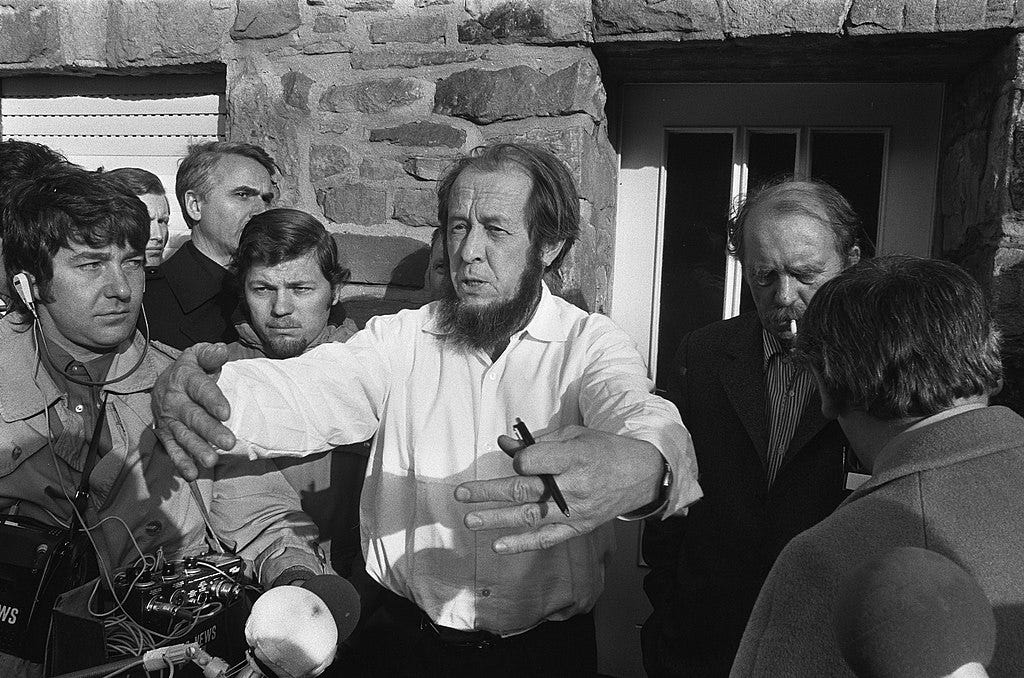

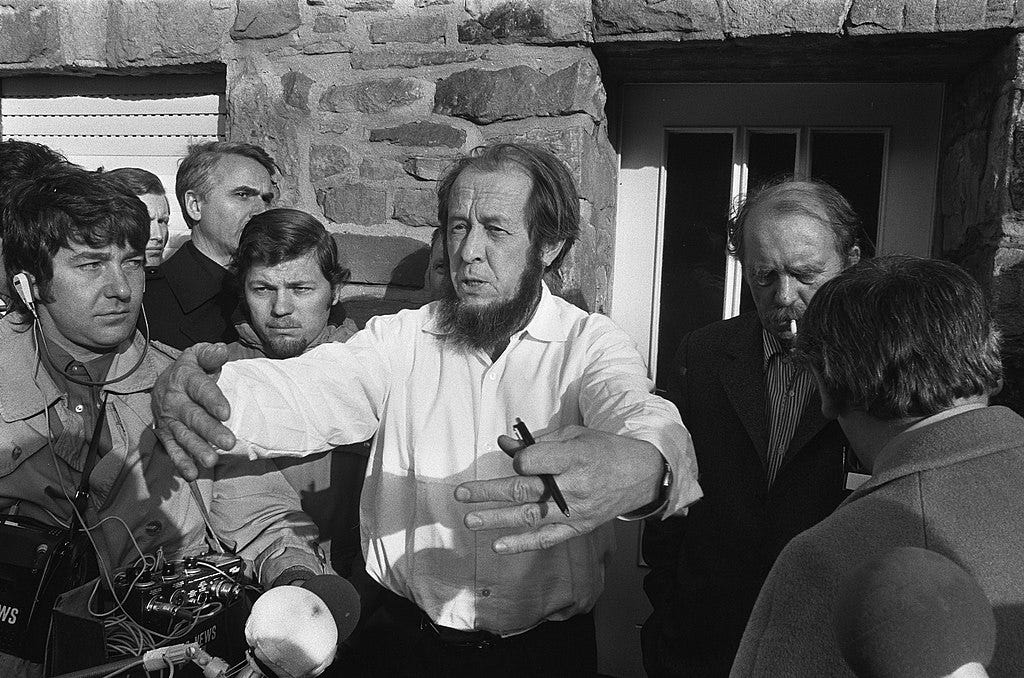

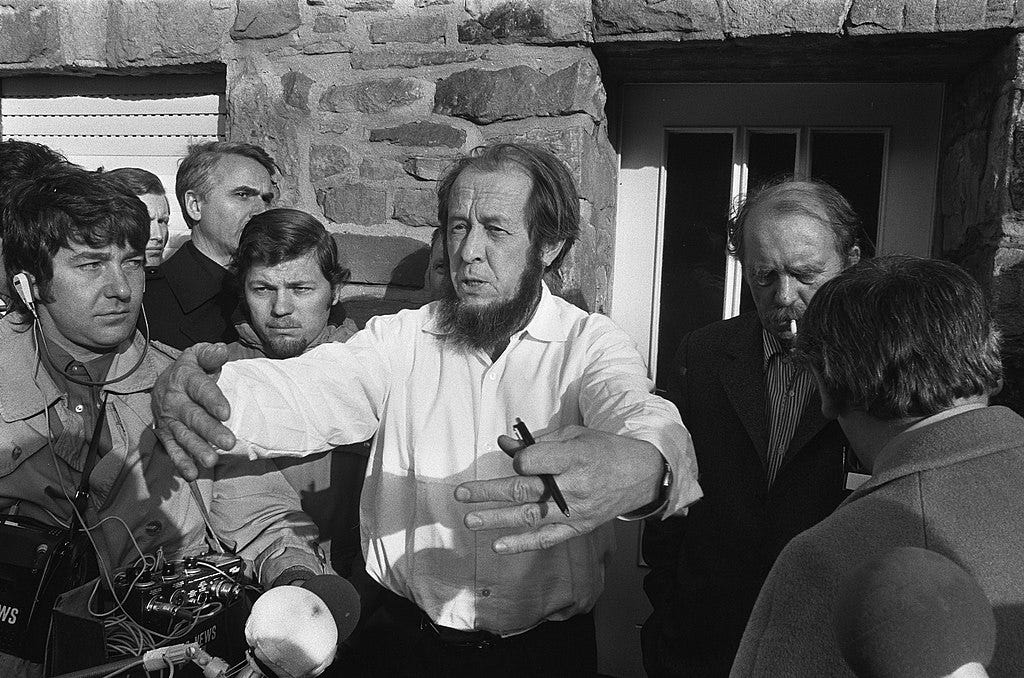

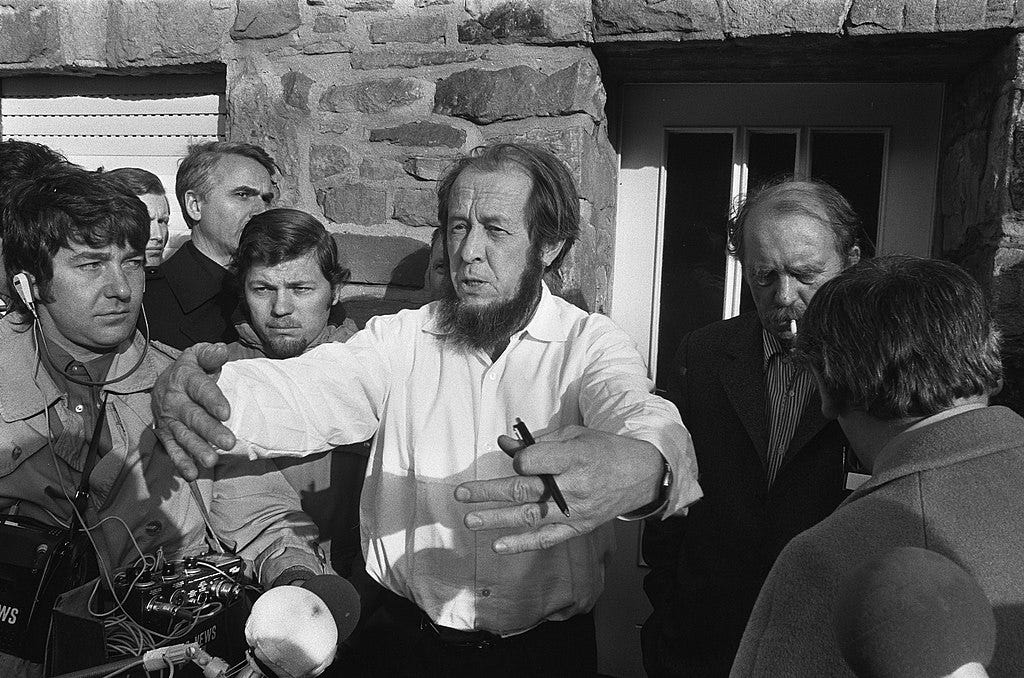

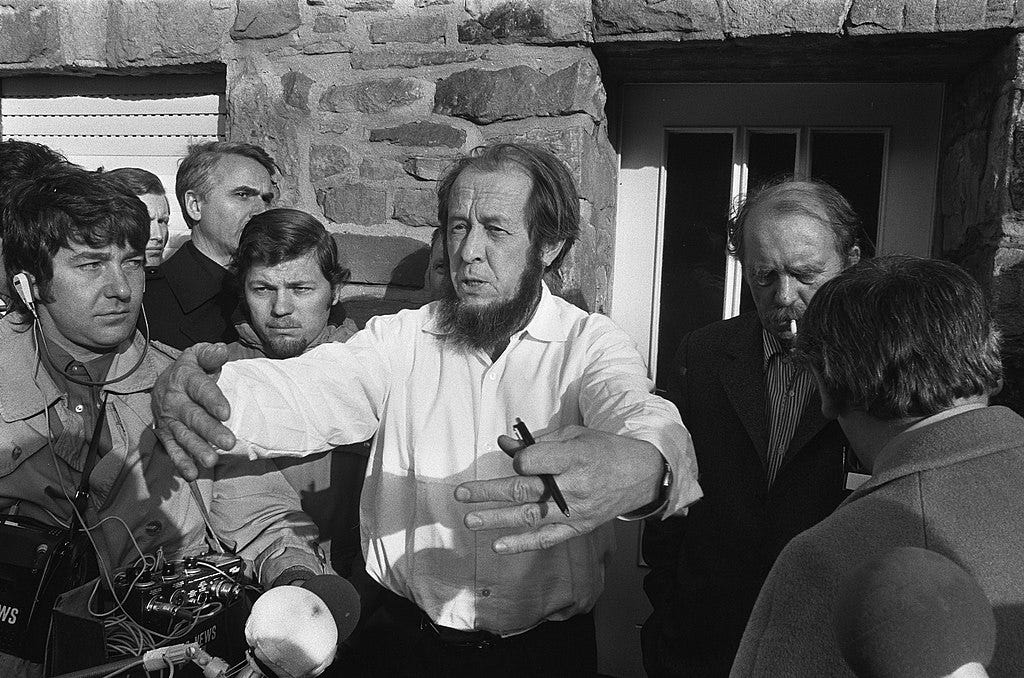

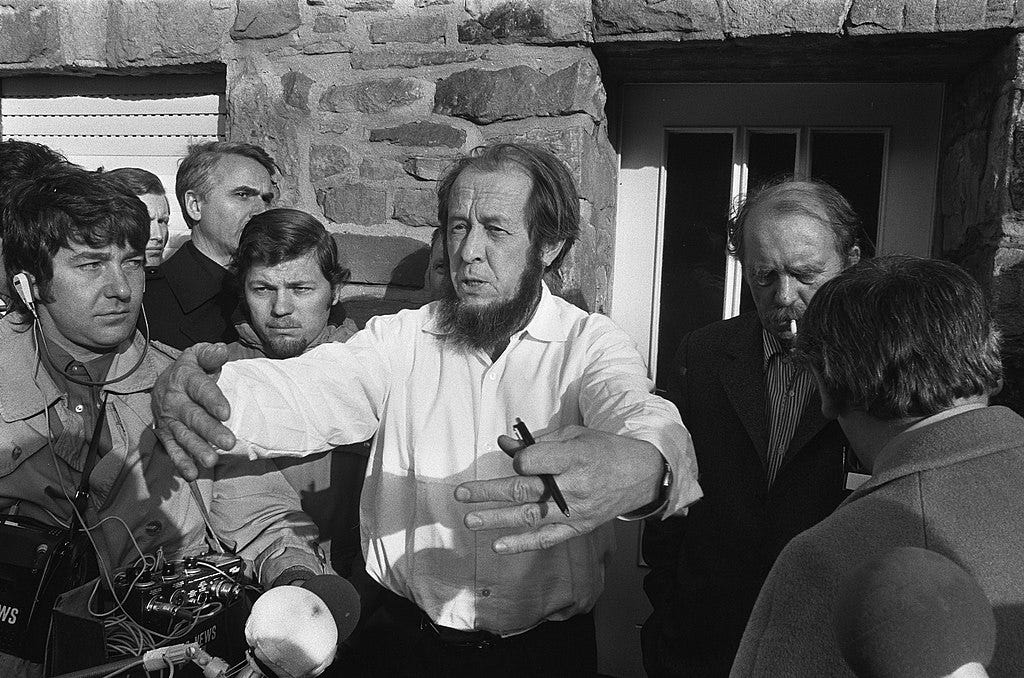

Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago — which Peterson identifies as the catalyst for the downfall of Communism — was published in 1974. In the next election in 1978 the French Communist party received its highest number of votes ever. In total they got 5.8 million votes up from 5 million in 1973. That’s more than 20% of the French public voting for the Communist party. And while Communism’s star was waning, the Communist candidate for the 1981 French Presidency still received 4.4 million votes. That’s very far from being an untenable position.

A third point worth noting is Peterson’s characterisation of Derrida and Foucault as being fervent Marxists. Anyone who has studied either thinker knows this to be patently false.

Derrida is perhaps the least political of all the so-called Postmodernist philosophers. He finally broke his silence with 1993’s Spectres of Marx but this is much more a dismissal of Marxism and a transcendence of it than anything else.

Foucault on the other hand was the French philosopher most known for savaging Marx and Marxists. He became a member of the Communist Party for a year when he first entered university but unlike his classmates he left disgusted with Marxism. This was in the 1940s, long before anything about the Gulags or about Mao. In 1975, when Foucault was protesting the impending execution of 11 Spaniards without trial by the Fascist regime of General Franco, a young militant asked Foucault if he would give a talk to his group about Marx. Foucault snapped at him:

