In the wake of the Second World War, it was not only the urban landscape of Europe that was in ruins but the intellectual landscape. In this intellectual crater, several great thinkers debated the blueprint for the future — ‘We were’ as philosopher Simone de Beauvoir put it ‘to provide the postwar era with its ideology’.

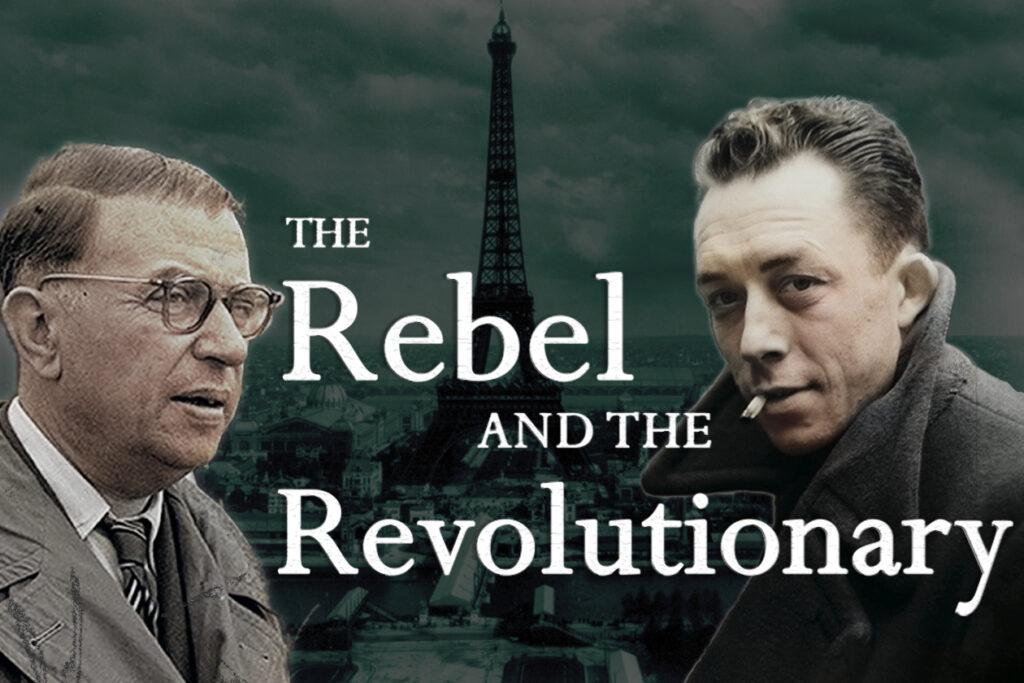

In this postwar landscape, two giants towered above all others: Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. The two men had met in Nazi-Occupied Paris in 1943 and become fast friends. Despite it being their first meeting, they were deeply acquainted with one another — each having reviewed the other’s writings in their journalistic role.

They were the intellectual superstars of their time. Both men went on to win the Nobel Prize for Literature and were cornerstones of French popular culture. Moreover, they were celebrities whose daily movements were considered newsworthy by the papers. And so it is no surprise that after a decade of friendship, the public breakdown of this relationship would be a major cultural event.

This wasn’t just a petty squabble between friends but a philosophical dispute over the course of Europe and the world’s future. Sartre believed that violence was a justifiable means to the great end of Communism; Camus vigorously disagreed.

For those of you who like their knowledge in video format you can check out the video version:

First Encounters

Jean-Paul Sartre first met Albert Camus in June 1943 at the opening of Sartre’s play The Flies. When he was standing in the lobby, according to Simone de Beauvoir,

“a dark-skinned young man came up and introduced himself: it was Albert Camus.” (quote in Aronson 2004)

Camus’s literary star was burning bright at this time — a year earlier, his legendary novel l’Étranger — known in English as the Outsider or the Stranger — was published, and just six months earlier, he had published its philosophical counterpart The Myth of Sisyphus.

“I’m Camus”, he said, and Sartre “found him a most likeable personality.” (Aronson 2004)

The two men hit it off well. So well, in fact, that it made de Beauvoir — the renowned feminist philosopher who was Sartre’s lifelong lover — jealous. De Beauvoir noted that she and Camus were like “two dogs surrounding a bone,” the bone, in this case, being Sartre (Seymour-Jones 2011).

True to French stereotypes, the men talked more about women than about philosophy. They must have made an odd-looking pair, Sartre being as one author has described:

“short, fat, and wall-eyed, ugly by any standard” (Todd 2015)

Camus (image via Wikimedia: Public Domain)

Camus, on the other hand, was often compared to the Hollywood star of Casablanca Humphrey Bogart; he was handsome slim and above-average height.

Just as their appearances were at odds with each other, so too were their backgrounds. Sartre came from an upper-middle-class family and was educated in France’s elite university — the Sorbonne — while Camus was one of the Pieds-Noirs — a derogatory term given to French colonists in Algeria. He was a third-generation colonist on his father’s side and from a poor working-class background. His father died in the First World War just a year after Camus’s birth, and he was raised in a house with his deaf mother, his domineering grandmother, his brother Lucien and his barrel-making uncle Etienne. The two thinkers were cut from very different pieces of France’s cultural tapestry.

Sartre adored Camus’s cheeky side and his appetite for joy, as well as the contrast between his refined books and his saucy jokes (Todd 2015). Camus, for his part, seemed flattered by the invitation to join the Sartre family but remained on the edge of their social circle — always the outsider.

