At the core of every moral code there is a picture of human nature, a map of the universe, and a version of history. To human nature (of the sort conceived), in a universe (of the kind imagined), after a history (so understood), the rules of the code apply.

— Walter Lippmann

The great poet-philosopher Samuel Coleridge once wrote that “Every man is born an Aristotelian or a Platonist.” He was referring to the same conceptual ground that Thomas Sowell covers in his 1987 work A Conflict of Visions.

One swath of humanity wears Aristotelian goggles; the other wears Platonist ones and these goggles colour everything in the world of their wearers from equality and justice to knowledge, power, peace and war.

This slight alteration in perception is enough to give shape to the dramatically polarised cultural landscape we find ourselves in today. But these conflicting visions account for much more than the 21st century’s culture wars. As Sowell puts it:

Conflicts of interests dominate the short run, but conflicts of visions dominate history.

His exploration goes back far beyond Jordan Peterson’s Postmodern Neo-Marxists back even beyond Marx himself to the age of the Enlightenment and looks at the evolution of these worldviews in two lineages coming from Rousseau and Hobbes.

But this distinction between the Aristotelian vision and the Platonist vision — or as Sowell calls them the “Constrained” and the “Unconstrained” — is not a modern phenomenon; it is a pattern that lies at the core of human history. The one vision is tragic and sees humans as inherently and irrevocably flawed while the other is utopian believing that human nature is perfectible.

Seen through the lens of this distinction the logic of history becomes clearer and we can gain a deeper understanding of everything from the fall of the Roman Republic to the motivations of the French and American Revolutions, the rise of Communism and Fascism and more recently the culture wars, the social justice movement and the rise of the alt-right.

What is a Vision?

Sowell sees visions as being something more than mere emotional drives but less than a paradigm in Kuhn’s sense. Reality, Sowell tells us, is “far too complex to be comprehended by any given mind.” And this is why we need visions. He writes that:

Visions are like maps that guide us through a tangle of bewildering complexities. Like maps, visions have to leave out many concrete features in order to enable us to focus on a few key paths to our goals.

These visions have their own premises and assumptions and their own inherent logic. But despite being logically consistent Sowell says that visions are more like a gut feeling or a hunch than an exercise in logic or factual verification.

The critical phrase for understanding visions is that they are a “sense of causation”. They skew our perception of the world in such a way that we search for a particular type of causation. In a recent instalment we talked about how when something goes wrong the Greek mindset was to blame some petty conflict among the gods while in the Judeo-Christian tradition the mindset was that the blame rested with me — I must have done something to offend the Almighty. These are varying religious visions.

Visions also underpin our empirical explanations of the world — a hunter-gatherer in the Amazon will have one sense of what causes a leaf to move; Newton would have another vision and Einstein another again. These visions are the foundations on which hypotheses and theories are built.

In Sowell’s book and in this article however we are going to focus on the moral, social and economic visions that have a “sense of causation” around the nature of humanity — not just as we are but of our ultimate potential and limitations.

Constrained vs Unconstrained: Human Nature

So then, what are the Constrained and the Unconstrained visions?

The distinction between these two visions comes down to their beliefs around the “capacities and limitations of man”. The moral and mental capacities of humanity are seen very differently by those in the Constrained and Unconstrained traditions. They have their own distinct senses of the nature of humans.

Constrained

In his Leviathan the father of the modern Constrained vision Thomas Hobbes wrote that without the structure of society’s institutions and laws there would be a “bloody war of each against all”. For Hobbes, humanity in a state of nature would be “solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.”

The Constrained vision has its lens fixed squarely on this moral weakness of humanity. The saying “Power corrupts; absolute power corrupts absolutely” is a Constrained one. The intricate checks and balances of the American Constitution were designed to prevent any individual from gaining too much power. Excessive power removes the Hobbesian constraints on an individual and unleashes the “nasty, brutish” human nature that is always lurking beneath the surface.

The ideal society for the Constrained then is the one that best keeps this nasty nature in check. Any projections of the future of humanity and of a reworking of society have to reckon with these limitations of human nature.