“Don’t talk to me about Marx any more! I never want to hear anything about that man again. Ask someone whose job it is. Someone paid to do it. Ask the Marxist functionaries. Me, I’ve had enough of Marx.”

Hardly the words you’d expect from the man Peterson credits with figuring out “how to resurrect Marxism under a new guise”.

Foucault’s relationship to Marxism is not unlike Peterson’s own socialism. In the preface to his epic neo-Jungian work Maps of Meaning, he talks about his own membership of a socialist party when he first went to university.

“In the meantime, however, my nascent concern with questions of moral justice found immediate resolution. I started working as a volunteer for a mildly socialist political party, and adopted the party line. […]

Economic injustice was at the root of all evil, as far as I was concerned. Such injustice could be rectified, as a consequence of the rearrangement of social organizations. I could play a part in that admirable revolution, carrying out my ideological beliefs. Doubt vanished; my role was clear. Looking back, I am amazed at how stereotypical my actions—reactions—really were. I could not rationally accept the premises of religion as I understood them. I turned, in consequence, to dreams of political utopia, and personal power. The same ideological trap caught millions of others, in recent centuries.”

—Maps of Meaning, Preface

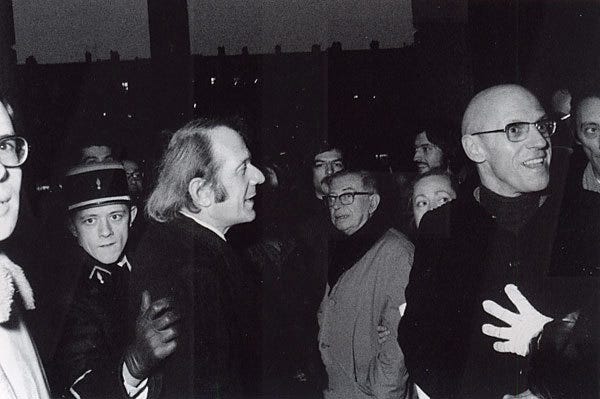

Michel Foucault: the Shadow of Jordan Peterson

The Jungian Shadow is the parts of ourselves that we hide in darkness — the parts that we repress. In his A Little Book on the Human Shadow, Robert Bly calls it “the long bag we drag behind us”. This Shadow is always with us. If we are not aware enough of it, it bleeds out.