The two became close friends. When interviewed in 1944, Camus said that he had three friends in the literary world, one of which was, of course, Sartre. That same year Sartre asked Camus to direct and star in his new play No Exit. And the following year, Camus offered Sartre the opportunity to travel to America to write a series of articles for his newspaper Combat. When Sartre was there, he wrote about his friend in Vogue magazine:

“In Camus’s sombre, pure works one can already detect the main traits of the French literature of the future. It offers us the promise of a classical literature, without illusions, but full of confidence in the grandeur of humanity; hard but without useless violence; passionate, without restraint […] A literature that tries to portray the metaphysical condition of man while fully participating in the movements of society.”

(quoted in Cohen-Solal 1987: 233–4; Sartre 1981: 1917–21)

Cracks beneath the surface

Everything seemed perfect in the land of the literati. But even at this early stage of the Camus-Sartre friendship, the differences were hiding in plain sight.

Before they had even met, their reviews of each other’s work, while generally laudatory, showed signs of the storms to come. In his review of The Myth of Sisyphus, Sartre placed Camus’s work in the tradition of the French moralistes — a tradition that Sartre was very far from being a fan of.

In a letter to a friend at the time, Camus agreed that “most of his criticisms are fair” but complained of Sartre’s “acid tone”. A few months later, shortly after meeting Sartre for the first time, Camus wrote to the same friend saying that

“In spite of appearances I don’t feel much in common with the work or the man. But seeing those who are against him, we must be with him” (Camus & Grenier 2003: 66, 75; Camus & Grenier 1981: 88, 99).

Even at this height of their friendship, the end was foreshadowed.

The two men had different takes on the existentialist philosophy (with Camus denying his association with the term existentialism entirely and repeatedly), but their real disagreements were political.

Essentially their political disagreements come down to their fundamental disagreement on the relationship between morality and politics. For Camus, politics was subordinated to morality, but in Sartre’s case, it was the opposite.

This point reared many heads in their disagreement, and the two main themes that cropped up were violence and Marxism.

The Rebel Explosions

Liberty leading the people by Eugene Delacroix (image via Wikimedia: Public Domain)

The nascent differences between the philosophers became more and more pronounced as time went on until finally, in 1951, they boiled over with the publication of Camus’s book The Rebel. In this book, Camus’s long cooling attitude towards Communism became an unequivocal disdain. At the heart of the criticism was Camus’s distinction between the rebel and the revolutionary.

Camus — who had anarchist leanings — saw that revolution always implies the establishment of a new government. In The Rebel, he shows how revolution inevitably leads to authoritarian dictatorship and a reinforcement of the power of the state.

Camus argued that the Terror of Robespierre that followed the French Revolution and the Gulags that followed the Soviet revolution were not accidents of history but an inherent pattern of ideological revolutions.

Rebellion is a spontaneous protestation against injustice rather than a planned agenda

For Sartre, such violence was a necessary part of putting the world to rights, but Camus disagreed. In his eyes, the systematic violence ideology committed in the name of revolution was completely unjustifiable. Rather than helping humanity, Camus believed that the revolutionary ideologies such as Marxism and Fascism had added enormously to the suffering of humanity. With the 20th century in the rearview mirror, it’s hard to disagree.

In contrast to the revolutionary, the rebel doesn’t conform to the orthodoxy or some revolutionary ideology but says no to injustice. Rebellion is a spontaneous protestation against injustice rather than a planned agenda like those of the revolutionaries.

Camus sees the rebel more in the politics of reform such as modern trade-union socialism rather than the totalitarian politics of revolutionary ideologies.

The Fall of the Rebel

The Rebel went down like a lead balloon. It irritated every sore nerve between Camus and Sartre, and it sparked a very public disintegration of their relationship. Sartre, who at this point was one of Stalin’s many Western apologists, attacked the book in his publication Les Temps Modernes.

Sartre was a believer in the ends justifying the means, and with his Marxist strain, he believed that — in light of the oppression of the lower classes and this noble end of Communism — violence was not only a necessary evil but “terror becomes revolutionary justice”, and consequently, “the humanization of terror” becomes “possible in principle” (quoted in Foley 2014: 130)

With The Rebel, Camus was making his opposition to this very public. For Camus, the Gulags were not a necessary evil, and they were very far from being just. Where Sartre looked at the cause, Camus looked at the individual humanity. This is why Sartre mocked Camus as one of the moralistes.

After a scathing review of The Rebel in Les Temps Modernes, Camus and Sartre wrote public letters back and forth that marked the end of their friendship. On Sartre’s side, Camus was attacked as a “belle âme” a beautiful soul who prefers to remain pure, uncontaminated by contact with reality; he was said to have misread Hegel, Marx and Sartre; and he was criticised for his readiness to attack the idea of revolution without offering a suitable alternative (quoted in Foley 2014: 112).

As Sartre saw it, in a world weighed down with social injustice, the choice facing the intellectual is either to deny history in the name of metaphysics (another jibe at Camus as a moralist) or to side with the oppressed which could only be done effectively by supporting the Communist Party.

Camus responded that Sartre’s side had wilfully misread The Rebel and, in attacking superficialities about History and Metaphysics, had ignored the central argument of the book about the implications of authoritarian socialism. The Les Temps Modernes responses also completely ignored Camus’s lengthy discussions about revolutionary violence and the question of legitimate political violence.