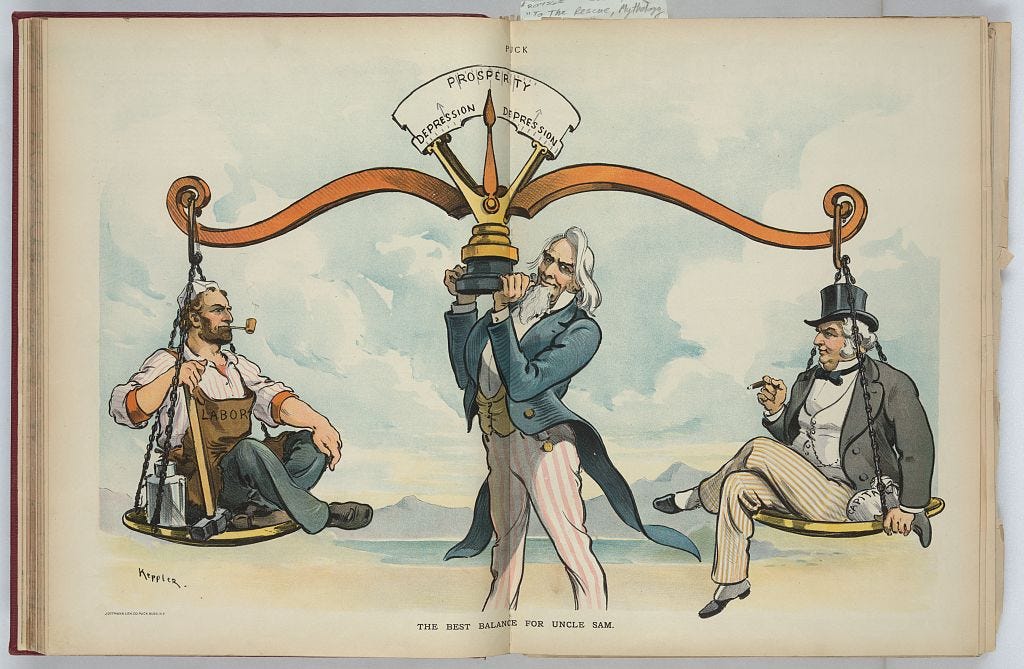

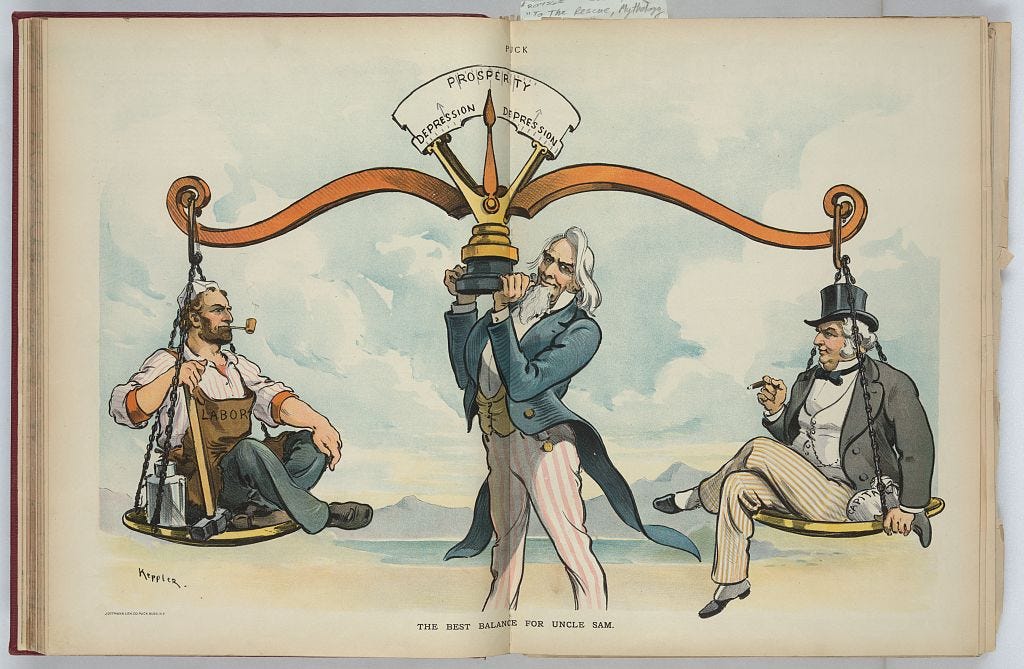

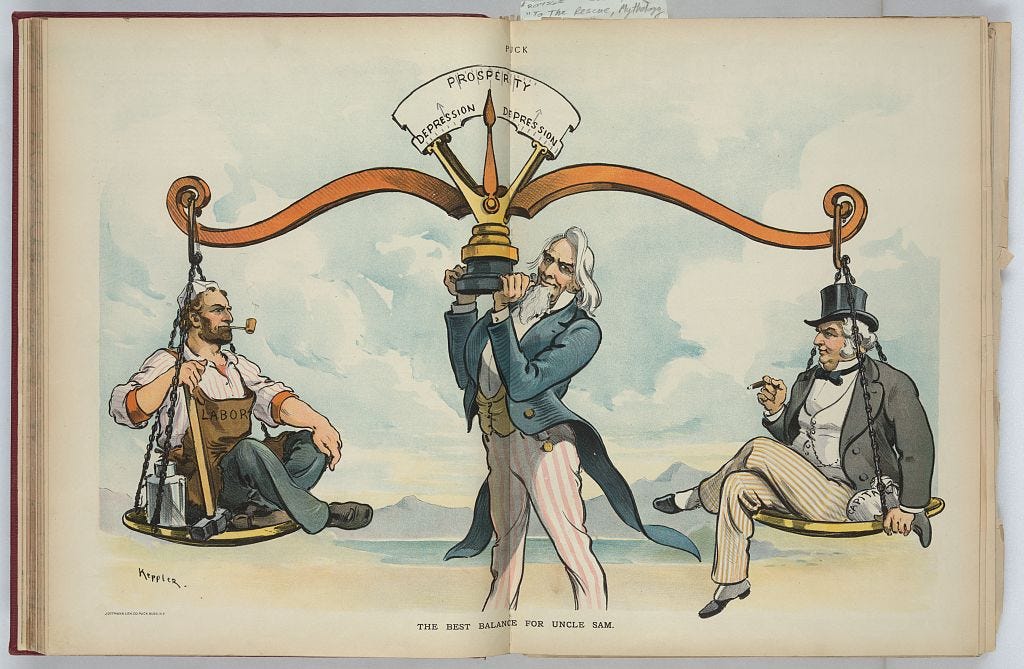

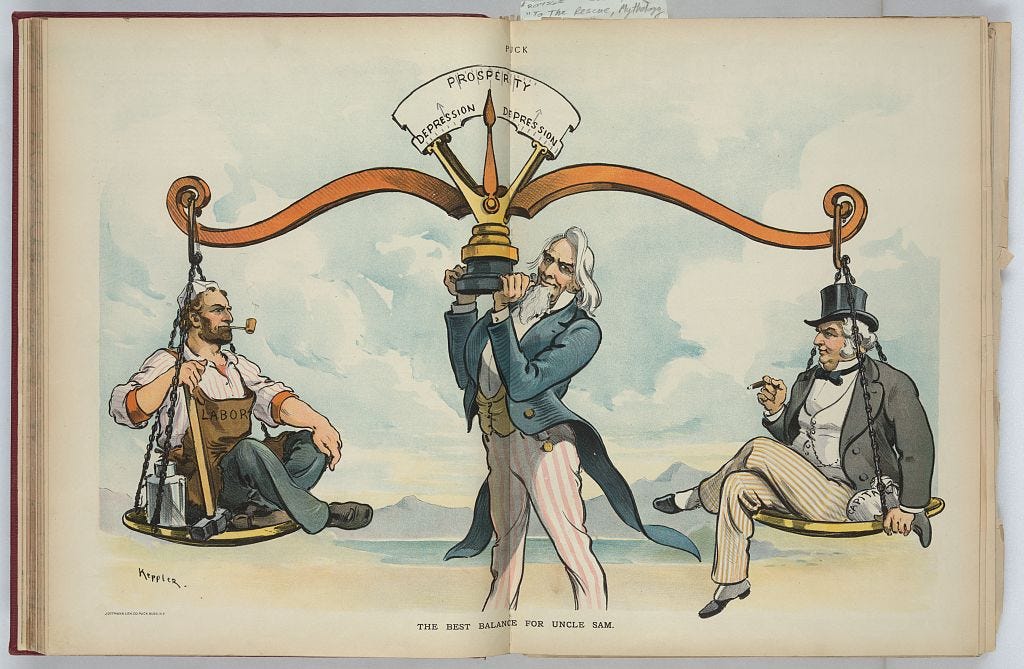

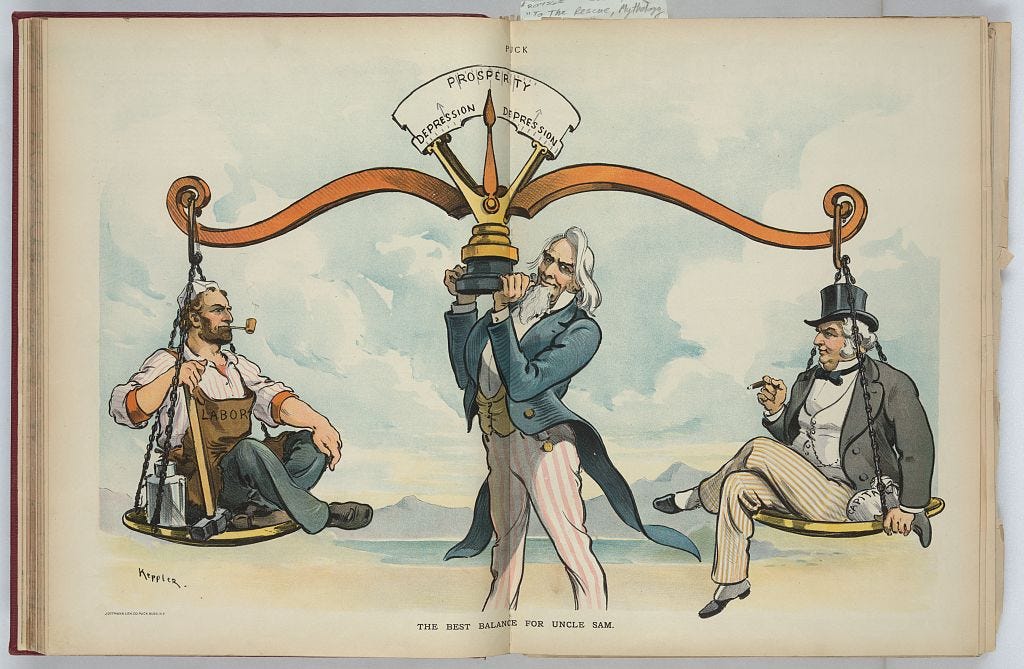

Armed with this vision of human nature, there can be no glorious paradise on this Earth. Since human nature is the problem, there are no solutions. And so, the Constrained vision’s ideal world is one where the best balance is struck whereby the unsavoury aspects of human nature are kept in check while still allowing the greatest degree of individual freedom. As such the highest virtue in the Constrained tradition is prudence.

Unconstrained

The Unconstrained vision sees things very differently. For the Unconstrained, human nature is perfectible. Humanity has incredible potentials but we find ourselves in a system warped by power interests and with cynical incentives laid like carrots all around us. If society could do away with these institutions and power structures that corrupt humanity with scarcity and avarice then the true beauty of human nature could emerge and flourish. With freedom from the low ceiling our society currently places over humanity, our spirits could soar.

The Unconstrained vision asks us to imagine a world where instead of living “lives of quiet desperation” spending most of our time working at jobs we don’t like for people we don’t respect, what if humanity instead worked enough to meet its needs and then focused on flourishing.

There is so much more to being human than the society’s cookie-cutter mould would lead us to believe. We are becoming increasingly alienated from our own natures. Epicurus’s philosophy sought to embrace “contented poverty” and he saw wisdom and friendship as the highest goals of life. His school of philosophy spread across the ancient world and there were Epicurean communes everywhere from Egypt and Syria to Spain and France. The great Roman statesman Cicero who was anything but an Epicurean noted how:

Epicurus, however, in a single household, and one of slender means at that, maintained a whole host of friends, united by a wonderful bond of affection. And this is still a feature of present day Epicureanism.

— Cicero, On Ends (45 BC)

In Walden Henry David Thoreau talked about food, shelter and warmth as the roots of Man. Instead of amplifying these basic needs by spending more time and money on richer food, larger houses and finer clothing:

When he has obtained those things which are necessary to life, there is another alternative than to obtain the superfluities; and that is, to adventure on life now, his vacation from humbler toil having commenced. The soil, it appears, is suited to the seed, for it has sent its radicle downward, and it may now send its shoot upward also with confidence. Why has man rooted himself thus firmly in the earth, but that he may rise in the same proportion into the heavens above?

This is the Unconstrained vision. When Jefferson wrote the words “life liberty and the pursuit of happiness” and the French Revolutionaries proclaimed “liberty equality and fraternity” as their motto, they weren’t thinking of humans as selfish and greedy. They were speaking to the better angels of our nature. This is the focus of the Unconstrained vision — its eyes are fixed on the great heights to which humans can soar.