Jung calls it the archetype of projection and this is the way in which we come to know our Shadow. We know it by how we react to others and to the world around us. A certain imbalance between the external stimulus and our reaction suggests the workings of the Shadow archetype.

With that in mind let’s talk about Michel Foucault let’s listen to the way Peterson characterises the French philosopher:

“Foucault in particular who never fit in anywhere who was an outcast in many ways and a bitter one and a suicidal one his entire life did everything he possibly could with his staggering IQ to figure out every treacherous way possible to undermine the structure that wouldn’t accept him in all his peculiarity. And it’s not wonder because there’s no way of making a structure that could possibly function if it was composed of people as peculiar bitter and resentful as Michel Foucault.”

As a big Jordan Peterson fan, this profile is a little haunting. It sounds uncomfortably close to how Peterson is portrayed by the people who despise him.

The unempathetic comments about the outcast with the poor mental health brings to mind the reactions on Twitter to Peterson’s journey through his hell of getting over benzos. The comments about IQ and the misfit whose voice was charged with bitterness and resentment — this sounds like a portrayal of Peterson himself by his opponents. And that is no coincidence.

In his work Psychology and Religion Carl Jung writes the following about the projection of the Shadow:

“Modern science has subtilized its projections to an almost unrecognizable degree, but our ordinary life still swarms with them. You can find them spread out in the newspapers, in books, rumours, and ordinary social gossip. All gaps in our actual knowledge are still filled out with projections. We are still so sure we know what other people think or what their true character is. We are convinced that certain people have all the bad qualities we do not know in ourselves or that they practise all those vices which could, of course, never be our own. We must still be exceedingly careful not to project our own shadows too shamelessly; we are still swamped with projected illusions.”

Seen through a Jungian lens then, Peterson’s rebellion against Derrida and Foucault is Peterson shadow boxing with his own repressed side. Peterson abandoned the path of social change in favour of personal transformation and personal responsibility. He abandoned the possibility of transformation in one quadrant and focused his belief on another.

The light of this focus on personal transformation and the depth of his knowledge casts a dark shadow however and we see this manifesting in his blind disdain for the Postmodernists.

But isn’t he right?

But you might rejoinder, isn’t he right? Don’t the Postmodernists talk about power? Weren’t they all Marxists?

Foucault does indeed talk about power. But rather than being Peterson’s Hobbesian boogeyman of groups fighting tooth and nail to the death, however, Foucault’s conception of power is very far from Hobbesian.

And in fact you would expect Peterson to have recognised Foucault’s use because it comes from the two men’s shared favourite philosopher: Friedrich Nietzsche.

Nietzsche was a much more substantial influence on Foucault than Marx ever was. Foucault’s conception of power is derived from Nietzsche’s Will to Power. Power in this sense isn’t a Hobbesian battleground but a neutral force. Power is the ocean we swim in. Foucault didn’t want to abolish power anymore than he wanted to abolish oxygen.

As Kévin Boucaud-Victoire and Daniel Zamora observed in an interview for Jacobin Magazine about Foucault’s experimentation with Neoliberalism:

“Boucaud-Victoire: Foucault did not believe in revolution, but rather in day-to-day micro-resistances, and in the need to “invent one’s own life.” He thought “one’s relation to oneself” was the “first and ultimate” point of “resistance to political power.”

Zamora: It was, I think, only in his last decade, through his interest in techniques of the self, that he started to grant the subject more autonomy. Thus, power gradually started to take shape as a blend of the techniques of constraint and techniques of the self, in which the subject constitutes itself. Power and resistance are now two sides of the same coin. The relation to the self thus becomes a potential space of freedom and autonomy that individuals can mobilize in opposition to power. […] Since power is omnipresent, Foucault’s thought didn’t aspire to “liberate” the individual, but rather to increase his autonomy.”

Using techniques of the self to garner more autonomy for the individual and to rebel against the tyrannical political power in society — gee who does that remind you of?

This isn’t exactly the Hobbesian battleground that Peterson was so afraid of. It’s not his nightmare of “the exercise of arbitrary power”. This is his own exact form of rebellion. This is another Nietzschean lover talking about using power in a Nietzschean sense to attain the autonomy of the individual against a structure of power.

In one of the greatest ironies in the history of ideas, Peterson’s main targets actually have the potential to be his greatest allies if only he could pierce through the fog of his own Shadow for long enough to do so.

Foucault was against the tyrannical uses of power and concerned himself greatly with the struggle against it. This sounds like a playbook Peterson could have learned a lot from.

Instead we get an intense Shadow projection. In a rather ironic twist, Peterson ends up making satanically possessed demons out of the two philosophers in the French tradition who are most heavily influenced by his own philosopher of choice Friedrich Nietzsche.

This Shadow doesn’t just end with a demonisation of Foucault and Derrida’s personality but extends much deeper.

The Neomarxist Conspiracy

In the psychological field that studies conspiracy theories, a conspiracy theory is defined as

“Explanations for important events that involve secret plots by powerful and malevolent groups” (Goertzel, 1994)

Peterson sees in the movements of these Postmodern Neo-Marxist philosophers a conspiracy to destroy the West.

Peterson argues that the Postmodernists managed to transform Marxism and with this transformed Marxism these Neo-Marxists planned to succeed where other revolutions had failed: they are going to take over and destroy Western culture from the inside. They have infiltrated the universities in a classic Trojan Horse.

For Peterson this represents the greatest threat to Western society

“I mean this intellectual war that’s going on in the universities is way deeper than a political war and way more way more serious than a political war. It manifests itself politically but, no, politics is way up the scale from where this is actually taking place”

Of course this picture is a little too perfect.

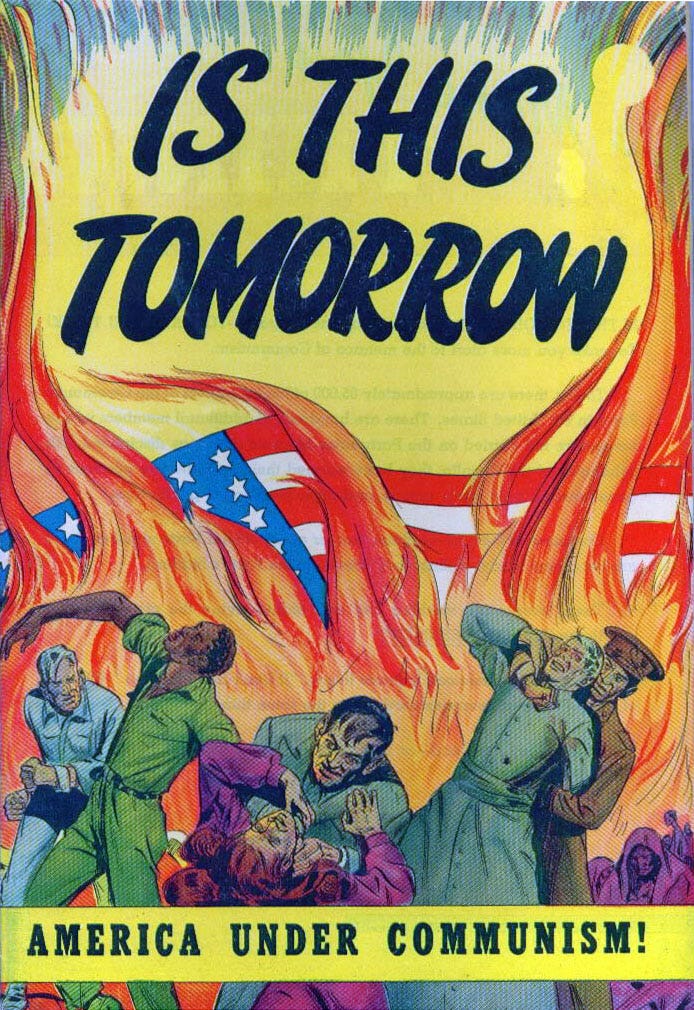

That’s something that should raise our suspicions. When the Nazis came to power, the people of Europe were already used to seeing Jewish people as the enemy.

In the North American psyche we have the exact same relationship with Communism. If you want to get Americans riled up about some nefarious takeover plot, there’s no better scapegoat than the good ol’ Commies.

And it’s not simply a question of Communism. The target of the Postmodern Neo-Marxists is nothing less than our Western values as a whole:

“post-modernism is a complete assault on […] everything that’s been established since the Enlightenment rationality empiricism science everything clarity of mind dialogue the idea of the individual all of that is is not only you see it’s not only that it’s up for grabs that’s not the thing it’s to be destroyed that’s the goal to be destroyed just like the Communists wanted you know wanted the revolution to destroy the capitalist system it’s the same thing”

So what we have here is a malevolent plot to deconstruct our Western society. Everything we hold dear is under threat and by who? None other than America’s great Cold War enemies — the Communists.