A little crook from Algiers

The Rebel’s publication marked the end of Sartre and Camus’s friendship. When Camus died in 1960 in a car crash at the age of 44, Sartre wrote an oft-quoted eulogy for his old friend which on the surface of it sounds quite nice but brings up the same subtle jabs. Sartre says he admired Camus’s:

“stubborn humanism, strict and pure, austere and sensual, [which] delivered uncertain combat against the massive and deformed events of the day.” (Sartre 1962)

He also observes that:

“by the unexpectedness of his refusals, he reaffirmed, at the heart of our era, against the Machiavellians, against the golden calf of realism, the existence of the moral act.” (Sartre 1962)

As profound and generous as these words seem, they are laced with Sartre’s disdain for moralism, and in a later letter to a friend, he felt he was too generous:

“There is a little falsehood in the obituary I wrote about Camus…He wasn’t a boy who was made for all that he tried to do, he should have been a little crook from Algiers, a very funny one, who might have managed to write a few books, but mostly remain a crook.” (quoted in Todd 2015)

Sartre, for all his hatred of the class system, still felt himself superior to Camus by virtue of his higher education and refinement. As a Marxist, Sartre had an ostensible love for the lower classes. But his sense that a man who rose from this reality to become a towering intellectual “should have been a little crook from Algiers” tells a different story. It brings to mind George Orwell words in The Road to Wigan Pier:

Sometimes I look at a Socialist — the intellectual, tract-writing type of Socialist, with his pullover, his fuzzy hair, and his Marxian quotation — and wonder what the devil his motive really is. It is often difficult to believe that it is a love of anybody, especially of the working class, from whom he is of all people the furthest removed.

The truth is that, to many people calling themselves Socialists, revolution does not mean a movement of the masses with which they hope to associate themselves; it means a set of reforms which ‘we’, the clever ones, are going to impose upon ‘them’, the Lower Orders. On the other hand, it would be a mistake to regard the book-trained Socialist as a bloodless creature entirely incapable of emotion. Though seldom giving much evidence of affection for the exploited, he is perfectly capable of displaying hatred — a sort of queer, theoretical, in vacua hatred — against the exploiters. Hence the grand old Socialist sport of denouncing the bourgeoisie. It is strange how easily almost any Socialist writer can lash himself into frenzies of rage against the class to which, by birth or by adoption, he himself invariably belongs. (Orwell 2021:123)

Camus crowning Princess Lucia of Sweden (image via Wikimedia: Public Domain)

Despite Sartre’s supercilious sneers, Camus appears to be having the last laugh. Sartre’s star has been long on the wane and certain accusations of sexual depravity have helped to speed this decline.

Camus’s star, on the other hand, seems to be on the rise. As time has passed, his true class has come to shine ever brighter. He was a man who lived his philosophy, who not only talked the talk but walked the walk. He rose from poverty in one of France’s colonies to the heights of the intellectual peaks becoming the second youngest Nobel Laureate for Literature.

He was willing to be true to his beliefs, whether it put himself or his career in mortal danger. As an outspoken advocate for peace and the rights of the native Algerians, his newspaper was shut down in 1939, and he was forced into exile, unable to find work in his home country.

In Paris, he became an active member of the French Resistance and, though he never held a gun, he risked his life for a noble cause. And then he spoke out against revolutionary violence. He was “disgusted by the hate which submerges us today” and felt that the “only values worth defending” were “love and the mind.” Not bad from a man who should have been “a little crook from Algiers.” (quoted in Todd 2015)

Sources:

- Aronson, R., 2004. Camus and Sartre: The story of a friendship and the quarrel that ended it. University of Chicago Press.

- Camus, A. and Grenier, J., 2003. Correspondence, 1932-1960. U of Nebraska Press.

- Cohen-Salal, A., 1987. Sartre: A Life, tr. A. Cancogni, ed. N. MacAfee.

- Foley, J., 2014. Albert Camus: From the absurd to revolt. Routledge.

- Orwell, G., 2021. The road to Wigan pier. Oxford University Press.

- Sartre, J.P., 1962. Tribute to Albert Camus. Camus: A Collection of Critical Essays, pp.173-175.

- Seymour-Jones, C., 2011. A dangerous liaison. Random House.

- Todd, O., 2015. Albert Camus: A Life. Random House.

6 Comments

Leave A Comment

In the wake of the Second World War, it was not only the urban landscape of Europe that was in ruins but the intellectual landscape. In this intellectual crater, several great thinkers debated the blueprint for the future — ‘We were’ as philosopher Simone de Beauvoir put it ‘to provide the postwar era with its ideology’.

In this postwar landscape, two giants towered above all others: Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. The two men had met in Nazi-Occupied Paris in 1943 and become fast friends. Despite it being their first meeting, they were deeply acquainted with one another — each having reviewed the other’s writings in their journalistic role.

They were the intellectual superstars of their time. Both men went on to win the Nobel Prize for Literature and were cornerstones of French popular culture. Moreover, they were celebrities whose daily movements were considered newsworthy by the papers. And so it is no surprise that after a decade of friendship, the public breakdown of this relationship would be a major cultural event.

This wasn’t just a petty squabble between friends but a philosophical dispute over the course of Europe and the world’s future. Sartre believed that violence was a justifiable means to the great end of Communism; Camus vigorously disagreed.

For those of you who like their knowledge in video format you can check out the video version:

First Encounters

Jean-Paul Sartre first met Albert Camus in June 1943 at the opening of Sartre’s play The Flies. When he was standing in the lobby, according to Simone de Beauvoir,

“a dark-skinned young man came up and introduced himself: it was Albert Camus.” (quote in Aronson 2004)

Camus’s literary star was burning bright at this time — a year earlier, his legendary novel l’Étranger — known in English as the Outsider or the Stranger — was published, and just six months earlier, he had published its philosophical counterpart The Myth of Sisyphus.