The Unconstrained vision then is a utopian vision. With a dream of a more perfect world, the Unconstrained vision doesn’t think in terms of trade-offs but in terms of solutions. The Unconstrained believe in our ability to reach an Edenic place with a much higher quality of life. As such prudence is far from the highest priority. Instead the Unconstrained vision prizes earnestness and courage.

Constrained vs Unconstrained: Progress

Armed with this vision of human nature, the two visions end up with very different conceptions of change. The sense of how things progress and our role in that progress are in stark contrast between the two visions.

Unconstrained

The Unconstrained vision is individual-oriented. The motto of this vision is Gandhi’s “be the change you want to see in the world.” The better tomorrow is brought to fruition by today’s vanguard. That might be Thoreau in his cabin and the Epicureans in their communities or it might be the literal vanguard in the Marxist-Leninist sense or the brave Anti-Racist or Social Justice activist.

The bottom line is that for the Unconstrained, change isn’t going to come from the ossified power structures that have been captured by the greedy and corrupt elite. It is us the people that must bring about change.

With its individualist orientation, intention is an important aspect of the Unconstrained vision. Whether an individual is earnest and working in good faith to bring about a better world is essential. We need to know that they are not simply seeking their own selfish ends. We must be better than what we are struggling against. The shadow of this emphasis on intention is the danger of self-righteousness and moral puritanism.

Constrained

In direct contrast, the Constrained vision puts little emphasis on intention. The great Scottish philosopher Adam Smith was, despite being a Constrained thinker and the father of modern economics, highly suspicious of capitalists. He said that they

seldom meet together, even for merriment or diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.

But Smith wasn’t worried about these ill-intentions of the capitalists because he believed that the capitalist only does good when he “intends his own gain” and that the capitalist does more for society that way than “when he really intends to promote it.”

But if there’s one thing that Smith is more suspicious of than capitalists, it’s philosopher-kings. He spoke disparagingly of the “man of the system” who

wise in his own conceit […] seems to imagine that he can arrange the different members of a great society with as much ease as the hand arranges the different pieces upon a chess-board.

This is a really interesting difference then. Where the Unconstrained are focused on the individual and their intentions, the Constrained vision sees these intentions as irrelevant. If anything these intentions get in the way.

But what exactly do they get in the way of? Instead of individual intentions or greedy capitalists, Smith trusts in the murmuration of the dynamic system of the economy. This faith in complexity is the hallmark of the Constrained vision according to Sowell. Instead of looking at individual intentions, the Constrained look at the wisdom of systemic processes.

Since Darwin, the Constrained vision has taken up the language of evolution. The argument is that society is far too complex for any individual to understand — to use Smith’s analogy it is not a chess board that one can simply manoeuvre pieces on.

This vision instead looks at the innumerable intentions and actions that together give rise to a symphony of emergent order. Attempts at tearing up the current society to build a better one seem hopelessly naive for those with this vision.

Our society is something evolved; there is great time-tested wisdom embedded in the cultural practices — in our, habits and our institutions. Instead of starting from scratch and blueprinting a new society, the Constrained vision believes that we should treat problems in our society as we would treat wounds in our father. We can’t ignore them but the fact that there is a problem shouldn’t be a jumping-off point for radical experimentation. We should be very careful and attentive in what we do.

Of course where the shadow of the Unconstrained vision was moral puritanism, the shadow of the Constrained vision is rigidity. It is easy to hide behind the great murmuration of systemic movements as the agent of change but this is to make a mereological fallacy. The whole that is the murmuration is composed of a million individual birds. Change still comes through the actions of individuals and it may just be that it is the Unconstrained that introduce the element of change and that it is the tension between the Constrained and the Unconstrained that brings about the slow and steady evolution. Left to its own devices the Constrained vision may succumb to rigidity and inertia.

Summary:

To summarise then, the Unconstrained vision believes that we can and should make a better world. Those with this vision believe that humanity could be doing far better. The systems and institutions that we currently inhabit withhold us from our true and wonderful potentials. Utopia is a realisable dream in which all humans might live according to the better angels of our nature in harmony, equality and freedom.

In contrast, the Constrained vision focuses on the negative side of human nature. It sees the pervasive selfishness and greed of humans not as an exception but as the rule. The only thing that keeps these dangerous aspects of human nature in check are the structures, laws and institutions that have evolved over the centuries. The Constrained are mindful of the distribution of power. This vision believes we must be very fearful of giving any individual or group of individuals unlimited power to overhaul society in their ideal image. The horrors of the Gulags and the Concentration camps speak to this danger of the Unconstrained leadership being given undiluted control to bring about their mandate. We can see the same in the executions of Sulla in Ancient Rome followed two generations later by the end of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire. Progress in society comes through an evolution of these societal structures. This evolution comes out of a concatenation of systemic processes that are greater than any individual.

An Attempt at Synthesis

These visions have been in a tug of war for centuries and the question is how are we to square them? In A Conflict of Visions Sowell does his utmost to present both visions in a balanced fashion but nevertheless his bias for the Constrained vision comes through strongly. While he doesn’t make a strawman of the Unconstrained vision, his portrayal certainly wouldn’t pass an Ideological Turing Test whereby those with the Unconstrained vision would mistake him for one of their own.

In the run-up to the 2008 US Presidential elections, Sowell was interviewed about Obama and the Unconstrained vision and he said that:

“The unconstrained vision is really an elitist vision,” Sowell explains. “This man [Obama] really does believe that he can change the world. And people like that are infinitely more dangerous than mere crooked politicians.”

So Sowell is very far from being partial to the Unconstrained vision. He sees it only as dangerous and elitist and as such we have to be mindful of this bias when reading A Conflict of Visions.

It seems that for him the ideal case would be the triumph of the Constrained vision. Of course Sowell doesn’t believe that such an ideal world is going to come to fruition but that would certainly seem to be his preference.

But given that what we have here are two pragmatic maps of reality that have stood the test of time, we must suspect that there are areas where each of them are immensely valuable and so the question becomes how to reconcile these visions so that we can integrate their best parts.