This is a conspiracy theory. And more than that it is a direct gaze into the Shadow of Jordan Peterson and the Shadow of our modern western culture.

We are possessed. Everyone has some jacked-up opinion on the culture wars. People are filled with fury. The fury is imbalanced. One might argue that this is down to the outrage fetishism of the algorithms but I would argue that these algorithms are in fact virtual bellows amplifying our culture’s archetypal Shadows.

Our culture has become an archetypal battleground. This is very far from a one-sided affair. Peterson is reacting to a Shadow on the other side and they are reacting to his. There’s something happening in the world but we have to be very careful here about getting involved in the realm of the gods. We are being possessed and thinking of ourselves as soldiers on some battlefield of the divinities.

This is what runs so counter to Peterson’s true message and a message I strongly believe in: make your bed, brush your teeth — as Voltaire would put it: cultivate your own garden.

You are human. You are one person surrounded by other people. Forget about this war between Aries and Artemis and focus on what it is to be human. Love your neighbour love yourself. It’s a lot simpler.

This stuff is intoxicating. It’s an 80% absinthe that everyone in the culture is drinking day in day out. If you find yourself getting really worked up and angry and thinking that other people are possessed by the devil, that you are a white knight going to save the world, you have gone beyond your proper bounds.

Jordan’s haters think that he is a lost cause but I this is very far from being the case. In his interview with John Vervaeke we see Peterson genuinely open to being corrected. He respects Vervaeke and knows that he operates in good faith and that his knowledge is superior in this domain and so Peterson genuinely asks Vervaeke showing that he is not so certain and that he is willing to learn.

While we might desire a bit more caution in the public sphere and suggest that perhaps we could do with more pause before rushing into an archetypal war over a lack of knowledge, nevertheless I think that Peterson is open to learning and he is a man who knows enough about the Shadow that he could even take this kind of criticism on board. My only fear is that as far as JP is concerned, it’s already too late.

I will leave you with a quote of Carl Jung’s from his book Psychology and Religion:

“The change of character brought about by the uprush of collective forces is amazing. A gentle and reasonable being can be transformed into a maniac or a savage beast. One is always inclined to lay the blame on external circumstances, but nothing could explode in us if it had not been there. As a matter of fact, we are constantly living on the edge of a volcano, and there is, so far as we know, no way of protecting ourselves from a possible outburst that will destroy everybody within reach. It is certainly a good thing to preach reason and common sense, but what if you have a lunatic asylum for an audience or a crowd in a collective frenzy? There is not much difference between them because the madman and the mob are both moved by impersonal, overwhelming forces.”

— Carl Jung, Psychology and Religion (1938)

4 Comments

Leave A Comment

It is impossible not to be stirred by the vehement passion of Peterson when talking about the Postmodern Neo-Marxists. Whether the feeling stirred is total rage at Peterson or at the so-called Social Justice Warriors depends of course on your own political leanings.

For those of us who are partial to a Jungian brew, this should have immediately stirred our suspicions. Because now looking back at it, it seems patently obvious that what we are seeing is a dance of the archetypal Shadow. Peterson’s narrative about the Postmodern Neo-Marxists goes, as we will see, beyond all reasonable bounds into the realm of conspiracy theory. It is not simple dismay with a cultural trend, it is the belief that this is a nefarious plot to overwhelm everything we hold dear.

When you put it like that it’s hard not to see Peterson’s Shadow. It’s written everywhere in this discourse. It makes a strawman out of its opponents and makes the French Continental philosophers into scapegoats for the decline of the West.

And what’s so perfect about it, is that Peterson’s discourse constellates the Shadow of the so-called Social Justice Warriors. They see an old privileged white man dismissing their oppression and calling them ungrateful for not loving the world they live in.

Carl Jung would have had a field day.

In an age ruled by controversy-loving algorithms Peterson’s Postmodern Neo-Marxist discourse was like catnip cut with crack cocaine. And it’s about time we pierced the veil.

In this edition then we are going to explore how Postmodern Neo-Marxism is a manifestation of Jordan Peterson’s Jungian Shadow and more specifically how Michel Foucault represents his bête noir.

To do this we’re first going to briefly reconstruct Peterson’s argument which comprises three main pieces:

1. The relativism of Postmodernism,

2. The Neo-Marxist “sleight of hand” and

3. The attack on Enlightenment values.

Once we’ve done that we will look at how Peterson’s argument is a manifestation of his Shadow in the form of an elaborate conspiracy theory that invokes the American psyche’s worst nightmares: Communism and an attack on the Enlightenment values of its Founding Fathers.

We are also going to look at why Peterson’s Shadow has been so explosive firstly because it is a collective shadow of one group in society and secondly because it powerfully constellates the complementary Shadow of the so-called Social Justice Warriors. In short it is a cocktail of Shadow psychology jacked up on algorithm juice and fuelled by mob mentality.

Peterson’s Argument

I first came across Jordan Peterson on Joe Rogan’s podcast a few months after his first appearance and I fell in love with him immediately. As a diehard lover of Nietzsche and Jung, Peterson’s lectures are nothing short of intellectual porn for me.

The only aspect of his work that I’m not keen on however happens to be the reason I and so many others discovered him. While I am sympathetic to many of Peterson’s points in the context of the “Culture Wars”, his main argument is built on what can only be described as a conspiracy theory.

As fans of JP, we have heard the Postmodern Neo-Marxist spiel a hundred times before but I’m going to try here to reconstruct the key points of his overall argument so that we all know what we’re talking about.

For Peterson there are three critical aspects to the Postmodern Neo-Marxist framework: there’s the Postmodernist element, the Neo-Marxist element and their target: Western society’s Enlightenment values.

1. The Postmodernist strain

The first part then is the Postmodernist element. Later on we’re going to touch briefly on the slipperiness of the term Postmodernist but for now we’ll take it for granted and focus on Peterson’s characterisation of this movement which for all intents and purposes is made up of Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault in Peterson’s eyes.

Other than one passing reference to Lyotard, another to Sartre and a few to Lacan, Peterson never really discusses any other philosophers of this era in any depth. His targets are Derrida and Foucault.

Peterson identifies one doctrine above all with this tradition and that is relativism.

JP usually frames this in terms of Derrida’s “there is nothing outside the text” basically the idea that when reading any text there are an infinite number of interpretations that can be brought to bear on it. But that is not all — none of these interpretations can be privileged above the others.

And this is just the beginning because the world is infinitely more complex than any individual text and so any interpretation we make of the world is only going to be one interpretation among many. There is no canonical interpretation — no final and ultimate truth.

This relativism is the first aspect of Peterson’s Postmodern Neo-Marxist equation. The second element is the Neo-Marxist piece.

2. The Neo-Marxist strain

Peterson argues that in the 1960s and 70s, the Postmodern philosophers pulled off what he repeatedly calls a “sleight of hand”.

The argument goes something like this: French philosophy in the mid-20th century was riddled with Marxism. But in the 1960s and 70s, as the horrors of the Gulags and of Mao’s Cultural Revolution began to emerge, Communism became an untenable position.

So with Communism now untenable, the French philosophers who were so fond of Karl Marx were presented with a major problem: what to do about Marxism?

And so they found a solution: they performed a sleight of hand that allowed them to not only keep their Marxist philosophy but in doing so devise an even more nefarious plan where they, like any good villain, try to take over the world.

They swapped out Marxism’s narrative of history being a neverending class struggle between the bourgeoise and the proletariat, and replaced it with a slightly more abstracted version.

The Postmodernists parted with Marxism’s economic version of the oppressor/oppressed and replaced it with a group identity-based model of oppressor/oppressed.

And with that done, the French philosophy ostensibly left behind Marxism and instead fomented a different type of revolution. Classical Marxism had been reborn as Identity Politics. But that’s not all.

This is where the argument — if it hadn’t already — enters the unambiguous waters of conspiracy theory. Peterson seems to argue that these Postmodern Neo-Marxists were not merely teaching their beliefs but that there some sort of method to it all.

Instead of the Marxists taking over the world through a violent revolution, the Neo-Marxist or “Cultural Marxists” take over society by capturing the education system. This isn’t an accident but a plot.

3. The attack on Enlightenment values

And that brings us onto the third element of Peterson’s argument: the target of the Postmodern Neo-Marxists. And true to form, these pesky Postmodern Neo-Marxists target the same thing all Shadow villains go after: everything we hold dear.