“I’m Camus”, he said, and Sartre “found him a most likeable personality.” (Aronson 2004)

The two men hit it off well. So well, in fact, that it made de Beauvoir — the renowned feminist philosopher who was Sartre’s lifelong lover — jealous. De Beauvoir noted that she and Camus were like “two dogs surrounding a bone,” the bone, in this case, being Sartre (Seymour-Jones 2011).

True to French stereotypes, the men talked more about women than about philosophy. They must have made an odd-looking pair, Sartre being as one author has described:

“short, fat, and wall-eyed, ugly by any standard” (Todd 2015)

Camus (image via Wikimedia: Public Domain)

Camus, on the other hand, was often compared to the Hollywood star of Casablanca Humphrey Bogart; he was handsome slim and above-average height.

Just as their appearances were at odds with each other, so too were their backgrounds. Sartre came from an upper-middle-class family and was educated in France’s elite university — the Sorbonne — while Camus was one of the Pieds-Noirs — a derogatory term given to French colonists in Algeria. He was a third-generation colonist on his father’s side and from a poor working-class background. His father died in the First World War just a year after Camus’s birth, and he was raised in a house with his deaf mother, his domineering grandmother, his brother Lucien and his barrel-making uncle Etienne. The two thinkers were cut from very different pieces of France’s cultural tapestry.

Sartre adored Camus’s cheeky side and his appetite for joy, as well as the contrast between his refined books and his saucy jokes (Todd 2015). Camus, for his part, seemed flattered by the invitation to join the Sartre family but remained on the edge of their social circle — always the outsider.

The two became close friends. When interviewed in 1944, Camus said that he had three friends in the literary world, one of which was, of course, Sartre. That same year Sartre asked Camus to direct and star in his new play No Exit. And the following year, Camus offered Sartre the opportunity to travel to America to write a series of articles for his newspaper Combat. When Sartre was there, he wrote about his friend in Vogue magazine:

“In Camus’s sombre, pure works one can already detect the main traits of the French literature of the future. It offers us the promise of a classical literature, without illusions, but full of confidence in the grandeur of humanity; hard but without useless violence; passionate, without restraint […] A literature that tries to portray the metaphysical condition of man while fully participating in the movements of society.”

(quoted in Cohen-Solal 1987: 233–4; Sartre 1981: 1917–21)

Cracks beneath the surface

Everything seemed perfect in the land of the literati. But even at this early stage of the Camus-Sartre friendship, the differences were hiding in plain sight.

Before they had even met, their reviews of each other’s work, while generally laudatory, showed signs of the storms to come. In his review of The Myth of Sisyphus, Sartre placed Camus’s work in the tradition of the French moralistes — a tradition that Sartre was very far from being a fan of.

In a letter to a friend at the time, Camus agreed that “most of his criticisms are fair” but complained of Sartre’s “acid tone”. A few months later, shortly after meeting Sartre for the first time, Camus wrote to the same friend saying that

“In spite of appearances I don’t feel much in common with the work or the man. But seeing those who are against him, we must be with him” (Camus & Grenier 2003: 66, 75; Camus & Grenier 1981: 88, 99).

Even at this height of their friendship, the end was foreshadowed.

The two men had different takes on the existentialist philosophy (with Camus denying his association with the term existentialism entirely and repeatedly), but their real disagreements were political.

Essentially their political disagreements come down to their fundamental disagreement on the relationship between morality and politics. For Camus, politics was subordinated to morality, but in Sartre’s case, it was the opposite.

This point reared many heads in their disagreement, and the two main themes that cropped up were violence and Marxism.

The Rebel Explosions

Liberty leading the people by Eugene Delacroix (image via Wikimedia: Public Domain)

The nascent differences between the philosophers became more and more pronounced as time went on until finally, in 1951, they boiled over with the publication of Camus’s book The Rebel. In this book, Camus’s long cooling attitude towards Communism became an unequivocal disdain. At the heart of the criticism was Camus’s distinction between the rebel and the revolutionary.

Camus — who had anarchist leanings — saw that revolution always implies the establishment of a new government. In The Rebel, he shows how revolution inevitably leads to authoritarian dictatorship and a reinforcement of the power of the state.

Camus argued that the Terror of Robespierre that followed the French Revolution and the Gulags that followed the Soviet revolution were not accidents of history but an inherent pattern of ideological revolutions.

Rebellion is a spontaneous protestation against injustice rather than a planned agenda

For Sartre, such violence was a necessary part of putting the world to rights, but Camus disagreed. In his eyes, the systematic violence ideology committed in the name of revolution was completely unjustifiable. Rather than helping humanity, Camus believed that the revolutionary ideologies such as Marxism and Fascism had added enormously to the suffering of humanity. With the 20th century in the rearview mirror, it’s hard to disagree.

In contrast to the revolutionary, the rebel doesn’t conform to the orthodoxy or some revolutionary ideology but says no to injustice. Rebellion is a spontaneous protestation against injustice rather than a planned agenda like those of the revolutionaries.

Camus sees the rebel more in the politics of reform such as modern trade-union socialism rather than the totalitarian politics of revolutionary ideologies.

The Fall of the Rebel

The Rebel went down like a lead balloon. It irritated every sore nerve between Camus and Sartre, and it sparked a very public disintegration of their relationship. Sartre, who at this point was one of Stalin’s many Western apologists, attacked the book in his publication Les Temps Modernes.

Sartre was a believer in the ends justifying the means, and with his Marxist strain, he believed that — in light of the oppression of the lower classes and this noble end of Communism — violence was not only a necessary evil but “terror becomes revolutionary justice”, and consequently, “the humanization of terror” becomes “possible in principle” (quoted in Foley 2014: 130)

With The Rebel, Camus was making his opposition to this very public. For Camus, the Gulags were not a necessary evil, and they were very far from being just. Where Sartre looked at the cause, Camus looked at the individual humanity. This is why Sartre mocked Camus as one of the moralistes.