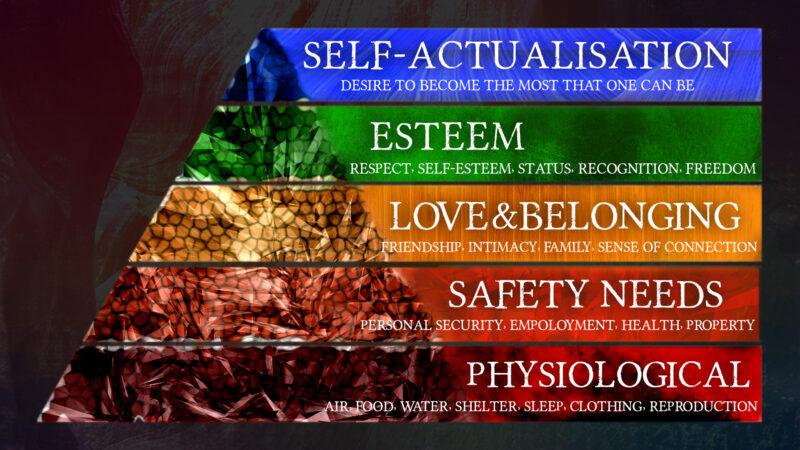

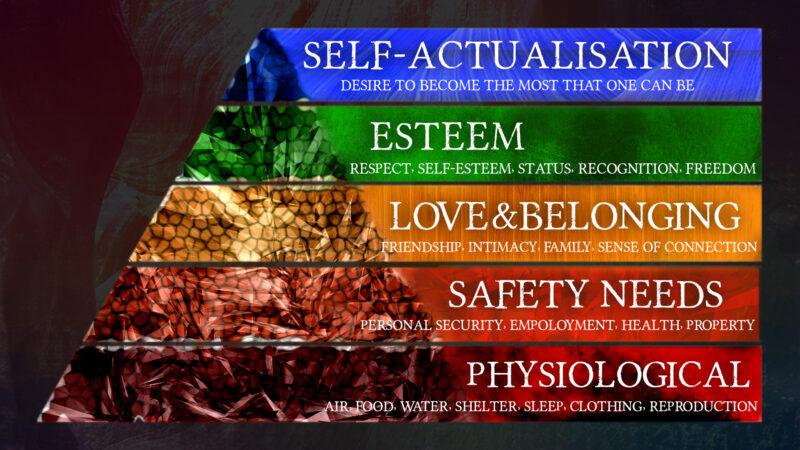

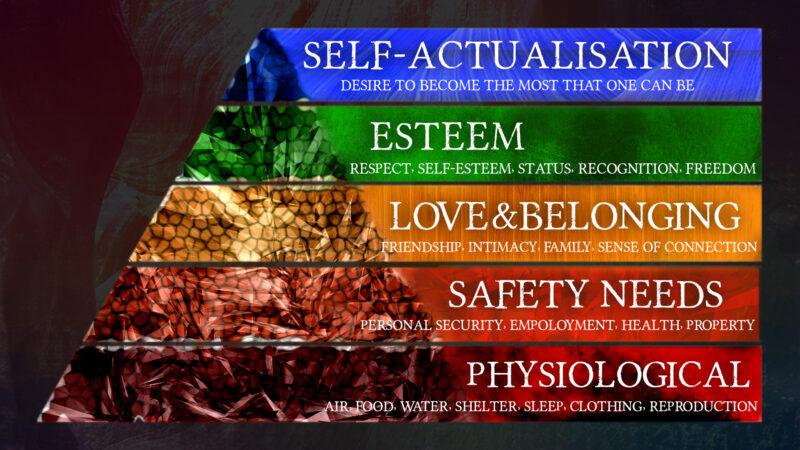

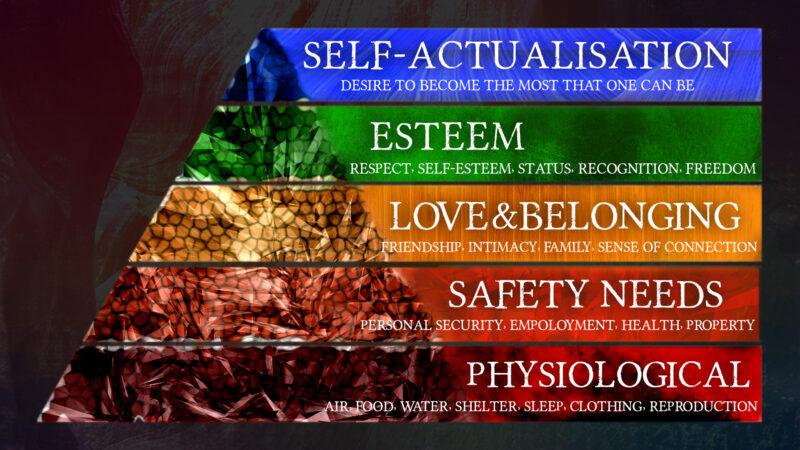

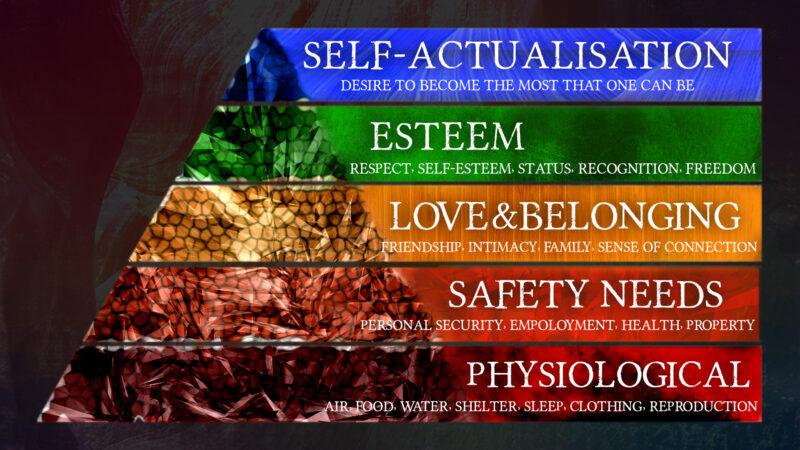

A fruitful starting point is to look at them through a developmental lens. Seen through the lens of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs we can see that they are focused on opposite ends of the human experience.

As every post-apocalyptic movie and tv show knows, when society collapses it’s every man and woman for themselves. Scarcity reveals the “poore, nasty, brutish,” human nature. Yesterday you may have been focused on relationships and success, today you’re just thinking about food, water and warmth.

Civilisation, as Thomas Hobbes argues in his Leviathan, is the dam that holds back these impulses. When people’s basic needs are met, this darkness in human nature is contained and our more pro-social impulses can be emphasised.

The Unconstrained vision on the other hand is focused on the pinnacle of Maslow’s hierarchy: self-actualisation.

For the self-actualising individual whose lower needs are met, money and worldly success are secondary to a higher need. And seen through this lens the philosophies of Marx, Epicurus and Thoreau seem to speak to a deeper truth about humanity. Humans are seen to be fundamentally good creatures that are as in Plato’s allegory, trapped in a cave staring at shadows cast on a wall by a fire rather than out in the real world where the sun shines. We have been alienated from our true natures by the warped landscape of society. There is a sense of a higher truth that most people seem to be missing out on. There is a better world that we want to share with others.

But of course just like the Constrained view, this is a partial truth. Where the Constrained vision are focused on the roots, the Unconstrained see only the flowers and the fruits. But humans are neither entirely good nor bad. As Solzhenitsyn put it “the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.”

The Constrained vision seeks to maintain the stable foundation of the society. It seeks to protect us from ourselves. Society is the dam that restrains the darkness of human nature. And with this darkness stunted, the brighter sides of our nature can develop and grow.

Living in a peaceful and prosperous society, we see people growing more compassionate and wanting to make a world that is founded on these better angels of our nature. And if we are living in a peaceful society and are relatively prosperous it is possible for us to forget about the darkness in human nature. This darkness of human nature is always waiting at the door and when there is a disruption in the order of things it pours into the crevices as we saw with the horrors that followed the French Revolution, the Soviet Revolution and the rise of the Nazis from the First World War and the Wall Street Crash.

This Unconstrained for whatever personal, historical or socioeconomic reasons, are sitting on a higher perch in Maslow’s hierarchy. Like Lao-Tzu they tell us that “Man does not live by bread alone.” But as the history books dotted with Bread Riots would remind us: Without bread man doesn’t live at all and he may even kill other men on the way to his grave.

4 Comments

Leave A Comment

At the core of every moral code there is a picture of human nature, a map of the universe, and a version of history. To human nature (of the sort conceived), in a universe (of the kind imagined), after a history (so understood), the rules of the code apply.

— Walter Lippmann

The great poet-philosopher Samuel Coleridge once wrote that “Every man is born an Aristotelian or a Platonist.” He was referring to the same conceptual ground that Thomas Sowell covers in his 1987 work A Conflict of Visions.

One swath of humanity wears Aristotelian goggles; the other wears Platonist ones and these goggles colour everything in the world of their wearers from equality and justice to knowledge, power, peace and war.

This slight alteration in perception is enough to give shape to the dramatically polarised cultural landscape we find ourselves in today. But these conflicting visions account for much more than the 21st century’s culture wars. As Sowell puts it:

Conflicts of interests dominate the short run, but conflicts of visions dominate history.

His exploration goes back far beyond Jordan Peterson’s Postmodern Neo-Marxists back even beyond Marx himself to the age of the Enlightenment and looks at the evolution of these worldviews in two lineages coming from Rousseau and Hobbes.

But this distinction between the Aristotelian vision and the Platonist vision — or as Sowell calls them the “Constrained” and the “Unconstrained” — is not a modern phenomenon; it is a pattern that lies at the core of human history. The one vision is tragic and sees humans as inherently and irrevocably flawed while the other is utopian believing that human nature is perfectible.

Seen through the lens of this distinction the logic of history becomes clearer and we can gain a deeper understanding of everything from the fall of the Roman Republic to the motivations of the French and American Revolutions, the rise of Communism and Fascism and more recently the culture wars, the social justice movement and the rise of the alt-right.

What is a Vision?

Sowell sees visions as being something more than mere emotional drives but less than a paradigm in Kuhn’s sense. Reality, Sowell tells us, is “far too complex to be comprehended by any given mind.” And this is why we need visions. He writes that:

Visions are like maps that guide us through a tangle of bewildering complexities. Like maps, visions have to leave out many concrete features in order to enable us to focus on a few key paths to our goals.

These visions have their own premises and assumptions and their own inherent logic. But despite being logically consistent Sowell says that visions are more like a gut feeling or a hunch than an exercise in logic or factual verification.

The critical phrase for understanding visions is that they are a “sense of causation”. They skew our perception of the world in such a way that we search for a particular type of causation. In a recent instalment we talked about how when something goes wrong the Greek mindset was to blame some petty conflict among the gods while in the Judeo-Christian tradition the mindset was that the blame rested with me — I must have done something to offend the Almighty. These are varying religious visions.

Visions also underpin our empirical explanations of the world — a hunter-gatherer in the Amazon will have one sense of what causes a leaf to move; Newton would have another vision and Einstein another again. These visions are the foundations on which hypotheses and theories are built.