The Postmodern Neo-Marxists want to deconstruct everything established since the Enlightenment — rationality, empiricism, science, clarity of mind, dialogue, the idea of the individual. Just as Communism wanted to destroy the capitalist system, the Postmodern Neo-Marxists want to dismantle the Enlightenment values of the West.

Counterargument

We have our bete noire and say with the old Pharisee: “God, I thank thee, that I am not as other men are.”

We don’t want to know that we are the “other men.”

— Carl Jung, ETH Lecture 27 Jan 1939

There are many weak points to Peterson’s argument. First off it should be pointed out that Peterson imbibed most of this theory — seemingly unquestioningly — from the poorly referenced work of Stephen Hicks. For a breakdown of the many many scholarly errors in Hicks’s book I’d highly recommend Jonas Ceika’s video dissection.

While my focus is predominantly on the psychology of Peterson, I think it is worth mentioning a couple of broader points beforehand.

Firstly the term postmodernist is not nearly as uncontroversial as it seems. It’s worth remembering that Postmodernism isn’t a term that these philosophers applied to themselves.

And so it is a slippery term that we must be careful with. These philosophers don’t fall into such a natural grouping together that we can talk about their views as a homogenous whole.

When Peterson talks about the focus of Postmodernism being a scepticism of grand narratives you have to remember this was Lyotard’s characterisation of Postmodernity and not a manifesto written by a group of philosophers who called themselves Postmodernists.

Secondly the collapse of Marxism is not nearly as dramatic as Peterson makes it out to be. It was very far from becoming a taboo position.

Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago — which Peterson identifies as the catalyst for the downfall of Communism — was published in 1974. In the next election in 1978 the French Communist party received its highest number of votes ever. In total they got 5.8 million votes up from 5 million in 1973. That’s more than 20% of the French public voting for the Communist party. And while Communism’s star was waning, the Communist candidate for the 1981 French Presidency still received 4.4 million votes. That’s very far from being an untenable position.

A third point worth noting is Peterson’s characterisation of Derrida and Foucault as being fervent Marxists. Anyone who has studied either thinker knows this to be patently false.

Derrida is perhaps the least political of all the so-called Postmodernist philosophers. He finally broke his silence with 1993’s Spectres of Marx but this is much more a dismissal of Marxism and a transcendence of it than anything else.

Foucault on the other hand was the French philosopher most known for savaging Marx and Marxists. He became a member of the Communist Party for a year when he first entered university but unlike his classmates he left disgusted with Marxism. This was in the 1940s, long before anything about the Gulags or about Mao. In 1975, when Foucault was protesting the impending execution of 11 Spaniards without trial by the Fascist regime of General Franco, a young militant asked Foucault if he would give a talk to his group about Marx. Foucault snapped at him:

“Don’t talk to me about Marx any more! I never want to hear anything about that man again. Ask someone whose job it is. Someone paid to do it. Ask the Marxist functionaries. Me, I’ve had enough of Marx.”

Hardly the words you’d expect from the man Peterson credits with figuring out “how to resurrect Marxism under a new guise”.

Foucault’s relationship to Marxism is not unlike Peterson’s own socialism. In the preface to his epic neo-Jungian work Maps of Meaning, he talks about his own membership of a socialist party when he first went to university.

“In the meantime, however, my nascent concern with questions of moral justice found immediate resolution. I started working as a volunteer for a mildly socialist political party, and adopted the party line. […]

Economic injustice was at the root of all evil, as far as I was concerned. Such injustice could be rectified, as a consequence of the rearrangement of social organizations. I could play a part in that admirable revolution, carrying out my ideological beliefs. Doubt vanished; my role was clear. Looking back, I am amazed at how stereotypical my actions—reactions—really were. I could not rationally accept the premises of religion as I understood them. I turned, in consequence, to dreams of political utopia, and personal power. The same ideological trap caught millions of others, in recent centuries.”

—Maps of Meaning, Preface

Michel Foucault: the Shadow of Jordan Peterson

The Jungian Shadow is the parts of ourselves that we hide in darkness — the parts that we repress. In his A Little Book on the Human Shadow, Robert Bly calls it “the long bag we drag behind us”. This Shadow is always with us. If we are not aware enough of it, it bleeds out.

Jung calls it the archetype of projection and this is the way in which we come to know our Shadow. We know it by how we react to others and to the world around us. A certain imbalance between the external stimulus and our reaction suggests the workings of the Shadow archetype.

With that in mind let’s talk about Michel Foucault let’s listen to the way Peterson characterises the French philosopher:

“Foucault in particular who never fit in anywhere who was an outcast in many ways and a bitter one and a suicidal one his entire life did everything he possibly could with his staggering IQ to figure out every treacherous way possible to undermine the structure that wouldn’t accept him in all his peculiarity. And it’s not wonder because there’s no way of making a structure that could possibly function if it was composed of people as peculiar bitter and resentful as Michel Foucault.”

As a big Jordan Peterson fan, this profile is a little haunting. It sounds uncomfortably close to how Peterson is portrayed by the people who despise him.

The unempathetic comments about the outcast with the poor mental health brings to mind the reactions on Twitter to Peterson’s journey through his hell of getting over benzos. The comments about IQ and the misfit whose voice was charged with bitterness and resentment — this sounds like a portrayal of Peterson himself by his opponents. And that is no coincidence.

In his work Psychology and Religion Carl Jung writes the following about the projection of the Shadow:

“Modern science has subtilized its projections to an almost unrecognizable degree, but our ordinary life still swarms with them. You can find them spread out in the newspapers, in books, rumours, and ordinary social gossip. All gaps in our actual knowledge are still filled out with projections. We are still so sure we know what other people think or what their true character is. We are convinced that certain people have all the bad qualities we do not know in ourselves or that they practise all those vices which could, of course, never be our own. We must still be exceedingly careful not to project our own shadows too shamelessly; we are still swamped with projected illusions.”

Seen through a Jungian lens then, Peterson’s rebellion against Derrida and Foucault is Peterson shadow boxing with his own repressed side. Peterson abandoned the path of social change in favour of personal transformation and personal responsibility. He abandoned the possibility of transformation in one quadrant and focused his belief on another.

The light of this focus on personal transformation and the depth of his knowledge casts a dark shadow however and we see this manifesting in his blind disdain for the Postmodernists.

But isn’t he right?

But you might rejoinder, isn’t he right? Don’t the Postmodernists talk about power? Weren’t they all Marxists?

Foucault does indeed talk about power. But rather than being Peterson’s Hobbesian boogeyman of groups fighting tooth and nail to the death, however, Foucault’s conception of power is very far from Hobbesian.

And in fact you would expect Peterson to have recognised Foucault’s use because it comes from the two men’s shared favourite philosopher: Friedrich Nietzsche.

Nietzsche was a much more substantial influence on Foucault than Marx ever was. Foucault’s conception of power is derived from Nietzsche’s Will to Power. Power in this sense isn’t a Hobbesian battleground but a neutral force. Power is the ocean we swim in. Foucault didn’t want to abolish power anymore than he wanted to abolish oxygen.

As Kévin Boucaud-Victoire and Daniel Zamora observed in an interview for Jacobin Magazine about Foucault’s experimentation with Neoliberalism:

“Boucaud-Victoire: Foucault did not believe in revolution, but rather in day-to-day micro-resistances, and in the need to “invent one’s own life.” He thought “one’s relation to oneself” was the “first and ultimate” point of “resistance to political power.”

Zamora: It was, I think, only in his last decade, through his interest in techniques of the self, that he started to grant the subject more autonomy. Thus, power gradually started to take shape as a blend of the techniques of constraint and techniques of the self, in which the subject constitutes itself. Power and resistance are now two sides of the same coin. The relation to the self thus becomes a potential space of freedom and autonomy that individuals can mobilize in opposition to power. […] Since power is omnipresent, Foucault’s thought didn’t aspire to “liberate” the individual, but rather to increase his autonomy.”

Using techniques of the self to garner more autonomy for the individual and to rebel against the tyrannical political power in society — gee who does that remind you of?

This isn’t exactly the Hobbesian battleground that Peterson was so afraid of. It’s not his nightmare of “the exercise of arbitrary power”. This is his own exact form of rebellion. This is another Nietzschean lover talking about using power in a Nietzschean sense to attain the autonomy of the individual against a structure of power.

In one of the greatest ironies in the history of ideas, Peterson’s main targets actually have the potential to be his greatest allies if only he could pierce through the fog of his own Shadow for long enough to do so.

Foucault was against the tyrannical uses of power and concerned himself greatly with the struggle against it. This sounds like a playbook Peterson could have learned a lot from.