After a scathing review of The Rebel in Les Temps Modernes, Camus and Sartre wrote public letters back and forth that marked the end of their friendship. On Sartre’s side, Camus was attacked as a “belle âme” a beautiful soul who prefers to remain pure, uncontaminated by contact with reality; he was said to have misread Hegel, Marx and Sartre; and he was criticised for his readiness to attack the idea of revolution without offering a suitable alternative (quoted in Foley 2014: 112).

As Sartre saw it, in a world weighed down with social injustice, the choice facing the intellectual is either to deny history in the name of metaphysics (another jibe at Camus as a moralist) or to side with the oppressed which could only be done effectively by supporting the Communist Party.

Camus responded that Sartre’s side had wilfully misread The Rebel and, in attacking superficialities about History and Metaphysics, had ignored the central argument of the book about the implications of authoritarian socialism. The Les Temps Modernes responses also completely ignored Camus’s lengthy discussions about revolutionary violence and the question of legitimate political violence.

A little crook from Algiers

The Rebel’s publication marked the end of Sartre and Camus’s friendship. When Camus died in 1960 in a car crash at the age of 44, Sartre wrote an oft-quoted eulogy for his old friend which on the surface of it sounds quite nice but brings up the same subtle jabs. Sartre says he admired Camus’s:

“stubborn humanism, strict and pure, austere and sensual, [which] delivered uncertain combat against the massive and deformed events of the day.” (Sartre 1962)

He also observes that:

“by the unexpectedness of his refusals, he reaffirmed, at the heart of our era, against the Machiavellians, against the golden calf of realism, the existence of the moral act.” (Sartre 1962)

As profound and generous as these words seem, they are laced with Sartre’s disdain for moralism, and in a later letter to a friend, he felt he was too generous:

“There is a little falsehood in the obituary I wrote about Camus…He wasn’t a boy who was made for all that he tried to do, he should have been a little crook from Algiers, a very funny one, who might have managed to write a few books, but mostly remain a crook.” (quoted in Todd 2015)

Sartre, for all his hatred of the class system, still felt himself superior to Camus by virtue of his higher education and refinement. As a Marxist, Sartre had an ostensible love for the lower classes. But his sense that a man who rose from this reality to become a towering intellectual “should have been a little crook from Algiers” tells a different story. It brings to mind George Orwell words in The Road to Wigan Pier:

Sometimes I look at a Socialist — the intellectual, tract-writing type of Socialist, with his pullover, his fuzzy hair, and his Marxian quotation — and wonder what the devil his motive really is. It is often difficult to believe that it is a love of anybody, especially of the working class, from whom he is of all people the furthest removed.

The truth is that, to many people calling themselves Socialists, revolution does not mean a movement of the masses with which they hope to associate themselves; it means a set of reforms which ‘we’, the clever ones, are going to impose upon ‘them’, the Lower Orders. On the other hand, it would be a mistake to regard the book-trained Socialist as a bloodless creature entirely incapable of emotion. Though seldom giving much evidence of affection for the exploited, he is perfectly capable of displaying hatred — a sort of queer, theoretical, in vacua hatred — against the exploiters. Hence the grand old Socialist sport of denouncing the bourgeoisie. It is strange how easily almost any Socialist writer can lash himself into frenzies of rage against the class to which, by birth or by adoption, he himself invariably belongs. (Orwell 2021:123)

Camus crowning Princess Lucia of Sweden (image via Wikimedia: Public Domain)

Despite Sartre’s supercilious sneers, Camus appears to be having the last laugh. Sartre’s star has been long on the wane and certain accusations of sexual depravity have helped to speed this decline.

Camus’s star, on the other hand, seems to be on the rise. As time has passed, his true class has come to shine ever brighter. He was a man who lived his philosophy, who not only talked the talk but walked the walk. He rose from poverty in one of France’s colonies to the heights of the intellectual peaks becoming the second youngest Nobel Laureate for Literature.

He was willing to be true to his beliefs, whether it put himself or his career in mortal danger. As an outspoken advocate for peace and the rights of the native Algerians, his newspaper was shut down in 1939, and he was forced into exile, unable to find work in his home country.

In Paris, he became an active member of the French Resistance and, though he never held a gun, he risked his life for a noble cause. And then he spoke out against revolutionary violence. He was “disgusted by the hate which submerges us today” and felt that the “only values worth defending” were “love and the mind.” Not bad from a man who should have been “a little crook from Algiers.” (quoted in Todd 2015)

Sources:

- Aronson, R., 2004. Camus and Sartre: The story of a friendship and the quarrel that ended it. University of Chicago Press.

- Camus, A. and Grenier, J., 2003. Correspondence, 1932-1960. U of Nebraska Press.

- Cohen-Salal, A., 1987. Sartre: A Life, tr. A. Cancogni, ed. N. MacAfee.

- Foley, J., 2014. Albert Camus: From the absurd to revolt. Routledge.

- Orwell, G., 2021. The road to Wigan pier. Oxford University Press.

- Sartre, J.P., 1962. Tribute to Albert Camus. Camus: A Collection of Critical Essays, pp.173-175.

- Seymour-Jones, C., 2011. A dangerous liaison. Random House.

- Todd, O., 2015. Albert Camus: A Life. Random House.