In Sowell’s book and in this article however we are going to focus on the moral, social and economic visions that have a “sense of causation” around the nature of humanity — not just as we are but of our ultimate potential and limitations.

Constrained vs Unconstrained: Human Nature

So then, what are the Constrained and the Unconstrained visions?

The distinction between these two visions comes down to their beliefs around the “capacities and limitations of man”. The moral and mental capacities of humanity are seen very differently by those in the Constrained and Unconstrained traditions. They have their own distinct senses of the nature of humans.

Constrained

In his Leviathan the father of the modern Constrained vision Thomas Hobbes wrote that without the structure of society’s institutions and laws there would be a “bloody war of each against all”. For Hobbes, humanity in a state of nature would be “solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.”

The Constrained vision has its lens fixed squarely on this moral weakness of humanity. The saying “Power corrupts; absolute power corrupts absolutely” is a Constrained one. The intricate checks and balances of the American Constitution were designed to prevent any individual from gaining too much power. Excessive power removes the Hobbesian constraints on an individual and unleashes the “nasty, brutish” human nature that is always lurking beneath the surface.

The ideal society for the Constrained then is the one that best keeps this nasty nature in check. Any projections of the future of humanity and of a reworking of society have to reckon with these limitations of human nature.

Armed with this vision of human nature, there can be no glorious paradise on this Earth. Since human nature is the problem, there are no solutions. And so, the Constrained vision’s ideal world is one where the best balance is struck whereby the unsavoury aspects of human nature are kept in check while still allowing the greatest degree of individual freedom. As such the highest virtue in the Constrained tradition is prudence.

Unconstrained

The Unconstrained vision sees things very differently. For the Unconstrained, human nature is perfectible. Humanity has incredible potentials but we find ourselves in a system warped by power interests and with cynical incentives laid like carrots all around us. If society could do away with these institutions and power structures that corrupt humanity with scarcity and avarice then the true beauty of human nature could emerge and flourish. With freedom from the low ceiling our society currently places over humanity, our spirits could soar.

The Unconstrained vision asks us to imagine a world where instead of living “lives of quiet desperation” spending most of our time working at jobs we don’t like for people we don’t respect, what if humanity instead worked enough to meet its needs and then focused on flourishing.

There is so much more to being human than the society’s cookie-cutter mould would lead us to believe. We are becoming increasingly alienated from our own natures. Epicurus’s philosophy sought to embrace “contented poverty” and he saw wisdom and friendship as the highest goals of life. His school of philosophy spread across the ancient world and there were Epicurean communes everywhere from Egypt and Syria to Spain and France. The great Roman statesman Cicero who was anything but an Epicurean noted how:

Epicurus, however, in a single household, and one of slender means at that, maintained a whole host of friends, united by a wonderful bond of affection. And this is still a feature of present day Epicureanism.

— Cicero, On Ends (45 BC)

In Walden Henry David Thoreau talked about food, shelter and warmth as the roots of Man. Instead of amplifying these basic needs by spending more time and money on richer food, larger houses and finer clothing:

When he has obtained those things which are necessary to life, there is another alternative than to obtain the superfluities; and that is, to adventure on life now, his vacation from humbler toil having commenced. The soil, it appears, is suited to the seed, for it has sent its radicle downward, and it may now send its shoot upward also with confidence. Why has man rooted himself thus firmly in the earth, but that he may rise in the same proportion into the heavens above?

This is the Unconstrained vision. When Jefferson wrote the words “life liberty and the pursuit of happiness” and the French Revolutionaries proclaimed “liberty equality and fraternity” as their motto, they weren’t thinking of humans as selfish and greedy. They were speaking to the better angels of our nature. This is the focus of the Unconstrained vision — its eyes are fixed on the great heights to which humans can soar.

The Unconstrained vision then is a utopian vision. With a dream of a more perfect world, the Unconstrained vision doesn’t think in terms of trade-offs but in terms of solutions. The Unconstrained believe in our ability to reach an Edenic place with a much higher quality of life. As such prudence is far from the highest priority. Instead the Unconstrained vision prizes earnestness and courage.

Constrained vs Unconstrained: Progress

Armed with this vision of human nature, the two visions end up with very different conceptions of change. The sense of how things progress and our role in that progress are in stark contrast between the two visions.

Unconstrained

The Unconstrained vision is individual-oriented. The motto of this vision is Gandhi’s “be the change you want to see in the world.” The better tomorrow is brought to fruition by today’s vanguard. That might be Thoreau in his cabin and the Epicureans in their communities or it might be the literal vanguard in the Marxist-Leninist sense or the brave Anti-Racist or Social Justice activist.

The bottom line is that for the Unconstrained, change isn’t going to come from the ossified power structures that have been captured by the greedy and corrupt elite. It is us the people that must bring about change.

With its individualist orientation, intention is an important aspect of the Unconstrained vision. Whether an individual is earnest and working in good faith to bring about a better world is essential. We need to know that they are not simply seeking their own selfish ends. We must be better than what we are struggling against. The shadow of this emphasis on intention is the danger of self-righteousness and moral puritanism.

Constrained

In direct contrast, the Constrained vision puts little emphasis on intention. The great Scottish philosopher Adam Smith was, despite being a Constrained thinker and the father of modern economics, highly suspicious of capitalists. He said that they

seldom meet together, even for merriment or diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.

But Smith wasn’t worried about these ill-intentions of the capitalists because he believed that the capitalist only does good when he “intends his own gain” and that the capitalist does more for society that way than “when he really intends to promote it.”

But if there’s one thing that Smith is more suspicious of than capitalists, it’s philosopher-kings. He spoke disparagingly of the “man of the system” who

wise in his own conceit […] seems to imagine that he can arrange the different members of a great society with as much ease as the hand arranges the different pieces upon a chess-board.

This is a really interesting difference then. Where the Unconstrained are focused on the individual and their intentions, the Constrained vision sees these intentions as irrelevant. If anything these intentions get in the way.

But what exactly do they get in the way of? Instead of individual intentions or greedy capitalists, Smith trusts in the murmuration of the dynamic system of the economy. This faith in complexity is the hallmark of the Constrained vision according to Sowell. Instead of looking at individual intentions, the Constrained look at the wisdom of systemic processes.

Since Darwin, the Constrained vision has taken up the language of evolution. The argument is that society is far too complex for any individual to understand — to use Smith’s analogy it is not a chess board that one can simply manoeuvre pieces on.

This vision instead looks at the innumerable intentions and actions that together give rise to a symphony of emergent order. Attempts at tearing up the current society to build a better one seem hopelessly naive for those with this vision.

Our society is something evolved; there is great time-tested wisdom embedded in the cultural practices — in our, habits and our institutions. Instead of starting from scratch and blueprinting a new society, the Constrained vision believes that we should treat problems in our society as we would treat wounds in our father. We can’t ignore them but the fact that there is a problem shouldn’t be a jumping-off point for radical experimentation. We should be very careful and attentive in what we do.

Of course where the shadow of the Unconstrained vision was moral puritanism, the shadow of the Constrained vision is rigidity. It is easy to hide behind the great murmuration of systemic movements as the agent of change but this is to make a mereological fallacy. The whole that is the murmuration is composed of a million individual birds. Change still comes through the actions of individuals and it may just be that it is the Unconstrained that introduce the element of change and that it is the tension between the Constrained and the Unconstrained that brings about the slow and steady evolution. Left to its own devices the Constrained vision may succumb to rigidity and inertia.

Summary:

To summarise then, the Unconstrained vision believes that we can and should make a better world. Those with this vision believe that humanity could be doing far better. The systems and institutions that we currently inhabit withhold us from our true and wonderful potentials. Utopia is a realisable dream in which all humans might live according to the better angels of our nature in harmony, equality and freedom.

In contrast, the Constrained vision focuses on the negative side of human nature. It sees the pervasive selfishness and greed of humans not as an exception but as the rule. The only thing that keeps these dangerous aspects of human nature in check are the structures, laws and institutions that have evolved over the centuries. The Constrained are mindful of the distribution of power. This vision believes we must be very fearful of giving any individual or group of individuals unlimited power to overhaul society in their ideal image. The horrors of the Gulags and the Concentration camps speak to this danger of the Unconstrained leadership being given undiluted control to bring about their mandate. We can see the same in the executions of Sulla in Ancient Rome followed two generations later by the end of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire. Progress in society comes through an evolution of these societal structures. This evolution comes out of a concatenation of systemic processes that are greater than any individual.

An Attempt at Synthesis

These visions have been in a tug of war for centuries and the question is how are we to square them? In A Conflict of Visions Sowell does his utmost to present both visions in a balanced fashion but nevertheless his bias for the Constrained vision comes through strongly. While he doesn’t make a strawman of the Unconstrained vision, his portrayal certainly wouldn’t pass an Ideological Turing Test whereby those with the Unconstrained vision would mistake him for one of their own.