Instead we get an intense Shadow projection. In a rather ironic twist, Peterson ends up making satanically possessed demons out of the two philosophers in the French tradition who are most heavily influenced by his own philosopher of choice Friedrich Nietzsche.

This Shadow doesn’t just end with a demonisation of Foucault and Derrida’s personality but extends much deeper.

The Neomarxist Conspiracy

In the psychological field that studies conspiracy theories, a conspiracy theory is defined as

“Explanations for important events that involve secret plots by powerful and malevolent groups” (Goertzel, 1994)

Peterson sees in the movements of these Postmodern Neo-Marxist philosophers a conspiracy to destroy the West.

Peterson argues that the Postmodernists managed to transform Marxism and with this transformed Marxism these Neo-Marxists planned to succeed where other revolutions had failed: they are going to take over and destroy Western culture from the inside. They have infiltrated the universities in a classic Trojan Horse.

For Peterson this represents the greatest threat to Western society

“I mean this intellectual war that’s going on in the universities is way deeper than a political war and way more way more serious than a political war. It manifests itself politically but, no, politics is way up the scale from where this is actually taking place”

Of course this picture is a little too perfect.

That’s something that should raise our suspicions. When the Nazis came to power, the people of Europe were already used to seeing Jewish people as the enemy.

In the North American psyche we have the exact same relationship with Communism. If you want to get Americans riled up about some nefarious takeover plot, there’s no better scapegoat than the good ol’ Commies.

And it’s not simply a question of Communism. The target of the Postmodern Neo-Marxists is nothing less than our Western values as a whole:

“post-modernism is a complete assault on […] everything that’s been established since the Enlightenment rationality empiricism science everything clarity of mind dialogue the idea of the individual all of that is is not only you see it’s not only that it’s up for grabs that’s not the thing it’s to be destroyed that’s the goal to be destroyed just like the Communists wanted you know wanted the revolution to destroy the capitalist system it’s the same thing”

So what we have here is a malevolent plot to deconstruct our Western society. Everything we hold dear is under threat and by who? None other than America’s great Cold War enemies — the Communists.

This is a conspiracy theory. And more than that it is a direct gaze into the Shadow of Jordan Peterson and the Shadow of our modern western culture.

We are possessed. Everyone has some jacked-up opinion on the culture wars. People are filled with fury. The fury is imbalanced. One might argue that this is down to the outrage fetishism of the algorithms but I would argue that these algorithms are in fact virtual bellows amplifying our culture’s archetypal Shadows.

Our culture has become an archetypal battleground. This is very far from a one-sided affair. Peterson is reacting to a Shadow on the other side and they are reacting to his. There’s something happening in the world but we have to be very careful here about getting involved in the realm of the gods. We are being possessed and thinking of ourselves as soldiers on some battlefield of the divinities.

This is what runs so counter to Peterson’s true message and a message I strongly believe in: make your bed, brush your teeth — as Voltaire would put it: cultivate your own garden.

You are human. You are one person surrounded by other people. Forget about this war between Aries and Artemis and focus on what it is to be human. Love your neighbour love yourself. It’s a lot simpler.

This stuff is intoxicating. It’s an 80% absinthe that everyone in the culture is drinking day in day out. If you find yourself getting really worked up and angry and thinking that other people are possessed by the devil, that you are a white knight going to save the world, you have gone beyond your proper bounds.

Jordan’s haters think that he is a lost cause but I this is very far from being the case. In his interview with John Vervaeke we see Peterson genuinely open to being corrected. He respects Vervaeke and knows that he operates in good faith and that his knowledge is superior in this domain and so Peterson genuinely asks Vervaeke showing that he is not so certain and that he is willing to learn.

While we might desire a bit more caution in the public sphere and suggest that perhaps we could do with more pause before rushing into an archetypal war over a lack of knowledge, nevertheless I think that Peterson is open to learning and he is a man who knows enough about the Shadow that he could even take this kind of criticism on board. My only fear is that as far as JP is concerned, it’s already too late.

I will leave you with a quote of Carl Jung’s from his book Psychology and Religion:

“The change of character brought about by the uprush of collective forces is amazing. A gentle and reasonable being can be transformed into a maniac or a savage beast. One is always inclined to lay the blame on external circumstances, but nothing could explode in us if it had not been there. As a matter of fact, we are constantly living on the edge of a volcano, and there is, so far as we know, no way of protecting ourselves from a possible outburst that will destroy everybody within reach. It is certainly a good thing to preach reason and common sense, but what if you have a lunatic asylum for an audience or a crowd in a collective frenzy? There is not much difference between them because the madman and the mob are both moved by impersonal, overwhelming forces.”

— Carl Jung, Psychology and Religion (1938)

4 Comments

-

[…] we’ve been exploring about recently on the channel it’s a way of understanding the voice of Jordan Peterson in contrast to that of Michel Foucault and the social justice movement. It’s also a good way of situating a lot of the material we have […]

-

[…] exploration goes back far beyond Jordan Peterson’s Postmodern Neo-Marxists back even beyond Marx himself to the age of the Enlightenment and looks at the evolution of these […]

-

[…] psychologist Peterson (in stark contrast to the culture warrior Peterson) encourages people to become responsible. He encourages them to take steps to improve their life […]

-

[…] is the ocean of chaos that renews the Order of Structure. As Jordan Peterson explores in his book Maps of Meaning an order that goes too long without being resubmerged in the […]

Leave A Comment

It is impossible not to be stirred by the vehement passion of Peterson when talking about the Postmodern Neo-Marxists. Whether the feeling stirred is total rage at Peterson or at the so-called Social Justice Warriors depends of course on your own political leanings.

For those of us who are partial to a Jungian brew, this should have immediately stirred our suspicions. Because now looking back at it, it seems patently obvious that what we are seeing is a dance of the archetypal Shadow. Peterson’s narrative about the Postmodern Neo-Marxists goes, as we will see, beyond all reasonable bounds into the realm of conspiracy theory. It is not simple dismay with a cultural trend, it is the belief that this is a nefarious plot to overwhelm everything we hold dear.

When you put it like that it’s hard not to see Peterson’s Shadow. It’s written everywhere in this discourse. It makes a strawman out of its opponents and makes the French Continental philosophers into scapegoats for the decline of the West.

And what’s so perfect about it, is that Peterson’s discourse constellates the Shadow of the so-called Social Justice Warriors. They see an old privileged white man dismissing their oppression and calling them ungrateful for not loving the world they live in.

Carl Jung would have had a field day.

In an age ruled by controversy-loving algorithms Peterson’s Postmodern Neo-Marxist discourse was like catnip cut with crack cocaine. And it’s about time we pierced the veil.

In this edition then we are going to explore how Postmodern Neo-Marxism is a manifestation of Jordan Peterson’s Jungian Shadow and more specifically how Michel Foucault represents his bête noir.

To do this we’re first going to briefly reconstruct Peterson’s argument which comprises three main pieces:

1. The relativism of Postmodernism,

2. The Neo-Marxist “sleight of hand” and

3. The attack on Enlightenment values.

Once we’ve done that we will look at how Peterson’s argument is a manifestation of his Shadow in the form of an elaborate conspiracy theory that invokes the American psyche’s worst nightmares: Communism and an attack on the Enlightenment values of its Founding Fathers.

We are also going to look at why Peterson’s Shadow has been so explosive firstly because it is a collective shadow of one group in society and secondly because it powerfully constellates the complementary Shadow of the so-called Social Justice Warriors. In short it is a cocktail of Shadow psychology jacked up on algorithm juice and fuelled by mob mentality.

Peterson’s Argument

I first came across Jordan Peterson on Joe Rogan’s podcast a few months after his first appearance and I fell in love with him immediately. As a diehard lover of Nietzsche and Jung, Peterson’s lectures are nothing short of intellectual porn for me.

The only aspect of his work that I’m not keen on however happens to be the reason I and so many others discovered him. While I am sympathetic to many of Peterson’s points in the context of the “Culture Wars”, his main argument is built on what can only be described as a conspiracy theory.

As fans of JP, we have heard the Postmodern Neo-Marxist spiel a hundred times before but I’m going to try here to reconstruct the key points of his overall argument so that we all know what we’re talking about.

For Peterson there are three critical aspects to the Postmodern Neo-Marxist framework: there’s the Postmodernist element, the Neo-Marxist element and their target: Western society’s Enlightenment values.

1. The Postmodernist strain

The first part then is the Postmodernist element. Later on we’re going to touch briefly on the slipperiness of the term Postmodernist but for now we’ll take it for granted and focus on Peterson’s characterisation of this movement which for all intents and purposes is made up of Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault in Peterson’s eyes.