6 Comments

-

[…] centre of gravity moved West from Germany to France and there it became a foundational aspect of Jean-Paul Sartre’s Existentialist philosophy and the philosophy of Maurice […]

-

[…] than one passing reference to Lyotard, another to Sartre and a few to Lacan, Peterson never really discusses any other philosophers of this era in any […]

-

[…] of Existentialism”. But unlike many of his Existentialist peers from Nietzsche to Camus, Kierkegaard was not an atheist. He was a devout […]

-

[…] bridge between so many of the topics that fascinate me — from why I love the Existentialism of Camus and the philosophy of the Ancients (whether that’s Heraclitus or the Stoics) to why I […]

-

As an undergrad in the early 1980s, I took a class on Sartre from a Benedictine Monk named Fr, Rene Moran at St. John’s University in Central Minnesota. Fr. Rene was also the founder of the Peace Studies Program at SJU. Your video not only provided me with the critical context I had lacked for over 40 years–Sartre’s acceptance of violence and Camus’s adherence to negotiation and non-violence–but also shed light on why Fr. Rene, the peace advocate, chose to teach a course based upon Being and Nothingness and existential philosophy. I now see how he encouraged us to think critically about social justice work. The red thread that weaves your entire series concerns LIVING your PHILOSOPHY, which Sartre failed to do, choosing to stay. Instead, comfortable in his intellectual ivory tower.

Leave A Comment

In the wake of the Second World War, it was not only the urban landscape of Europe that was in ruins but the intellectual landscape. In this intellectual crater, several great thinkers debated the blueprint for the future — ‘We were’ as philosopher Simone de Beauvoir put it ‘to provide the postwar era with its ideology’.

In this postwar landscape, two giants towered above all others: Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. The two men had met in Nazi-Occupied Paris in 1943 and become fast friends. Despite it being their first meeting, they were deeply acquainted with one another — each having reviewed the other’s writings in their journalistic role.

They were the intellectual superstars of their time. Both men went on to win the Nobel Prize for Literature and were cornerstones of French popular culture. Moreover, they were celebrities whose daily movements were considered newsworthy by the papers. And so it is no surprise that after a decade of friendship, the public breakdown of this relationship would be a major cultural event.

This wasn’t just a petty squabble between friends but a philosophical dispute over the course of Europe and the world’s future. Sartre believed that violence was a justifiable means to the great end of Communism; Camus vigorously disagreed.

For those of you who like their knowledge in video format you can check out the video version:

First Encounters

Jean-Paul Sartre first met Albert Camus in June 1943 at the opening of Sartre’s play The Flies. When he was standing in the lobby, according to Simone de Beauvoir,

“a dark-skinned young man came up and introduced himself: it was Albert Camus.” (quote in Aronson 2004)

Camus’s literary star was burning bright at this time — a year earlier, his legendary novel l’Étranger — known in English as the Outsider or the Stranger — was published, and just six months earlier, he had published its philosophical counterpart The Myth of Sisyphus.

“I’m Camus”, he said, and Sartre “found him a most likeable personality.” (Aronson 2004)

The two men hit it off well. So well, in fact, that it made de Beauvoir — the renowned feminist philosopher who was Sartre’s lifelong lover — jealous. De Beauvoir noted that she and Camus were like “two dogs surrounding a bone,” the bone, in this case, being Sartre (Seymour-Jones 2011).

True to French stereotypes, the men talked more about women than about philosophy. They must have made an odd-looking pair, Sartre being as one author has described:

“short, fat, and wall-eyed, ugly by any standard” (Todd 2015)

Camus (image via Wikimedia: Public Domain)

Camus, on the other hand, was often compared to the Hollywood star of Casablanca Humphrey Bogart; he was handsome slim and above-average height.

Just as their appearances were at odds with each other, so too were their backgrounds. Sartre came from an upper-middle-class family and was educated in France’s elite university — the Sorbonne — while Camus was one of the Pieds-Noirs — a derogatory term given to French colonists in Algeria. He was a third-generation colonist on his father’s side and from a poor working-class background. His father died in the First World War just a year after Camus’s birth, and he was raised in a house with his deaf mother, his domineering grandmother, his brother Lucien and his barrel-making uncle Etienne. The two thinkers were cut from very different pieces of France’s cultural tapestry.

Sartre adored Camus’s cheeky side and his appetite for joy, as well as the contrast between his refined books and his saucy jokes (Todd 2015). Camus, for his part, seemed flattered by the invitation to join the Sartre family but remained on the edge of their social circle — always the outsider.

The two became close friends. When interviewed in 1944, Camus said that he had three friends in the literary world, one of which was, of course, Sartre. That same year Sartre asked Camus to direct and star in his new play No Exit. And the following year, Camus offered Sartre the opportunity to travel to America to write a series of articles for his newspaper Combat. When Sartre was there, he wrote about his friend in Vogue magazine:

“In Camus’s sombre, pure works one can already detect the main traits of the French literature of the future. It offers us the promise of a classical literature, without illusions, but full of confidence in the grandeur of humanity; hard but without useless violence; passionate, without restraint […] A literature that tries to portray the metaphysical condition of man while fully participating in the movements of society.”

(quoted in Cohen-Solal 1987: 233–4; Sartre 1981: 1917–21)

Cracks beneath the surface

Everything seemed perfect in the land of the literati. But even at this early stage of the Camus-Sartre friendship, the differences were hiding in plain sight.

Before they had even met, their reviews of each other’s work, while generally laudatory, showed signs of the storms to come. In his review of The Myth of Sisyphus, Sartre placed Camus’s work in the tradition of the French moralistes — a tradition that Sartre was very far from being a fan of.