In the run-up to the 2008 US Presidential elections, Sowell was interviewed about Obama and the Unconstrained vision and he said that:

“The unconstrained vision is really an elitist vision,” Sowell explains. “This man [Obama] really does believe that he can change the world. And people like that are infinitely more dangerous than mere crooked politicians.”

So Sowell is very far from being partial to the Unconstrained vision. He sees it only as dangerous and elitist and as such we have to be mindful of this bias when reading A Conflict of Visions.

It seems that for him the ideal case would be the triumph of the Constrained vision. Of course Sowell doesn’t believe that such an ideal world is going to come to fruition but that would certainly seem to be his preference.

But given that what we have here are two pragmatic maps of reality that have stood the test of time, we must suspect that there are areas where each of them are immensely valuable and so the question becomes how to reconcile these visions so that we can integrate their best parts.

A fruitful starting point is to look at them through a developmental lens. Seen through the lens of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs we can see that they are focused on opposite ends of the human experience.

As every post-apocalyptic movie and tv show knows, when society collapses it’s every man and woman for themselves. Scarcity reveals the “poore, nasty, brutish,” human nature. Yesterday you may have been focused on relationships and success, today you’re just thinking about food, water and warmth.

Civilisation, as Thomas Hobbes argues in his Leviathan, is the dam that holds back these impulses. When people’s basic needs are met, this darkness in human nature is contained and our more pro-social impulses can be emphasised.

The Unconstrained vision on the other hand is focused on the pinnacle of Maslow’s hierarchy: self-actualisation.

For the self-actualising individual whose lower needs are met, money and worldly success are secondary to a higher need. And seen through this lens the philosophies of Marx, Epicurus and Thoreau seem to speak to a deeper truth about humanity. Humans are seen to be fundamentally good creatures that are as in Plato’s allegory, trapped in a cave staring at shadows cast on a wall by a fire rather than out in the real world where the sun shines. We have been alienated from our true natures by the warped landscape of society. There is a sense of a higher truth that most people seem to be missing out on. There is a better world that we want to share with others.

But of course just like the Constrained view, this is a partial truth. Where the Constrained vision are focused on the roots, the Unconstrained see only the flowers and the fruits. But humans are neither entirely good nor bad. As Solzhenitsyn put it “the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.”

The Constrained vision seeks to maintain the stable foundation of the society. It seeks to protect us from ourselves. Society is the dam that restrains the darkness of human nature. And with this darkness stunted, the brighter sides of our nature can develop and grow.

Living in a peaceful and prosperous society, we see people growing more compassionate and wanting to make a world that is founded on these better angels of our nature. And if we are living in a peaceful society and are relatively prosperous it is possible for us to forget about the darkness in human nature. This darkness of human nature is always waiting at the door and when there is a disruption in the order of things it pours into the crevices as we saw with the horrors that followed the French Revolution, the Soviet Revolution and the rise of the Nazis from the First World War and the Wall Street Crash.

This Unconstrained for whatever personal, historical or socioeconomic reasons, are sitting on a higher perch in Maslow’s hierarchy. Like Lao-Tzu they tell us that “Man does not live by bread alone.” But as the history books dotted with Bread Riots would remind us: Without bread man doesn’t live at all and he may even kill other men on the way to his grave.

4 Comments

-

Is it really a binary choice of either/or? So is either vision the better of the two, liberalism (unconstrained) or conservatism (constrained), for they both have their merits and demerits? I’d say that we need to keep a healthy tension between them both. This is akin to Nietzsche’s idea about the Apollonian and Dionysian principles that gave us the ancient Greek culture. The Apollonian principle, being grounded in rationality (constrained), is the structure which contains the energy and vitality of the irrational Dionysian principle (unconstrained).

Therefore, unchallenged conservatism will eventually lead to stagnation and become counterproductive to the onward development of culture. Similarly, unfettered liberalism will inevitably lead to antinomianism and moral chaos. Individual freedom must be channeled through a moral container in order for it to bear the authentic fruits of progress, otherwise the tendency towards degeneracy will result in a regression to a lower level of consciousness.

All of the above can be clearly seen in the parable of the parable of the Prodigal Son from the New Testament who allowed his unconstrained Dionysian (irrational) side to lead him into a life of profligate immorality and spiritual bankruptcy. But having come to his senses he then adopts an Apollonian constrained (rational) perspective which ultimately leads him to a better life of deeper meaning and purpose.

The trick here then is to avoid extremes because nature tends to abhor large imbalances as eventually there always comes an explosive correction that brings about a greater balance. Conservatives can adopt some of the energy and vitality of liberalism because it has a strong moral and traditional structure by which to channel it. Liberalism can likewise flow freely and constructively by working through conservative structures and principles.

Any system of values or ideas must avoid becoming ossified in a rigid tradition otherwise it becomes in danger of losing relevance in a culture that is ever emerging. So in this way we must let ‘the dead bury their own dead’ for life is vibrant and emergent.

In the final analysis, we come to understand that our freedom(s) must be wisely enacted if we are to avoid the extremism at either end of the moral spectrum. It is prudent to avoid becoming stifled by unyielding strict adherence to the cold letter of constraint (morality), and yet live vibrantly via the established trusted structures that morality embodies.

-

It would be wonderful if people could understand that it is the tension between the two – an eternal osculation … that allows humanity to thrive in the balance. If we saw our situation as rowing a canoe down a river (which requires paddling on the left and the right and making adjustments as currents and bends in the river arise) … then we could start appreciating each other and working together to solve problems. This is the antidote to being locked in partisanship and trying to destroy the other in an effort to prove ourselves right (while ultimately destroying ourselves and all good things in the process).

-

[…] those of you who have read the instalment on Thomas Sowell’s A Conflict of Visions this will bring to mind the contrast between the Hobbesian Constrained Vision and the […]

Leave A Comment

At the core of every moral code there is a picture of human nature, a map of the universe, and a version of history. To human nature (of the sort conceived), in a universe (of the kind imagined), after a history (so understood), the rules of the code apply.

— Walter Lippmann

The great poet-philosopher Samuel Coleridge once wrote that “Every man is born an Aristotelian or a Platonist.” He was referring to the same conceptual ground that Thomas Sowell covers in his 1987 work A Conflict of Visions.

One swath of humanity wears Aristotelian goggles; the other wears Platonist ones and these goggles colour everything in the world of their wearers from equality and justice to knowledge, power, peace and war.

This slight alteration in perception is enough to give shape to the dramatically polarised cultural landscape we find ourselves in today. But these conflicting visions account for much more than the 21st century’s culture wars. As Sowell puts it:

Conflicts of interests dominate the short run, but conflicts of visions dominate history.

His exploration goes back far beyond Jordan Peterson’s Postmodern Neo-Marxists back even beyond Marx himself to the age of the Enlightenment and looks at the evolution of these worldviews in two lineages coming from Rousseau and Hobbes.

But this distinction between the Aristotelian vision and the Platonist vision — or as Sowell calls them the “Constrained” and the “Unconstrained” — is not a modern phenomenon; it is a pattern that lies at the core of human history. The one vision is tragic and sees humans as inherently and irrevocably flawed while the other is utopian believing that human nature is perfectible.

Seen through the lens of this distinction the logic of history becomes clearer and we can gain a deeper understanding of everything from the fall of the Roman Republic to the motivations of the French and American Revolutions, the rise of Communism and Fascism and more recently the culture wars, the social justice movement and the rise of the alt-right.

What is a Vision?

Sowell sees visions as being something more than mere emotional drives but less than a paradigm in Kuhn’s sense. Reality, Sowell tells us, is “far too complex to be comprehended by any given mind.” And this is why we need visions. He writes that:

Visions are like maps that guide us through a tangle of bewildering complexities. Like maps, visions have to leave out many concrete features in order to enable us to focus on a few key paths to our goals.

These visions have their own premises and assumptions and their own inherent logic. But despite being logically consistent Sowell says that visions are more like a gut feeling or a hunch than an exercise in logic or factual verification.

The critical phrase for understanding visions is that they are a “sense of causation”. They skew our perception of the world in such a way that we search for a particular type of causation. In a recent instalment we talked about how when something goes wrong the Greek mindset was to blame some petty conflict among the gods while in the Judeo-Christian tradition the mindset was that the blame rested with me — I must have done something to offend the Almighty. These are varying religious visions.

Visions also underpin our empirical explanations of the world — a hunter-gatherer in the Amazon will have one sense of what causes a leaf to move; Newton would have another vision and Einstein another again. These visions are the foundations on which hypotheses and theories are built.