Other than one passing reference to Lyotard, another to Sartre and a few to Lacan, Peterson never really discusses any other philosophers of this era in any depth. His targets are Derrida and Foucault.

Peterson identifies one doctrine above all with this tradition and that is relativism.

JP usually frames this in terms of Derrida’s “there is nothing outside the text” basically the idea that when reading any text there are an infinite number of interpretations that can be brought to bear on it. But that is not all — none of these interpretations can be privileged above the others.

And this is just the beginning because the world is infinitely more complex than any individual text and so any interpretation we make of the world is only going to be one interpretation among many. There is no canonical interpretation — no final and ultimate truth.

This relativism is the first aspect of Peterson’s Postmodern Neo-Marxist equation. The second element is the Neo-Marxist piece.

2. The Neo-Marxist strain

Peterson argues that in the 1960s and 70s, the Postmodern philosophers pulled off what he repeatedly calls a “sleight of hand”.

The argument goes something like this: French philosophy in the mid-20th century was riddled with Marxism. But in the 1960s and 70s, as the horrors of the Gulags and of Mao’s Cultural Revolution began to emerge, Communism became an untenable position.

So with Communism now untenable, the French philosophers who were so fond of Karl Marx were presented with a major problem: what to do about Marxism?

And so they found a solution: they performed a sleight of hand that allowed them to not only keep their Marxist philosophy but in doing so devise an even more nefarious plan where they, like any good villain, try to take over the world.

They swapped out Marxism’s narrative of history being a neverending class struggle between the bourgeoise and the proletariat, and replaced it with a slightly more abstracted version.

The Postmodernists parted with Marxism’s economic version of the oppressor/oppressed and replaced it with a group identity-based model of oppressor/oppressed.

And with that done, the French philosophy ostensibly left behind Marxism and instead fomented a different type of revolution. Classical Marxism had been reborn as Identity Politics. But that’s not all.

This is where the argument — if it hadn’t already — enters the unambiguous waters of conspiracy theory. Peterson seems to argue that these Postmodern Neo-Marxists were not merely teaching their beliefs but that there some sort of method to it all.

Instead of the Marxists taking over the world through a violent revolution, the Neo-Marxist or “Cultural Marxists” take over society by capturing the education system. This isn’t an accident but a plot.

3. The attack on Enlightenment values

And that brings us onto the third element of Peterson’s argument: the target of the Postmodern Neo-Marxists. And true to form, these pesky Postmodern Neo-Marxists target the same thing all Shadow villains go after: everything we hold dear.

The Postmodern Neo-Marxists want to deconstruct everything established since the Enlightenment — rationality, empiricism, science, clarity of mind, dialogue, the idea of the individual. Just as Communism wanted to destroy the capitalist system, the Postmodern Neo-Marxists want to dismantle the Enlightenment values of the West.

Counterargument

We have our bete noire and say with the old Pharisee: “God, I thank thee, that I am not as other men are.”

We don’t want to know that we are the “other men.”

— Carl Jung, ETH Lecture 27 Jan 1939

There are many weak points to Peterson’s argument. First off it should be pointed out that Peterson imbibed most of this theory — seemingly unquestioningly — from the poorly referenced work of Stephen Hicks. For a breakdown of the many many scholarly errors in Hicks’s book I’d highly recommend Jonas Ceika’s video dissection.

While my focus is predominantly on the psychology of Peterson, I think it is worth mentioning a couple of broader points beforehand.

Firstly the term postmodernist is not nearly as uncontroversial as it seems. It’s worth remembering that Postmodernism isn’t a term that these philosophers applied to themselves.

And so it is a slippery term that we must be careful with. These philosophers don’t fall into such a natural grouping together that we can talk about their views as a homogenous whole.

When Peterson talks about the focus of Postmodernism being a scepticism of grand narratives you have to remember this was Lyotard’s characterisation of Postmodernity and not a manifesto written by a group of philosophers who called themselves Postmodernists.

Secondly the collapse of Marxism is not nearly as dramatic as Peterson makes it out to be. It was very far from becoming a taboo position.

Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago — which Peterson identifies as the catalyst for the downfall of Communism — was published in 1974. In the next election in 1978 the French Communist party received its highest number of votes ever. In total they got 5.8 million votes up from 5 million in 1973. That’s more than 20% of the French public voting for the Communist party. And while Communism’s star was waning, the Communist candidate for the 1981 French Presidency still received 4.4 million votes. That’s very far from being an untenable position.

A third point worth noting is Peterson’s characterisation of Derrida and Foucault as being fervent Marxists. Anyone who has studied either thinker knows this to be patently false.

Derrida is perhaps the least political of all the so-called Postmodernist philosophers. He finally broke his silence with 1993’s Spectres of Marx but this is much more a dismissal of Marxism and a transcendence of it than anything else.

Foucault on the other hand was the French philosopher most known for savaging Marx and Marxists. He became a member of the Communist Party for a year when he first entered university but unlike his classmates he left disgusted with Marxism. This was in the 1940s, long before anything about the Gulags or about Mao. In 1975, when Foucault was protesting the impending execution of 11 Spaniards without trial by the Fascist regime of General Franco, a young militant asked Foucault if he would give a talk to his group about Marx. Foucault snapped at him:

“Don’t talk to me about Marx any more! I never want to hear anything about that man again. Ask someone whose job it is. Someone paid to do it. Ask the Marxist functionaries. Me, I’ve had enough of Marx.”

Hardly the words you’d expect from the man Peterson credits with figuring out “how to resurrect Marxism under a new guise”.

Foucault’s relationship to Marxism is not unlike Peterson’s own socialism. In the preface to his epic neo-Jungian work Maps of Meaning, he talks about his own membership of a socialist party when he first went to university.

“In the meantime, however, my nascent concern with questions of moral justice found immediate resolution. I started working as a volunteer for a mildly socialist political party, and adopted the party line. […]

Economic injustice was at the root of all evil, as far as I was concerned. Such injustice could be rectified, as a consequence of the rearrangement of social organizations. I could play a part in that admirable revolution, carrying out my ideological beliefs. Doubt vanished; my role was clear. Looking back, I am amazed at how stereotypical my actions—reactions—really were. I could not rationally accept the premises of religion as I understood them. I turned, in consequence, to dreams of political utopia, and personal power. The same ideological trap caught millions of others, in recent centuries.”

—Maps of Meaning, Preface

Michel Foucault: the Shadow of Jordan Peterson

The Jungian Shadow is the parts of ourselves that we hide in darkness — the parts that we repress. In his A Little Book on the Human Shadow, Robert Bly calls it “the long bag we drag behind us”. This Shadow is always with us. If we are not aware enough of it, it bleeds out.

Jung calls it the archetype of projection and this is the way in which we come to know our Shadow. We know it by how we react to others and to the world around us. A certain imbalance between the external stimulus and our reaction suggests the workings of the Shadow archetype.

With that in mind let’s talk about Michel Foucault let’s listen to the way Peterson characterises the French philosopher:

“Foucault in particular who never fit in anywhere who was an outcast in many ways and a bitter one and a suicidal one his entire life did everything he possibly could with his staggering IQ to figure out every treacherous way possible to undermine the structure that wouldn’t accept him in all his peculiarity. And it’s not wonder because there’s no way of making a structure that could possibly function if it was composed of people as peculiar bitter and resentful as Michel Foucault.”

As a big Jordan Peterson fan, this profile is a little haunting. It sounds uncomfortably close to how Peterson is portrayed by the people who despise him.

The unempathetic comments about the outcast with the poor mental health brings to mind the reactions on Twitter to Peterson’s journey through his hell of getting over benzos. The comments about IQ and the misfit whose voice was charged with bitterness and resentment — this sounds like a portrayal of Peterson himself by his opponents. And that is no coincidence.

In his work Psychology and Religion Carl Jung writes the following about the projection of the Shadow:

“Modern science has subtilized its projections to an almost unrecognizable degree, but our ordinary life still swarms with them. You can find them spread out in the newspapers, in books, rumours, and ordinary social gossip. All gaps in our actual knowledge are still filled out with projections. We are still so sure we know what other people think or what their true character is. We are convinced that certain people have all the bad qualities we do not know in ourselves or that they practise all those vices which could, of course, never be our own. We must still be exceedingly careful not to project our own shadows too shamelessly; we are still swamped with projected illusions.”

Seen through a Jungian lens then, Peterson’s rebellion against Derrida and Foucault is Peterson shadow boxing with his own repressed side. Peterson abandoned the path of social change in favour of personal transformation and personal responsibility. He abandoned the possibility of transformation in one quadrant and focused his belief on another.