In a letter to a friend at the time, Camus agreed that “most of his criticisms are fair” but complained of Sartre’s “acid tone”. A few months later, shortly after meeting Sartre for the first time, Camus wrote to the same friend saying that

“In spite of appearances I don’t feel much in common with the work or the man. But seeing those who are against him, we must be with him” (Camus & Grenier 2003: 66, 75; Camus & Grenier 1981: 88, 99).

Even at this height of their friendship, the end was foreshadowed.

The two men had different takes on the existentialist philosophy (with Camus denying his association with the term existentialism entirely and repeatedly), but their real disagreements were political.

Essentially their political disagreements come down to their fundamental disagreement on the relationship between morality and politics. For Camus, politics was subordinated to morality, but in Sartre’s case, it was the opposite.

This point reared many heads in their disagreement, and the two main themes that cropped up were violence and Marxism.

The Rebel Explosions

Liberty leading the people by Eugene Delacroix (image via Wikimedia: Public Domain)

The nascent differences between the philosophers became more and more pronounced as time went on until finally, in 1951, they boiled over with the publication of Camus’s book The Rebel. In this book, Camus’s long cooling attitude towards Communism became an unequivocal disdain. At the heart of the criticism was Camus’s distinction between the rebel and the revolutionary.

Camus — who had anarchist leanings — saw that revolution always implies the establishment of a new government. In The Rebel, he shows how revolution inevitably leads to authoritarian dictatorship and a reinforcement of the power of the state.

Camus argued that the Terror of Robespierre that followed the French Revolution and the Gulags that followed the Soviet revolution were not accidents of history but an inherent pattern of ideological revolutions.

Rebellion is a spontaneous protestation against injustice rather than a planned agenda

For Sartre, such violence was a necessary part of putting the world to rights, but Camus disagreed. In his eyes, the systematic violence ideology committed in the name of revolution was completely unjustifiable. Rather than helping humanity, Camus believed that the revolutionary ideologies such as Marxism and Fascism had added enormously to the suffering of humanity. With the 20th century in the rearview mirror, it’s hard to disagree.

In contrast to the revolutionary, the rebel doesn’t conform to the orthodoxy or some revolutionary ideology but says no to injustice. Rebellion is a spontaneous protestation against injustice rather than a planned agenda like those of the revolutionaries.

Camus sees the rebel more in the politics of reform such as modern trade-union socialism rather than the totalitarian politics of revolutionary ideologies.

The Fall of the Rebel

The Rebel went down like a lead balloon. It irritated every sore nerve between Camus and Sartre, and it sparked a very public disintegration of their relationship. Sartre, who at this point was one of Stalin’s many Western apologists, attacked the book in his publication Les Temps Modernes.

Sartre was a believer in the ends justifying the means, and with his Marxist strain, he believed that — in light of the oppression of the lower classes and this noble end of Communism — violence was not only a necessary evil but “terror becomes revolutionary justice”, and consequently, “the humanization of terror” becomes “possible in principle” (quoted in Foley 2014: 130)

With The Rebel, Camus was making his opposition to this very public. For Camus, the Gulags were not a necessary evil, and they were very far from being just. Where Sartre looked at the cause, Camus looked at the individual humanity. This is why Sartre mocked Camus as one of the moralistes.

After a scathing review of The Rebel in Les Temps Modernes, Camus and Sartre wrote public letters back and forth that marked the end of their friendship. On Sartre’s side, Camus was attacked as a “belle âme” a beautiful soul who prefers to remain pure, uncontaminated by contact with reality; he was said to have misread Hegel, Marx and Sartre; and he was criticised for his readiness to attack the idea of revolution without offering a suitable alternative (quoted in Foley 2014: 112).

As Sartre saw it, in a world weighed down with social injustice, the choice facing the intellectual is either to deny history in the name of metaphysics (another jibe at Camus as a moralist) or to side with the oppressed which could only be done effectively by supporting the Communist Party.

Camus responded that Sartre’s side had wilfully misread The Rebel and, in attacking superficialities about History and Metaphysics, had ignored the central argument of the book about the implications of authoritarian socialism. The Les Temps Modernes responses also completely ignored Camus’s lengthy discussions about revolutionary violence and the question of legitimate political violence.

A little crook from Algiers

The Rebel’s publication marked the end of Sartre and Camus’s friendship. When Camus died in 1960 in a car crash at the age of 44, Sartre wrote an oft-quoted eulogy for his old friend which on the surface of it sounds quite nice but brings up the same subtle jabs. Sartre says he admired Camus’s:

“stubborn humanism, strict and pure, austere and sensual, [which] delivered uncertain combat against the massive and deformed events of the day.” (Sartre 1962)

He also observes that:

“by the unexpectedness of his refusals, he reaffirmed, at the heart of our era, against the Machiavellians, against the golden calf of realism, the existence of the moral act.” (Sartre 1962)

As profound and generous as these words seem, they are laced with Sartre’s disdain for moralism, and in a later letter to a friend, he felt he was too generous:

“There is a little falsehood in the obituary I wrote about Camus…He wasn’t a boy who was made for all that he tried to do, he should have been a little crook from Algiers, a very funny one, who might have managed to write a few books, but mostly remain a crook.” (quoted in Todd 2015)

Sartre, for all his hatred of the class system, still felt himself superior to Camus by virtue of his higher education and refinement. As a Marxist, Sartre had an ostensible love for the lower classes. But his sense that a man who rose from this reality to become a towering intellectual “should have been a little crook from Algiers” tells a different story. It brings to mind George Orwell words in The Road to Wigan Pier:

Sometimes I look at a Socialist — the intellectual, tract-writing type of Socialist, with his pullover, his fuzzy hair, and his Marxian quotation — and wonder what the devil his motive really is. It is often difficult to believe that it is a love of anybody, especially of the working class, from whom he is of all people the furthest removed.