In Sowell’s book and in this article however we are going to focus on the moral, social and economic visions that have a “sense of causation” around the nature of humanity — not just as we are but of our ultimate potential and limitations.

Constrained vs Unconstrained: Human Nature

So then, what are the Constrained and the Unconstrained visions?

The distinction between these two visions comes down to their beliefs around the “capacities and limitations of man”. The moral and mental capacities of humanity are seen very differently by those in the Constrained and Unconstrained traditions. They have their own distinct senses of the nature of humans.

Constrained

In his Leviathan the father of the modern Constrained vision Thomas Hobbes wrote that without the structure of society’s institutions and laws there would be a “bloody war of each against all”. For Hobbes, humanity in a state of nature would be “solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.”

The Constrained vision has its lens fixed squarely on this moral weakness of humanity. The saying “Power corrupts; absolute power corrupts absolutely” is a Constrained one. The intricate checks and balances of the American Constitution were designed to prevent any individual from gaining too much power. Excessive power removes the Hobbesian constraints on an individual and unleashes the “nasty, brutish” human nature that is always lurking beneath the surface.

The ideal society for the Constrained then is the one that best keeps this nasty nature in check. Any projections of the future of humanity and of a reworking of society have to reckon with these limitations of human nature.

Armed with this vision of human nature, there can be no glorious paradise on this Earth. Since human nature is the problem, there are no solutions. And so, the Constrained vision’s ideal world is one where the best balance is struck whereby the unsavoury aspects of human nature are kept in check while still allowing the greatest degree of individual freedom. As such the highest virtue in the Constrained tradition is prudence.

Unconstrained

The Unconstrained vision sees things very differently. For the Unconstrained, human nature is perfectible. Humanity has incredible potentials but we find ourselves in a system warped by power interests and with cynical incentives laid like carrots all around us. If society could do away with these institutions and power structures that corrupt humanity with scarcity and avarice then the true beauty of human nature could emerge and flourish. With freedom from the low ceiling our society currently places over humanity, our spirits could soar.

The Unconstrained vision asks us to imagine a world where instead of living “lives of quiet desperation” spending most of our time working at jobs we don’t like for people we don’t respect, what if humanity instead worked enough to meet its needs and then focused on flourishing.

There is so much more to being human than the society’s cookie-cutter mould would lead us to believe. We are becoming increasingly alienated from our own natures. Epicurus’s philosophy sought to embrace “contented poverty” and he saw wisdom and friendship as the highest goals of life. His school of philosophy spread across the ancient world and there were Epicurean communes everywhere from Egypt and Syria to Spain and France. The great Roman statesman Cicero who was anything but an Epicurean noted how:

Epicurus, however, in a single household, and one of slender means at that, maintained a whole host of friends, united by a wonderful bond of affection. And this is still a feature of present day Epicureanism.

— Cicero, On Ends (45 BC)

In Walden Henry David Thoreau talked about food, shelter and warmth as the roots of Man. Instead of amplifying these basic needs by spending more time and money on richer food, larger houses and finer clothing:

When he has obtained those things which are necessary to life, there is another alternative than to obtain the superfluities; and that is, to adventure on life now, his vacation from humbler toil having commenced. The soil, it appears, is suited to the seed, for it has sent its radicle downward, and it may now send its shoot upward also with confidence. Why has man rooted himself thus firmly in the earth, but that he may rise in the same proportion into the heavens above?

This is the Unconstrained vision. When Jefferson wrote the words “life liberty and the pursuit of happiness” and the French Revolutionaries proclaimed “liberty equality and fraternity” as their motto, they weren’t thinking of humans as selfish and greedy. They were speaking to the better angels of our nature. This is the focus of the Unconstrained vision — its eyes are fixed on the great heights to which humans can soar.

The Unconstrained vision then is a utopian vision. With a dream of a more perfect world, the Unconstrained vision doesn’t think in terms of trade-offs but in terms of solutions. The Unconstrained believe in our ability to reach an Edenic place with a much higher quality of life. As such prudence is far from the highest priority. Instead the Unconstrained vision prizes earnestness and courage.

Constrained vs Unconstrained: Progress

Armed with this vision of human nature, the two visions end up with very different conceptions of change. The sense of how things progress and our role in that progress are in stark contrast between the two visions.

Unconstrained

The Unconstrained vision is individual-oriented. The motto of this vision is Gandhi’s “be the change you want to see in the world.” The better tomorrow is brought to fruition by today’s vanguard. That might be Thoreau in his cabin and the Epicureans in their communities or it might be the literal vanguard in the Marxist-Leninist sense or the brave Anti-Racist or Social Justice activist.

The bottom line is that for the Unconstrained, change isn’t going to come from the ossified power structures that have been captured by the greedy and corrupt elite. It is us the people that must bring about change.

With its individualist orientation, intention is an important aspect of the Unconstrained vision. Whether an individual is earnest and working in good faith to bring about a better world is essential. We need to know that they are not simply seeking their own selfish ends. We must be better than what we are struggling against. The shadow of this emphasis on intention is the danger of self-righteousness and moral puritanism.

Constrained

In direct contrast, the Constrained vision puts little emphasis on intention. The great Scottish philosopher Adam Smith was, despite being a Constrained thinker and the father of modern economics, highly suspicious of capitalists. He said that they

seldom meet together, even for merriment or diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.

But Smith wasn’t worried about these ill-intentions of the capitalists because he believed that the capitalist only does good when he “intends his own gain” and that the capitalist does more for society that way than “when he really intends to promote it.”

But if there’s one thing that Smith is more suspicious of than capitalists, it’s philosopher-kings. He spoke disparagingly of the “man of the system” who

wise in his own conceit […] seems to imagine that he can arrange the different members of a great society with as much ease as the hand arranges the different pieces upon a chess-board.

This is a really interesting difference then. Where the Unconstrained are focused on the individual and their intentions, the Constrained vision sees these intentions as irrelevant. If anything these intentions get in the way.

But what exactly do they get in the way of? Instead of individual intentions or greedy capitalists, Smith trusts in the murmuration of the dynamic system of the economy. This faith in complexity is the hallmark of the Constrained vision according to Sowell. Instead of looking at individual intentions, the Constrained look at the wisdom of systemic processes.

Since Darwin, the Constrained vision has taken up the language of evolution. The argument is that society is far too complex for any individual to understand — to use Smith’s analogy it is not a chess board that one can simply manoeuvre pieces on.

This vision instead looks at the innumerable intentions and actions that together give rise to a symphony of emergent order. Attempts at tearing up the current society to build a better one seem hopelessly naive for those with this vision.

Our society is something evolved; there is great time-tested wisdom embedded in the cultural practices — in our, habits and our institutions. Instead of starting from scratch and blueprinting a new society, the Constrained vision believes that we should treat problems in our society as we would treat wounds in our father. We can’t ignore them but the fact that there is a problem shouldn’t be a jumping-off point for radical experimentation. We should be very careful and attentive in what we do.

Of course where the shadow of the Unconstrained vision was moral puritanism, the shadow of the Constrained vision is rigidity. It is easy to hide behind the great murmuration of systemic movements as the agent of change but this is to make a mereological fallacy. The whole that is the murmuration is composed of a million individual birds. Change still comes through the actions of individuals and it may just be that it is the Unconstrained that introduce the element of change and that it is the tension between the Constrained and the Unconstrained that brings about the slow and steady evolution. Left to its own devices the Constrained vision may succumb to rigidity and inertia.

Summary:

To summarise then, the Unconstrained vision believes that we can and should make a better world. Those with this vision believe that humanity could be doing far better. The systems and institutions that we currently inhabit withhold us from our true and wonderful potentials. Utopia is a realisable dream in which all humans might live according to the better angels of our nature in harmony, equality and freedom.

In contrast, the Constrained vision focuses on the negative side of human nature. It sees the pervasive selfishness and greed of humans not as an exception but as the rule. The only thing that keeps these dangerous aspects of human nature in check are the structures, laws and institutions that have evolved over the centuries. The Constrained are mindful of the distribution of power. This vision believes we must be very fearful of giving any individual or group of individuals unlimited power to overhaul society in their ideal image. The horrors of the Gulags and the Concentration camps speak to this danger of the Unconstrained leadership being given undiluted control to bring about their mandate. We can see the same in the executions of Sulla in Ancient Rome followed two generations later by the end of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire. Progress in society comes through an evolution of these societal structures. This evolution comes out of a concatenation of systemic processes that are greater than any individual.