The light of this focus on personal transformation and the depth of his knowledge casts a dark shadow however and we see this manifesting in his blind disdain for the Postmodernists.

But isn’t he right?

But you might rejoinder, isn’t he right? Don’t the Postmodernists talk about power? Weren’t they all Marxists?

Foucault does indeed talk about power. But rather than being Peterson’s Hobbesian boogeyman of groups fighting tooth and nail to the death, however, Foucault’s conception of power is very far from Hobbesian.

And in fact you would expect Peterson to have recognised Foucault’s use because it comes from the two men’s shared favourite philosopher: Friedrich Nietzsche.

Nietzsche was a much more substantial influence on Foucault than Marx ever was. Foucault’s conception of power is derived from Nietzsche’s Will to Power. Power in this sense isn’t a Hobbesian battleground but a neutral force. Power is the ocean we swim in. Foucault didn’t want to abolish power anymore than he wanted to abolish oxygen.

As Kévin Boucaud-Victoire and Daniel Zamora observed in an interview for Jacobin Magazine about Foucault’s experimentation with Neoliberalism:

“Boucaud-Victoire: Foucault did not believe in revolution, but rather in day-to-day micro-resistances, and in the need to “invent one’s own life.” He thought “one’s relation to oneself” was the “first and ultimate” point of “resistance to political power.”

Zamora: It was, I think, only in his last decade, through his interest in techniques of the self, that he started to grant the subject more autonomy. Thus, power gradually started to take shape as a blend of the techniques of constraint and techniques of the self, in which the subject constitutes itself. Power and resistance are now two sides of the same coin. The relation to the self thus becomes a potential space of freedom and autonomy that individuals can mobilize in opposition to power. […] Since power is omnipresent, Foucault’s thought didn’t aspire to “liberate” the individual, but rather to increase his autonomy.”

Using techniques of the self to garner more autonomy for the individual and to rebel against the tyrannical political power in society — gee who does that remind you of?

This isn’t exactly the Hobbesian battleground that Peterson was so afraid of. It’s not his nightmare of “the exercise of arbitrary power”. This is his own exact form of rebellion. This is another Nietzschean lover talking about using power in a Nietzschean sense to attain the autonomy of the individual against a structure of power.

In one of the greatest ironies in the history of ideas, Peterson’s main targets actually have the potential to be his greatest allies if only he could pierce through the fog of his own Shadow for long enough to do so.

Foucault was against the tyrannical uses of power and concerned himself greatly with the struggle against it. This sounds like a playbook Peterson could have learned a lot from.

Instead we get an intense Shadow projection. In a rather ironic twist, Peterson ends up making satanically possessed demons out of the two philosophers in the French tradition who are most heavily influenced by his own philosopher of choice Friedrich Nietzsche.

This Shadow doesn’t just end with a demonisation of Foucault and Derrida’s personality but extends much deeper.

The Neomarxist Conspiracy

In the psychological field that studies conspiracy theories, a conspiracy theory is defined as

“Explanations for important events that involve secret plots by powerful and malevolent groups” (Goertzel, 1994)

Peterson sees in the movements of these Postmodern Neo-Marxist philosophers a conspiracy to destroy the West.

Peterson argues that the Postmodernists managed to transform Marxism and with this transformed Marxism these Neo-Marxists planned to succeed where other revolutions had failed: they are going to take over and destroy Western culture from the inside. They have infiltrated the universities in a classic Trojan Horse.

For Peterson this represents the greatest threat to Western society

“I mean this intellectual war that’s going on in the universities is way deeper than a political war and way more way more serious than a political war. It manifests itself politically but, no, politics is way up the scale from where this is actually taking place”

Of course this picture is a little too perfect.

That’s something that should raise our suspicions. When the Nazis came to power, the people of Europe were already used to seeing Jewish people as the enemy.

In the North American psyche we have the exact same relationship with Communism. If you want to get Americans riled up about some nefarious takeover plot, there’s no better scapegoat than the good ol’ Commies.

And it’s not simply a question of Communism. The target of the Postmodern Neo-Marxists is nothing less than our Western values as a whole:

“post-modernism is a complete assault on […] everything that’s been established since the Enlightenment rationality empiricism science everything clarity of mind dialogue the idea of the individual all of that is is not only you see it’s not only that it’s up for grabs that’s not the thing it’s to be destroyed that’s the goal to be destroyed just like the Communists wanted you know wanted the revolution to destroy the capitalist system it’s the same thing”

So what we have here is a malevolent plot to deconstruct our Western society. Everything we hold dear is under threat and by who? None other than America’s great Cold War enemies — the Communists.

This is a conspiracy theory. And more than that it is a direct gaze into the Shadow of Jordan Peterson and the Shadow of our modern western culture.

We are possessed. Everyone has some jacked-up opinion on the culture wars. People are filled with fury. The fury is imbalanced. One might argue that this is down to the outrage fetishism of the algorithms but I would argue that these algorithms are in fact virtual bellows amplifying our culture’s archetypal Shadows.

Our culture has become an archetypal battleground. This is very far from a one-sided affair. Peterson is reacting to a Shadow on the other side and they are reacting to his. There’s something happening in the world but we have to be very careful here about getting involved in the realm of the gods. We are being possessed and thinking of ourselves as soldiers on some battlefield of the divinities.

This is what runs so counter to Peterson’s true message and a message I strongly believe in: make your bed, brush your teeth — as Voltaire would put it: cultivate your own garden.

You are human. You are one person surrounded by other people. Forget about this war between Aries and Artemis and focus on what it is to be human. Love your neighbour love yourself. It’s a lot simpler.

This stuff is intoxicating. It’s an 80% absinthe that everyone in the culture is drinking day in day out. If you find yourself getting really worked up and angry and thinking that other people are possessed by the devil, that you are a white knight going to save the world, you have gone beyond your proper bounds.

Jordan’s haters think that he is a lost cause but I this is very far from being the case. In his interview with John Vervaeke we see Peterson genuinely open to being corrected. He respects Vervaeke and knows that he operates in good faith and that his knowledge is superior in this domain and so Peterson genuinely asks Vervaeke showing that he is not so certain and that he is willing to learn.

While we might desire a bit more caution in the public sphere and suggest that perhaps we could do with more pause before rushing into an archetypal war over a lack of knowledge, nevertheless I think that Peterson is open to learning and he is a man who knows enough about the Shadow that he could even take this kind of criticism on board. My only fear is that as far as JP is concerned, it’s already too late.

I will leave you with a quote of Carl Jung’s from his book Psychology and Religion:

“The change of character brought about by the uprush of collective forces is amazing. A gentle and reasonable being can be transformed into a maniac or a savage beast. One is always inclined to lay the blame on external circumstances, but nothing could explode in us if it had not been there. As a matter of fact, we are constantly living on the edge of a volcano, and there is, so far as we know, no way of protecting ourselves from a possible outburst that will destroy everybody within reach. It is certainly a good thing to preach reason and common sense, but what if you have a lunatic asylum for an audience or a crowd in a collective frenzy? There is not much difference between them because the madman and the mob are both moved by impersonal, overwhelming forces.”

— Carl Jung, Psychology and Religion (1938)

4 Comments

-

[…] we’ve been exploring about recently on the channel it’s a way of understanding the voice of Jordan Peterson in contrast to that of Michel Foucault and the social justice movement. It’s also a good way of situating a lot of the material we have […]

-

[…] exploration goes back far beyond Jordan Peterson’s Postmodern Neo-Marxists back even beyond Marx himself to the age of the Enlightenment and looks at the evolution of these […]

-

[…] psychologist Peterson (in stark contrast to the culture warrior Peterson) encourages people to become responsible. He encourages them to take steps to improve their life […]

-

[…] is the ocean of chaos that renews the Order of Structure. As Jordan Peterson explores in his book Maps of Meaning an order that goes too long without being resubmerged in the […]

[…] we’ve been exploring about recently on the channel it’s a way of understanding the voice of Jordan Peterson in contrast to that of Michel Foucault and the social justice movement. It’s also a good way of situating a lot of the material we have […]

[…] exploration goes back far beyond Jordan Peterson’s Postmodern Neo-Marxists back even beyond Marx himself to the age of the Enlightenment and looks at the evolution of these […]

[…] psychologist Peterson (in stark contrast to the culture warrior Peterson) encourages people to become responsible. He encourages them to take steps to improve their life […]

[…] is the ocean of chaos that renews the Order of Structure. As Jordan Peterson explores in his book Maps of Meaning an order that goes too long without being resubmerged in the […]