The truth is that, to many people calling themselves Socialists, revolution does not mean a movement of the masses with which they hope to associate themselves; it means a set of reforms which ‘we’, the clever ones, are going to impose upon ‘them’, the Lower Orders. On the other hand, it would be a mistake to regard the book-trained Socialist as a bloodless creature entirely incapable of emotion. Though seldom giving much evidence of affection for the exploited, he is perfectly capable of displaying hatred — a sort of queer, theoretical, in vacua hatred — against the exploiters. Hence the grand old Socialist sport of denouncing the bourgeoisie. It is strange how easily almost any Socialist writer can lash himself into frenzies of rage against the class to which, by birth or by adoption, he himself invariably belongs. (Orwell 2021:123)

Camus crowning Princess Lucia of Sweden (image via Wikimedia: Public Domain)

Despite Sartre’s supercilious sneers, Camus appears to be having the last laugh. Sartre’s star has been long on the wane and certain accusations of sexual depravity have helped to speed this decline.

Camus’s star, on the other hand, seems to be on the rise. As time has passed, his true class has come to shine ever brighter. He was a man who lived his philosophy, who not only talked the talk but walked the walk. He rose from poverty in one of France’s colonies to the heights of the intellectual peaks becoming the second youngest Nobel Laureate for Literature.

He was willing to be true to his beliefs, whether it put himself or his career in mortal danger. As an outspoken advocate for peace and the rights of the native Algerians, his newspaper was shut down in 1939, and he was forced into exile, unable to find work in his home country.

In Paris, he became an active member of the French Resistance and, though he never held a gun, he risked his life for a noble cause. And then he spoke out against revolutionary violence. He was “disgusted by the hate which submerges us today” and felt that the “only values worth defending” were “love and the mind.” Not bad from a man who should have been “a little crook from Algiers.” (quoted in Todd 2015)

Sources:

- Aronson, R., 2004. Camus and Sartre: The story of a friendship and the quarrel that ended it. University of Chicago Press.

- Camus, A. and Grenier, J., 2003. Correspondence, 1932-1960. U of Nebraska Press.

- Cohen-Salal, A., 1987. Sartre: A Life, tr. A. Cancogni, ed. N. MacAfee.

- Foley, J., 2014. Albert Camus: From the absurd to revolt. Routledge.

- Orwell, G., 2021. The road to Wigan pier. Oxford University Press.

- Sartre, J.P., 1962. Tribute to Albert Camus. Camus: A Collection of Critical Essays, pp.173-175.

- Seymour-Jones, C., 2011. A dangerous liaison. Random House.

- Todd, O., 2015. Albert Camus: A Life. Random House.

6 Comments

-

[…] centre of gravity moved West from Germany to France and there it became a foundational aspect of Jean-Paul Sartre’s Existentialist philosophy and the philosophy of Maurice […]

-

[…] than one passing reference to Lyotard, another to Sartre and a few to Lacan, Peterson never really discusses any other philosophers of this era in any […]

-

[…] of Existentialism”. But unlike many of his Existentialist peers from Nietzsche to Camus, Kierkegaard was not an atheist. He was a devout […]

-

[…] bridge between so many of the topics that fascinate me — from why I love the Existentialism of Camus and the philosophy of the Ancients (whether that’s Heraclitus or the Stoics) to why I […]

-

As an undergrad in the early 1980s, I took a class on Sartre from a Benedictine Monk named Fr, Rene Moran at St. John’s University in Central Minnesota. Fr. Rene was also the founder of the Peace Studies Program at SJU. Your video not only provided me with the critical context I had lacked for over 40 years–Sartre’s acceptance of violence and Camus’s adherence to negotiation and non-violence–but also shed light on why Fr. Rene, the peace advocate, chose to teach a course based upon Being and Nothingness and existential philosophy. I now see how he encouraged us to think critically about social justice work. The red thread that weaves your entire series concerns LIVING your PHILOSOPHY, which Sartre failed to do, choosing to stay. Instead, comfortable in his intellectual ivory tower.

[…] centre of gravity moved West from Germany to France and there it became a foundational aspect of Jean-Paul Sartre’s Existentialist philosophy and the philosophy of Maurice […]

[…] than one passing reference to Lyotard, another to Sartre and a few to Lacan, Peterson never really discusses any other philosophers of this era in any […]

[…] of Existentialism”. But unlike many of his Existentialist peers from Nietzsche to Camus, Kierkegaard was not an atheist. He was a devout […]

[…] https://www.thelivingphilosophy.com/camus-vs-sartre/ […]

[…] bridge between so many of the topics that fascinate me — from why I love the Existentialism of Camus and the philosophy of the Ancients (whether that’s Heraclitus or the Stoics) to why I […]

As an undergrad in the early 1980s, I took a class on Sartre from a Benedictine Monk named Fr, Rene Moran at St. John’s University in Central Minnesota. Fr. Rene was also the founder of the Peace Studies Program at SJU. Your video not only provided me with the critical context I had lacked for over 40 years–Sartre’s acceptance of violence and Camus’s adherence to negotiation and non-violence–but also shed light on why Fr. Rene, the peace advocate, chose to teach a course based upon Being and Nothingness and existential philosophy. I now see how he encouraged us to think critically about social justice work. The red thread that weaves your entire series concerns LIVING your PHILOSOPHY, which Sartre failed to do, choosing to stay. Instead, comfortable in his intellectual ivory tower.