An Attempt at Synthesis

These visions have been in a tug of war for centuries and the question is how are we to square them? In A Conflict of Visions Sowell does his utmost to present both visions in a balanced fashion but nevertheless his bias for the Constrained vision comes through strongly. While he doesn’t make a strawman of the Unconstrained vision, his portrayal certainly wouldn’t pass an Ideological Turing Test whereby those with the Unconstrained vision would mistake him for one of their own.

In the run-up to the 2008 US Presidential elections, Sowell was interviewed about Obama and the Unconstrained vision and he said that:

“The unconstrained vision is really an elitist vision,” Sowell explains. “This man [Obama] really does believe that he can change the world. And people like that are infinitely more dangerous than mere crooked politicians.”

So Sowell is very far from being partial to the Unconstrained vision. He sees it only as dangerous and elitist and as such we have to be mindful of this bias when reading A Conflict of Visions.

It seems that for him the ideal case would be the triumph of the Constrained vision. Of course Sowell doesn’t believe that such an ideal world is going to come to fruition but that would certainly seem to be his preference.

But given that what we have here are two pragmatic maps of reality that have stood the test of time, we must suspect that there are areas where each of them are immensely valuable and so the question becomes how to reconcile these visions so that we can integrate their best parts.

A fruitful starting point is to look at them through a developmental lens. Seen through the lens of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs we can see that they are focused on opposite ends of the human experience.

As every post-apocalyptic movie and tv show knows, when society collapses it’s every man and woman for themselves. Scarcity reveals the “poore, nasty, brutish,” human nature. Yesterday you may have been focused on relationships and success, today you’re just thinking about food, water and warmth.

Civilisation, as Thomas Hobbes argues in his Leviathan, is the dam that holds back these impulses. When people’s basic needs are met, this darkness in human nature is contained and our more pro-social impulses can be emphasised.

The Unconstrained vision on the other hand is focused on the pinnacle of Maslow’s hierarchy: self-actualisation.

For the self-actualising individual whose lower needs are met, money and worldly success are secondary to a higher need. And seen through this lens the philosophies of Marx, Epicurus and Thoreau seem to speak to a deeper truth about humanity. Humans are seen to be fundamentally good creatures that are as in Plato’s allegory, trapped in a cave staring at shadows cast on a wall by a fire rather than out in the real world where the sun shines. We have been alienated from our true natures by the warped landscape of society. There is a sense of a higher truth that most people seem to be missing out on. There is a better world that we want to share with others.

But of course just like the Constrained view, this is a partial truth. Where the Constrained vision are focused on the roots, the Unconstrained see only the flowers and the fruits. But humans are neither entirely good nor bad. As Solzhenitsyn put it “the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.”

The Constrained vision seeks to maintain the stable foundation of the society. It seeks to protect us from ourselves. Society is the dam that restrains the darkness of human nature. And with this darkness stunted, the brighter sides of our nature can develop and grow.

Living in a peaceful and prosperous society, we see people growing more compassionate and wanting to make a world that is founded on these better angels of our nature. And if we are living in a peaceful society and are relatively prosperous it is possible for us to forget about the darkness in human nature. This darkness of human nature is always waiting at the door and when there is a disruption in the order of things it pours into the crevices as we saw with the horrors that followed the French Revolution, the Soviet Revolution and the rise of the Nazis from the First World War and the Wall Street Crash.

This Unconstrained for whatever personal, historical or socioeconomic reasons, are sitting on a higher perch in Maslow’s hierarchy. Like Lao-Tzu they tell us that “Man does not live by bread alone.” But as the history books dotted with Bread Riots would remind us: Without bread man doesn’t live at all and he may even kill other men on the way to his grave.

4 Comments

-

Is it really a binary choice of either/or? So is either vision the better of the two, liberalism (unconstrained) or conservatism (constrained), for they both have their merits and demerits? I’d say that we need to keep a healthy tension between them both. This is akin to Nietzsche’s idea about the Apollonian and Dionysian principles that gave us the ancient Greek culture. The Apollonian principle, being grounded in rationality (constrained), is the structure which contains the energy and vitality of the irrational Dionysian principle (unconstrained).

Therefore, unchallenged conservatism will eventually lead to stagnation and become counterproductive to the onward development of culture. Similarly, unfettered liberalism will inevitably lead to antinomianism and moral chaos. Individual freedom must be channeled through a moral container in order for it to bear the authentic fruits of progress, otherwise the tendency towards degeneracy will result in a regression to a lower level of consciousness.

All of the above can be clearly seen in the parable of the parable of the Prodigal Son from the New Testament who allowed his unconstrained Dionysian (irrational) side to lead him into a life of profligate immorality and spiritual bankruptcy. But having come to his senses he then adopts an Apollonian constrained (rational) perspective which ultimately leads him to a better life of deeper meaning and purpose.

The trick here then is to avoid extremes because nature tends to abhor large imbalances as eventually there always comes an explosive correction that brings about a greater balance. Conservatives can adopt some of the energy and vitality of liberalism because it has a strong moral and traditional structure by which to channel it. Liberalism can likewise flow freely and constructively by working through conservative structures and principles.

Any system of values or ideas must avoid becoming ossified in a rigid tradition otherwise it becomes in danger of losing relevance in a culture that is ever emerging. So in this way we must let ‘the dead bury their own dead’ for life is vibrant and emergent.

In the final analysis, we come to understand that our freedom(s) must be wisely enacted if we are to avoid the extremism at either end of the moral spectrum. It is prudent to avoid becoming stifled by unyielding strict adherence to the cold letter of constraint (morality), and yet live vibrantly via the established trusted structures that morality embodies.

-

It would be wonderful if people could understand that it is the tension between the two – an eternal osculation … that allows humanity to thrive in the balance. If we saw our situation as rowing a canoe down a river (which requires paddling on the left and the right and making adjustments as currents and bends in the river arise) … then we could start appreciating each other and working together to solve problems. This is the antidote to being locked in partisanship and trying to destroy the other in an effort to prove ourselves right (while ultimately destroying ourselves and all good things in the process).

-

[…] those of you who have read the instalment on Thomas Sowell’s A Conflict of Visions this will bring to mind the contrast between the Hobbesian Constrained Vision and the […]

Is it really a binary choice of either/or? So is either vision the better of the two, liberalism (unconstrained) or conservatism (constrained), for they both have their merits and demerits? I’d say that we need to keep a healthy tension between them both. This is akin to Nietzsche’s idea about the Apollonian and Dionysian principles that gave us the ancient Greek culture. The Apollonian principle, being grounded in rationality (constrained), is the structure which contains the energy and vitality of the irrational Dionysian principle (unconstrained).

Therefore, unchallenged conservatism will eventually lead to stagnation and become counterproductive to the onward development of culture. Similarly, unfettered liberalism will inevitably lead to antinomianism and moral chaos. Individual freedom must be channeled through a moral container in order for it to bear the authentic fruits of progress, otherwise the tendency towards degeneracy will result in a regression to a lower level of consciousness.

All of the above can be clearly seen in the parable of the parable of the Prodigal Son from the New Testament who allowed his unconstrained Dionysian (irrational) side to lead him into a life of profligate immorality and spiritual bankruptcy. But having come to his senses he then adopts an Apollonian constrained (rational) perspective which ultimately leads him to a better life of deeper meaning and purpose.

The trick here then is to avoid extremes because nature tends to abhor large imbalances as eventually there always comes an explosive correction that brings about a greater balance. Conservatives can adopt some of the energy and vitality of liberalism because it has a strong moral and traditional structure by which to channel it. Liberalism can likewise flow freely and constructively by working through conservative structures and principles.

Any system of values or ideas must avoid becoming ossified in a rigid tradition otherwise it becomes in danger of losing relevance in a culture that is ever emerging. So in this way we must let ‘the dead bury their own dead’ for life is vibrant and emergent.

In the final analysis, we come to understand that our freedom(s) must be wisely enacted if we are to avoid the extremism at either end of the moral spectrum. It is prudent to avoid becoming stifled by unyielding strict adherence to the cold letter of constraint (morality), and yet live vibrantly via the established trusted structures that morality embodies.

I love it Roy! I’m especially fond of this mapover between the Dionysian and the Apollonian that is brilliant. And I wholeheartedly agree that both are necessary. The tension between them is what keeps thing honest and corrects the exceeses of the other

It would be wonderful if people could understand that it is the tension between the two – an eternal osculation … that allows humanity to thrive in the balance. If we saw our situation as rowing a canoe down a river (which requires paddling on the left and the right and making adjustments as currents and bends in the river arise) … then we could start appreciating each other and working together to solve problems. This is the antidote to being locked in partisanship and trying to destroy the other in an effort to prove ourselves right (while ultimately destroying ourselves and all good things in the process).

[…] those of you who have read the instalment on Thomas Sowell’s A Conflict of Visions this will bring to mind the contrast between the Hobbesian Constrained Vision and the […]